Evolution, Revolution, and Reform in Vienna: Franz Unger's Ideas On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eduard Fenzls Anteil

MARIA PETZ-GRABENBAUER ZUM LEBENSWERK VON EDUARD FENZL. DER BOTANISCHE GARTEN DER UNIVERSITÄT WIEN UND FENZLS BEITRAG AN DEN „GENERA PLANTARUM SECUNDUM ORDINES NATURALES DISPOSITA“ Ein gemeinsamer Weg „Vor allem muss man den Scharfsinn bewundern, mit dem es Fenzl gelingt, grössere Gruppen natürlich zu umgrenzen oder für zweifelhafte Gattungen den geeignetsten Platz im Systeme zu ermitteln. In dieser Beziehung sind die in Endlicher’s Generibus plantarum und in Ledebour’s Flora rossica bearbeiteten Familien als wahre Muster anzusehen. Hierin ist Fenzl mit Endlicher auf das Innigste verwandt; in der Beschrei- bung der einzelnen Arten übertrifft er ihn weit. Denn in dieser Richtung gebührt Fenzl das große Verdienst, dass er vorzüglich die organografisch und biologisch wichtigen Momente berücksichtigte und sich nicht bloß wie seine Vorgänger mit der Angabe der relativen Verhältnisse der einzelnen Theile begnügte, sondern sehr genaue absolute Messungen gebrauchte. So gelingt es ihm, einerseits seinen Beschreibungen eine große Genauigkeit zu verleihen, andererseits die von ihm aufgestellten Arten glücklich und natürlich zu begrenzen, so dass er stets die richtige Mitte zwischen zu großer Zer- splitterung in viele Arten, und den Vereinen von zu heterogenen Formen hält“.1 Mehr als 150 Jahre weitgehend unbeachtet blieben diese Ausführungen des Bota- nikers Heinrich Wilhelm Reichardt über den Anteil Eduard Fenzls an den „Genera plantarum secundum ordines naturales disposita“, die zwischen 1836 und 1840 von Stephan Ladislaus Endlicher veröffentlicht wurde. Mit diesem Werk gelang es Endli- cher neun Jahre vor seinem Tod, eine Übersicht des Pflanzenreiches herauszugeben, wie es seit den Arbeiten der Familie Jussieu Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts nicht wieder versucht worden war. -

Reconstructing the Fragmented Library of Mondsee Abbey

Reconstructing the Fragmented Library of Mondsee Abbey IVANA DOBCHEVA and VERONIKA WÖBER, Austrian National Library, Austria The Benedictine monastery of Mondsee was an important local centre for book production in Upper Austria already shortly after its foundation in 748. A central factor for the growth of the library were the monastic reform movements, which prompted the production of new liturgical books and consequently the discarding of older ones. When a bookbinding workshop was installed in the 15th century many of these manuscripts, regarded as useless, were cut up and re-used in bindings for new manuscripts, incunabula or archival materials. The aim of our two-year project funded by the Austrian Academy of Science (Go Digital 2.0) is to bring these historical objects in one virtual collection, where their digital facsimile and scholarly descriptions will be freely accessible online to a wide group of scholars from the fields of philology, codicology, history of the book and bookbinding. After a short glance at the history of Mondsee and the fate of the fragments in particular, this article gives an overview of the different procedures established in the project for the detecting and processing of the detached and in-situ fragments. Particular focus lays on the technical challenges encountered by the digitalisation, such as the work with small in-situ fragments partially hidden within the bookbinding. Discussed are also ways to address some disadvantages of digital facsimiles, namely the loss of information about the materiality of physical objects. Key words: Fragments, Manuscripts, Mondsee, Digitisation, Medieval library. CHNT Reference: Ivana Dobcheva and Veronika Wöber. -

