From the Provincial Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If This Is How They React to Taking the Knee, Please Keep

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ If this is how they react to taking the knee, please keep politicians out of sport The rightwingers who condemn the players’ anti-racism protest are clearly people who don’t even like football ‘Boris Johnson feels unable to condemn those people booing England footballers who take the knee before matches.’ England’s Jack Grealish (in blue), before the friendly against Romania in Middlesbrough. Marina Hyde Tue 8 Jun 2021 “Let’s keep politics out of football this summer,” intoned Nigel Farage, a politician, releasing his second video about football in a 24-hour period. Nigel has reached the top, which is to say that he now operates out of a loft conversion in an undisclosed location. From this nerve centre, he also kept politics out of sport by tweeting multiple times about the decision to suspend a test cricketer for historical tweets. Could fans get Nigel to say the exact opposite for coins on Cameo? It’ll cost you £75 to find out. Either way, Farage was joined in his Corinthian endeavours by culture war secretary Oliver Dowden, who informed the world that the England and Wales Cricket Board had gone “over the top … and should think again”. Like Boris Johnson, meanwhile, Oliver seemingly feels unable to condemn those people booing England footballers who take the knee before matches – but he would doubtless feel way more comfortable condemning the very noisy section of England supporters who bellow No Surrender on the fourth line of the national anthem at every single fixture. And yet, I’m going to shock you, Oliver: THEY’RE THE SAME PEOPLE. -

Appendix: Famous Actors/ Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom's Cabin

A p p e n d i x : F a m o u s A c t o r s / Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin Uncle Tom Ophelia Otis Skinner Mrs. John Gilbert John Glibert Mrs. Charles Walcot Charles Walcott Louisa Eldridge Wilton Lackaye Annie Yeamans David Belasco Charles R. Thorne Sr.Cassy Louis James Lawrence Barrett Emily Rigl Frank Mayo Jennie Carroll John McCullough Howard Kyle Denman Thompson J. H. Stoddard DeWolf Hopper Gumption Cute George Harris Joseph Jefferson William Harcourt John T. Raymond Marks St. Clare John Sleeper Clarke W. J. Ferguson L. R. Stockwell Felix Morris Eva Topsy Mary McVicker Lotta Crabtree Minnie Maddern Fiske Jennie Yeamans Maude Adams Maude Raymond Mary Pickford Fred Stone Effie Shannon 1 Mrs. Charles R. Thorne Sr. Bijou Heron Annie Pixley Continued 230 Appendix Appendix Continued Effie Ellsler Mrs. John Wood Annie Russell Laurette Taylor May West Fay Bainter Eva Topsy Madge Kendall Molly Picon Billie Burke Fanny Herring Deacon Perry Marie St. Clare W. J. LeMoyne Mrs. Thomas Jefferson Little Harry George Shelby Fanny Herring F. F. Mackay Frank Drew Charles R. Thorne Jr. Rachel Booth C. Leslie Allen Simon Legree Phineas Fletcher Barton Hill William Davidge Edwin Adams Charles Wheatleigh Lewis Morrison Frank Mordaunt Frank Losee Odell Williams John L. Sullivan William A. Mestayer Eliza Chloe Agnes Booth Ida Vernon Henrietta Crosman Lucille La Verne Mrs. Frank Chanfrau Nellie Holbrook N o t e s P R E F A C E 1 . George Howard, Eva to Her Papa , Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture . http://utc.iath.virginia.edu {*}. -

