The Journals of Lieutenant John Pickell, 1836-1837

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Publication SJ92-SP16 LAKE JESSUP RESTORATION

Special Publication SJ92-SP16 LAKE JESSUP RESTORATION DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION HATER BUDGET AND NUTRIENT BUDGET Prepared for: ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT P.O. Box 1429 Palatka, Florida Prepared By: Douglas H. Keesecker HATER AND AIR RESEARCH, INC. Gainesville, Florida May 1992 File: 91-5057 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Page 1 of 2) Section Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i-1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 PURPOSE 1-1 1.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA 1-2 2.0 DATA COMPILATION 2-1 2.1 HISTORICAL DATA 2-1 2.1.1 Previous Studies 2-1 2.1.2 Climatoloqic Data 2-3 2.1.3 Hydrologic Data 2-4 2.1.4 Land Use and Cover Data 2-6 2.1.5 On-site Sewage Disposal System (OSDS) Data 2-8 2.1.6 Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP1 Data 2-9 2.1.7 Surface Water Quality Data . 2-10 3.0 WATER BUDGET 3-1 3.1 METHODOLOGY 3-1 3.1.1 Springflow and Upward Leakage 3-2 3.1.2 Direct Precipitation 3-4 3.1.3 Land Surface Runoff 3-4 3.1.4 Shallow Groundwater Inflow 3-6 3.1.5 Septic Tank (OSDS1 Inflows 3-7 3.1.6 Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent 3-8 3.1.7 Surface Evaporation 3-8 3.1.8 Surface Water Outflows 3-9 3.2 RESULTS - WATER BUDGET 3-10 3.3 DISCUSSION 3-16 3.4 ESTIMATE OF ERROR 3-18 3.4.1 Sprinoflow and Upward Leakage 3-18 3.4.2 Direct Precipitation 3-19 3.4.3 Land Surface Runoff 3-19 3.4.4 Shallow Groundwater Inflow 3-20 3.4.5 Septic Tank (OSDS1 Inflows 3-21 3.4.6 Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent 3-22 3.4.7 Surface Evaporation 3-22 3.4.8 Surface Water Outflows 3-22 LAKE JESSUP[WP]TOC 052192 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Page 2 of 2) Section Page 4.0 NUTRIENT BUDGETS 4-1 4.1 METHODOLOGY 4-1 4.1.1 Direct Precipitation Loading 4-2 4.1.2 Land Surface Runoff Loading 4-3 4.1.3 Shallow Groundwater Inflow Loading 4-3 4.1.4 Septic Tank Loading 4-4 4.1.5 Wastewater Treatment Plant Loading 4-4 4.1.6 St. -

Professional Paper SJ98-PP1

Professional Paper SJ98-PP1 5ohns * A Professional Paper SJ98-PP1 THE UPPER ST. JOHNS RIVER BASIN PROJECT THE ENVIRONMENTAL TRANSFORMATION OF A PUBLIC FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT by Maurice Sterling Charles A. Padera St. Johns J^iver Water Management District Palatka, Florida 1998 Northwest Florida Water Management District anagement Southwest Florida Water Management District St. Johns River Water Management District South Florida Water Management District The St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) was created by the Florida Legislature in 1972 to be one of five water management districts in Florida. It includes all or part of 19 counties in northeast Florida. The mission of SJRWMD is to manage water resources to ensure their continued availability while maximizing both environmental and economic benefits. It accomplishes its mission through regulation; applied research; assistance to federal, state, and local governments; operation and maintenance of water control works; and land acquisition and management. Professional Papers are published to disseminate information collected by SJRWMD in pursuit of its mission. Copies of this report can be obtained from: Library St. Johns River Water Management District P.O. Box 1429 Palatka, FL 32178-1429 Phone: (904) 329-4132 Professional Paper SJ98-PP1 The Upper St. Johns River Basin Project The Environmental Transformation of a Public Flood Control Project Maurice Sterling and Charles A. Padera St. Johns River Water Management District, Palatka, Florida ABSTRACT During the 1980s, the Upper St. Johns River Basin Project was transformed into a national model of modern floodplain management. The project is sponsored jointly by the St. Johns River Water Management District and the U.S. -

