Commemorating Those Who Lie in Sea Graves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Francisco Reef Divers June 2017 Volume XLV No. 6 1 SUP DIVING

San Francisco Reef Divers June 2017 Volume XLV No. 6 SUP DIVING VS. KAYAK By Mike Staninec urchins and kept looking into cracks and holes for On Saturday, May 20th, some of the dwindling fish, without much luck. After an hour or so Gene and aging freedive contingent of the San Francisco showed up and told me he had been diving in the Reef Divers assembled in Sausalito, eh, that would same cove, just a bit closer to shore. He had his limit be two of us, Gene Kramer and myself. The forecast of abs as well and had not seen any fish. I pointed for Mendocino coast was quite bit rougher than for out a spot where I had seen some small blues earlier Sonoma that day, so we had decided to stay and he said he'd check it out, and jumped back in. I south. We drove up to the coast through Bodega worked the bottom some more, and was very happy Bay, trying to scout to find a medium size China rockfish in a crack, out the conditions which I invited home along the coast, for dinner with my 38 starting at Salmon Special. Creek. The swell We were both ready was supposed to be to head back. I tried 4-5' which is usually various positions on mild, but the surf at my SUP, but it was Salmon Creek did hard to get not look all that comfortable for mild. For the rest of paddling and my the drive the water progress was very was shrouded in fog, slow. -

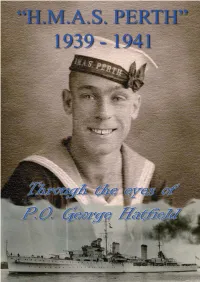

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

September 2006 Vol

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 ListeningListeningTHE AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2006 VOL. 29 No.4 PostPost The official journal of THE RETURNED & SERVICES LEAGUE OF AUSTRALIA POSTAGE PAID SURFACE WA Branch Incorporated • PO Box Y3023 Perth 6832 • Established 1920 AUSTRALIA MAIL Viet-NamViet-Nam –– 4040 YearsYears OnOn Battle of Long-Tan Page 9 90th Anniversary – Annual Report Page 11 The “official” commencement date for the increased Australian commitment, this commitment “A Tribute to Australian involvement in Viet-Nam is set at 23 grew to involve the Army, Navy and Air Force as well May 1962, the date on which the (then) as civilian support, such as medical / surgical aid Minister for External Affairs announced the teams, war correspondents and officially sponsored Australia’s decision to send military instructors to entertainers. Vietnam. The first Australian troops At its peak in 1968, the Australian commitment Involvement in committed to Viet-Nam arrived in Saigon on amounted to some 83,000 service men and women. 3rd August 1962. This group of advisers were A Government study in 1977 identified some 59,036 Troops complete mission Viet-Nam collectively known as the “Australian Army males and 484 females as having met its definition of and depart Camp Smitty Training Team” (AATTV). “Viet-Nam Veterans”. Page 15 1962 – 1972 As the conflict escalated, so did pressure for Continue Page 5. 2 THE LISTENING POST August/September 2006 FULLY LOADED DEALS DRIVE AWAY NO MORE TO PAY $41,623* Metallic paint (as depicted) $240 extra. (Price applies to ‘05 build models) * NISSAN X-TRAIL ST-S $ , PATHFINDER ST Manual 40th Anniversary Special Edition 27 336 2.5 TURBO DIESEL PETROL AUTOMATIC 7 SEAT • Powerful 2.5L DOHC engine • Dual SRS airbags • ABS brakes • 128kW of power/403nm Torque • 3,000kg towing capacity PLUS Free alloy wheels • Free sunroof • Free fog lamps (trailer with brakes)• Alloy wheels • 5 speed automatic FREE ALLOY WHEEL, POWER WINDOWS * $ DRIVE AWAY AND LUXURY SEAT TRIM. -

