Globalization, Obsolescence, Migration and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

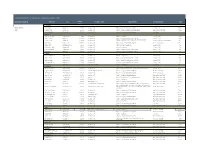

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

Conroe, Texas

Conroe, Texas Outlets at Conroe is undergoing a complete redevelopment amidst the enormous growth occurring in and around the City of Conroe. With the influx of corporate offices and master-planned communities, the North Houston area will become the workplace and home to tens of thousands of people in the next few years. The new Outlets at Conroe will be poised to deliver top outlet brands and a wide variety of dining options in a family-friendly environment for this growing constituency. Outlets at Conroe will ultimately be comprised of 340,000 square feet of retail and restaurants. The immediate area already boasts nearly 185,000 cars per day, and is just 30 minutes from George W. Bush International Airport and 50 miles from Houston. LOCATION SHOPPING CENTERS WITHIN 50 MILES OF Conroe, Texas OUTLETS AT CONROE I-45, at exit 90, approximately 50 miles north AERIAL DRIVING DISTANCE of downtown Houston. DISTANCE APPROX. DRIVE TIME A. Teas Crossing, Conroe .79 Mile 2 Miles MARKET JCPenney 2 Minutes Houston B. Conroe Marketplace, Conroe 1 Mile 2 Miles Kohl’s Ross Dress for Less 2 Minutes Shoe Carnival T.J. Maxx C. Market Street, The Woodlands 14 Miles 14 Miles Brooks Brothers The Cinemark at Market Street Theatre 18 Minutes J. Crew kate spade new york Tiffany & Co. Tommy Bahama D. The Woodlands Mall, The Woodlands 14 Miles 14 Miles Dillard’s JCPenney 18 Minutes Macy’s Nordstrom E. Deerbrook Mall, Humble 27 Miles 42 Miles Dillard’s JCPenney 48 Minutes Macy’s F. Willowbrook Mall, Houston 28 Miles 40 Miles Dillard’s JCPenney 48 Minutes Macy’s Nordstrom Rack G. -

Annual Report 2016 Is to Own and Operate

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 IS TO OWN AND OPERATE BEST-IN-CLASS RETAIL PROPERTIES THAT PROVIDE AN O U R OUTSTANDING ENVIRONMENT MISSION AND EXPERIENCE FOR OUR COMMUNITIES, RETAILERS, EMPLOYEES, CONSUMERS AND SHAREHOLDERS. 3 ALA MOANA CENTER Dear Shareholder, Our mission is to own and operate best-in-class retail properties that provide an outstanding environment and experience for our communities, retailers, employees, consumers and shareholders. Our core values are the DNA that make employees of GGP a family: Humility, Attitude, Do the Right Thing, Together and Own It. A winning culture creates a winning team. Retail real estate is ever evolving and so is GGP. Effective January 2017, we formally changed our name to GGP Inc. from General Growth Properties, Inc. The name change reinforces our mission and evolution to a pure-play owner of high quality retail properties in the U.S. Financial Results We believe GGP can generate long term average annual EBITDA growth of 4% to 5% from increases in contractual rent and occupancy, positive releasing spreads and income from redevelopment activities and acquisitions, taking into account nominal expense growth. 2016 was a year of achievements in the face of headwinds. Since 2014, more than 40 national retailers declared bankruptcy, representing 950 leases covering over three million square feet. On an annual basis, these leases represented nearly $180 million of rental revenue. We have more than overcome the rent and occupancy loss from these bankruptcies. Our 2016 results included same store NOI growth of 4.4% and EBITDA growth of 9.3%. We increased the dividend by nearly 13% and paid a special dividend resulting in a total common stock dividend of $1.06 per share. -

Program Guide

PROGRAM GUIDE 1900 Main • P.O.Box 61429 • Houston, TX 77208-1429 713-225-0119 • 713-652-8969 TDD • RideMETRO.org 1900 Main P.O.Box 61429 Houston, TX 77208-1429 713-225-0119 713-652-8969 TDD RideMETRO.org Dear METROLift Rider: Welcome to METROLift! The METROLift Program Guide will introduce you to METROLift transportation and provide the basic information you need to use the service. Upon request, this information is available in other formats. METROLift is a shared-ride public transit service. In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), travel times and the timeliness of service are comparable to METRO’s fixed- route bus service. Please read this policy brochure carefully to familiarize yourself with the type and level of service that METROLift provides. Remember that you have a responsibility to use accessible fixed-route METRO bus and rail service when possible. Our goal is to provide safe and reliable transportation. If, after reading this manual, you have questions regarding METROLift, please call the METROLift Customer Service and Eligibility Department at 713-225-0119. 1 CONTENTS Updated MAY 2021 METRO Bus and Rail Service ............................................................................... 4-5 METROLift Freedom Q® Card ..................................................................................6 What Is METROLift And How Does It Work? ....................................................... 6-7 METROLift is Public Transportation .........................................................................7 -

