Great Achievements David B. Steinman by Weingardt.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It's the Way to Go at the Peace Bridge

The coupon is not an invoice. If you Step 3 Read the customer guide New Jersey Highway Authority Garden State Parkway are a credit card customer, you don’t carefully. It explains how to use E-ZPass have to worry about an interruption and everything else that you should know New Jersey Turnpike Authority New Jersey Turnpike in your E-ZPass service because we about your account. Mount your tag and New York State Bridge Authority make it easy for you by automatically you’re on your way! Rip Van Winkle Bridge replenishing your account when it hits Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge a low threshold level. Mid-Hudson Bridge Newburgh-Beacon Bridge For current E-ZPass customers: Where it is available. Bear Mountain Bridge If you already have an E-ZPass tag from E-ZPass is accepted anywhere there is an E-ZPass logo. New York State Thruway Authority It’s the Way another toll agency such as the NYS This network of roads aids in making it a truly Entire New York State Thruway including: seamless, regional transportation solution. With one New Rochelle Barrier Thruway, you may use your tag at the account, E-ZPass customers may use all toll facilities Yonkers Barrier Peace Bridge in an E-ZPass lane. Any where E-ZPass is accepted. Tappan Zee Bridge to Go at the NYS Thruway questions regarding use of Note: Motorists with existing E-ZPass accounts do not Spring Valley (commercial vehicle only) have to open a new or separate account for use in Harriman Barrier your tag must be directed to the NYS different states. -

Harlem River Waterfront

Amtrak and Henry Hudson Bridges over the Harlem River, Spuyten Duvyil HARLEM BRONX RIVER WATERFRONT MANHATTAN Linking a River’s Renaissance to its Upland Neighborhoods Brownfied Opportunity Area Pre-Nomination Study prepared for the Bronx Council for Environmental Quality, the New York State Department of State and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation with state funds provided through the Brownfield Opportunity Areas Program. February 2007 Acknowledgements Steering Committee Dart Westphal, Bronx Council for Environmental Quality – Project Chair Colleen Alderson, NYC Department of Parks and Recreation Karen Argenti, Bronx Council for Environmental Quality Justin Bloom, Esq., Brownfield Attorney Paula Luria Caplan, Office of the Bronx Borough President Maria Luisa Cipriano, Partnership for Parks (Bronx) Curtis Cravens, NYS Department of State Jane Jackson, New York Restoration Project Rita Kessler, Bronx Community Board 7 Paul S. Mankiewicz, PhD, New York City Soil & Water Conservation District Walter Matystik, M.E.,J.D., Manhattan College Matt Mason, NYC Department of City Planning David Mojica, Bronx Community Board 4 Xavier Rodriguez, Bronx Community Board 5 Brian Sahd, New York Restoration Project Joseph Sanchez, Partnership for Parks James Sciales, Empire State Rowing Association Basil B. Seggos, Riverkeeper Michael Seliger, PhD, Bronx Community College Jane Sokolow LMNOP, Metro Forest Council Shino Tanikawa, New York City Soil and Water Conservation District Brad Trebach, Bronx Community Board 8 Daniel Walsh, NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Project Sponsor Bronx Council for Environmental Quality Municipal Partner Office of Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrión, Jr. Fiscal Administrator Manhattan College Consultants Hilary Hinds Kitasei, Project Manager Karen Argenti, Community Participation Specialist Justin Bloom, Esq., Brownfield Attorney Paul S. -

Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Hourly Traffic on Bridges and Tunnels Dataset Overview

Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Hourly Traffic on Bridges and Tunnels Dataset Overview General Description MTA Bridges and Tunnels Created in 1933 by Robert Moses, MTA Bridges and Tunnels serves more than 800,000 vehicles each weekday — nearly 290 million vehicles each year — and carries more traffic than any other bridge and tunnel authority in the nation. All are within New York City, and all accept payment by E-ZPass, an electronic toll collection system that is moving traffic through MTA Bridges and Tunnels toll plazas faster and more efficiently. MTA Bridges and Tunnels is a cofounder of the E-ZPass Interagency Group, which has implemented seamless toll collection in 14 states, including New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia; tolls are charged electronically to a single E-ZPass account. See also: http://web.mta.info/mta/network.htm This dataset provides data showing the number of vehicles (including cars, buses, trucks and motorcycles) that pass through each of the nine bridges and tunnels operated by the MTA each hour. The dataset includes Plaza ID, Date, Hour, Direction, # Vehicles using EZ Pass, and # Vehicles using cash. Data Collection Methodology This data is collected on a weekly basis. The data is extracted directly from the EZ-Pass system database. Statistical and Analytic Issues Only in-bound (Staten Island-bound) traffic over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge is collected. The column labeled ETC refers to electronic toll collection. This is the number of vehicles that pass through each bridge or tunnel's toll plaza using E-ZPass. -