BR0083 000 A.Pdf

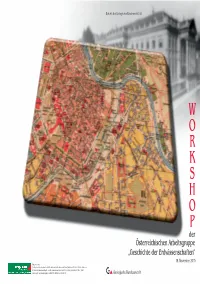

Umschlag 83-2010 Workshop.ps D:\ACINOM\Publikationen\Berichte der GBA\83-2010 Workshop GeschErdw\Umschlag 83-2010.cdr Donnerstag, 11. November 2010 15:31:54 Farbprofil: Deaktiviert Composite Standardbildschirm 100 100 Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 83 95 95 75 75 25 25 5 5 0 0 100 100 95 95 75 75 19. November 2010 Ausschnitt aus: 25 „G. Freytag's Verkehrsplan der k. k. Reichshaupt- & Residenzstadt Wien, Maßstab 1:15.000 – Mit vollständigem 25 Straßenverzeichnis und Angabe der Häusernummern, Druck und Verlag G. Freytag & Berndt, Wien, 1902“ 5 mit freundlicher Genehmigung von FREYTAG-BERNDT u. ARTARIA KG. Geologische Bundesanstalt 5 0 0 Workshop der Österreichischen Arbeitsgruppe „Geschichte der Erdwissenschaften“ 19. November 2010 Geologische Bundesanstalt Beiträge zum Workshop Redaktion: Bernhard Hubmann & Johannes Seidl Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 83 Wien, im November 2010 Impressum Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 83 ISSN 1017-8880 Wien, im November 2010 Workshop der Österreichischen Arbeitsgruppe „Geschichte der Erdwissenschaften“ 19. November 2010 Geologische Bundesanstalt Beiträge zum Workshop Vordere Umschlagseite: Ausschnitt aus: „G. Freytag’s Verkehrsplan der k. k. Reichshaupt- & Residenzstadt Wien, Maßstab 1:15.000 – Mit vollständigem Straßenverzeichnis und Angabe der Häusernummern, Druck und Verlag G. Freytag & Berndt, Wien, 1902“ mit freundlicher Genehmigung von FREYTAG-BERNDT u. ARTARIA KG (Kartographisches Institut und Verlag). Siehe dazu Beitrag von SUTTNER, HÖFLER & HOFMANN, S. 41 ff. Alle Rechte für das In- und Ausland vorbehalten © Geologische Bundesanstalt Medieninhaber, Herausgeber und Verleger: Geologische Bundesanstalt, A-1030 Wien, Neulinggasse 38, Österreich Die Autorinnen und Autoren sind für den Inhalt ihrer Arbeiten verantwortlich und sind mit der digitalen Verbreitung Ihrer Arbeiten im Internet einverstanden. -

Fremontia Journal of the California Native Plant Society

$10.00 (Free to Members) VOL. 40, NO. 1 AND VOL. 40, NO. 2 • JANUARY 2012 AND MAY 2012 FREMONTIA JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY THE NEW JEPSONJEPSON MANUALMANUAL THE FIRST FLORA OF CALIFORNIA NAMING OF THE GENUS SEQUOIA FENS:FENS: AA REMARKABLEREMARKABLE HABITATHABITAT AND OTHER ARTICLES VOL. 40, NO. 1 AND VOL. 40, NO. 2, JANUARY 2012 AND MAY 2012 FREMONTIA CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY CNPS, 2707 K Street, Suite 1; Sacramento, CA 95816-5130 FREMONTIA Phone: (916) 447-CNPS (2677) Fax: (916) 447-2727 Web site: www.cnps.org Email: [email protected] VOL. 40, NO. 1, JANUARY 2012 AND VOL. 40, NO. 2, MAY 2012 MEMBERSHIP Membership form located on inside back cover; Copyright © 2012 dues include subscriptions to Fremontia and the CNPS Bulletin California Native Plant Society Mariposa Lily . $1,500 Family or Group . $75 Bob Hass, Editor Benefactor . $600 International or Library . $75 Patron . $300 Individual . $45 Beth Hansen-Winter, Designer Plant Lover . $100 Student/Retired/Limited Income . $25 Brad Jenkins, Cynthia Powell, CORPORATE/ORGANIZATIONAL and Cynthia Roye, Proofreaders 10+ Employees . $2,500 4-6 Employees . $500 7-10 Employees . $1,000 1-3 Employees . $150 CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY STAFF – SACRAMENTO CHAPTER COUNCIL Executive Director: Dan Glusenkamp David Magney (Chair); Larry Levine Dedicated to the Preservation of Finance and Administration (Vice Chair); Marty Foltyn (Secretary) Manager: Cari Porter Alta Peak (Tulare): Joan Stewart the California Native Flora Membership and Development Bristlecone (Inyo-Mono): -