Freestanding Restaurant for Lease 6705 Fondren Rd, Houston, Texas, 77036 Property Information

FOR LEASE FREESTANDING RESTAURANT FOR LEASE 6705 FONDREN RD, HOUSTON, TEXAS, 77036 PROPERTY INFORMATION: • Freestanding building w/ Drive- thru • 2,550 SF former Whataburger on +/- 0.48 AC / 20,908 SF • Adjacent to PlazAmericas Mall (32 retail tenants) and nearby Walgreens, La Michoacana, Arena Theatre, Chick-fil-A, Whataburger, Wingstop, and Blaze Pizza • Ideal Uses: Freestanding restaurant, commissary kitchen, ghost kitchen, retail use • 1 Mile from Houston Baptist University Campus and 1.5 miles from Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital • Very dense residential area (269,905 population within 3 miles), neighbors Westchase and Galleria areas Contact: Campbell Anderson Greg Lee 915.433.4853 281.299.5764 [email protected] [email protected] The information contained herein was obtained through sources deemed reliable; however, Orr Realty Corporation makes no guarantees, warranties, or representa- Tel: 713.468.2600 | Fax: 713.468.7774 tions as to the completeness or accuracy thereof. The presentation of this property is submitted subject to errors, omissions, change in design, change of price prior 5400 Katy Freeway, Suite 100 to sale or lease, or withdrawal without notice. Houston, Texas 77007 FOR LEASE FREESTANDING RESTAURANT FOR LEASE 6705 FONDREN RD, HOUSTON, TEXAS, 77036 Demographics: 1 Mile Radius Population: 10,901 Households: 4,282 Total Daytime Pop: 20,073 Avg HH Income: $75,986 2 Mile Radius Population: 61,004 Households: 24,461 Total Daytime Pop: 83,636 Avg HH Income: $91,114 3 Mile Radius Population: 134,105 Households: 53,675 -

Securities and Exchange Commission Form 8-K Current Report Simon Property Group, Inc

QuickLinks -- Click here to rapidly navigate through this document SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): May 17, 2002 (May 8, 2002) SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-14469 046268599 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission (IRS Employer of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 115 WEST WASHINGTON STREET 46204 INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 317.636.1600 Not Applicable (Former name or former address, if changed since last report) Item 5. Other Events On May 8, 2002, the Registrant issued a press release containing information on earnings for the quarter ended March 31, 2002 and other matters. A copy of the press release is included as an exhibit to this filing. On May 9, 2002, the Registrant held a conference call to discuss earnings for the quarter ended March 31, 2002 and other matters. A transcript of this conference call is included as an exhibit to this filing. On May 17, 2002, the Registrant made available additional ownership and operation information concerning the Registrant, SPG Realty Consultants, Inc. (the Registrant's paired-share affiliate), Simon Property Group, L.P., and properties owned or managed as of March 31, 2002, in the form of a Supplemental Information package, a copy of which is included as an exhibit to this filing. The Supplemental Information package is available upon request as specified therein. -

Almeda Macy's Stays

4040 yearsyears ofof coveringcovering SSouthouth BBeltelt Voice of Community-Minded People since 1976 Thursday, January 12, 2017 Email: [email protected] www.southbeltleader.com Vol. 41, No. 49 Dobie parent meeting set Dobie High School will hold a parent night Thursday, Jan. 12, in the auditorium at 6:30 p.m. for incoming freshmen for the 2017-2018 Almeda Macy’s stays; Pasadena goes school year. School offi cials say they cannot ex- nate more than 10,000 jobs – 3,900 directly re- is pleased with the announcement. press enough the importance of this meeting, as By James Bolen tive or are no longer robust shopping destina- The Macy’s Almeda Mall location was spared tions due to changes in the local retail shopping lated to the closures and an additional 6,200 due “We are delighted the Macy’s list has been they will share important course registration in- to company restructuring. published, and as we expected, the Almeda formation with parents and students before they closure this past week when the retail giant an- landscape,” Macy’s CEO Terry Lundgren said in nounced the sites of 68 stores it plans to close a statement. Opened in 1962, the 209,000-squre-foot Pasa- Macy’s is not part of the nationwide store clos- register for classes for the upcoming school dena Town Square Macy’s will account for 78 ings,” Felton said. “Macy’s has always shown year. There will be an update on the new fresh- this year in an effort to cut costs amid lower The announcement came fresh on the heels sales. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey

American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey 2016 Code List 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ANCESTRY CODE LIST 3 FIELD OF DEGREE CODE LIST 25 GROUP QUARTERS CODE LIST 31 HISPANIC ORIGIN CODE LIST 32 INDUSTRY CODE LIST 35 LANGUAGE CODE LIST 44 OCCUPATION CODE LIST 80 PLACE OF BIRTH, MIGRATION, & PLACE OF WORK CODE LIST 95 RACE CODE LIST 105 2 Ancestry Code List ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) 001-099 . ALSATIAN 001 . ANDORRAN 002 . AUSTRIAN 003 . TIROL 004 . BASQUE 005 . FRENCH BASQUE 006 . SPANISH BASQUE 007 . BELGIAN 008 . FLEMISH 009 . WALLOON 010 . BRITISH 011 . BRITISH ISLES 012 . CHANNEL ISLANDER 013 . GIBRALTARIAN 014 . CORNISH 015 . CORSICAN 016 . CYPRIOT 017 . GREEK CYPRIOTE 018 . TURKISH CYPRIOTE 019 . DANISH 020 . DUTCH 021 . ENGLISH 022 . FAROE ISLANDER 023 . FINNISH 024 . KARELIAN 025 . FRENCH 026 . LORRAINIAN 027 . BRETON 028 . FRISIAN 029 . FRIULIAN 030 . LADIN 031 . GERMAN 032 . BAVARIAN 033 . BERLINER 034 3 ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) (continued) . HAMBURGER 035 . HANNOVER 036 . HESSIAN 037 . LUBECKER 038 . POMERANIAN 039 . PRUSSIAN 040 . SAXON 041 . SUDETENLANDER 042 . WESTPHALIAN 043 . EAST GERMAN 044 . WEST GERMAN 045 . GREEK 046 . CRETAN 047 . CYCLADIC ISLANDER 048 . ICELANDER 049 . IRISH 050 . ITALIAN 051 . TRIESTE 052 . ABRUZZI 053 . APULIAN 054 . BASILICATA 055 . CALABRIAN 056 . AMALFIAN 057 . EMILIA ROMAGNA 058 . ROMAN 059 . LIGURIAN 060 . LOMBARDIAN 061 . MARCHE 062 . MOLISE 063 . NEAPOLITAN 064 . PIEDMONTESE 065 . PUGLIA 066 . SARDINIAN 067 . SICILIAN 068 . TUSCAN 069 4 ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) (continued) . TRENTINO 070 . UMBRIAN 071 . VALLE DAOSTA 072 . VENETIAN 073 . SAN MARINO 074 . LAPP 075 . LIECHTENSTEINER 076 . LUXEMBURGER 077 . MALTESE 078 . MANX 079 . -

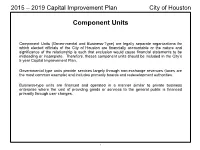

Component Units

2015 – 2019 Capital Improvement Plan City of Houston Component Units Component Units (Governmental and Business-Type) are legally separate organizations for which elected officials of the City of Houston are financially accountable or the nature and significance of the relationship is such that exclusion would cause financial statements to be misleading or incomplete. Therefore, theses component units should be included in the City’s 5 year Capital Improvement Plan. Governmental type units provide services largely through non-exchange revenues (taxes are the most common example) and includes primarily boards and redevelopment authorities. Business-type units are financed and operated in a manner similar to private business enterprise where the cost of providing goods or services to the general public is financed primarily through user charges. 1 2015 – 2019 Capital Improvement Plan City of Houston Table of Component Units Unit Has CIP? CIP as Of: Governmental Type City Park Redevelopment Authority N East Downtown Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Fifth Ward Redevelopment Authority N Fourth Ward Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Greater Greenspoint Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Greater Houston Convention and Visitors Bureau N Gulfgate Redevelopment Authority N Hardy Near Northside Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 HALAN – Houston Area Library Automated Network Board N Houston Arts Alliance N Houston Downtown Park Corporation N Houston Forensic Science LGC, Inc. N Houston Media Source N Houston Parks Board, Inc. Y FY15-19 Houston Parks Board LGC., Inc. N Houston Public Library Foundation N Houston Recovery Center LGC N Lamar Terrace Public Improvement District N Land Assemblage Redevelopment Authority N Leland Woods Redevelopment Authority N Leland Woods Redevelopment Authority II N Main Street Market Square Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Memorial City Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Memorial-Heights Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Midtown Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Miller Theatre Advisory Board, Inc. -

