Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

Unit 2 Marcus Clarke : the Seizure of the Cyprus

UNIT 2 MARCUS CLARKE : THE SEIZURE OF THE CYPRUS Structure Objectives Introduction Marcus Clarke 2.2.1 From Foreign OfZce to Foreign Shore 2.2.2 Man of Many Talents His Natural Life Themes in Clarke " 2.4.1 Marcus Clarke in the 20&Century The Szimre of the Cyprus- Text 2.5.1 Analysing The Seizure of the Cyprus 2.5.2 Action in The Seizure of the Cyprus 2.5.3 Characterisation 2.5.4 Narrative Technique 2.5.5 Contextualising The Seizure of the Cyprus 2.5.6 Highlights Let us Sum up Questions Suggested Reading 2.0 OBJECTIVES The primary motive behind this unit is to provide you with some of the critical information surrounding the life and works of a great writer like Marcus Clarke. We shall, look into his biographical details, the circumstances related to the birth of his creativity, his position amongst the other short fiction writers of the age, and hs contribution to the development of Australian short fiction. 2.1 INTRODUCTION It is generally believed that the short story in Australia began with the writings of Henry Lawson. For most literary critics writing (of the short story 1 short fiction) before Lawson was not worth much critical attention. H M Green states in his introduction to the short story between 1850 to 1890 that, "the short stories of the period were many in number but poor in quality." He regards most of the short fiction before Lawson as mere 'sketches' in comparison with Lawson's stories. The short story as a genrc gained popularity chiefly on account of it being published regularly in the Sydney Bulletin of the 1890s. -

Marcus Clarke: Confronting Spectacle with Spectacle in for the Term of His Natural Life

Stephen F. Austin State University SFA ScholarWorks English 502: Research Methods English 12-9-2014 Marcus Clarke: Confronting Spectacle with Spectacle in For the Term of His Natural Life Mary E. Perkins Stephen F Austin State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/english_research_methods Part of the Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Perkins, Mary E., "Marcus Clarke: Confronting Spectacle with Spectacle in For the Term of His Natural Life" (2014). English 502: Research Methods. 8. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/english_research_methods/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in English 502: Research Methods by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Perkins ENG 502 Dr. Courtney Adams Wooten December 4, 2014 Marcus Clarke: Confronting Spectacle with Spectacle in For the Term of His Natural Life While Marcus Clarke’s For the Term of His Natural Life is unquestionably a classic text of the Australian literary canoni, oftentimes the importance of Clarke’s journalism as influential antecedents to his novel is underappreciated. In “Marcus Clarke: The Romance of Reality,” John Conley outlines how Clarke’s journalism career affected his literature, such as sensitivity to historical accuracy, a sense of audience and reader interest, and even funding for his research visit to the Tasmanian prisons. In addition to skills and access, Clarke’s journalism experience also put him in a unique position to observe nineteenth century Melbourne. -

George Gordon Mccrae - Poems

Classic Poetry Series George Gordon McCrae - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive George Gordon McCrae(9 May 1833 – 15 August 1927) George Gordon McCrae was an Australian poet. <b>Early life</b> McCrae was born in Leith, Scotland; his father was Andrew Murison McCrae, a writer; his mother was Georgiana McCrae, a painter. George attended a preparatory school in London, and later received lessons from his mother. Georgiana and her four sons emigrated to Melbourne in 1841 following her husband who emigrated in 1839. <b>Career</b> After a few years as a surveyor, McCrae joined the Victorian Government service, eventually becoming Deputy Registrar-General, and also a prominent figure in literary circles. Most of his leisure time was spent in writing. His first published work was Two Old Men's Tales of Love and War (London, 1865). His son <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/hugh-mccrae/">Hugh McCrae</a> also a poet, produced a volume of memoirs (My Father and My Father's Friends) about George and his association with such literary figures as <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/henry-kendall/">Henry Kendall</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/adam-lindsay-gordon/">Adam Lindsay Gordon</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/richard-henry- horne/">Richard Henry Horne</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/marcus-clarke/">Marcus Clarke</a>. George McCrae wrote novels, stories, poetry, and travel sketches, and illustrated books. After his retirement, unpublished manuscripts entitled 'Reminiscences—Experiences not Exploits' contain detailed descriptions of events from his youth and present a record of the early European part of Melbourne country-side. -

