Thesis Hum 2012 Roosblad S.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zapiro : Tooning the Odds

12 Zapiro : Tooning The Odds Jonathan Shapiro, or Zapiro, is the editorial cartoonist for The Sowetan, the Mail & Guardian and the Sunday Times, and his work is a richly inventive daily commentary on the rocky evolution of South African democracy. Zapiro’s platforms in the the country’s two largest mass-market English-language newspapers, along with one of the most influential weeklies, give him influential access to a large share of the national reading public. He occupies this potent cultural stage with a dual voice: one that combines a persistent satirical assault on the seats of national and global power with an unambiguous commitment to the fundamentally optimistic “nation-building” narrative within South African political culture. Jeremy Cronin asserts that Zapiro "is developing a national lexicon, a visual, verbal and moral vocabulary that enables us to talk to each other, about each other."2 It might also be said that the lexicon he develops allows him to write a persistent dialogue between two intersecting tones within his own journalistic voice; that his cartoons collectively dramatise the tension between national cohesion and tangible progress on the one hand, and on the other hand the recurring danger of damage to the mutable and vulnerable social contract that underpins South African democracy. This chapter will outline Zapiro’s political and creative development, before identifying his major formal devices and discussing his treatment of some persistent themes in cartoons produced over the last two years. Lines of attack: Zapiro’s early work Zapiro’s current political outlook germinated during the State of Emergency years in the mid- eighties: he returned from military service with a fervent opposition to the apartheid state, became an organiser for the End Conscription Campaign, and turned his pen to struggle pamphlets. -

Objecting to Apartheid

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) OBJECTING TO APARTHEID: THE HISTORY OF THE END CONSCRIPTION CAMPAIGN By DAVID JONES Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the subject HISTORY At the UNIVERSITY OF FORT HARE SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR GARY MINKLEY JANUARY 2013 I, David Jones, student number 200603420, hereby declare that I am fully aware of the University of Fort Hare’s policy on plagiarism and I have taken every precaution to comply with the regulations. Signature…………………………………………………………… Abstract This dissertation explores the history of the End Conscription Campaign (ECC) and evaluates its contribution to the struggle against apartheid. The ECC mobilised white opposition to apartheid by focussing on the role of the military in perpetuating white rule. By identifying conscription as the price paid by white South Africans for their continued political dominance, the ECC discovered a point of resistance within apartheid discourse around which white opposition could converge. The ECC challenged the discursive constructs of apartheid on many levels, going beyond mere criticism to the active modeling of alternatives. It played an important role in countering the intense propaganda to which all white South Africans were subject to ensure their loyalty, and in revealing the true nature of the conflict in the country. It articulated the dis-ease experienced by many who were alienated by the dominant culture of conformity, sexism, racism and homophobia. By educating, challenging and empowering white citizens to question the role of the military and, increasingly, to resist conscription it weakened the apartheid state thus adding an important component to the many pressures brought to bear on it which, in their combination, resulted in its demise. -

The Rise of Fascist Politics in Post 1994 South Africa

Issue No.91 September 2008 The Rise of Fascistic Politics and How Judge Nicholson Handed Mbeki’s Head on a Platter to the Zuma Brigade APDUSA VIEWS P O BOX 8888 CUMBERWOOD 3235 1 e-mail: [email protected] website:www.apdusaviews.co.za ` THE RISE OF STALINIST/FASCIST POLITICS IN POST 1994 SOUTH AFRICA Introduction The hallmark of fascist politics is its extreme intolerance of views which contradict and differ. Fascist politics is unable to debate and discuss rationally and usually seeks to win an argument by violence or threats of violence. Exposure of its illegitimate activities is something which this brand of politicians cannot stand. You will usually find the fascist politician foaming and fulminating against opposition parties, branding them in the most hated terms, usually linking them with the hated former oppressive regimes. The press which has the power to transmit information and the skill to craft that information in the most effective manner and which has an army of investigators and writers called journalists and reporters comes in for special hatred. The press, more than others, is able to ferret out sensitive information, obtain confidential documents and has access to the most hidden secrets of people in power or positions of influence in the State, in politics, in industry or the church. Between the might of the state, the powerful groups and vested interests and the individual or civil society stand the law courts of the country. In a constitutional democracy, the law courts uphold the constitution. Through its judgements and orders, the law is applied and enforced. -

