1 the Battle for CRETE by Clive Sharplin (Associate Member)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

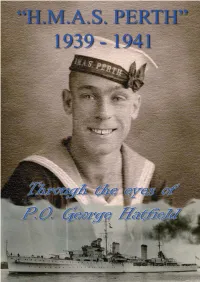

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

On Our Doorstep Parts 1 and 2

ON 0UR DOORSTEP I MEMORIAM THE SECOD WORLD WAR 1939 to 1945 HOW THOSE LIVIG I SOME OF THE PARISHES SOUTH OF COLCHESTER, WERE AFFECTED BY WORLD WAR 2 Compiled by E. J. Sparrow Page 1 of 156 ON 0UR DOORSTEP FOREWORD This is a sequel to the book “IF YOU SHED A TEAR” which dealt exclusively with the casualties in World War 1 from a dozen coastal villages on the orth Essex coast between the Colne and Blackwater. The villages involved are~: Abberton, Langenhoe, Fingringhoe, Rowhedge, Peldon: Little and Great Wigborough: Salcott: Tollesbury: Tolleshunt D’Arcy: Tolleshunt Knights and Tolleshunt Major This likewise is a community effort by the families, friends and neighbours of the Fallen so that they may be remembered. In this volume we cover men from the same villages in World War 2, who took up the challenge of this new threat .World War 2 was much closer to home. The German airfields were only 60 miles away and the villages were on the direct flight path to London. As a result our losses include a number of men, who did not serve in uniform but were at sea with the fishing fleet, or the Merchant avy. These men were lost with the vessels operating in what was known as “Bomb Alley” which also took a toll on the Royal avy’s patrol craft, who shepherded convoys up the east coast with its threats from: - mines, dive bombers, e- boats and destroyers. The book is broken into 4 sections dealing with: - The war at sea: the land warfare: the war in the air & on the Home Front THEY WILL OLY DIE IF THEY ARE FORGOTTE. -

September 2006 Vol

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 ListeningListeningTHE AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2006 VOL. 29 No.4 PostPost The official journal of THE RETURNED & SERVICES LEAGUE OF AUSTRALIA POSTAGE PAID SURFACE WA Branch Incorporated • PO Box Y3023 Perth 6832 • Established 1920 AUSTRALIA MAIL Viet-NamViet-Nam –– 4040 YearsYears OnOn Battle of Long-Tan Page 9 90th Anniversary – Annual Report Page 11 The “official” commencement date for the increased Australian commitment, this commitment “A Tribute to Australian involvement in Viet-Nam is set at 23 grew to involve the Army, Navy and Air Force as well May 1962, the date on which the (then) as civilian support, such as medical / surgical aid Minister for External Affairs announced the teams, war correspondents and officially sponsored Australia’s decision to send military instructors to entertainers. Vietnam. The first Australian troops At its peak in 1968, the Australian commitment Involvement in committed to Viet-Nam arrived in Saigon on amounted to some 83,000 service men and women. 3rd August 1962. This group of advisers were A Government study in 1977 identified some 59,036 Troops complete mission Viet-Nam collectively known as the “Australian Army males and 484 females as having met its definition of and depart Camp Smitty Training Team” (AATTV). “Viet-Nam Veterans”. Page 15 1962 – 1972 As the conflict escalated, so did pressure for Continue Page 5. 2 THE LISTENING POST August/September 2006 FULLY LOADED DEALS DRIVE AWAY NO MORE TO PAY $41,623* Metallic paint (as depicted) $240 extra. (Price applies to ‘05 build models) * NISSAN X-TRAIL ST-S $ , PATHFINDER ST Manual 40th Anniversary Special Edition 27 336 2.5 TURBO DIESEL PETROL AUTOMATIC 7 SEAT • Powerful 2.5L DOHC engine • Dual SRS airbags • ABS brakes • 128kW of power/403nm Torque • 3,000kg towing capacity PLUS Free alloy wheels • Free sunroof • Free fog lamps (trailer with brakes)• Alloy wheels • 5 speed automatic FREE ALLOY WHEEL, POWER WINDOWS * $ DRIVE AWAY AND LUXURY SEAT TRIM. -

