The Rising Dragon’S Environmental Disaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

Report on Shanghai Water Projects

Consulate General of Switzerland in Shanghai Commercial Section ISSUE NO.4 July 2003 Report on Shanghai Water Projects ‘A glass of water with half a glass of dirt’ was the vivid picture of the quality of drinking water in Shanghai some 25 years ago. People could still clearly remember the strange taste of the water at that time. Half a century’s industrialisation not only led to Shanghai’s fast development, but also to serious environmental problems. As the Chinese saying goes, a city with a river running through it is a city full of life. But this cannot be applied to Shanghai. Having two heavily polluted rivers running across the city, the Huangpu River and the Suzhou Creek, Shanghai has to deal with two problematic water currants. Back to even five years ago, walking along the famous Bund area was not a pleasant experience because of the bad smell emanating from the Huangpu River. For people living close to the Suzhou Creek, the situation was even worse. People had to keep windows closed day and night to avoid the foul smell from the water in the neighbourhood. Instead of being green and clear, the Creek was black and opaque, full of sewage. The drinking water for urban residents is seriously polluted as it comes mainly from outlying sections of these two rivers - the upper stretch of the Huangpu River near the Songpu Bridge in Minhang District, and the river mouth where the Yangtze River merges with the East China Sea. Faced with the threat of worsening water pollution, and demands of meeting international environmental standards, the Shanghai government decided to adopt measures for improving the environmental situation in the city. -

The Current Status of Environmental Criteria for Hydropower Development in the Mekong Region a Literature Compilation

The Current Status of Environmental Criteria for Hydropower Development in the Mekong Region A Literature Compilation by Peter King, Jeremy Bird, Lawrence Haas ` March 2007 Coordination and Editing: WWF/Marc Goichot WWF–Living Mekong Programme P.O. Box 7871. House. 39. Unit 05 Ban Saylom, Vientiane, Lao PDR Email: [email protected] Design and Layout: WWF/Noy Promsouvanh Cover photos: MRC/Jim Holmes, MRC/Garris on Photography, MRC/Virginia Adamson. Cover illustration: Phanavanh Anoulack The opinions and interpretations expressed within are those of authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, Mekong River Commission Secretariat and WWF. The Current Status of Environmental Criteria for Hydropower Development in the Mekong Region: A literature compilation Foreword Population growth, economic development, and associated increases in personal wealth are causing growth in electricity demand across the Greater Mekong region, if not uniformly within the different countries, still at an overall rapid rate for the region as a whole. Different sets of options are open to meet this demand – each with unique advantages and disadvantages - all of which become entangled in the complex play of diverging priorities supported by different interest groups. In the mean time, the recent recognition of the role of human activities on climate change is leading to rethinking of the entire energy sector. As a result, a complex paradigm lies in front of decision makers, touching on crucial issues such as global -

INDIAN & WORLD GEOGRAPHY ASTRONOMY 1. What Is the Difference Between Asteroids and Comets?

INDIAN & WORLD GEOGRAPHY ASTRONOMY 1. What is the difference between asteroids and comets? (2011) 1. Asteroids are small rocky planetoids, while comet are formed of frozen gases held together by rocky and metallic material. 2. Asteroids are found mostly between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars, while comets are found mostly between Venus and Mercury. 3. Comets show a perceptible glowing tail, while asteroids do not. Which of the statements given above is/are correct? (a) 1 and 2 (b) 1 and 3 (c) 3 (d) 1,2 and 3 Ans: B The biggest difference between comets and asteroids is what they are made of. While asteroids consist of metals and rocky material, comets are made up of ice, dust, rocky materials and organic compounds. When comets get closer to the Sun, they lose material with each orbit because some of their ice melts and vaporizes. Asteroids typically remain solid, even when near the Sun. Right now, the majority of asteroids reside in the asteroid belt, a region between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter which may hold millions of space rocks of varying sizes. On the other hand, the majority of comets are in the farthest reaches of our Solar System: either 1. in the Kuiper Belt — a region just outside the orbit of the dwarf planet Pluto that may have millions of icy comets (as well as many icy dwarf planets like Pluto and Eris); or 2. the Oort Cloud, a region where trillions of comets may circle the Sun at huge distances of up to 20 trillion kilometers (13 trillion miles). -