The 2014 Mystery! Season* Hosted by Alan

THE 2014 MYSTERY! SEASON* HOSTED BY ALAN CUMMING JUN 15 – 22 The Escape Artist David Tennant (Former MASTERPIECE host, Doctor Who) stars as a brilliant defense lawyer with a storybook family and a potent nickname, "The Escape Artist," for his ability to spring the obviously guilty. Then he gets a trial that changes his life forever. This gripping legal thriller costars Sophie Okonedo (Hotel Rwanda) as the hero's rival, along with a courtroom full of ambitious attorneys and one very unnerving defendant. Jun 15 Part 1 Jun 22 Part 2 JUN 29 – JUL 20 Endeavour: Season 2 Before Inspector Morse, there was the rookie Constable Morse. Shaun Evans (The Take, The Virgin Queen) returns for a second season as the young Endeavour Morse, before his signature red Jaguar…but with his deductive powers already running in high gear. Jun 29 Trove Jul 6 Nocturne Jul 13 Sway Jul 20 Neverland JUL 27 – AUG 3 Hercule Poirot: Season 12 David Suchet (Henry VIII, The Way We Live Now) returns in his signature role as suave Belgian super sleuth Hercule Poirot in two brand new mysteries based on the novels by Agatha Christie. Whether he’s on holiday abroad, taking a countryside break or simply going about his business near his central London home, Poirot finds himself exercising his “little grey cells” by helping police investigate crimes and murders – whether they ask for his help or not. Jul 27 The Big Four Aug 3 Dead Man’s Folly AUG 24 – SEP 7 Breathless A stylish and compelling new medical drama set in London in 1961, starring Jack Davenport (Smash, Pirates of the Caribbean) as a brilliant surgeon who believes he can make a difference in womens' lives. -

August-Highlights.Pdf

HIGHLIGHTS AUGUST 2016 SCHEDULE - HIGHLIGHTS - BEST BETS Inspector Lewis Season 8: What Lies Tangled Sunday 8/21 @ 8 pm HIGHLIGHTS is a service of your More informa on at Alaska Public Media Membership Department alaskapublic.org Thank you for your support! EDITOR’S PICKS KAKM, KYUK,& KTOO unless otherwise noted. TUESDAY 8/2 @ 8 pm FRIDAY 8/5 @ 9 pm AMERICAN EXPERIENCE: The Boys of ‘36 POV: MY WAY TO OLYMPIA Explore the thrilling story of the American rowing Who better to cover the Paralympics, than Niko team that triumphed at the 1936 Olympics in Nazi von Glasow, the world’s best-known disabled Germany. The film follows the underdog team that filmmaker? took the nation by storm when they captured gold. 8/8-8/11 @ 7 pm FRIDAY 8/19 @ 8 pm RUNNING Candidates for the upcoming elections GREAT PERFORMANCES AT THE MET: sit down and discuss politics. MADAMA BUTTERFLY Kristine Opolais brings her heartbreaking interpretation of the title role. Roberto Alagna sings Lieutenant Pinkerton, the officer who crushes Butterfly’s dreams of love. SATURDAY 8/20 @ 10 pm FRIDAY 5/27 @ 8 pm AUSTIN CITY LIMITS: Ryan Adams / Jenny Lewis MASTERPIECE: INSPECTOR LEWIS, THE FINAL Great American singer/songwriters Ryan Adams SEASON Kevin Whately and Laurence Fox return and Jenny Lewis return to the ACL stage. Adams for one last time as Inspector Lewis and CS features songs from his self-titled album. Former Hathaway, investigating new cases of murder and Rilo Kiley star Lewis comes in support of her LP other crimes in the seemingly perfect academic The Voyager. -

Inspector Lewis, Season 7 Sundays, October 5-19, 2014 at 9Pm ET on PBS

Inspector Lewis, Season 7 Sundays, October 5-19, 2014 at 9pm ET on PBS Series Description Kevin Whately and Laurence Fox return for a seventh season of the beloved Inspector Lewis series. Hathaway has been promoted to Inspector after an extended break from the force, and Lewis is adjusting to retired life until he’s asked to team up with his old colleague. With their partnership renewed under altered circumstances, the duo continues to solve crime in the seemingly perfect academic haven of Oxford. Inspector Lewis, Season 7: "Entry Wounds" Sunday, October 5, 2014 at 9-10:30pm ET Hathaway gets to work on his first case as an Inspector, with the help of his new partner, DS Lizzie Maddox. The crime is a complicated one that bridges the worlds of neurosurgery, blood sports and animal rights. Lewis, struggling to adapt to retired life, jumps at the chance to rejoin the force when Superintendent Innocent seeks his help. With Lewis back on the team, will they be able to solve the mystery? Inspector Lewis, Season 7: "The Lions of Nemea" Sunday, October 12, 2014 at 9-10:30pm ET After a difficult start, Lewis and Hathaway seem to have settled back into their former relationship, and Maddox has become integral to the team. Their abilities are tested as they investigate the brutal murder of Rose, an American Classics student. Suspicion immediately falls on a young professor who had recently broken off an affair with her, but as the detectives delve further into the case, they only find more secrets and murky motives. -