US, Australian, Indonesian Navies Honor USS Houston, HMAS Perth

Volume 72, Issue 3 • December, 2014 “Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast” Newsletter of the U.S.S. Houston CA-30 Survivors Association and Next Generations Now Hear This! US, Australian, Indonesian Navies Honor Association Address: USS Houston, HMAS Perth c/o John K. Schwarz, Executive Director 2500 Clarendon Blvd., Apt. 121 Arlington, VA 22201 Association Phone Number: 703-867-0142 Address for Tax Deductible Contributions: USS Houston Survivors Association c/o Pam Foster, Treasurer 370 Lilac Lane, Lincoln, CA 95648 (Please specify which fund – General or Scholarship) Association Email Contact: [email protected] Association Founded 1946: by Otto and Trudy Schwarz (Oct. 14, 2014) Naval officers from Australia, Indonesia and the United States participate in a wreath-laying ceremony aboard the submarine tender USS Frank Cable (AS 40) in honor In This Issue… of the crews of the U.S. Navy heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA 30) and the Royal Australian Navy light cruiser HMAS Perth (D29). Wreath-laying Ceremony / 1, 2 . Vice Admiral Swift’s Selfie / 2 By Mass Communication Specialist 2/c In This Issue…cont. Brian T. Glunt, USS Frank Cable . Desk of Executive Director / 3 . Howard Brooks’ Birthday / 14 Public Affairs . Hostick Memorial Service / 4 . Photo Collection / 15 . CL-81 Reunion / 4 . 2015 Reunion Schedule / 16, 17 Sailors and Military Sealift . Bill Ingram Honored / 5 . Sales Items / 18 Command (MSC) civilian mariners . Basil Bunyard’s New Jacket / 5 . Board of Managers / 19 assigned to the submarine tender . You Shop, Amazon Gives / 5 . Welcome Aboard / 19 USS Frank Cable (AS 40), along . David Flynn’s Funeral / 6 . -

Legal Status of Warship Wrecks from World War Ii in Indonesian Territorial Waters (Incident of H.M.A.S

LEGAL STATUS OF WARSHIP WRECKS FROM WORLD WAR II IN INDONESIAN TERRITORIAL WATERS (INCIDENT OF H.M.A.S. PERTH COMMERCIAL SALVAGING) Senada Meskin Post Graduate Student, Australian National University Canberra Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Second World War was one of the most devastating experiences that World as a whole had to endure. The war left so many issues unhandled, one such issue is the theme of this thesis, and that is to analyze legal regime that is governing sunken warships. Status of warship still in service is protected by international law and national law of the flag State, stipulating that warships are entitled to sovereign immunity. The question arises whether or not such sovereign immunity status follows warship wreck? Contemporary international law regulates very little considering ”sovereign wrecks‘, but customary international law, municipal court decisions and State practices are addressing issues quite profoundly, stating that even the warship is no longer in service it is still entitled to sovereign immunity status. HMAS Perth is Australian owned warship whose wreck current location is within Indonesian Territorial Sea. Recent reports show that commercial salvaging has been done, provoking outrage amongst surviving HMAS 3erth‘s naval personnel and Australian historians. In order to acquire clear stand point on issue of Sovereign :recks legal status, especially of +0AS 3erth‘s wreck, an in-depth analysis of legal material is necessary. Keywords: Territorial Waters, Warship, Warship Wreck, Salvage World War2, and Indonesia, which waters, I. INTRODUCTION many countries used as passage, had its part Sea going vessels has been used as a as well. -

Issue 46, October 2020

From the President Welcome to this 46th edition of Call the Hands. As always, we are pleased to present a wide cross section of stories and draw attention to some most interesting audio and video recordings. Don’t miss the links to a short description by Lieutenant Commander Henry Stoker of AE2’s 1915 passage through the Dardanelles strait and the snippets of life in HMAS Australia (II) in 1948. In a similar vein, those with an interest in HMAS Cerberus should not miss the link to aerial footage of the extensive building works undertaken in Cerberus in recent years. In its 100th anniversary year HMAS Cerberus is well equipped for current and future high trainee throughputs. Highlighted are two remarkable people; Able Seaman Moss Berryman the last member of the Operation Jaywick operatives and Surgeon Lieutenant Commander Samuel Stening, a HMAS Perth survivor and POW. Links to their remarkable stories are worthy of attention. Occasional Paper 91 provides detailed insight into strategic and operational level decisions concerning the employment of the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Navy’s China Fleet and South Atlantic Squadron in pursuit of the German East Asia Squadron during the early months of World War One. It is a story of bungled and poor strategic decision making on the part of the First Sea Lord and Admiralty. The consequences of this disjointed strategy, wasted time and not allowing Admiral Sir George Patey freedom of action in his flagship HMAS Australia, to pursue the German Squadron were significant. Occasional Paper 92 addresses the matter of the award of the first Royal Australian Navy Victoria Cross and other forms of recognition for Ordinary Seaman Edward “Teddy” Sheean. -