Bacteria in Urban River Networks*

Environmental Pollution 254 (2019) 112998 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environmental Pollution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envpol Dynamics and environmental importance of anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) bacteria in urban river networks* * Yanling Zheng a, b, c, Lijun Hou c, , Min Liu a, b, Guoyu Yin a, b a School of Geographic Sciences, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200241, China b Key Laboratory of Geographic Information Science (Ministry of Education), East China Normal University, Shanghai 200241, China c State Key Laboratory of Estuarine and Coastal Research, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200241, China article info abstract Article history: Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) is recognized as an important bioprocess for nitrogen Received 18 May 2019 removal, yet little is known about the associated microbial communities in urban river networks which Received in revised form are intensively disturbed by human activity. In the present study, we investigated the community 3 July 2019 composition and abundance of anammox bacteria in the urban river network of Shanghai, and explored Accepted 27 July 2019 their potential correlations with nitrogen removal activities and the environmental parameters. High Available online 2 August 2019 biodiversity of anammox bacteria was detected in the sediment of urban river networks, including Candidatus Brocadia, Scalindua, Jettenia, and Kuenenia. Anammox bacterial abundance ranged from Keywords: Â 6 Â 7 À1 Community dynamics 3.7 10 to 3.9 10 copies g dry sediment based on 16S rRNA gene, which was strongly correlated to < Nitrogen removal the metabolic activity of anammox bacteria (P 0.01). A strong linkage between anammox bacteria and Urban denitrifiers was detected (P < 0.05), implying a potential metabolic interdependence between these two þ River network nitrogen-removing microbes was existed in urban river networks. -

IOC/SOA International Workshop on Coastal Megacities; IOC/SOA

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Workshop Report No. 166 IOC-SOA International Workshop on Coastal Megacities:Challenges of Growing Urbanisation Coastal Areas Organised in co-operation with the International Ocean Institute (IOI), Malta Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China 27-30 September 1999 UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Workshop Report No. 166 IOC-SOA International Workshop on Coastal Megacities:Challenges of Growing Urbanisation of the World’s Coastal Areas Organised in co-operation with the International Ocean Institute (IOI), Malta Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China 27-30 September 1999 UNESCO 2000 IOC Workshop Report No. 166 Paris, August 2000 English only Abstract The International Workshop on Coastal Megacities,Challenges of Growing Urbanisation of the World’s Coastal was Areas held in Hangzhou, China, 27-30 September 1999, in co-operation with IOC (Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission) and SOA (State Oceanic Administration, China), and with the collaboration of the International Ocean Institute. The workshop focused on the rapid development of coastal megacities and the relating environmental problems. Urban political leaders/officials in charge of city planning and coastal management from worldwide megacities (Jakarta, Shanghai, Buenos Aires, Lagos, Madras) were brought together with natural and social scientists working at the land-sea interface, and with national and local authorities concerned with coastal and sea management. Representatives from international organizations also contributed -

A Critical Review of the Appearance of Black-Odorous Waterbodies in China and Treatment Methods

Journal of Hazardous Materials xxx (xxxx) xxxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Hazardous Materials journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhazmat A critical review of the appearance of black-odorous waterbodies in China and treatment methods Jingxin Caoa,b,1, Qin Sunc,1, Donghua Zhaod, Meiying Xue, Qiushi Shena, Dan Wangd, Yan Wanga,f, Shiming Dinga,* a State Key Laboratory of Lake Science and Environment, Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China b University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China c Key Laboratory of Integrated Regulation and Resource Development on Shallow Lakes, Ministry of Education, College of Environment, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, China d Shanghai Waterway Engineering Design and Consulting Co., Ltd., Shanghai 200120, China e Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Microbial Culture Collection and Application, Guangdong Institute of Microbiology, Guangzhou 510070, China f Nanjing Easysensor Environmental Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210018, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Editor: R Teresa Black-odorous rivers and lakes are a serious environmental problem and are frequently reported in China. Keywords: Despite this, there have been no comprehensive in-depth reviews of black-odorous water formation mechanisms, Water quality assessment contributing factors and potential treatment technologies. Elements such as S, C and N play an important role in Metal sulfides the biogeochemical cycle of black-odorous waterbodies, with water blackening caused by metal sulfides such as Volatile organic sulfur compounds iron sulfide (FeS) and manganese sulfide (MnS). Volatile substances such as volatile organic sulfur compounds Sediment remediation (VOSCs) are the main contributors of odor. Microorganisms such as sulfate reducing bacteria (SRB), Bacteroidetes Bio-Ecological and Proteobacteria play important roles in blackening and odor formation processes. -

Making Cities Sustainable Through Rehabilitating Polluted Urban Rivers: Lessons from China and Other Developing Countries