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13Th) Edition

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13th) Edition T OF EN CO M M T M R E A R P C E E D U N A I C T I E R D E S M T A ATES OF U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RDML Timothy Gallaudet., Ph.D., USN Ret., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere National Ocean Service Nicole R. LeBoeuf, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Ocean Services and Coastal Zone Management Cover image courtesy of Megan Greenaway—Great Salt Pond, Block Island, RI III Preface Distances Between United States Ports is published by the Office of Coast Survey, National Ocean Service (NOS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), pursuant to the Act of 6 August 1947 (33 U.S.C. 883a and b), and the Act of 22 October 1968 (44 U.S.C. 1310). Distances Between United States Ports contains distances from a port of the United States to other ports in the United States, and from a port in the Great Lakes in the United States to Canadian ports in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. Distances Between Ports, Publication 151, is published by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and distributed by NOS. NGA Pub. 151 is international in scope and lists distances from foreign port to foreign port and from foreign port to major U.S. ports. The two publications, Distances Between United States Ports and Distances Between Ports, complement each other. -

William Selby Harney: Indian Fighter by OLIVER GRISWOLD We Are Going to Travel-In Our Imaginations-A South Florida Route with a Vivid Personality

William Selby Harney: Indian Fighter By OLIVER GRISWOLD We are going to travel-in our imaginations-a South Florida route with a vivid personality. We are going back-in our imaginations-over a bloody trail. We are going on a dramatic military assignment. From Cape Florida on Key Biscayne, we start on the morning of De- cember 4, 1840. We cross the sparkling waters of Biscayne Bay to within a stone's throw of this McAllister Hotel where we are meeting. We are going up the Miami River in the days when there was no City of Miami. All our imaginations have to do is remove all the hotels from the north bank of the Miami River just above the Brickell Avenue bridge- then in the clearing rebuild a little military post that stood there more than a hundred years ago. At this tiny cluster of stone buildings called Ft. Dallas, our expedition pauses for farewells. We are going on up to the headwaters of the Miami River-and beyond-where no white man has ever been before. The first rays of the sun shed a ruddy light on a party of 90 picked U.S. soldiers. They are in long dugout canoes. The sunrise shines with particular emphasis on the fiery-red hair of a tall officer. It is as if the gleaming wand of destiny has reached down from the Florida skies this morning to put a special blessing on his perilous mission. He commands the flotilla to shove off. But before we join him on his quest for a certain villainous redskin, let us consider who this officer is. -

2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida: Sections 303(D), 305(B), and 314 Report and Listing Update

2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida: Sections 303(d), 305(b), and 314 Report and Listing Update Division of Environmental Assessment and Restoration Florida Department of Environmental Protection June 2020 2600 Blair Stone Rd. Tallahassee, FL 32399-2400 floridadep.gov 2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida, June 2020 This Page Intentionally Blank. Page 2 of 160 2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida, June 2020 Letter to Floridians Ron DeSantis FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF Governor Jeanette Nuñez Environmental Protection Lt. Governor Bob Martinez Center Noah Valenstein 2600 Blair Stone Road Secretary Tallahassee, FL 32399-2400 June 16, 2020 Dear Floridians: It is with great pleasure that we present to you the 2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida. This report meets the Federal Clean Water Act reporting requirements; more importantly, it presents a comprehensive analysis of the quality of our waters. This report would not be possible without the monitoring efforts of organizations throughout the state, including state and local governments, universities, and volunteer groups who agree that our waters are a central part of our state’s culture, heritage, and way of life. In Florida, monitoring efforts at all levels result in substantially more monitoring stations and water quality data than most other states in the nation. These water quality data are used annually for the assessment of waterbody health by means of a comprehensive approach. Hundreds of assessments of individual waterbodies are conducted each year. Additionally, as part of this report, a statewide water quality condition is presented using an unbiased random monitoring design. These efforts allow us to understand the state’s water conditions, make decisions that further enhance our waterways, and focus our efforts on addressing problems. -