Mondi Foreword

The 8th Annual Newspaper Awards Wednesday, 6 May 2009 OBVIOUS IS OUR ENEMY JOURNALIST SA STORY FEATURE FREWIN, McCALL AND INSIDE OF THE YEAR 07 OF THE YEAR 08 PHOTOGRAPHY 19 JOEL MERVIS AWARD 24 Chris Collingridge’s winning photo in the category News MONDI Photography. The Star’s caption read: “Their faces contorted FOREWORD with hatred and contempt, these schoolchildren shout ONDI SHANDUKA NEWSPRINT IS and jeer and torment and delighted to once again play a central laugh at a woman refugee in Mrole in this great competition. For the Alexandra yesterday (14 May past eight years we have felt immense pride in 2008). This, perhaps of all the rewarding some of the country’s top journalists pictures that have come out for their outstanding contribution to society. of Alex this week, is the most Newspaper journalists have for centuries had disturbing. This is the lesson the power to influence public opinion and foster children have learnt from their elders… xenophobia, even if positive change in both small communities and they’ve never heard the word. great nations. Now, lying on a blanket on the Today I ask you to exert your powers of ground, and protected from persuasion to confront one of the most significant physical abuse by palings and challenges facing the planet: climate change. The barbed wire, the woman faces messages concerning what is required to combat the taunts in the one place she this phenomenon seem to have been received by thought she would escape a limited audience, locally at least. hatred… Alex police station.” This is illustrated by the fact that out of the 1.8-million tons of paper, magazine and board produced by South Africa annually, only one million tons is recycled. -

Four South African “Sunrises”, Four Cartoons, Four Eras and the Cyclical Nature of History

Historia, 63, 1, May 2018, pp 178-200 Four South African “sunrises”, four cartoons, four eras and the cyclical nature of history Lizette Rabe* Abstract History as having a cyclical nature has been accepted as theory since ancient times. According to this cyclical theory, events happen in recurring cycles, or, simply put, it is a matter of “history repeating itself”. This article examines four cartoons as an illustration of history as cyclical phenomenon in one metaphor that was used in four political cartoons that were published over just more than a century in South Africa. All four cartoons depict the metaphor of “a new dawn” or a “new sunrise”, although representing four different political eras in the country. As foundational point of departure, media history and media historiography is discussed, followed by cartoons and their development as editorial comment, after which follows a discussion of the use of metaphor in cartoons. The four cartoons, representing four political eras, are next presented, supplemented by brief biographies of the four cartoonists as further context. The cartoons, although representing different political eras in South Africa, are linked through the use of the sunrise metaphor, graphically illustrating history as being cyclical, or repeating itself. This article hopes to not only contribute to South African (media) history, but especially to stimulate cartoon studies, specifically from within a (media) historiographical framework. Key words: African nationalism; Afrikaner nationalism; cartoons; colonialism; imperialism; history; media history; South Africa. Opsomming Geskiedenis as synde siklies van aard word sedert die antieke tye as teorie aanvaar. Volgens hierdie sikliese teorie van die geskiedenis vind gebeurtenisse in siklusse plaas – ’n geval van “die geskiedenis herhaal homself”. -

CASE NUMBER: 60/2012 DATE of HEARING: 28 NOVEMBER 2012 JUDGMENT RELEASE DATE: 14 DECEMBER 2012 AGULHAS COMPLAINANT Vs Toptv

CASE NUMBER: 60/2012 DATE OF HEARING: 28 NOVEMBER 2012 JUDGMENT RELEASE DATE: 14 DECEMBER 2012 AGULHAS COMPLAINANT vs TopTV RESPONDENT TRIBUNAL: PROF JCW VAN ROOYEN SC (CHAIRPERSON) ADV B MMUSINYANE PROF S LÖTTER (CO-OPTED) The Complainant was invited but was unable to attend. For the Respondent: Mmabatho Kau, Channel Manager: Top ONE accompanied by Elvis Mudau, Programme Acceptance Officer. ________________________________________________________________________ Religion – satire not denigrating Jesus and not amounting to hate speech based on religion – Agulhas vs TopTV Case No: 60/2012(BCCSA). ______ __________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY The Registrar received a complaint concerning an insert in a news programme that, inter alia, consists of humorous and satirical perspectives of the news by way of puppets resembling the characters portrayed. Given the sensitive nature of one of the items, which satirised a recently discovered fourth-century Coptic text stating that Jesus had been married, the matter was referred to a Tribunal. The Tribunal held that the item did not qualify as hate speech based on religion, as defined in the Code. The Tribunal reasoned as follows: The TopTV news item does not denigrate Jesus. In fact, the Jesus puppet remains silent when his “wife” accuses him of poor wine-making, messing in the bathroom while trying to walk on water and that he should tell Mary Magdalene to stop calling him. The “wife” is portrayed as a modern-day woman who smokes and drinks; she is also a foolish, nagging wife. Nothing that she says in the programme is in any way impressive. It is in fact she who is the object of the satire. -