Commercial User Guide Page 1 FINAL 1.12

E-ZPass Account User Guide Welcome to the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission’s E-ZPass Commercial Account program. With E-ZPass, you will be able to pass through a toll facility without exchanging cash or tickets. It helps ease congestion at busy Pennsylvania Turnpike interchanges and works outside of Pennsylvania for seamless travel to many surrounding states; anywhere you see the purple E-ZPass sign (see attached detailed listing). The speed limit through E-ZPass lanes is 5-miles per hour unless otherwise posted. The 5-mile per hour limit is for the safety of all E-ZPass customers and Pennsylvania Turnpike employees. If you have any questions about your E-ZPass account, please contact your company representative or call the PTC E-ZPass Customer Service Center at 1.877.PENNPASS (1.877.736.6727) and ask for a Commercial E-ZPass Customer Service Representative. Information is also available on the web at www.paturnpike.com . How do I install my E-ZPass? Your E-ZPass transponder must be properly mounted following the instructions below to ensure it is properly read. Otherwise, you may be treated as a violator and charged a higher fare. Interior Transponder CLEAN and DRY the mounting surface using alcohol (Isopropyl) and a clean, dry cloth. REMOVE the clear plastic strips from the back of the mounting strips on the transponder to expose the adhesive surface. POSITION the transponder behind the rearview mirror on the inside of your windshield, at least one inch from the top. PLACE the transponder on the windshield with the E-ZPass logo upright, facing you, and press firmly. -

New York City Truck Route

Staten Island Additional Truck and Commercial Legal Routes for 53 Foot Trailers in New York City Special Midtown Manhattan Rules Cross Over Mirrors Requirement Legal Routes for 53 Foot Trailers 10 11 12 13 14 15 Vehicle Resources The New York City interstate routes approved for 53 foot trailers are: The two rules below apply in Manhattan Due to the height of large trucks, it can North d Terrace ● I-95 between the Bronx-Westchester county line and I-295 on New York City m be difficult for truck drivers to see what is h Throgs from 14 to 60 Streets, and from 1 to 8 ic R ● I-295 which connects I-95 with I-495 Rich mo Avenues, inclusive. They are in effect happening directly in front of their vehicles. 95 n Thompskinville d L L NYCDOT Truck and Commercial Vehicle 311 ● I-695 between I-95 and I-295 Te Neck r Broadway Cross Over Mirrors, installed on front of the cab race Information Cross between the hours of 7 AM and 7 PM daily, ● I-495 between I-295 and the Nassau-Queens county line Bronx 95 www.nyc.gov/trucks 95 Expwy except Sundays. There may be different of a truck, are a simple way of eliminating a ZIP Code Index Expwy Av ● I-678 between I-95 and the John F. Kennedy International Airport To New Jersey h Turnpike ut 695 restrictions on particular blocks. Check truck driver’s front “blind spots” and allows the 10301 Staten Island L-14 o ● I-95 between I-695 and the New Jersey state line on the upper level of the S NYCDOT Truck Permit Unit 212-839-6341 carefully. -

2016 New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes

2016 New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes TM NEW YORK CITY Bill de Blasio Polly Trottenberg Mayor Commissioner A member of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council 2016 New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes Contract C033467 2014-2015: PTDT14D00.E01 2015-2016: PTDT15D00.E01 2016-2017: PTDT16D00.E02 2017-2018: PTDT17D00.E02 The preparation of this report has been financed through the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Transit Administration and Federal Highway Administration. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Transit Administration, Federal Highway Administration or the State of New York. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. NYCDOT is grateful to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority Bridges and Tunnels (MTABT), the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ), and the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council (NYMTC) for providing data used to develop this report. This 2016 New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes Report was funded through the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council SFY 2017 Unified Planning Work Program project, Data Management PTDT17D00.E02, which was funded through matching grants from the Federal Transit Administration and from the Federal Highway Administration. Title VI Statement The New York Metropolitan Transportation Council is committed to compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, and all related rules and statutes. -