The Breeding Range of the Black-Necked Stilt

248 The Wilson Bulletin-December, 1929 foot a constant reminder of the disagreeable experience. It is probable that hunger and the memory of source of sustenance are respectively stronger and more accurate in this muscular, bold creature than any recollection of pain or inconvenience which may have been caused at or near the source of food supply.- GEORGE MIKSCH SUTTON, Game Commission, Harrisburg, Pa. The Breeding Range of the Black-necked Stilt.-The breeding range of the Black-necked Stilt (Ilimantopus mexicanus) has been steadily increasing throughout different parts of southern and central Florida during the last few years. Where it was not found at all a few years ago it now breeds. In 1909 I found these birds nesting at Kissimmee and also at Lake Kissimmce on Rabbit Island. In 1915 they bred in numbers at Lake Harney, Seminole County. These places are still used as breeding places to the present date, May, 1929. They breed at Marco Island, some of the Keys. Puzzle Lake, Seminole County, Mer- ritts’ Island, along the St. Johns’ River between Sanford and Lake Harney, and at Geneva Ferry. The latest places discovered were at Turkey Hammock, Osceola County, which is where the Kissimee River begins at the south end of Lake Kissimee. About a dozen pairs were found evidently breeding, judging from their behavior, by Messrs. Arthur H. Howell and W. H. Ball, and me, on May 12, 1929. We also found four breeding pairs at Alligator RlufI, which is along the Kissimee River, on May 11, 7929. In March, 1908, March, 1910, and in 1912, I had covered this same territory and failed to see Rlack-necked Stilts in these two places. -

Your Guide to Eating Fish Caught in Florida

Fish Consumption Advisories are published periodically by the Your Guide State of Florida to alert consumers about the possibility of chemically contaminated fish in Florida waters. To Eating The advisories are meant to inform the public of potential health risks of specific fish species from specific Fish Caught water bodies. In Florida February 2019 Florida Department of Health Prepared in cooperation with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and Agriculture and Consumer Services, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 2019 Florida Fish Advisories • Table 1: Eating Guidelines for Fresh Water Fish from Florida Waters (based on mercury levels) page 1-50 • Table 2: Eating Guidelines for Marine and Estuarine Fish from Florida Waters (based on mercury levels) page 51-52 • Table 3: Eating Guidelines for species from Florida Waters with Heavy Metals (other than mercury), Dioxin, Pesticides, Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), or Saxitoxin Contamination page 53-54 Eating Fish is an important part of a healthy diet. Rich in vitamins and low in fat, fish contains protein we need for strong bodies. It is also an excellent source of nutrition for proper growth and development. In fact, the American Heart Association recommends that you eat two meals of fish or seafood every week. At the same time, most Florida seafood has low to medium levels of mercury. Depending on the age of the fish, the type of fish, and the condition of the water the fish lives in, the levels of mercury found in fish are different. While mercury in rivers, creeks, ponds, and lakes can build up in some fish to levels that can be harmful, most fish caught in Florida can be eaten without harm. -