The Australian Imagination

Introduction to Australian Society: The Australian Imagination Class code SOC-UA 9TBA Instructor Dr Toby Martin Details [email protected] Consultation hours: Wednesdays 2:30pm-4:30pm Class Details Introduction to Australian Society: The Australian Imagination Wednesdays 9:30am Lecture Theatre Ground Floor 10:30-1:30 Tutorials 3rd Floor NYU Sydney Academic Centre Science House, 157 Gloucester St, The Rocks. Prerequisites None Class The Australian imagination is wondrous, vast, quirky and full of contradictions. Australians like to Description see their nation as, variously: the ‘lucky country’, yet with a debt to pay for the theft of Indigenous people’s land; the ‘land of the fair go’, which cruelly detains refugees; a place with a satirical sense of humour, coupled with a noticeably sentimental worldview; a multicultural nation with a history of a ‘white Australia policy’; a place proud of its traditions of egalitarianism and mateship, with rules about who is allowed in ‘the club’; a place with distinctive local traditions, which takes many of its cues from global culture; a place with a history of anti-British and anti-American sentiment that also has had strong political allegiances and military pacts with Britain and the USA; a place of a laid- back, easy going attitude with a large degree of Governmental control of individual liberties; a highly urbanised population that romances ‘the bush’ and ‘the outback’ as embodying ‘real’ Australia; and a place with a history of progressive social policy and a democratic tradition, which has never undergone a revolution. This course will provide ways of making sense of these contradictions. -

Vestures of the Past: the Other Historicisms of Victorian Aesthetics

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Vestures Of The Past: The Other Historicisms Of Victorian Aesthetics Timothy Chandler University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chandler, Timothy, "Vestures Of The Past: The Other Historicisms Of Victorian Aesthetics" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3434. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3434 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3434 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vestures Of The Past: The Other Historicisms Of Victorian Aesthetics Abstract The importance of history to Victorian culture, and to nineteenth-century Europe more generally, is readily apprehended not only from its historiography, but also from its philosophy, art, literature, science, politics, and public institutions. This dissertation argues that the discourse of aesthetics in Victorian Britain constitutes a major area of historical thinking that, in contrast to the scientific and philosophical historicisms that dominated nineteenth-century European intellectual culture, focuses on individual experience. Its starting point is Walter Pater’s claim that we are born “clothed in a vesture of the past”—that is, that our relation to ourselves is historical and that our relation to history is aesthetic. Through readings of aesthetic theory and art criticism, along with works of historiography, fiction, poetry, and visual art, this dissertation explores some of the ways in which Victorian aesthetics addresses the problem of the relationship between the sensuous representation and experience of the historical, on the one hand, and the subjects of such representation and experience, on the other. -

Online Walking with the Flâneur

online New Writing from In this Issue Western Australia Sherman Young Walking with Fiction Sunil Badami Poetry Nandi Chinna the Flâneur Essays Ross Gibson Reviews ‘The Swamp’ “…suburbs fall away and we forget Nandi Chinna our urgent imperatives; our feet sink into the lake’s edge giddy with the sky’s reflection” Westerly Online Special Issue 1, online ‘Walking with the Flâneur’, 2016 Notice of Intention Publisher Walking with Westerly has converted the full backfile of Westerly Centre, The University of Western Australia, Australia Westerly (1956–) to electronic text, available Editor the Flâneur to readers and researchers on the Westerly Catherine Noske website, www.westerlymag.com.au. This work has been supported by a grant from Editorial Advisors the Cultural Fund of the Copyright Agency Amanda Curtin (prose) Limited. Cassandra Atherton (poetry) All creative works, articles and reviews Editorial Consultants converted to electronic format will be correctly Barbara Bynder attributed and will appear as published. Delys Bird (The University of Western Australia) Copyright will remain with the authors, and the Tanya Dalziell (The University of Western Australia) material cannot be further republished without Paul Genoni (Curtin University) authorial permission. Westerly will honour any Dennis Haskell (The University of Western Australia) requests to withdraw material from electronic Douglas Kerr (University of Hong Kong) publication. If any author does not wish their John Kinsella (Curtin University) work to appear in this format, please -