IDENTITY of PLACE, PLACES of IDENTITIES, CHANGE of PLACE NAMES in POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA Sylvain Guyot, Cecil Seethal

IDENTITY OF PLACE, PLACES OF IDENTITIES, CHANGE OF PLACE NAMES IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA Sylvain Guyot, Cecil Seethal To cite this version: Sylvain Guyot, Cecil Seethal. IDENTITY OF PLACE, PLACES OF IDENTITIES, CHANGE OF PLACE NAMES IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA. the South African Geographical Journal, 2007, 89 (1), pp.55-63. hal-00201762 HAL Id: hal-00201762 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00201762 Submitted on 10 Jan 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. IDENTITY OF PLACE, PLACES OF IDENTITIES CHANGE OF PLACE NAMES IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA Sylvain GUYOT Cecil SEETHAL Sylvain GUYOT University of Fort-Hare, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies & University of Grenoble 2, Department of Social Geography 4, rue Etienne Marcel 38000 GRENOBLE FRANCE [email protected] Cecil SEETHAL University of Fort-Hare, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies Private Bag X1314 ALICE 5700 SOUTH AFRICA [email protected] version 3 – 30/09/2006 - 7443 words – accepted for publication, South African Geographical Journal 1-2007 The paper has not been submitted elsewhere for publication. S. GUYOT Paper realised through the CORUS research programme (IRD, University of Grenoble 1 & 2 and University of Fort-Hare). -

Drawing the Line: Cartoonists Under Threat on January 7, Two Gunmen

Drawing the line: Cartoonists under threat On January 7, two gunmen burst into the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, killing eight journalists and bringing into focus the risks cartoonists face. But with the ability of their work to transcend borders and languages, and to simplify complex political situations, the threats faced by cartoonists around the world—who are being imprisoned, forced into hiding, threatened with legal action or killed—far exceed Islamic extremism. A Committee to Protect Journalists special report by Shawn W. Crispin Published May 19, 2015 BANGKOK When Malaysia’s government initiated criminal sodomy charges against the country’s top opposition politician, the cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Ulhaque, known as Zunar, put his drawing pens to work to satirize what he viewed as a thinly veiled political power play. First published on Malaysiakini, an independent news website, and others published exclusively in a 2014 book, Zunar’s cartoons portrayed the high-profile trial as a government plot led by Prime Minister Najib Razak and his United Malays National Organization party to imprison their main political rival, Anwar Ibrahim. In one critical portrait, Zunar rendered Najib as the presiding judge in the case, with a law book conspicuously placed in a trash bin; in another, the premier was depicted pulling strings above judges drawn as shadow puppets; a third depicted Najib riding a hulking judge who is pointing a gavel at a wide-eyed Anwar. The cartoons raised not-so-subtle questions about judicial independence, a taboo topic for Malaysia’s mainstream media. “Local newspapers and TV are all controlled by the government. -

A Critique of the Rape of Justicia, with Emphasis on Seven Cartoons by Zapiro (2008 – 2010)

A critique of the Rape of Justicia, with emphasis on seven cartoons by Zapiro (2008 – 2010) by Francois Philippus Verster Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MPhil Journalism at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Prof. Lizette Rabe Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Journalism December 2010 1 Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it to any other university for a degree. Signature: Date: Copyright©2010 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 3 Abstract Regarding the work of Zapiro, a number of articles have been written, but only two post- graduate studies have been completed since 1991. On the Rape of Justicia cartoons, which were conceived recently (2008 - 2010) no academic study has been conducted. In this study seven cartoons by Zapiro are analysed, as indicated by the title and in the text. The theoretical approach for this thesis is founded on the Libertarian and Critical research models, as well as the views of the Cultural history school. As a rese arch methodology the qualitative approach was utilised. As data gathering techniques content analysis was complemented by literary and technical criteria. Interviews of selected informants were used as supplementary instruments. The goal of the study was to determine whether the Rape of Justicia cartoons can be construed as fair criticism, as is normally expected of a political commentator, while taking into account that editorial cartoonists t raditionally occupy a unique position in the field of journalism. -