U N S U U S E U R a C S

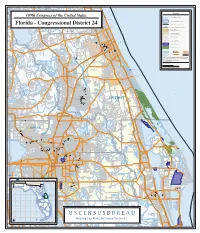

PUTNAM Legend (Ocean Shore Blvd) Halifax StHwy A1A 109th Congress of the United States River DISTRICT Lake Healy Cowpond Lake 24 Ormond-By-The-Sea Big Lake Louise DISTRICT 2 KANSAS OKLAHOMA Ormond ERIE 1 Beach Lake Disston Yonge St FLAGLER Turley C StHwy A1A (Atlantic Ave) e Holly n t e Hill r StHwy 11 40 ) S d y R t St H w d or StRd 19 Pierson (Dan F P o w Lake George e r L in Lake Shaw Lake e Pierson Justice Cain Lake S Tymber Creek Rd StHwy 430 (Mason Ave) Lpga Blvd Rd 40) Indigo Dr N (St Bill France Blvd Fort Belvoir 40 S Ridgewood Ave wy t StH H w y Ave B 5 95 A Midway Ave ( Payne Creek N Industrial Coral Sea Ave o Daytona Pkwy v Catalina Dr a Yosemite NP Lake Winona Terminal Dr R Beach d ) Midway Ave tHwy 40 Caraway Daytona Beach S Lake Williamson Blvd Shores Wildcat Lake Astor Big Tree Rd Interstate Hwy Other Major Road Lake Dias Slayton Ave Water Body 44 StHwy Lake Clifton 40 St Johns River Pine St South Other Road Schimmerhorne Lake StHwy 400 (Beville Rd) Daytona U.S. Hwy R Stream 56 Railroad i North Grasshopper Lake d g ) e e w v A o o South Grasshopper Lake n d o 92 t A 17 Rd Bay Clark w v Jolly Ford Rd la e un (D 1 Orange Rd 42 y De Leon Springs w H Chain O t 4 S Lake L i tt International Speedway Blvd Port Orange Lake Dexter le Farles Lake H T o a m Lake Daugharty w o C k r a Ponce F Lake Woodruff a r Buck Lake m Inlet s Stagger Mud Lake R d 0 2 4 6 Kilometers MARION Billies StHwy 421 (Taylor Rd) W Bay o o 0 2 4 6 Miles Tick Island d la Mud Lake nd A B l l ex v a d StHwy 19 nd e r Springs Coast Guard Station Cre Ponce de -

Floods in Florida Magnitude and Frequency

UNITED STATES EPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR- ., / GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLOODS IN FLORIDA MAGNITUDE AND FREQUENCY By R.W. Pride Prepared in cooperation with Florida State Road Department Open-file report 1958 MAR 2 CONTENTS Page Introduction. ........................................... 1 Acknowledgements ....................................... 1 Description of the area ..................................... 1 Topography ......................................... 2 Coastal Lowlands ..................................... 2 Central Highlands ..................................... 2 Tallahassee Hills ..................................... 2 Marianna Lowlands .................................... 2 Western Highlands. .................................... 3 Drainage basins ....................................... 3 St. Marys River. ......_.............................. 3 St. Johns River ...................................... 3 Lake Okeechobee and the everglades. ............................ 3 Peace River ....................................... 3 Withlacoochee River. ................................... 3 Suwannee River ...................................... 3 Ochlockonee River. .................................... 5 Apalachicola River .................................... 5 Choctawhatchee, Yellow, Blackwater, Escambia, and Perdido Rivers. ............. 5 Climate. .......................................... 5 Flood records ......................................... 6 Method of flood-frequency analysis ................................. 9 Flood frequency at a gaging -

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Statewide Alligator Harvest Data Summary

FWC Home : Wildlife & Habitats : Managed Species : Alligator Management Program FLORIDA FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION COMMISSION STATEWIDE ALLIGATOR HARVEST DATA SUMMARY YEAR AVERAGE LENGTH TOTAL HARVEST FEET INCHES 2000 8 8 2,552 2001 8 8.2 2,268 2002 8 3.7 2,164 2003 8 4.6 2,830 2004 8 5.8 3,237 2005 8 4.9 3,436 2006 8 4.8 6,430 2007 8 6.7 5,942 2008 8 5.1 6,204 2009 8 0 7,844 2010 7 10.9 7,654 2011 8 1.2 8,103 Provisional data 2000 STATEWIDE ALLIGATOR HARVEST DATA SUMMARY AVERAGE LENGTH TOTAL AREA NO AREA NAME FEET INCHES HARVEST 101 LAKE PIERCE 7 9.8 12 102 LAKE MARIAN 9 9.3 30 104 LAKE HATCHINEHA 8 7.9 36 105 KISSIMMEE RIVER (POOL A) 7 6.7 17 106 KISSIMMEE RIVER (POOL C) 8 8.3 17 109 LAKE ISTOKPOGA 8 0.5 116 110 LAKE KISSIMMEE 7 11.5 172 112 TENEROC FMA 8 6.0 1 402 EVERGLADES WMA (WCAs 2A & 2B) 8 8.2 12 404 EVERGLADES WMA (WCAs 3A & 3B) 8 10.4 63 405 HOLEY LAND WMA 9 11.0 2 500 BLUE CYPRESS LAKE 8 5.6 31 501 ST. JOHNS RIVER 1 8 2.2 69 502 ST. JOHNS RIVER 2 8 0.7 152 504 ST. JOHNS RIVER 4 8 3.6 83 505 LAKE HARNEY 7 8.7 65 506 ST. JOHNS RIVER 5 9 2.2 38 508 CRESCENT LAKE 8 9.9 23 510 LAKE JESUP 9 9.5 28 518 LAKE ROUSSEAU 7 9.3 32 520 LAKE TOHOPEKALIGA 9 7.1 47 547 GUANA RIVER WMA 9 4.6 5 548 OCALA WMA 9 8.7 4 549 THREE LAKES WMA 9 9.3 4 601 LAKE OKEECHOBEE (WEST) 8 11.7 448 602 LAKE OKEECHOBEE (NORTH) 9 1.8 163 603 LAKE OKEECHOBEE (EAST) 8 6.8 38 604 LAKE OKEECHOBEE (SOUTH) 8 5.2 323 711 LAKE HANCOCK 9 3.9 101 721 RODMAN RESERVOIR 8 7.0 118 722 ORANGE LAKE 8 9.3 125 723 LOCHLOOSA LAKE 9 3.4 56 734 LAKE SEMINOLE 9 1.5 16 741 LAKE TRAFFORD -