Nation's Largest Bridge and Tunnel Toll Authority Creates Advanced

Making New York City’s Roads Safer With GIS Nation’s Largest Bridge and Tunnel Toll Authority Creates Advanced Solution for Reducing Accidents In terms of traffic volume, the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Bridges and Tunnels (B&T) organization is the largest among the nation’s bridge and tunnel toll authorities. Also known as the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA), it serves more than one million people daily in the New York metropolitan area. As a constituent agency of the MTA, its dual role is to operate seven bridges and two tunnels as well as to provide surplus toll revenues to help support public transit. Its facilities include the Triborough Bridge, Throgs Neck Bridge, Verrazano Narrows Bridge, Bronx–Whitestone Bridge, Henry Hudson Bridge, Marine Parkway, Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge, Cross Bay Veterans Memorial Bridge, Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, and Queens Midtown Tunnel. More than 750,000 vehicles use these facilities each day. Ensuring optimized traffic flow is a mandate MTA B&T works at continuously, both in terms of day-to-day infrastructure maintenance and support and long-term planning and proactive problem solving. And one of the most advanced tools MTA B&T uses is GIS. The organization recently developed an advanced solution for analyzing traffic collision data and a host of other data sets to find new solutions to avoid potential traffic hazards. Developed by MTA B&T using ESRI’s ArcIMS and ArcView 8 software, the Collision Analysis Reporting System (CARS) is the flagship GIS application developed by MTA B&T. Donald Raimondi, budget and research analyst, MTA B&T, and manager of the project, and Greg Kurilla, GIS specialist at MTA B&T, developed CARS to provide managers with the tools to detect significant histories quickly and accurately and learn from them to make safer roadways. -

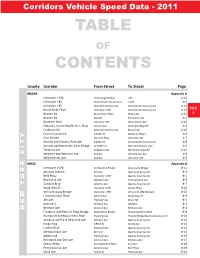

Table of Contents

Corridors Vehicle Speed Data - 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS County Corridor From Street To Street Page BRONX Appendix A Inerstate I‐278 Triborough Bridge I‐95 A‐15 Inerstate I‐87 Westchester County Line I‐278 A‐2 Inerstate I‐95 New York County Line Westchester County Line A‐14 Bronx River Pkwy Inerstate I‐278 Westchester County Line A‐13 TOC Boston Rd Bronx River Pkwy Ropes Ave A‐12 1 Boston Rd 3rd Ave E Tremont Ave A‐1 Bruckner Blvd Inerstate I‐87 Westchester Ave A‐16 Edward L Grant Hwy/Dr M. L. King Jerome Ave W Kingsbridge Rd A‐4 Fordham Rd New York County Line Boston Rd A‐10 Grand Concours e E 138th St Mosholu Pkwy S A‐6 Gun Hill Rd Gun Hill Pkwy Inerstate I‐95 A‐7 Jerome Ave/Central Park Ave E 204th St Westchester County Line A‐8 Jerome Ave/Macombs Dam Bridge W 169th St New York County Line A‐5 Tremont Ave Sedgwick Ave Williamsbridge Rd A‐11 Webster Ave/Melrose Ave 3rd Ave Westchester Ave A‐9 Westchester Ave 3rd Ave Inerstate I‐95 A‐3 KINGS Appendix B Inerstate I‐278 Verrazanno Bridge Kosciuszko Bridge B‐11 Atlantic Avenue 6th Ave Queens County Line B‐2 Belt Pkwy Inerstate I‐278 Queens County Line B‐5 Bushwick Ave Maspeth Ave Pennsylvania Ave B‐6 Conduit Blvd Atlantic Ave Queens County Line B‐7 State Hwy 27 Inerstate I‐278 Ocean Pkwy B‐20 Williamsburg Bridge Inerstate I‐278 Clinton St (Manhattan) B‐22 Fort Hamilton Pkwy Marine Ave State Hwy 27 B‐9 4th Ave Flatbush Ave Shore Rd B‐1 Avenue U Stillwell Ave Mill Ave B‐3 Bedford Ave Division Ave Emmons Ave B‐4 N E W Y O R K C I T Flatbush Ave/Marine Pkwy Bridge Manhattan Bridge Rockaway Point -

A Value-Pricing Toll Plan for the MTA Saving Drivers Time While Generating Revenue

A Value-Pricing Toll Plan for the MTA Saving Drivers Time While Generating Revenue By Charles Komanoff Komanoff Energy Associates for the Tri-State Transportation Campaign February 2003 TRI-STATE TRANSPORTATION CAMPAIGN: A VALUE-PRICING TOLL PLAN FOR THE M.T.A. 1 Executive Summary Key Finding A “value-pricing” toll plan for the MTA bridges and tunnels that raises peak-period one- way tolls to $5.00 while maintaining the current $3.50 toll for all other trips would generate increased revenues roughly equal to those expected from the MTA’s current flat-rate plan to raise all tolls to $4.00. The revenue increase would be approximately $100 million a year in either case. However, the value-pricing toll plan would also shave 1-2 minutes from the typical peak-period round-trip, a time saving worth as much as $36 million annually when aggregated over the millions of such trips made each year by commuters, truckers and other drivers. In contrast, the MTA toll plan would cut at most a quarter-minute from the average peak round-trip, and the associated time savings are likely to sum to no more than $7 million annually. Report Summary This report considers ways to modify the tolls charged on the MTA bridges and tunnels to increase revenue generation and ease chronic travel delays due to traffic congestion on or near the MTA crossings. It was commissioned by the Tri-State Transportation Campaign (TSTC), a non-profit advocacy group based in New York City promoting local and regional transportation policies that enhance community, mobility and sustainability. -