Building Technology Consultants, Inc

Law Firms . Porter & Hedges, LLP . Arnstein & Lehr, LLP . Reminger Co., LPA . Barnes & Thornburg, LLP . Roetzel & Andress . Blackburn Domene & Burchett PLLC . Segal McCambridge Singer & . Blitz, Bardgett & Deutsch, LC Mahoney . Bradley & Riley . SmithAmundson . Bryce Downey & Lenkov, LLC . Thompson, Coe, Cousins & Irons, L.L.P. Chiumento McNally, LLC . Waldeck and Patterson, P.A. Clingen Callow & McLean, LLC . Whyte Hirschboeck Dudek, SC . Conway & Mrowiec . Wilson Elser Moskowitz Edelman & . Donovan Hatem LLP Dicker, LLP . FeldmanWasser Commercial Property . Fisher Kanaris, P.C. Owners/Managers . Flaherty & Youngerman, PC . 900 North Michigan, Urban Retail . Franco Moroney Buenik LLC Properties, Co. Hall & Evans, LLC . Advanced Property Specialists . Holland & Knight, LLP . Aquascape, Inc. Hurtado Zimmerman, SC . AutoZone, Inc. K&L Gates . Belmont Village Senior Living . Kovitz, Shifrin, Nesbit . Bentall Kennedy, LP . LaBarge, Campbell & Lyon . Buca, Inc. Laurie & Brennan LLP . C.B. Richard Ellis . Lorance & Thompson, P.C. Citigroup Center . Litchfield Cavo, LLP . Colliers International . Macdonald Devin, PC . Development Management Associates . Maisel & Associates . Edgemark Asset Management, LLC . McNeal, Schick, Archibald & Biro, Co., L.P.A. Elevation Real Estate Partners . Merlin Law Group . Fashion Outlets of Chicago . Monteleone & McCrory, LLP . Federal Realty Investment Trust . Much Shelist, PC . Florida Capital Land Corporation . Niew Legal Partners, P.C. Foster Bank . Pachter, Gregory & Finocchiaro, PC . Galleria at Houston, Urban Retail Properties, Co. Peckar & Abramson, P.C . General Growth Properties . Penland & Hartwell, LLC . Hamilton Partners, Inc. Pietragallo Gordon Alfano Bosick & Raspanti, LLP . Harristown Development Corporation Building Technology Consultants, Inc. 1845 East Rand Road, Suite L-100 Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004 Main: (847) 454-8800 | www.btc.expert Page: 2 of 5 Commercial Property Community Associations Owners/Managers (Continued) . -

New Student Guide Fall 2018

NEW STUDENT GUIDE FALL 2018 Table of Contents 3 Welcome 38 Disability Services for Students (DSS) 4 Building by Floor Application Process 6 Directory Accommodations Possible 8 Locations of Interest 39 Financial Aid Office 10 Admissions – Cost of Attendance Application Information 12 Bookstore 41 Fitness Center 13 Bursar 42 Health Care for TWU – Houston 14 Bursar – Payment Highlights Immunizations 15 Bursar – Installment Payments 44 International Student Services 16 Bursar – Payment Options 45 Library Services 19 Campus Ministries Academic Resource Center (ARC) 20 Career Connections Center (CCC) 46 Library Research Services Resume Reviews and Mock Interviews ARC Collections and Resources Career Readiness Workshops ARC Use Guidelines and Seminars Assistance for Students Career Advising Appointments 47 Parking and Transportation Resource Library and Guides Garage Associated with TWU 23 CCC – Career Readiness Fannin South Park & Ride Lot Job Postings Public Parking at 1020 Holcombe TWU Connect TMC Contract Parking (POP) Job Search Web Sites Nursing Job Search Sites 48 Parking and Transportation Student Organization Presentations METRO Q Card for Full Time Students 24 Central Receiving/Copy Center 49 Pioneer Center for Student Excellence 26 Computer Lab & OoT Overview 50 Registrar’s Office 27 Computer Lab Use – Guidelines 52 Registration & Online Service – 28 Computer Information Pioneer Portal 29 Computer Info – Pioneer Portal, Blackboard & Canvas 53 Student Life Office 54 ID Badge Station 30 Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) 56