CHAPTER 1 5 ABDA and ANZA CN the Second World

CHAPTER 1 5 ABDA AND ANZA C N the second world war the democracies fought at an initial disadvan- Itage, though possessing much greater resources than their enemies . Britain and the United States had embarked on accelerated rearmamen t programs in 1938, the naval projects including battleships and aircraf t carriers ; but this was a delayed start compared with that of Germany an d Japan. Preparing for munitions production for total war, finding out wha t weapons to make, and their perfection into prototypes for mass produc- tion, takes in time upwards of two decades . After this preparation period, a mass production on a nation-wide scale is at least a four-years' task in which "the first year yields nothing ; the second very little ; the third a lot and the fourth a flood" .' When Japan struck in December 1941, Britai n and the British Commonwealth had been at war for more than two years . During that time they had to a large extent changed over to a war economy and increasingly brought reserve strength into play . Indeed, in 1940, 1941 and 1942, British production of aircraft, tanks, trucks, self-propelled gun s and other materials of war, exceeded Germany 's. This was partly due to Britain's wartime economic mobilisation, and partly to the fact that Ger- many had not planned for a long war. Having achieved easy victories b y overwhelming unmobilised enemies with well-organised forces and accumu- lated stocks of munitions and materials, the Germans allowed over- confidence to prevent them from broadening the base of their econom y to match the mounting economic mobilisation of Britain . -

World War Two

HMS CONWAY – WORLD WAR TWO COMPANIONS OF THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER Wing Commander Robert Swinton Allen (29/30) DFC RAFO LG 25263 dated 02/09/1941; DSO awarded in connection with bombing raids on Brest, Pelice and Cherburg recognising the bravery, determination and resource displayed by the leader and air crews. Wing Cdr R S Allen DSO, DFC* RAF retired at his own request in March 1956. Interesting site mentioning Allen and with photograph at: http://cranstonmilitaryprints.com/hampden/ww2/aviation/prints.htm Captain Jack Grant Bickford (10/13) DSC RN LG 34925 dated 16/08/1940; DSO awarded “for good services in the withdrawal of Allied troops from the beaches at Dunkirk” Captain Bickford commanded HMS Express and was Captain (D) 20th Destroyer (Mine- laying) Flotilla from August 1939; he was mortally wounded in action when Express herself was mined and attacked by Enemy aircraft during operations off the Dutch/Belgian coast on 31/08/1940, subsequently succumbing to his wounds in hospital on 10/09/40. He was buried at sea. Commodore Denis Arthur Casey (02/04) CBE DSC RD RNR LG 35369 dated 21/07/42; Casey was the Commodore of Convoy PQ10 from Murmansk and was awarded the DSO “for bravery seamanship and resolution in bringing a convoy from Murmansk in the face of relentless and determined attacks by Enemy U-Boats and aircraft”. Casey won his DSC in World War One for service in submarines; he became the RNR ADC to the King in 1944 and was noted as being Commodore Master, RMS Andes 1948/49. -

The World Cruise the Complete Story of Hms Ajax

THE WORLD CRUISE THE COMPLETE STORY OF H.M.S. AJAX DURING 1975-76 Author believed to be CRS (W) Fox We sailed out of Plymouth Sound on the morning of July the 22nd to the sound of "When will I see you again" by the "Three Degrees" playing on the Jimmy young Show. I suppose that the wife who requested that record for the Eighth Frigate Squadron was not presented with a copy of our 'Longcast'. We thank you for your kind thought. We left in company with H.M.S. Berwick and that afternoon we were hard at work carrying out anti-submarine exercises with the Submarine H.M.S/M Otter and R.A.F. Nimrod. At 0130 the following morning, we rendezvous'd with the remainder of the Deployment Group - H.M.S.'s Glamorgan (Flying the Flag of Flag Officer Second Flotilla), Plymouth, Llandaff, Rothesay and R.F.A.'s Gold Rover, Tarbatness and Tidespring. Immediately the Group were busy working together fighting off 'attacks' by Otter. As we headed South, Admiral Lewin, the then Commander-in-Chief Fleet, sent the following message to the Task Group: "The progress of your circumnavigation will be watched with envy. You carry the reputation of the Fleet with you. I am confident that it is in good hands and that you will remind the people of many countries of the continuing professionalism and courtesy of the Royal Navy. Work hard, have fun, and enjoy the comradship of your impressive Group. Bon Voyage." From the Southwest Approaches we proceeded to Cape Finisterre carrying out inter-ship exercises. -