Making cities sustainable through rehabilitating polluted urban rivers: Lessons from China and other developing countries I II Making cities sustainable through rehabilitating polluted urban rivers: Lessons from China and other developing countries Making cities sustainable through rehabilitating polluted urban rivers: Lessons from China and other developing countries Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), Tongji University, 2019 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) P.O. Box 30030 00100 Nairobi GPO KENYA Tel: 254-020-7623120 (Central Office) www.unhabitat.org Tongji University 1239 Siping Road, Shanghai, P.R. China Tel: +86-21-65982200 www.tongji.edu.cn HS Number: HS/006/19E ISBN Number: (Volume) 978-92-1-132832-5 DISCLAIMER: The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any county, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries regarding its economic system or degree of development. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the United Nations and its member states. Cover photos © Tongji University ACKNOWLEGDEMENTS The joint publication: Making cities sustainable through rehabilitating -

Luce Initiative on Asian Studies and the Environment

Luce Initiative on Asian Studies and the Environment Profiles of Grantee Institutions Table of Contents 4 Map of LIASE Grantees Grantee Profiles 6 ASIANetwork 10 Bard College 12 Beloit College 14 Carleton College 16 Centre College 18 The Claremont Colleges 22 Colorado College 24 Dickinson College 26 Earlham College 28 Eckerd College 30 Furman University 32 Hampshire College 34 Illinois College 36 Lawrence University 38 Oberlin College 40 Occidental College 42 St. Olaf College 44 Tri-Colleges Consortium 48 Trinity College 50 University of Puget Sound 52 Vassar College 54 Washington & Jefferson College 56 Whittier College 58 Willamette University 60 Topics of Focus NOTE Faculty designees attending the LIASE Conference in St. Paul, MN are denoted with an asterisk (*) on their respective institutional profile. A complete directory of LIASE websites, including links to individual faculty profiles, can be found at the LIASE Landing Page www.hluce.org/liaseresources.aspx. LIASE Grantees KEY Institution/Consortium, State (Exploration Grant Award Year) 4 2017 LIASE Conference LIASE Grantees LIASE Grantees 2017 LIASE Conference 5 CORE LIASE FACULTY Teodora O. Amoloza Professor of Sociology Illinois Wesleyan University Gary DeCoker Professor Emeritus of Education Ohio Wesleyan University Jack Harris* Professor of Sociology Hobart & William Smith Colleges Eriberto Lozada, Jr. Professor of Anthropology and Environmental Studies Davidson College PRIMARY GEOGRAPHIC SCOPE China: Yunnan Province Indonesia: Semarang PRIMARY ASIAN PARTNERS China: Yunnan University Indonesia: Soegijapranata Catholic University USA: Eckerd College, Warren Wilson College, ASIANetwork United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia c/o Ohio Wesleyan University Delaware, OH* STRATEGIES & PRACTICES Build institutional linkages between Exploration: Concluded American and Asian colleges and *At the time of the grant, ASIANetwork’s rotating secretariat was based at Illinois Wesleyan universities; Train faculty in service-learning University. -

A Spatial Improved-Knn-Based Flood Inundation Risk Framework for Urban Tourism Under Two Rainfall Scenarios

sustainability Article A Spatial Improved-kNN-Based Flood Inundation Risk Framework for Urban Tourism under Two Rainfall Scenarios Shuang Liu 1, Rui Liu 2,* and Nengzhi Tan 3 1 School of Tourism and Public Management, Huzhou Vocational and Technical College, Huzhou 313000, China; [email protected] 2 College of Geospatial Information Science and Technology, Capital Normal University, Beijing 100048, China 3 International College, Huzhou University, Huzhou 313000, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Urban tourism has been suffering socio-economic challenges from flood inundation risk (FIR) triggered by extraordinary rainfall under climate extremes. The evaluation of FIR is essential for mitigating economic losses, and even casualties. This study proposes an innovative spatial framework integrating improved k-nearest neighbor (kNN), remote sensing (RS), and geographic information system (GIS) to analyze FIR for tourism sites. Shanghai, China, was selected as a case study. Tempo-spatial factors, including climate, topography, drainage, vegetation, and soil, were selected to generate several flood-related gridded indicators as inputs into the evaluation framework. A likelihood of FIR was mapped to represent possible inundation for tourist sites under a moderate-heavy rainfall scenario and extreme rainfall scenario. The resultant map was verified by the maximum inundation extent merged by RS images and water bodies. The evaluation outcomes deliver the baseline and scientific information for urban planners and policymakers to take cost- Citation: Liu, S.; Liu, R.; Tan, N. A effective measures for decreasing and evading the pressure of FIR on the sustainable development of Spatial Improved-kNN-Based Flood urban tourism. The spatial improved-kNN-based framework provides an innovative, effective, and Inundation Risk Framework for easy-to-use approach to evaluate the risk for the tourism industry under climate change. -

