The Woolen Industry of the Midwest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consumption on the Woolen System and Worsted Combing

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SNHU Academic Archive Consumption on the Woolen System and Worsted Combing: 2002 Issued June 2003 Summary MQ313D(02)-5 Current Industrial Reports Current data are released electronically on Internet and STAT-USA by subscription. The Internet for all individual surveys as they become avail- address is: www.stat-usa.gov/. Follow the able. Use: http://www.census.gov/mcd/. prompts to register. Also, you may call Individual reports can be accessed by choosing 202-482-1986 or 1-800-STAT-USA, for "Current Industrial Reports (CIR)," clicking on further information. "CIRs by Subsector;" then choose the survey of interest. Follow the menu to view the PDF file or For general CIR information, explanation of to download the worksheet file (WK format) to general terms and historical note, see the your personal computer. appendix. These data are also available on Internet through the U.S. Department of Commerce Address inquiries concerning these data to Consumer Goods Industries Branch, Manufacturing and Construction Division (MCD), Washington, DC 20233- 6900, or call Robert Lee, 301-763-4637. For mail or fax copies of this publication, please contact the Information Services Center, MCD, Washington, DC 20233-6900, or call 301-763-4673. U S C E N S U S B U R E A U U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration Helping You Make Informed Decisions U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Table 1. Summary of Fibers Consumed in Woolen Spinning and Worsted Combing: 1998 to 2002 [Thousands -

Spinning Machinery

panty portion of support pantyhose. Future development HFP of Heberlein Maschinenfabrik AG had been develop- of air covering machine might be focused on the improve- ed as an interlacer and has been put to practical use. Since ment of nozzle in order to get even entanglement appro- it is effective for air covering, it has been supplied to air priate strength and less air consumption. covering machines of ICBT International land Guidici. In addition, a new type nozzle, called "BCF-JET", used for 7. Other Related Machineries and Equipments thick carpet yarn of 1,000 - 12,000 dtex was also ex- hibited. The shape of a slit of V-Jet exhibited by Fiber- An exhibition of machinery and equipments related to guide Limited is featured by easy processing of yarn, and manufacturing machine for chemical and synthetic fiber less accumulation of dirt. It has been put to practical use varied widely from spinnerets to measuring instrument. for air covering as well as non-sizing texturing and air Such as suction guns, false-twisting friction disk unit, mixing texturing. magnet spindles, air jet nozzles, yarn guides, rubber apron/roller etc. and measuring instruments. (3) Measuring Instruments for Filament Yarn Some exhibits are briefly summarized as follows: There were many other exhibits from manufacturers of testing instruments introducing a variety of measuring (1) Suction Guns instruments, on-line measurements, quality control An air sucker is generally used for yarn suction in systems according to the importance of quality control package mounting onto take-up winders and other similar complying with diversity of end-uses and high quality. -