Battle of Cape Matapan HMS AJAX and the Battle of Cape Matapan

Battle of Cape Matapan HMS AJAX and the Battle of Cape Matapan: 28th – 29th March 1941 By Clive Sharplin (Associate Member) The sea fight of the Second World War known as the “Battle of Matapan” was actually the second of that name to occur in naval history. The first occurred on 19th July 1717 when a mixed force of fifty-seven ships and galleys, Spanish, Portuguese, Venetian and Papal were attacked off Cape Matapan by a Turkish squadron of about the same size. After a fierce fight with losses on both sides the Turks withdrew. The ship HMS Ajax was a Leander Class light cruiser, the seventh ship to bear the name, relatively young having been launched in 1934, first commissioned in 1935. Displacing 9,563tons fully laden, her main armament consisted of 8 x 6”guns mounted in pairs over four turrets with 8 x 21 “ torpedo tubes in two quadruple mountings, steam turbine driven, with a wartime crew of 680. After participating in the first major sea battle of the second World War, the Battle of the River Plate in December 1939 and defeating the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee she returned to Chatham Dockyard for a 7 month long repair and refit during which my Father, Bob, joined her on 10th February 1940 as a Petty Officer Mechanician, he was to be a crew member for more` than a year until September 1941 when he was drafted to the battleship Valiant, thus enduring one of the Royal Navy’s most hostile periods. Ajax emerged back into the fleet on September 30th 1940 being deployed to the 7th Cruiser Squadron in the Mediterranean. -

CALL the HANDS NHSA DIGITAL NEWSLETTER Issue No.20 June 2018

CALL THE HANDS NHSA DIGITAL NEWSLETTER Issue No.20 June 2018 From the President In the absence of our President this month, it is my pleasure to commend to you the June edition of Call the Hands and accompanying Occasional Papers. In addition to the historical stories we are reminded that history is being made on a regular basis by the Royal Australian Navy with the advent of our new Air Warfare destroyers and the introduction of cutting edge capabilities such as the 'Cooperative Engagement' linking technology recently trialled by HMAS Hobart and HMAS Brisbane. The biography of Leading Cook Francis Bassett ‘Dick’ Emms provides us with insight into not just his distinguished service but the shape of the Fleet, it employment and sailors postings during the interwar years. Several interesting podcasts have come to notice in the past month. Life on the Line has interviewed a number of distinguished former Naval Officers which are well worth listening to. They can be accessed through the website www.lifeonlinepodcast.com. Stan Nicholls at 93 is very interested in Naval History and his son has recorded his comments on service in three of the four HMAS Sydney’s that have served the Australian Navy. This video is probably Stan’s last and can be found on YouTube at HMAS Sydney by Stan Nicholls. As usual, we are very grateful to members and subscribers for this type of feedback. I would also remind all our readers that our website and Facebook page will keep you in touch with a range of naval historical information. -

Cruiser: the Life and Loss of HMAS Perth and Her Crew Free Ebook

FREECRUISER: THE LIFE AND LOSS OF HMAS PERTH AND HER CREW EBOOK Mike Carlton | 720 pages | 01 Dec 2011 | Random House Australia | 9781864711332 | English | North Sydney, Australia HMAS Perth (D29) - Wikipedia The lowest-priced item in unused and unworn condition with absolutely no signs of wear. The item may be missing the original packaging such as the original box or bag or tags or in the original packaging but not sealed. The item may be a factory second or a new, unused item with defects or irregularities. See details for description of any imperfections. Some amazing history. Verified purchase: Yes Condition: Pre-owned. Skip to main content. About this product. Make an offer:. Stock photo. New other : Lowest price The lowest-priced item in unused and unworn condition with absolutely no signs of wear. Excellent condition. There is an inscription on the front facing page as shown in photo, but overall very good like new. Most were young - many were still teenagers - from cities and towns, villages and farms across the nation. See all 2 new other listings. Buy It Now. Add to cart. They were Cruiser: The Life and Loss of HMAS Perth and Her Crew lost in a hurricane in the Atlantic. In the Mediterranean in they were bombed by the Luftwaffe and the Italian Air Force for months on end until; ultimately, during the disastrous evacuation of the Australian army from Crete, their ship took a direct hit and thirteen men were killed. Off the. Firing until her ammunition literally ran out, she was sunk with the loss of of her crew, including her much-loved captain and the Royal Australian Navy's finest fighting sailor, 'Hardover' Hec Waller.