New Zealand's Neglected Nineteenth Century Serial Novels

Submerged Below the Codex Line: New Zealand’s Neglected Nineteenth Century Serial Novels J.E. TRAUE The compilation of a checklist of nineteenth-century New Zealand novels and novellas published as serials and never issued as monographs, which provides the core evidence on which this paper is based, was inspired by Lydia Wevers’ article in Pacific Highways in 2013.1 She was questioning why New Zealand doesn’t measure up to Australia’s output of great nineteenth-century novels, and providing some very cogent answers based on the evidence currently available. However, I suspected, based on some research dating back to the 1980s and 1990s, that another possible reason might be that New Zealand literary historians had based their analysis on only the novels available in monographic form, and that there may be a goodly taniwha or two, even a great one, lurking elsewhere as serials in the deeper waters of the newspapers and periodicals. What I found down there in the newspapers was far more than I had expected. New Zealand literary historians have been clearly aware of, but not overly concerned about, the novels serialized in the newspapers. Dennis McEldowney, in the first edition of the Oxford History of New Zealand Literature, noted that local newspapers “had periods when they were hospitable to local writers. They have hardly been explored as yet. W. H. New suggests that here, in the sketches of local life rather than in the more formal fiction and poetry, is the reservoir from which later writing grew.”2 Lawrence Jones, writing on the pioneer -

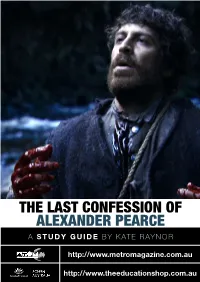

The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce a STUDY GUIDE by Kate Raynor

THE LAST CONFESSION OF ALEXANDER PEARCE A STUDY GUIDE BY KATE RAYNOR http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘It seems to me a full belly is prerequisite to all manner of good. Without that, no man will ever know what hunger can make you do.’ – Alexander Pearce Introduction the fledgling colony and a fellow Irish- important story, and would sit well man. At stake in their uneasy dialogue alongside The First Australians series n 1822, eight men escaped from the is nothing less than the soul of man. recently screened on SBS. most isolated and brutal prison on Utilizing the stunning and foreboding Iearth, Sarah Island in Van Diemen’s landscape of south-west Tasmania, The It could also work in the context of Land. Only one man survived and his Last Confession of Alexander Pearce Philosophy or Religious Studies, as it tale of betrayal, murder and cannibal- draws a visceral and compelling picture poses profound questions about the ism shocked the British establishment of the savagery and barbarism at the nature of good and evil, and redemp- to the core. The Last Confession of heart of the colony. It is an example of tion. It provides two intriguing character Alexander Pearce follows the final days Australian filmmaking at its very best. studies (Pearce and Conolly) and could of this man, Irish convict Alexander be used in English (film as text); and, Pearce, as he awaits execution. The Curriculum Links with the eloquence of its visual storytell- SCREEN EDUCATION year is 1824 and the British penal ing, it also has relevance to Film/Media colony of Van Diemen’s Land is little This film should be compulsory view- Studies. -

Editing a Manuscript Life of Marcus Clarke

Editing a Manuscript Life of Marcus Clarke CYRIL HOPKINS’S MARCUS arcus Clarke (1846-1881) is mainly Above: The wild known as the author of His Natural Western Victorian CLARKE, EDITED BY LAURIE Life (HNL), a novel that has remained scenery which inspired M Clarke’s famous HERGENHAN, KEN STEWART AND in print for 130 years since publication, as well as MICHAEL WILDING, PUBLISHED being adapted for stage and film. Mark Twain, for description of ‘the one, was impressed by a Sydney theatre produc- keynote of Australian BY AUSTRALIAN SCHOLARLY scenery’ as ‘weird tion on his visit to Australia, becoming an admirer melancholy’ PUBLISHING, MELBOURNE, WILL of Clarke’s work. BE LAUNCHED AT THE FRYER LIBRARY ON 21 JULY 2009. HERE, But Michael Wilding has established that Clarke LAURIE HERGENHAN SHARES THE was much more than a one-book author. He TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF wrote numerous short stories: of up-country life, EDITING A MANUSCRIPT WRITTEN Gothic romance and mystery, and also tales of early Australian history. He was a man of the A CENTURY AGO ABOUT ONE OF Melbourne theatre, as author and critic; and he AUSTRALIA’S MOST RENOWNED produced a steady stream of scintillating journal- WRITERS. ism about his adopted city: its doctors, lawyers, the post-gold-rush nouveaux riches, Bohemians, Unless otherwise stated, the photographs in this magazine are taken by the Fryer Library Editors Dr Chris Tiffin, Ros Follett, Laurie McNeice, Reproduction Service. The views expressed in Fryer Folios are those of the individual Cathy Leutenegger, Suzanne Parker and down-and-outs, looking beneath what he contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors or publisher. -