Spininnovation

No. 24 07.2008 € INNOVATION 5,– SPIN THE MAGAZINE FOR SPINNING MILLS COREflex® – Core Yarn Attachment for Ring Spinning Machines ACP Quality Package Premium Parts – News HP-GX 5010 New Top Weighting Arms Mill Reports: – Nahar, India – Danmao, China Berkol – Part of Bräcker Wilhelm Stahlecker GmbH CONTENTS Editorial 3 COREflex® – Spinning Soft Core Yarn on Ring and Compact Spinning Machines 5 Yarn Quality Improved by ACP Quality Package 9 Premium Parts – News – Metal Washer for Magnetic Navals – CR-Coating for B 174 and B 20 SOLIDRINGS – ProFiL®Navels 15 The Theory of Compacting 19 BERKOL® – Becomes Part of Bräcker AG, Switzerland 21 NAHAR – A Saga from Farm to Fashion 23 Experience with EliTe® and EliTwist®CompactSet – A Practical Assessment , Nahar Industries, India 25 Manufacture of the SUESSEN Technology Components 27 Produce More and Better High Grade Worsted Fashion Fabric – Danmao Spinning Mills, China 31 HP-GX 5010 – The Top Weighting Arm for Worsted Spinning 36 Wilhelm Stahlecker GmbH (WST) – Centre for Research and Development 40 SUESSEN Customer Survey 2007 44 News 46 Advertisement: – Graf, Switzerland 47 – SUESSEN Product Range 48 Impressum No. 24 – July 2008 Published by Reprint of articles with reference Price : € 5.– Spindelfabrik Suessen GmbH permitted – Voucher copies desired Publication : once per year Dammstrasse 1, D-73079 Süssen, All rights reserved Information & Advertising Contact: Germany Spindelfabrik Suessen GmbH SPINNOVATION, Germany Editor in Chief : Peter Stahlecker fax + 49 (0) 71 62 15-367 Title registered® at German Patent Front Cover : e-mail: [email protected] Office EliCoreTwist® – EliTwist®CompactSet internet: www.suessen.com Copyright © 2008 with COREflex ® 2 SPINNOVATION No. -

India's Textile and Apparel Industry

Staff Research Study 27 Office of Industries U.S. International Trade Commission India’s Textile and Apparel Industry: Growth Potential and Trade and Investment Opportunities March 2001 Publication 3401 The views expressed in this staff study are those of the Office of Industries, U.S. International Trade Commission. They are not necessarily the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission as a whole or any individual commissioner. U.S. International Trade Commission Vern Simpson Director, Office of Industries This report was principally prepared by Sundar A. Shetty Textiles and Apparel Branch Energy, Chemicals, and Textiles Division Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive Summary . v Chapter 1. Introduction . 1-1 Purpose of study . 1-1 Data and scope . 1-1 Organization of study . 1-2 Overview of India’s economy . 1-2 Chapter 2. Structure of the textile and apparel industry . 2-1 Fiber production . 2-1 Textile sector . 2-1 Yarn production . 2-4 Fabric production . 2-4 Dyeing and finishing . 2-5 Apparel sector . 2-5 Structural problems . 2-5 Textile machinery . 2-7 Chapter 3. Government trade and nontrade policies . 3-1 Trade policies . 3-1 Tariff barriers . 3-1 Nontariff barriers . 3-3 Import licensing . 3-3 Customs procedures . 3-5 Marking, labeling, and packaging requirements . 3-5 Export-Import policy . 3-5 Duty entitlement passbook scheme . 3-5 Export promotion capital goods scheme . 3-5 Pre- and post-shipment financing . 3-6 Export processing and special economic zones . 3-6 Nontrade policies . -

Notes from Judith Mackenzie's Class on Spinning Icelandic Fibers

Icelandic Sheep Breeders of North America Volume 5, Number 1 Winter 2001 Article #2 Editor, Kathy Hayes Notes from Judith Mackenzie’s Class on Spinning Icelandic Fibers Susan Mongold Weaving makes the lightest fabrics. Using a brush like a scrub brush on the woven fabric after it is woven (or knitted), will produce a long fur-type nap. The tog makes very attractive rug warp. Icelandic locks can actually be separated into up to 5 different lengths and diameters. Each layer gets progressively finer as the length gets shorter. The last or finest coat (thel) is like cashmere. The shortest undercoat, or bottom coat, the down, makes a perfect lace yarn. Lace is best made from a 2-ply yarn as the undulated surface of the 2-ply yarn helps to lock or hold the stich in place. A rounder, smoother 3-ply yarn has a smoother and more slippery surface and will not hold the pattern as well. In order to have the fibers slip easily in the spinning process, spin from the tip end of a lock, then ply from the butt end and knit from the tip end. This will give the easiest spinning experience as you are taking advantage of the lay of the scales on the wool fibers. The most important thing in a spinning fiber is the “hand.” hand is the soft silky feel of the fiber to your hand or how it feels when you handle it. It has little bearing on the fiber diameter. Even a very fine fiber can have a rough hand, while a coarse fiber can have a nice hand. -