Jahresbericht 2019 Neue Folge 49 – Graz 2020 Jahresbericht 2019 Neue Folge 49 – Graz 2020

Jahresbericht 2019 Neue Folge 49 – Graz 2020 Jahresbericht 2019 Neue Folge 49 – Graz 2020 Herausgeber Universalmuseum Joanneum GmbH Mariahilferstraße 2–4 A-8020 Graz Geschäftsführung Kaufmännische Geschäftsführerin Alexia Getzinger Wissenschaftlicher Geschäftsführer Wolfgang Muchitsch Redaktion Karl Peitler Grafische Konzeption Lichtwitz – Büro für visuelle Kommunikation Satz Beatrix Schliber-Knechtl Umschlaggestaltung Leo Kreisel-Strauß und Karin Buol-Wischenau Abbildungen Umschlag Sujets CoSA – Center of Science Activities Illustrationen: Harald Niessner Druck Medienfabrik Graz ISBN 978-3-903179-26-4 Graz 2020 4 Vorwort Inhalt 6 Kuratorium 8 Generalversammlung & Aufsichtsrat 10 Wissenschaftliche & Kaufmännische Geschäftsführung Museumsabteilungen 14 Naturkunde 58 Archäologie & Münzkabinett 84 Schloss Eggenberg & Alte Galerie 118 Neue Galerie Graz 144 Kunsthaus Graz 164 Kunst im Außenraum 184 Kulturgeschichte 216 Volkskunde 254 Schloss Stainz 268 Schloss Trautenfels Serviceabteilungen 290 Interne Dienste 296 Außenbeziehungen 300 Abteilung für Besucher/innen 324 Museumsservice 338 Besuchsstatistik Vorwort 4 Das Jahr 2019, das letzte Jahr, bevor COVID-19 den gewohnten, geregelten Lauf der Welt durcheinanderwirbelte, war neben einem wieder sehr inten- siven Ausstellungsgeschehen in allen Häusern sowie einer regen Samm- lungstätigkeit gekennzeichnet von einer Erweiterung unserer Museen. Mit 1. Jänner 2019 wurde das Österreichische Freilichtmuseum Stübing nach monatelanger Vorbereitung in das Universalmuseum Joanneum eingeglie- dert und im Oktober 2019 das CoSA – Center of Science Activities im Joanneumsviertel nach mehrjähriger Planung in Kooperation mit dem Grazer Kindermuseum FRida & freD eröffnet. Diese Erweiterungen waren ausschlaggebend dafür, dass die Erfolgsent- wicklung der letzten Jahre 2019 erneut zu einem Rekordergebnis geführt hat. Mit 700.168 Besuchen konnte das beste Resultat in der 208-jährigen Geschichte des Joanneums verzeichnet werden, die Einnahmenerlöse sind demgemäß in den letzten 10 Jahren um 149 % gestiegen. -

Martius and Flora Brasiliensis, Names Not to Be Forgotten ♣

ACTA SCIENTIFIC AGRICULTURE (ISSN: 2581-365X) Volume 3 Issue 12 December 2019 Research Article Martius and Flora Brasiliensis, Names Not to be Forgotten ♣ João Vicente Ganzarolli de Oliveira* Senior Professor and Researcher of the Tércio Pacitti Institute of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil *Corresponding Author: João Vicente Ganzarolli de Oliveira, Senior Professor and Researcher of the Tércio Pacitti Institute of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Received: November 4, 2019; Published: November 29, 2019 DOI: 10.31080/ASAG.2019.03.0735 There are three stages of scientific discovery: first people deny it is true; then they deny it is important; finally they credit the wrong person. (…) How a person masters his fate is more important than what his fate is. Alexander von Humboldt Abstract This article focuses the life and work of the German botanist and explorer Karl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794-1868), notably his Flora Brasiliensis. Martius’ most important work is an unrivalled (and well succeeded) attempt to classify the plants (mostly angiosperms) of Brazil, a country of continental dimensions that encompasses one third of South America; in spite of the fact that the Flora Brasiliensis became a standard reference for the identification of Brazilian and South American vegetation in general, in Brazil, MartiusKeywords: and Martius; his magnificent Flora Braziliensis; work have Brazil;been systematically Plants; Nature relegated to oblivion. Introduction: without plants… that the Flora Brasiliensis became a standard reference for the iden- 2. The following lines concern the life and work of the German natu- One should bear in mind that, “In the face of the enormous amount ralist Karl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794-1868), notably his tification of Brazilian and South American vegetation in general Flora Brasiliensis. -