For the Term of His Natural Life

For the Term of His Natural Life Marcus Clarke This eBook was designed and published by Planet PDF. For more free eBooks visit our Web site at http://www.planetpdf.com/. To hear about our latest releases subscribe to the Planet PDF Newsletter. For the Term of His Natural Life DEDICATION TO SIR CHARLES GAVAN DUFFY My Dear Sir Charles, I take leave to dedicate this work to you, not merely because your nineteen years of political and literary life in Australia render it very fitting that any work written by a resident in the colonies, and having to do with the history of past colonial days, should bear your name upon its dedicatory page; but because the publication of my book is due to your advice and encouragement. The convict of fiction has been hitherto shown only at the beginning or at the end of his career. Either his exile has been the mysterious end to his misdeeds, or he has appeared upon the scene to claim interest by reason of an equally unintelligible love of crime acquired during his experience in a penal settlement. Charles Reade has drawn the interior of a house of correction in England, and Victor Hugo has shown how a French convict fares after the fulfilment of his sentence. But no writer—so far as I 2 of 898 For the Term of His Natural Life am aware—has attempted to depict the dismal condition of a felon during his term of transportation. I have endeavoured in ‘His Natural Life’ to set forth the working and the results of an English system of transportation carefully considered and carried out under official supervision; and to illustrate in the manner best calculated, as I think, to attract general attention, the inexpediency of again allowing offenders against the law to be herded together in places remote from the wholesome influence of public opinion, and to be submitted to a discipline which must necessarily depend for its just administration upon the personal character and temper of their gaolers. -

Richard Henry Horne (Richard Hengist Horne)

RICHARD HENRY HORNE (RICHARD HENGIST HORNE) RICHARD HENRY HORNE RICHARD HENGIST HORNE “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY HDT WHAT? INDEX RICHARD HENGIST HORNE RICHARD HENRY HORNE 1802 December 31, Friday: Richard Henry Horne was born in Edmonton, a northern suburb of London, as the eldest son of James Horne, a quartermaster in the 61st Regiment of Foot (South Gloucestershire). Intended for a military career like that of his father, he would be educated at a school in Edmonton, but then in a student rebellion at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich would be found to have, sin of sins, caricatured the headmaster. He was asked to leave, and entered the Sandhurst military college but would receive no commission. Upon graduation he would fail to obtain a position with the East India Company. By the Treaty of Bassein, the Peshwa of Poona ceded his independence and that of the Maratha Confederacy to the British East India Company. NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Richard Hengist Horne HDT WHAT? INDEX RICHARD HENRY HORNE RICHARD HENGIST HORNE 1823 Reading QUEEN MAB; A PHILOSOPHICAL POEM: WITH NOTES. BY PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY, a celebration of the merits of republicanism, atheism, vegetarianism, and free love, Richard Henry Horne determined that he also was going to make of himself a poet. LIFE IS LIVED FORWARD BUT UNDERSTOOD BACKWARD? — NO, THAT’S GIVING TOO MUCH TO THE HISTORIAN’S STORIES. LIFE ISN’T TO BE UNDERSTOOD EITHER FORWARD OR BACKWARD. “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Richard Hengist Horne HDT WHAT? INDEX RICHARD HENGIST HORNE RICHARD HENRY HORNE 1825 Mexico, while still subject to Spain in 1821, had granted land within the Mexican state of Texas to Moses Austin.