Middle St. Johns River Minimum Flows and Levels Hydrologic Methods Report

TECHNICAL PUBLICATION SJ2004-2 MIDDLE ST. JOHNS RIVER MINIMUM FLOWS AND LEVELS HYDROLOGIC METHODS REPORT Northwest Florida Water Management Suwannee District River Water Management District St. Johns River Water Management District Southwest Florida Water Management District South Florida Water Management District The St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) was created by the Florida Legislature in 1972 to be one of five water management districts in Florida. It includes all or part of 18 counties in northeast Florida. The mission of SJRWMD is to ensure the sustainable use and protection of water resources for the benefit of the people of the District and the state of Florida. SJRWMD accomplishes its mission through regulation; applied research; assistance to federal, state, and local governments; operation and maintenance of water control works; and land acquisition and management. This document is published to disseminate information collected by SJRWMD in pursuit of its mission. Copies of this document can be obtained from: Library St. Johns River Water Management District 4049 Reid Street • P.O. Box 1429 Palatka, FL 32178-1429 Phone: (386) 329-4132 Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The middle St. Johns River (MSJR) is being considered as a possible alternative water supply source to help meet the projected future increased demand for water in the St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) (Figure ES1). Although other factors may ultimately be more limiting, minimum flows and levels (MFLs) will provide the initial limits to surface water withdrawals from the MSJR. The basic task in analyzing changes to a hydrologic system is to quantify those changes and assess their acceptability. -

F L O R I D a Atlantic Ocean

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 4, Chapter 9 19 SEP 2021 81°30'W 81°W 11491 Jacksonville 11490 DOCTORS LAKE ATL ANTIC OCEAN 11492 30°N Green Cove Springs 11487 Palatka CRESCENT LAKE 29°30'N Welaka Crescent City 11495 LAKE GEORGE FLORIDA LAKE WOODRUFF 29°N LAKE MONROE 11498 Sanford LAKE HARNEY Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 4—Chapter 9 LAKE JESUP NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 4, Chapter 9 ¢ 301 St. Johns River (1) (8) ENCs - US5FL51M, US5FL57M, US5FL52M, US- Fish havens 5FL53M, US5FL84M, US5FL54M, US5FL56M (9) Numerous fish havens are eastward of the entrance to Charts - 11490, 11491, 11492, 11487, 11495, St. Johns River; the outermost is about 31 miles eastward 11498 of St. Johns Light. (10) (2) St. Johns River, the largest in eastern Florida, is Prominent features about 248 miles long and is an unusual major river in (11) St. Johns Light (30°23'10"N., 81°23'53"W.), 83 that it flows from south to north over most of its length. feet above the water, is shown from a white square tower It rises in the St. Johns Marshes near the Atlantic coast on the beach about 1 mile south of St. Johns River north below latitude 28°00'N., flows in a northerly direction jetty. A tower at Jacksonville Beach is prominent off and empties into the sea north of St. Johns River Light in the entrance, and water tanks are prominent along the latitude 30°24'N.