Lehre Und Lehrbücher Der Naturgeschichte an Der Universität Wien Von 1749 Bis 1849

©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, ISSN 1017-8880, Band 83, Wien 2010 BEITRÄGE Lehre und Lehrbücher der Naturgeschichte an der Universität Wien von 1749 bis 1849 Matthias Svojtka Anton Baumgartnerstr. 44/A4/092, A-1230 Wien; e-mail: [email protected] Blüht denn noch keine Stapelie?1 „Es werden also die Dinge, die um uns sind, nach jener Ordnung betrachtet, wie die Natur auf den Stufen der Organisatzion [sic!] vom Staube der Erde bis zum edlen Metalle, vom Metalle zur Pflanze, zum Thiere und Menschen hinaufsteigt. Dieses leistet die Naturgeschichte, welche eine sehr nützliche Anwendung noch dadurch erhält, wenn auch die Vertheilung der Produkten [sic!] auf unserm Erdball gezeiget wird“2. Die Naturgeschichte ist zunächst und vor allem eine beschreibende und – seit Carl von Linné (1707-1787) – systematisierende Wissenschaft. Beschrieben werden Naturkörper aus den „drei Reichen“ Mineralogie, Botanik und Zoologie, vornehmlich nach ihren äußeren Kennzeichen3. Dabei ist primär kein Gedanke an eine „Geschichte der Natur“, also eine Genese der Naturkörper im Laufe der Erdgeschichte, enthalten – Naturgeschichte darf hier noch mit Naturerzählung gleichgesetzt werden (EGGLMAIER 1988: VIII). Erst mit der zunehmenden „Verzeitlichung“ in den Naturwissenschaften in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts und dem Aufkommen des Begriffes „Biologie“ (nach unserem heutigen Verständnis) 4 im Jahr 1802 entwickelte sich die Naturgeschichte mehr und mehr von einer Beschreibung der Lebewesen zu einer Wissenschaft vom Leben (LEPENIES 1976)5. Der naturgeschichtliche Unterricht umfasste in Summe immer Inhalte aus den drei Reichen – Mineralogie, Botanik und Zoologie; in Wien kam es bereits 1749 an der Medizinischen Fakultät zur Einrichtung einer Lehrkanzel für Botanik (und Chemie). -

The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860

The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860 Conception – Implementation – Aftermath Edited by Christof Aichner and Brigitte Mazohl VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN DER KOMMISSION FÜR NEUERE GESCHICHTE ÖSTERREICHS Band 115 Kommission für Neuere Geschichte Österreichs Vorsitzende: em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Brigitte Mazohl Stellvertretender Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Reinhard Stauber Mitglieder: Dr. Franz Adlgasser Univ.-Prof. Dr. Peter Becker Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Ernst Bruckmüller Univ.-Prof. Dr. Laurence Cole Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margret Friedrich Univ.-Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Garms-Cornides Univ.-Prof. Dr. Michael Gehler Univ.-Doz. Mag. Dr. Andreas Gottsmann Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margarete Grandner em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Hanns Haas Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Wolfgang Häusler Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Ernst Hanisch Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gabriele Haug-Moritz Dr. Michael Hochedlinger Univ.-Prof. Dr. Lothar Höbelt Mag. Thomas Just Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Grete Klingenstein em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Alfred Kohler Univ.-Prof. Dr. Christopher Laferl Gen. Dir. Univ.-Doz. Dr. Wolfgang Maderthaner Dr. Stefan Malfèr Gen. Dir. i. R. H.-Prof. Dr. Lorenz Mikoletzky Dr. Gernot Obersteiner Dr. Hans Petschar em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Helmut Rumpler Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Martin Scheutz em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gerald Stourzh Univ.-Prof. Dr. Arno Strohmeyer Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Arnold Suppan Univ.-Doz. Dr. Werner Telesko Univ.-Prof. Dr. Thomas Winkelbauer Sekretär: Dr. Christof Aichner The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860 Conception – Implementation – Aftermath Edited by Christof Aichner and Brigitte Mazohl Published with the support from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 397-G28 Open access: Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License. -