Shanghai Shanghai

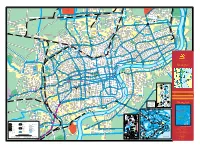

LONGHUA Wexi Rd AIRFIELD HUTAI RD DACHANG AIRFIELD PENGPU CHANGZHONG RD ZHAYIN RD Shiguang Rd YIXIAN RD • YOUDIAN Gongqing CHANGZHONG RD JIANGWAN Nursery Garden DONGTANG RD Rende Rd Xifong Rd Beijiao Station NONGMIN Rende Rd Rende Rd DACHANG (Northern Suburbs) Wanan Rd Wudong Rd Zhengli Rd SHANGHAI Zhengfu Rd HUTAI RD Institute of Nanda Rd Physical Minxing Rd Education West Chezhan Rd YIXIAN RD Wudong Rd SONGHU RD Xinshi Rd • No.1 Jiangwan Wuchuan Rd Tuberculosis Zhengmin Rd Stadium Panshan Rd Panshan Rd Shaojia Rd Wenshui Rd Jinian Rd No.2 Army Zhengyi Rd G Medical College d u JUNGONG RD R a g n n g Qilianshan Rd i XIANGYIN RD x y o u o Fudan Wanrong Rd a B h R HUTAI RD University t d r o LANHUA JIADING N Zhennan Rd DABAZI Pengjiang Rd HANDAN RD WUJIAOCHANG Shuidian Rd GONGHEXIN RD NORTH NINGGUO RD LUYANGQIAO Lingshi Rd Regal YUNGUANG Lantian D Shanghai R JiamusiZHONGNONG Rd Zhenda Rd N The Silk A Road W Guoshun Rd G N d Antu Rd Penglian Rd IA R TAOPU J SHENG u Songhuajiang Rd Guangzhong Rd o Shuidian Rd Dunhuan Rd Xinhu Rd Guoquan Rd k YE Guokang Rd g Chunjiang Rd n i Y GUANG Zhengben Rd DANING Quyang Rd ZHONG T HUTAI RD Chifeng Rd um e Lingshi Rd Institute of n Dongge Rd CHANGBAI West Taopu Rd d R Polytechnical Finance and Magnolia R d Minzhi Rd Easter Tiyuhui Rd Chifeng Rd yu d University N Economics g R To Nanjing Yutian Rd Jin nji o entral Ya r Zhangwu Rd C ast Institute of th QUYANG TONGJI KONGJIANG E Railway Tongji Zhidan Rd B d Machinery Zhennan Rd o Shanghai International University SIPING RD Yanji R Institute a D tral x R Studies -

Environmental Criteria for Hydropower Development in the Mekong Region a Literature Compilation

The Current Status of Environmental Criteria for Hydropower Development in the Mekong Region A Literature Compilation by Peter King, Jeremy Bird, Lawrence Haas Consultants Report to ADB, MRCS and WWF March 2007 Coordination and Editing: WWF/Marc Goichot WWF–Living Mekong Programme P.O. Box 7871. House. 39. Unit 05 Ban Saylom, Vientiane, Lao PDR Email: [email protected] Design and Layout: WWF/Noy Promsouvanh The opinions and interpretations expressed within are those of authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, Mekong River Commission Secretariat and WWF. The Current Status of Environmental Criteria for Hydropower Development in the Mekong Region: A litterature compilation Foreword Population growth, economic development, and associated increases in personal wealth are causing growth in electricity demand across the Greater Mekong region, if not uniformly within the different countries, still at an overall rapid rate for the region as a whole. Different sets of options are open to meet this demand – each with unique advantages and disadvantages - all of which become entangled in the complex play of diverging priorities supported by different interest groups. In the mean time, the recent recognition of the role of human activities on climate change is leading to rethinking of the entire energy sector. As a result, a complex paradigm lies in front of decision makers, touching on crucial issues such as global sustainability, national security/autonomy and key economic strategies. GMS electricity markets will obviously end up relying on a combination of solutions. A spatial mismatch between resources and demand brought the development of a regional power grid, allowing further movements within the region to share large urban centres, peak loads, and opening energy export channels to Eastern China and Malaysia; thus adding even more complexity to the overall situation, and shifting the thinking further from a national to a regional scale.