The Textile Machinery Collection at the American Textile History Museum a Historic Mechanical Engineering Heritage Collection

THE TEXTILE MACHINERY COLLECTION AT THE AMERICAN TEXTILE HISTORY MUSEUM A HISTORIC MECHANICAL ENGINEERING HERITAGE COLLECTION Textiles are an important part of our everyday lives. They clothe and comfort us, protect our first-responders, Introduction filter the air in our automobiles, and form the core of the fuselage in our newest aircraft. We enjoy their bright colors, wrap up in their warmth, and seldom give a second thought to how they make bicycles stronger and lighter or how they might be used to repair our vital organs. As textiles have changed from the first simple twisted fibers to high-tech smart fabrics, the tools and machinery used to make them have evolved as well. Drop spindles and spinning wheels have given way to long lines of spinning frames. And looms now use puffs of air instead of the human hand to insert the weft thread in a growing length of fabric. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, textile manufacture was the catalyst for the Industrial Revolution in America. It was the leading edge in the transformation from an agricultural to a manufacturing economy and started the move of significant numbers of people from rural areas to urban centers. With industrialization came a change in the way people worked. No longer controlled by natural rhythms, the workday demanded a life governed by the factory bell. On the consumer side, industrialization transformed textiles from one of a person’s most valuable possessions to a product widely available at incredibly low prices. For more than a century, textile mills in Great Britain and the United States dominated textile production and led the industrial revolution in both Europe and North America. -

Premium Wool Zone Exhibitors in Hall 5.2 (Exhibitor List As of 24 Jan 2018, by Alphabetical Order)

Premium Wool Zone exhibitors in Hall 5.2 (Exhibitor list as of 24 Jan 2018, by alphabetical order) Exhibitor in English Country Product Description Website Abraham Moon & Sons United Woolen fabrics for tailoring, jackets www.moons.co.uk Ltd Kingdom and suits. Suitable for both men and women's wear. Aris Industrial S A Peru Wool Fabrics & blends with www.aris.com.pe alpaca, pima cotton & other natural fibers. Beijing Vitality Textiles China www.vitalitytex.com Co Ltd Dechamps United Kingdom Dino Filarte Italy Dormeuil France Since 1842, Dormeuil has been www.dormeuil.com supplying the world leading fashion houses with luxury fabrics produced from exclusive fibres (Pashmina, Cashmere, Vicuna, Guanaco, etc.) Dugdale Bros & Co Ltd United www.dugdalebros.com Kingdom Essence Trading China Woolen fabric for suits, jackets www.essence-of- (Shanghai) Co Ltd and overcoats/shirting fabric for fashion.com total look. Holland & Sherry United Luxary worsted wool suiting fabrics www.hollandandsherry.com Kingdom plus a selection of silks, cashmere and cottons. Huddersfield Fine United Wool based fabric for better men’s www.hfwltd.com Worsteds Kingdom MTM clothing business. 1 Premium Wool Zone exhibitors in Hall 5.2 (Exhibitor list as of 24 Jan 2018, by alphabetical order) Loa Hai Shing Co Ltd Hong Kong The most luxurious fabric in the www.lhshk.com.hk world from 100s-250s wool, cotton, linen, silk, mohair, cashmere, vicuna, gold, diamond. Merino Brothers Hong Kong Premier English wool suiting fabric. www.merinobrothers.com Company Limited Scabal NV/SA United Scabal offers more than 5000 www.scabal.com Kingdom fabrics, each available for next day delivery. -