8.Alence Pp.78-92

SOUTH AFRICA AFTER APARTHEID: THE FIRST DECADE Rod Alence Rod Alence is senior lecturer in international relations at the Univer- sity of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. A former Fulbright scholar in Ghana, he won the American Political Science Association’s 2002 award for best doctoral dissertation in political economy. He spent South Africa’s first decade of democracy based at universities and re- search institutions in that country. After another resounding African National Congress (ANC) victory at the polls, Thabo Mbeki began his second term as president on 27 April 2004—ten years to the day after the historic elections that brought non- racial democracy to South Africa. The indelible images of the 1994 general elections depict the snaking queues of patient voters on election day and the crowds cheering at the inauguration of Nelson Mandela as the country’s first popularly chosen president. But just weeks earlier such a storybook ending had looked improbable, as groups opposed to the new constitutional order appeared bent on violently disrupting South Africa’s founding elections. The government of the former black “home- land” of Bophuthatswana, for example, was blocking election preparations and reconsidered only when national troops arrived to crush its resis- tance. An even more ominous situation loomed in the KwaZulu homeland, where a week and a half before election day the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) government vowed noncooperation. With arms caches rumored to be spread throughout the region’s hilly countryside, many feared a bloody military confrontation. Meanwhile, white right-wing extremists backed the intransigence of the homelands, and on the eve of the elections set off a bomb in Johannesburg’s international airport. -

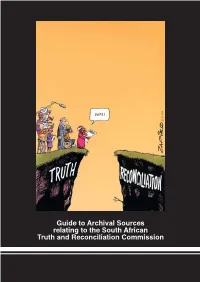

Guide to Archival Sources Relating to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Guide to Archival Sources relating to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Guide to Archival Sources relating to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Historical Papers and SAHA would like to thank the Foundation for Human Rights, who generously sponsored the layout and printing of this guide. Historical Papers The South African History Archive t +27 (11) 717 1940 t +27 (11) 717 1941 f +27 (11) 717 1927 f +27 (11) 717 1964 e [email protected] e [email protected] w www.wits.ac.za/histp w www.saha.org.za William Cullen Library William Cullen Library University of the Witwatersrand University of Witwatersrand Private Bag X1, P. O. Box 31719 PO Wits 2050, South Africa Braamfontein, 2017 CONTENTS PREFACE V ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V INTRODUCTION 1 ORIGINS AND ORGANISATION OF THE DIRECTORY 1 SOUTH AFRICAN HISTORY ARCHIVE 3 OVERVIEW OF TRC RELATED HOLDINGS 3 YASMIN SOOKA COLLECTION 3 THE WENDY WATSON COLLECTION 3 THE SALLY SEALEY COLLECTION 3 THE VERNE HARRIS COLLECTION 3 THE JANE ARGALL COLLECTION 4 THE JANET CHERRY COLLECTION 4 THE LAURA POLLECUTT COLLECTION 4 THE CHARLES VILLA-VICENCIO COLLECTION 5 THE STATE VS. P.W. BOTHA AND APPEAL 5 AUDITOR-GENERAL, REPORTS ON THE ACCOUNTS OF THE TRC 5 OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR, SYNOPSIS OF CASES INVOLVING THE TRC 5 SOUTH AFRICAN DEFENCE FORCE CONTACT BUREAU, TRC SUBMISSION 5 CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF VIOLENCE AND RECONCILIATION, TRC MATERIALS 6 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL, TRC MATERIALS 6 IDASA SOUND RECORDINGS RELATING TO THE TRC 6 NGO WORKING COMMITTEE ON REPARATIONS -

Thesis’ Primary Case Study

Chapter 1 – Introduction Rewind to 7 September 2008: it was a day which infuriated, shocked and made many South Africans question if legendary political cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro (Zapiro) had finally taken opinion too far, and opened the door for indecent editorial cartooning. The Sunday Times, South Africa’s most popular weekly newspaper, chose to print his Rape of Lady Justice cartoon (Figure 1) in which soon- to-be South African president, Jacob Zuma, is seen unbuttoning his pants, while the symbolic figure of Lady Justice is held down by four of his cadres: then-African National Congress (ANC) youth league president Julius Malema1, ANC secretary- general Gwede Mantashe, South African Communist Party (SACP) leader Blade Nzimande and then-Congress of South African Trade Unions’ (COSATU) secretary- general Zwelinzima Vavi2. The figure of Mantashe urges Zuma on with, “Go for it, boss!” – implying the imminent rape of Lady Justice. Figure 1 South Africans were divided. Many felt that the cartoonist’s gritty portrayal of Zuma hit far below the belt. Some argued that it was a disgraceful depiction in a society struggling with gender violence and high rape statistics (Mason, 2010a). 1 Expelled from the ANCYL in 2012. Now leads South Africa’s newest political party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). 2 Dismissed from this post in 2015 for allegedly breaching COSATU’s code of conduct. 8 Zapiro had not only belittled Zuma, but had, some activists felt, belittled the survivors of gender violence through the simplification of their trauma into a pervasive metaphor (Solomon, 2011). Loyal Zuma supporters, who were already critical of Zapiro’s depiction of Zuma’s showerhead3, were even more outraged by Zapiro’s damning portrayal of Zuma as a rapist; a label they believed had been dismissed legitimately by the South African legal system (Harvey, 2008).