History and Projection of Traffic, Toll Revenues and Expenses

Attachment 6 HISTORY AND PROJECTION OF TRAFFIC, TOLL REVENUES AND EXPENSES AND REVIEW OF PHYSICAL CONDITIONS OF THE FACILITIES OF TRIBOROUGH BRIDGE AND TUNNEL AUTHORITY September 4, 2002 Prepared for the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority By 6-i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE 1 Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA) 1 Metropolitan Area Arterial Network 3 Other Regional Toll Facilities 4 Regional Public Transportation 5 TOLL COLLECTION ON THE TBTA FACILITIES 5 Current Toll Structure and Operation 5 E-ZPass Electronic Toll Collection System 8 Passenger Car Toll Rate Trends and Inflation 9 HISTORICAL TRAFFIC, REVENUES AND EXPENSES AND ESTIMATED/FORECAST NUMBERS FOR 2002 12 Traffic and Toll Revenue, 1991 - 2001 12 Traffic by Facility and Vehicle Class, 2001 14 Monthly Traffic, 2001 15 Impact of September 11 Terrorist Attack 16 Estimated Traffic and Toll Revenue, 2002 20 Operating Expenses 1991 – 2001 21 Forecast of Expenses, 2002 23 FACTORS AFFECTING TRAFFIC GROWTH 23 Employment, Population and Motor Vehicle Registrations 24 Fuel Conditions 28 Toll Impacts and Elasticity 30 Bridge and Tunnel Capacities 32 TBTA and Regional Operational and Construction Impacts 33 Other Considerations 40 Summary of Assumptions and Conditions 41 PROJECTED TRAFFIC, REVENUES AND EXPENSES 43 Traffic and Toll Revenue at Current Tolls 43 Traffic and Toll Revenue with Periodic Toll Increases 45 Operating Expenses 48 Net Revenues from Toll Operations 49 REVIEW OF PHYSICAL CONDITION 50 Review of Inspection Reports 51 Long-Term Outlook -

MTA Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment 2015-2034

MTA Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment 2015-2034 October 2013 Capital Needs Assessment 2015-2034 New York City Transit Long Island Rail Road Metro-North Railroad Bridges and Tunnels Capital Construction Bus Company October 2013 On the cover: An F train approaches New York City Transit’s Smith-9th Sts. station in Brooklyn. These R-160 cars were part of an order for over 1,600 cars that was completed in 2010. Located on the Culver Line Viaduct, the station is the highest elevated station in NYCT’s system. Originally opened in 1933, the station and viaduct have recently undergone a comprehensive rehabilitation to make structural repairs and modernize signals and other critical systems. Capital Needs Assessment 2015-2034 (This page is left intentionally blank) Capital Needs Assessment 2015-2034 Table of Contents Glossary ..................................................................................................................... 1 Prologue ................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 11 Preserving the Transit System’s Rich Heritage .............................................. 12 Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment .......................................................... 14 Rebuilding the System Expanding the System Rebuilding the System ................................................................................ 17 2015-2034 Continuing -

Henry Hudson Bridge Upper and Lower Level Roadway Rehabilitation

October 17, 2017 For Release IMMEDIATE Contact: MTA Press Office (212) 878-7440 Henry Hudson Bridge Upper and Lower Level Roadway Rehabilitation Starting October 20th, MTA Bridges and Tunnels will commence work to rehabilitate the upper and lower level roadways of the Henry Hudson Bridge. A signature part of this project will be the removal of columns and toll islands from the old toll plaza on the lower level roadway, which will improve traffic flow and allow for a smoother ride across the bridge. This work will initially close one lane on the northbound Henry Hudson Parkway from the Dyckman Street entrance up till the area of the former toll plaza leading to the bridge starting October 20th, followed by a traffic pattern shift on the southbound lower level in November. Work will then proceed concurrently on both levels in January 2018, requiring the closure of one lane in each direction, with two lanes always remaining open in both directions. The lower level pedestrian walkway will also be closed at this time and a free shuttle service will be provided from March to December to carry pedestrians and cyclists. The $86 million project will replace the last remaining sections of the 1930s era roadway decks and supporting structures. It is anticipated that this work will impact the traffic pattern for 19 months. The Henry Hudson Bridge opened in 1936 and it connects northern Manhattan to the Bronx. When it opened, it was the longest plate girder arch and fixed arch bridge in the world. Originally built with only one level, the bridge's design allowed for the construction of a second level if traffic demands increased.