Spinning Yarns, Telling Tales About Textiles

News for Schools from the Smithsonian Institution, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Washington, D.C. 20560 SEPTEMBER 1980 Spinning Yarns, Telling Tales about Textiles Textiles Tell Stories: The "Age of Homespun" and in regard to spinning, weaving, and other aspects of Other Tales textile making. This exchange of ideas led to a great Consider, for example, the piece of cloth shown in many improvements and innovations in all the various figure 1. This piece of hand-loomed, plaid linen is aspects of textile making over time. Some of the most from the Age of Homespun-a period of American important of these developments are explained in the history lasting from colonial times up until the Civil next section of this article. Bull mummy-wrapping (from Egypt) War. During the Age of Homespun many of the necessi ties of life-including textiles-were made in the Textiles From Scratch: Fiber to Cloth home. This was especially true in remote rural areas, Traditionally the making of a piece of cloth involved .7l",;;;,;i1_ where practically every farm had its own plot of flax first the selection of an appropriate natural fiber. (For i.liIi!i,~;':;\';_-- a discussion of natural fibers, see the article on page (as well as its own flock of sheep) and there was a m1i'<!Si~ 4.) The fiber was then harvested and made ready for 1\ wool wheel and a flax wheel in every kitchen. -iW:Mii\ii\_ spinning into thread or yarn. After spinning, the yarn en@! The making of cloth for clothing and bedding de manded an enormous amount of time and energy was usually either knitted or woven into cloth. -

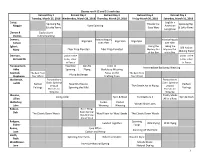

1 Classes Run 9-12 and 2-5 Each Day. Retreat Day 1 Tuesday, March 27

Classes run 9-12 and 2-5 each day. Retreat Day 1 Retreat Day 2 Retreat Day 3 Retreat Day 4 Retreat Day 5 Tuesday, March 27, 2018 Wednesday, March 28, 2018 Thursday, March 29, 2018 Friday March 30, 2018 Saturday, March 31, 2018 Casey, English v Spinning Big Boucle the Spinning Big Maggie Start Spinning American & Lofty Yarns Easy Way & Lofty Yarns Longdraw Clemes & Explorations Clemes in Drumcarding Demers, Knitting Happily Knitting Happily Ergo Spin Ergo Spin Ergo Spin Carson Ever After Ever After Egbert, Taking the Taking the Silk Fusion: Fiber Prep Elevated Fiber Prep Elevated Mystery Out Mystery Out Mary Making Paper of the Box of the Box Emerson, Locks in the Locks in the Bernadette Lens, Fiber Lens, Fiber in Focus in Focus Franquemont, Teaching Spindle Intro to Intermediate Backstrap Weaving Abby Spinning Plying Backstrap Weaving Gaustad, The Best from Focus on the The Best from Plying by Design Stephenie Your Wheel Drafting Zone Your Wheel Mackenzie, Extraordinary Extraordinary Judith Perfect Cloth: Spinning Bountiful Beasts: Cloth: Spinning Perfect Unusual The Gentle Art of Plying Unusual Pairings Spinning the Wild Pairings Threads for Threads for Weaving Weaving Moreno, Pretty Maids Living Color Spin & Nosh Yarnitecture 2 Spin & Nosh Jillian All in a Row Mullarkey, Pocket Pocket Woven Shoe Laces John Weaving Weaving Robson, Basic Things Every Spinner Deb The Classic Down Wools Wool Facts for Wool Geeks The Classic Down Wools Should Know About Wool Rodgers, Spinning Twisted Together Wild Plying Wild Plying Esther Loops Ruane, Love -