Abhandlungen 2013 BAND 66 Igraphic T Ra St Rian T Us a He T S of T

T HAR C ABHANDLUNGEN 2013 BAND 66 IGRAPHIC T RA ST RIAN T US A HE T S OF T Vol. I THE PALEOZOIC ERA(THEM) Authors: Bernhard Hubmann [Coordinator] (Graz), Fritz Ebner (Leoben), Annalisa Ferretti (Modena), Kathleen Histon (Modena), Erika Kido (Graz), ARY SUCCESSIONS) IGRAPHIC UNI Karl Krainer (Innsbruck), Franz Neubauer (Salzburg), T Hans Peter Schönlaub (Kötschach-Mauthen) T & Thomas J. Suttner (Graz). RA T HOS T 2004 (SEDIMEN THE LI WERNER E. PILLER [Ed.] Geologische Bundesanstalt Address of editor: Werner E. Piller University of Graz Institute for Earth Sciences Heinrichstraße 26, A-8010 Graz, Austria [email protected] Addresses of authors: Bernhard Hubmann Franz Neubauer University of Graz University of Salzburg Institute for Earth Sciences Department of Geography and Geology Heinrichstraße 26, A-8010 Graz, Austria Hellbrunnerstraße 34, A-5020 Salzburg, Austria [email protected] [email protected] Fritz Ebner Hans Peter Schönlaub University of Leoben Past Director, Geological Survey of Austria Department of Geosciences/Geology and Economic Geology Kötschach 350, A-9640 Kötschach-Mauthen, Austria; Peter-Tunner-Straße 5, A-8700 Leoben, Austria [email protected] [email protected] Erika Kido, Thomas J. Suttner Annalisa Ferretti, Kathleen Histon University of Graz Università degli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia Institute for Earth Sciences Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra Heinrichstraße 26, A-8010 Graz, Austria Largo S. Eufemia 19, I-41121 Modena, Italy [email protected]; [email protected] [email protected]; [email protected], [email protected] Karl Krainer University of Innsbruck Institute of Geology and Paleontology Innrain 52, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria [email protected] Recommended citation / Zitiervorschlag PILLER, W.E. -

Cedroxylon Lesbium (Unger) Kraus from the Petrified Forest of Lesbos, Lower Miocene of Greece and Its Possible Relationship to Cedrus

N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh. 284/1 (2017), 75–87 Article E Stuttgart, April 2017 Cedroxylon lesbium (UNGER) KRAUS from the Petrified Forest of Lesbos, lower Miocene of Greece and its possible relationship to Cedrus Dimitra Mantzouka, Vasileios Karakitsios, and Jakub Sakala With 6 figures Abstract: The Petrified Forest of Lesbos has been the subject of the palaeobotanical research since the 19th century, but a number of inconsistencies still remain. One of them concerns the fossils described over 100 years ago that are characterized by lack of the accompanied illustrations, missing or even lost type material, rather general and uninformative descriptions and finally weak evidence about stratigra- phy and exact location of fossiliferous sites. We present here an accurate interpretation of Cedroxylon lesbium (UNGER) KRAUS from Sigri (Petrified Forest area, western peninsula of Lesbos Island), which is hosted at the collections of the Natural History Museum of Vienna, Austria. The specimen, which is designated here as a lectotype, is compared with living Cedrus wood, its attribution to Cedroxylon is discussed and finally, a new combination for its denomination is proposed: Taxodioxylon lesbium (UNGER) MANTZOukA & SAKALA, comb. nov. Key words: fossil conifer wood, modern wood of Cedrus, Petrified Forest of Lesbos, early Miocene, Mediterranean, Greece. 1. Introduction presents those in the annual fossils’ exhibition at the Landesmuseum Joanneum (Graz, Austria) in 1842 Lesbos Island is highly appreciated by the scientific (GROSS 1999). The Austrian Professor of Botany and community because of the occurrence of the famous Director of this museum’s Botanical garden FRANZ Miocene Petrified Forest at the western peninsula UNGER described this material (UNGER 1844, 1845, 1847, of the Island (Fig. -