Perth Scuba News 09Jan10

Perth Scuba News www.perthscuba.com Tel: 08 9455 4448 The Manta Club Newsletter Page 1 Issue 91 9th January 2010 WHAT’S COMING UP? • Become a PADI Scuba God!!! Contact Lee on 9455 4448 or email [email protected] SEA & SEA DX-1200HD to discuss becoming a True hi-definition video in this compact camera makes the DX-1200HD a PADI Open Water Scuba Instructor. Find modern marvel. Choose to shoot photos or HD movies to share. out about getting a Camera features include: new job that you truly enjoy and is so much • High definition CCD with 12.19 effective megapixels and 3x optical zoom fun. lens. • Instructor • Features Sea & Sea mode, for brilliant underwater images. Development • Movie function up to 1280x720 pixels (HD video) at 30 frames/ Course begins second. 29th January 2010 $995 • Strong and durable build with a depth rating up to 45 metres. • Wide angle and close up lens accessories available - a big bonus! • Large monitor allows you to check the smallest details in your pictures as you take them. • Light and compact design allows you to use for marine sports in general, plus outdoors winter sports. We recommend this camera for all underwater digital photographers, from novice all the way up to advanced. IN STOCK NOW - COME IN & SEE THEM FOR YOURSELF! cruising past you? Perth Scuba can get you there with heaps of upcoming trips to a multitude of locations all over the world. Meet at Perth Scuba and we’ll show you some of the exciting places we’re visiting over the next 2 years. -

Volume 1 – FOC 2018

1 2 Table of Contents Surveying the Field II The Materiality of Roman Battle: Applying Conflict Archaeology Methods to the Roman World Joanne E. Ball…………………………………………………………………4 Methods in Conflict Archaeology: The Netherlands During the Napoleonic Era (1794-1815). Using Detector Finds to Shed Light on An Under-researched Period. Vincent van der Veen………………………………………………………..19 Musket Balls from the Boston Massacre: Are they Authentic? Dan Sivilich and Joel Bohy………………………………………………….31 Revisiting the US military ‘Levels of War’ Model as a Conceptual Tool in Conflict Archaeology: A Case Study of WW2 Landscapes in Normandy, France. David G Passmore, David Capps-Tunwell, Stephan Harrison………………44 A Decade of Community-Based Projects in the Pacific on WWII Conflict Sites Jennifer F. McKinnon and Toni L. Carrell…………………………………..61 Avocational Detectorists and Battlefield Research: Potential Data Biases Christopher T. Espenshade…………………………………………………..68 Maritime Conflict Archaeology: Battle of the Java Sea: Past and Present Conflicts Robert de Hoop and Martijn Manders……………………………………….75 A Battleship in the Wilderness: The Story of the Chippewa and Lake Ontario’s Forgotten War of 1812 Naval Shipyard* Timothy J. Abel……………………………………………………………...88 3 Surveying the Field II The Materiality of Roman Battle: Applying Conflict Archaeology Methodology to the Roman World. Joanne E. Ball Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7WZ [email protected] ABSTRACT Over the last three decades a growing number of Roman battle sites have been identified across western Europe. Archaeological study of these sites has adapted methodologies developed from the Little Bighorn project onward to the material characteristics of Roman battle, and continue to be refined. Difficulties have been encountered in locating sites within a landscape, due to inadequacies in the historical record. -

Recreational Fishing for Rock Lobster

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Rock lobster Recreational fishing guide 2020/21 A current licence is required to fish for any species of rock lobster Please note: • Fishing is permitted year-round. • Pot rope requirements apply when fishing with a combined pot line and float rig length longer than 20 metres. • A maximum of 2 floats may be attached to your pot. • Female setose lobsters may be taken. • Rock lobster tails (shell on) may be kept at your principal place of residence. Published August 2020 Contents Fish for the future ........................................1 Recreational fishing rules ...........................2 Licences ...................................................... 2 Fishing season and times ............................ 2 Legal size limits for taking lobsters ............. 3 Western and tropical rock lobster ................ 4 Southern rock lobster .................................. 4 Statewide catch limits ................................. 4 Fishing for lobsters ...................................... 5 Pot specifications ......................................... 7 Rope coiling ............................................... 12 Sea lion exclusion devices (SLEDs) ......... 13 Plastic bait bands ...................................... 13 Totally protected lobsters ........................... 14 Identifying berried and tarspot lobsters ..... 15 Lobsters you keep......................................16 Marine conservation areas ........................17 Other rock lobster fishing closures ........... -