Class Descriptions for Web 2016 Ptx.Pptx

SMFAF 2016 Learn and Do Classes BEGINNING SPINNING Jennifer Bennett ON A WHEEL www.harmonywoolsalpacas.com Jenny Bennett is the owner of Date: Saturday, April 16, 2016 Harmony Wools, one of the Time: 9:30 AM-11:30 AM original founding alpaca farms Location: GSM Heritage Center, of the Southeast Alpaca Main Gallery Association and has always Cost: $45.00, includes Materials been focused on fiber. With Fee over 30 years of spinning, Maximum No. of Students: 6 processing, weaving, knitting, teaching and demonstrating, Jenny is a wealth of knowledge in the area of fiber and spinning. For anyone who wants to learn to spin yarn on a spinning wheel. This class will cover parts of the wheels, their maintenance and how to choose a fleece or roving to spin. High School or Adult newbie's or novice spinners are welcome. Students should bring their Spinning wheel and fiber if they have one. An assortment of fiber will be available at the class. With two weeks of advance notice, the instructor, can bring a couple of wheels as loaners. SMFAF 2016 Learn and Do Classes Intermediate Spinning Jennifer Bennett www.harmonywoolsalpacas.com Jenny Bennett is the owner of Harmony Wools, one of the Date: Saturday, April 16, 2016 original founding alpaca farms of Time: 12:00 PM-2:00 PM the Southeast Alpaca Location: GSM Heritage Center, Association and has always Main Gallery been focused on fiber. With over Cost: $45.00 30 years of spinning, Maximum No. of Students: 6 processing, weaving, knitting, teaching and demonstrating, Jenny is a wealth of knowledge in the area of fiber and spinning. -

Introduction to Spinning Wheels

presents An Introduction to Spinning Wheels: How to Use and How to Choose a Spinning Wheel elcome to the world of handspinning! So, you’ve decided to take the plunge and explore Wthe wonders of making your own yarn with a spinning wheel. Not only are you in for a treat, but you’ve also started at the right place. Learning how to spin your own yarn is pretty easy and straight forward, especially if you have access to great teachers. To make this free eBook, we pulled from some of our best content from the pages of Spin.Offmagazine. The oldest of Interweave’s publications, Spin.Off is a quarterly magazine that has been around since 1977 inspiring spinners new and old to make beautiful yarn and find enchanting ways to use it. We also host the spinning community, spinningdaily.com complete with blogs, forums, and free patterns, Spin.Off Autumn Retreat (SOAR)—an intense and inspirational week with like-minded spinners, and our series of workshop videos where the living treasures of the spinning world share their knowledge with you. We’re devoted to bringing you the best spinning teachers, the newest spinning ideas, and most inspirational creativity right to your mailbox, computer, and ultimately fingertips. We hope you enjoy your spinning journey—come tell us about it at spinningdaily.com. Happy spinning, Amy Clarke Moore [email protected] Indulge your passion for fiber with Spin.Off magazine Spin.Off brings you: • The best teachers teaching the best spinning tricks and techniques • The newest information: fibers, tools, books, events, people, and places • The warmest handspun projects that you can make • The coolest stories of spinning history and tradition Subscribe Now! Call (800) 767-9638 or go to spinoffmagazine.com Copyright Spin.Off® magazine, Interweave Press LLC. -

Master Spinner Handbook Content in This Document Is Current As of Time of Printing

Master Spinner Handbook Content in this document is current as of time of printing. Check the Master Spinner website for any recent changes Table of Contents Website:www.oldscollege.ca/programs/continuing-education/fibre-arts Administrative Information 1. Master Spinners Program Introduction and Policies ....................................................................... 1 2. Frequently Asked Questions .......................................................................................................... 6 3. APA Format (Formatting and Style Guide Summary) ................................................................. ..9 4. Level 6 In-Depth Study Policy ................................................................................................... .11 5. In-Depth Study Permission and License…………………………………………………………...16 6. In-Depth Study Proposal Submission Form ................................................................................ ..17 7. In-Depth Study Guidelines…………………………………………………………………….…...19 8. Levels 1-6 Competency Profiles .................................................................................................. 21 Technical Information 8. Twist Per Inch ............................................................................................................................ 29 9. Count ......................................................................................................................................... 33 10. Review of Spinning Techniques ................................................................................................