International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences

International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences INHIGEO ANNUAL RECORD No. 50 Covering Activities generally in 2017 Issued in 2018 INHIGEO is A Commission of the International Union of Geological Sciences & An affiliate of the International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology Compiled and Edited by William R. Brice INHIGEO Editor Printed in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, USA, on request Available at www.inhigeo.com ISSN 1028-1533 1 2 CONTENTS INHIGEO Annual Record No. 50 (Published in August 2018 and covering events generally in 2017) INHIGEO BOARD………………………………………………………………………..…………..…..6 MESSAGES TO MEMBERS President’s Message: Barry Cooper..……………………………………………………….…….7 Secretary-General’s Report: Marianne Klemun...……………………………………………......8 Editor’s Message: William R. Brice…………………………………………………………….10 INHIGEO CONFERENCE REPORT INHIGEO Conference, Yerevan, Armenia 12 to 18 September 2017……………………………………………….…………….….12 "Personalities of the INHIGEO: From Madrid (2010) To Cape Town (2016)" By L. Kolbantsey and Z. Bessudnova…………………………………...……………....29 INHIGEO CONFERENCES 43rd Symposium – Mexico City, 12-21 November 2018………………………………………...35 Future Scheduled conferences………….…………………………………..……………………36 44th INHIGEO Symposium, Varese and Como (Italy), 2-12 September 2019………….36 45th INHIGEO Symposium – New Delhi, India, 2020……………...…………………..37 46th INHIGEO Symposium – Poland, 2021……………………………………………..37 OTHER CONFERENCES Symposium on the Birth of Geology in Argentinean Universities………...………………….…37 Austrian Working Group -

Shrubland Ecosystem Genetics and Biodiversity: Proceedings; 2000 June 13–15; Provo, UT

United States Department of Agriculture Shrubland Ecosystem Forest Service Genetics and Biodiversity: Rocky Mountain Research Station Proceedings Proceedings RMRS-P-21 September 2001 Abstract McArthur, E. Durant; Fairbanks, Daniel J., comps. 2001. Shrubland ecosystem genetics and biodiversity: proceedings; 2000 June 13–15; Provo, UT. Proc. RMRS-P-21. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 365 p. The 53 papers in this proceedings include a section celebrating the 25-year anniversary of the Shrub Sciences Laboratory (4 papers), three sections devoted to themes, genetics, and biodiversity (12 papers), disturbance ecology and biodiversity (14 papers), ecophysiology (13 papers), community ecology (9 papers), and field trip section (1 paper). The anniversary session papers emphasized the productivity and history of the Shrub Sciences Laboratory, 100 years of genetics, plant materials development for wildland shrub ecosystems, and current challenges in management and research in wildland shrub ecosystems. The papers in each of the thematic science sessions were centered on wildland shrub ecosystems. The field trip featured the genetics and ecology of chenopod shrublands of east-central Utah. The papers were presented at the 11th Wildland Shrub Symposium: Shrubland Ecosystem Genetics and Biodiversity held at the Brigham Young University Conference Center, Provo, UT, June 13–15, 2000. Keywords: wildland shrubs, genetics, biodiversity, disturbance, ecophysiology, community ecology Acknowledgments We thank the many people and organizations that assisted in the advance preparation and conduct of the symposium, anniversary celebration, and field trip. Brigham Young University President Merrill J. Bateman, Rocky Mountain Research Station Director Denver P. Burns, and Forest Service Vegetation Management and Protection Washington Office Director William T.