Thursday 19Th February 1942 by Dennis J Weatherall JP TM AFAITT(L) LSM – Volunteer Researcher

OCCASIONAL PAPER 74 Call the Hands Issue No. 39 March 2020 World War 2 Arrived on the Australian Mainland: Thursday 19th February 1942 By Dennis J Weatherall JP TM AFAITT(L) LSM – Volunteer Researcher Dennis Weatherall attended the recent 78th Anniversary of the Bombing of Darwin, also known as the “Battle of Darwin”, by Japanese Imperial Forces on Thursday 19th February 1942. The air raid siren sounded at exactly 09:58 - war had arrived in Australia. He asks why more Australians don’t know about the continuous attacks that started on that day and continued until 12th November 1943 - some 21 months. In this paper Dennis provides and overview of the attacks and naval losses in more detail. Darwin, has changed much since my last visit some 38 years ago and it is dramatically different to the Darwin of 1942 which bore the brunt of the first ever attack by a foreign power on Australian soil. Why didn’t we know they were coming? Was our intelligence so bad or were we too complacent in 1942? The Government of the day had anticipated the Japanese would push south but “when” was the big question. Evacuations of civilians had already started by February 1942. On the morning of the fateful day there were many ships, both Naval and Merchant men, in the Port of Darwin along with a QANTAS flying boat “Camilla” and three Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats of the USN, when 188 Japanese aircraft of various types, 36 Zero fighters, 71 dive bombers and 81 medium attack bombers commenced their first raid. -

US, Australian, Indonesian Navies Honor USS Houston, HMAS Perth

Volume 72, Issue 3 • December, 2014 “Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast” Newsletter of the U.S.S. Houston CA-30 Survivors Association and Next Generations Now Hear This! US, Australian, Indonesian Navies Honor Association Address: USS Houston, HMAS Perth c/o John K. Schwarz, Executive Director 2500 Clarendon Blvd., Apt. 121 Arlington, VA 22201 Association Phone Number: 703-867-0142 Address for Tax Deductible Contributions: USS Houston Survivors Association c/o Pam Foster, Treasurer 370 Lilac Lane, Lincoln, CA 95648 (Please specify which fund – General or Scholarship) Association Email Contact: [email protected] Association Founded 1946: by Otto and Trudy Schwarz (Oct. 14, 2014) Naval officers from Australia, Indonesia and the United States participate in a wreath-laying ceremony aboard the submarine tender USS Frank Cable (AS 40) in honor In This Issue… of the crews of the U.S. Navy heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA 30) and the Royal Australian Navy light cruiser HMAS Perth (D29). Wreath-laying Ceremony / 1, 2 . Vice Admiral Swift’s Selfie / 2 By Mass Communication Specialist 2/c In This Issue…cont. Brian T. Glunt, USS Frank Cable . Desk of Executive Director / 3 . Howard Brooks’ Birthday / 14 Public Affairs . Hostick Memorial Service / 4 . Photo Collection / 15 . CL-81 Reunion / 4 . 2015 Reunion Schedule / 16, 17 Sailors and Military Sealift . Bill Ingram Honored / 5 . Sales Items / 18 Command (MSC) civilian mariners . Basil Bunyard’s New Jacket / 5 . Board of Managers / 19 assigned to the submarine tender . You Shop, Amazon Gives / 5 . Welcome Aboard / 19 USS Frank Cable (AS 40), along . David Flynn’s Funeral / 6 . -

Additional Historic Information the Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish

USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum Additional Historic Information The Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish AMERICA STRIKES BACK The Doolittle Raid of April 18, 1942 was the first U.S. air raid to strike the Japanese home islands during WWII. The mission is notable in that it was the only operation in which U.S. Army Air Forces bombers were launched from an aircraft carrier into combat. The raid demonstrated how vulnerable the Japanese home islands were to air attack just four months after their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. While the damage inflicted was slight, the raid significantly boosted American morale while setting in motion a chain of Japanese military events that were disastrous for their long-term war effort. Planning & Preparation Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Roosevelt tasked senior U.S. military commanders with finding a suitable response to assuage the public outrage. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a difficult assignment. The Army Air Forces had no bases in Asia close enough to allow their bombers to attack Japan. At the same time, the Navy had no airplanes with the range and munitions capacity to do meaningful damage without risking the few ships left in the Pacific Fleet. In early January of 1942, Captain Francis Low1, a submariner on CNO Admiral Ernest King’s staff, visited Norfolk, VA to review the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, USS Hornet CV-8. During this visit, he realized that Army medium-range bombers might be successfully launched from an aircraft carrier. -

Legal Status of Warship Wrecks from World War Ii in Indonesian Territorial Waters (Incident of H.M.A.S

LEGAL STATUS OF WARSHIP WRECKS FROM WORLD WAR II IN INDONESIAN TERRITORIAL WATERS (INCIDENT OF H.M.A.S. PERTH COMMERCIAL SALVAGING) Senada Meskin Post Graduate Student, Australian National University Canberra Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Second World War was one of the most devastating experiences that World as a whole had to endure. The war left so many issues unhandled, one such issue is the theme of this thesis, and that is to analyze legal regime that is governing sunken warships. Status of warship still in service is protected by international law and national law of the flag State, stipulating that warships are entitled to sovereign immunity. The question arises whether or not such sovereign immunity status follows warship wreck? Contemporary international law regulates very little considering ”sovereign wrecks‘, but customary international law, municipal court decisions and State practices are addressing issues quite profoundly, stating that even the warship is no longer in service it is still entitled to sovereign immunity status. HMAS Perth is Australian owned warship whose wreck current location is within Indonesian Territorial Sea. Recent reports show that commercial salvaging has been done, provoking outrage amongst surviving HMAS 3erth‘s naval personnel and Australian historians. In order to acquire clear stand point on issue of Sovereign :recks legal status, especially of +0AS 3erth‘s wreck, an in-depth analysis of legal material is necessary. Keywords: Territorial Waters, Warship, Warship Wreck, Salvage World War2, and Indonesia, which waters, I. INTRODUCTION many countries used as passage, had its part Sea going vessels has been used as a as well. -

1 of 7 Three Ships Named USS Marblehead Since the Latter Part Of

Three Ships named USS Marblehead The 1st Marblehead Since the latter part of the 19th century, cruisers in the United States Navy have carried the names of U.S. cities. Three ships have been named after Marblehead, MA, the birthplace of the U.S. Navy, and all three had distinguished careers. The 1st Marblehead. The first Marblehead was not a cruiser, however. She Source: Wikipedia.com was an Unadilla-class gunboat designed not for ship-to-ship warfare but for bombardment of coastal targets and blockade runners. Launched in 1861, she served the Union during the American Civil War. First assigned to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, she took part in operations along the York and Pamunkey Rivers in Virginia. On 1 MAY 1862, she shelled Confederate positions at Yorktown in support of General George McClellan's drive up the peninsula toward Richmond. In an unusual engagement, this Marblehead was docked in Pamunkey River when Confederate cavalry commander Jeb Stuart ordered an attack on the docked ship. Discovered by Union sailors and marines, who opened fire, the Confederate horse artillery under Major John Pelham unlimbered his guns and fired on Marblehead. The bluecoats were called back aboard and as the ship got under way Pelham's guns raced the ship, firing at it as long as the horse can keep up with it. The Marblehead escaped. Reassigned to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, she commenced patrols off the southern east coast in search of Confederate vessels. With the single turreted, coastal monitor Passaic, in early-FEB 1863, she reconnoitered Georgia’s Wilmington River in an unsuccessful attempt to locate the ironclad ram CSS Atlanta.