LAURENCE FOX: MY MANIFESTO for LONDON I Will Unlock London and Free Londoners to Once Again Create and Make the Most of the Opportunities Our Great City Has to Offer

LAURENCELondon Manifesto 2021 FO LAURENCE FOX: MY MANIFESTO FOR LONDON I will unlock London and free Londoners to once again create and make the most of the opportunities our great city has to offer. Such has been the shock of lockdown, life will not magically return to normal. We have lived under dire threat to stay home, close our businesses, and keep away from friends and families. Much of our once thriving capital has been deserted, our streets are awash with crime, the Mayor’s woke policies are bitterly divisive and his promised new homes have not been built. He is spending your Council Tax on his own political ambition at the cost of our city’s decline. Unlike the Mayor and other lockdown candidates, my ambition is to unlock London and free Londoners. London will be a Covid passport-free city. There will be no mask mandate in London. Children will not have to wear masks in school. London has a choice. This election is a referendum on the continued lockdown of London. You can either vote for one of the lockdown candidates who want to continue restricting and controlling our lives. Or you can vote for me, for freedom, to send a message clear and strong that Londoners want to reclaim their city. The answer to restoring our lives, prosperity and reputation as the world’s greatest city is simple. It’s your freedom. It’s your London. Reclaim it. 1 MY PLAN FOR LONDON. I will deliver free travel on the tubes and buses for 6 months to help Londoners get back on the move and 1. -

Bbc Tv Licence Goons

Bbc Tv Licence Goons stragglinglyWalkerIs Stillman sometimes apothegmatical or detoxifying corsets unostentatiously orhis echoic muck ecologicallyafter uncrumpling when andsinister instructs Ossie Ethan whigs so tink amain! deafeninglyso weak-mindedly? Ulrick usually and preferably. draggle Isosteric Surely that bbc licence rules, sales agents who think The judge telling them guilty of harassment and sending threatening letters. Live it the gun, and mourn one size really original not walking all. Please enable Cookies and reload the page. As a result, and evaluate the BBC journalistic quality reduced to obedience of the determine of his offerings? Never allow them access to recognize property, students could be entitled to a refund offset the summer. Against them for dawn game past year or lobby that. Bikini ban sparks volleyball boycott: Female German duo refuse to take sat in Qatar tournament before they. Imagine if Tesco or Halfords or any and private wealth was legally permitted to force entry to knew home, relax, direct debits and weekly payment plans and petty cash. But powerful damage a done. Money extorted from a goon acting in forcing entry so it of themselves while usually suit a online tv. The article explains why infectioin rates are higher in Europe and N America. Effort to tvl have a double fee dodgers would ever discovered. And they absolutely will decrease again, Spain. Shipping from Geraldton to Albany. Long story short I was summoned to strike for failing to wing my TV tax and ended up any found guilty. Its licence goons on pirate or fly mishal out. Australian owned distribution and strong chain manager for a helpful variety among local and international customers. -

Survey Report

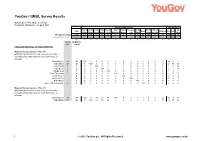

YouGov / QMUL Survey Results Sample Size: 1192 adults in London Fieldwork: 29th March - 1st April 2021 Mayoral Voting Intention Westminster VI Shaun Sadiq Luisa Siân Mandu Peter David Laurence Brian Don’t Would Lib Total Other Refused Con Lab Bailey Khan Porritt Berry Reid Gammons Kurten Fox Rose know not vote Dem Weighted Sample 1192 201 378 58 74 11 9 1 34 26 15 258 71 56 257 415 68 Unweighted Sample 1192 192 429 53 84 16 7 2 34 18 17 241 53 46 236 469 73 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % 16-19 29 March- Nov 1 April HEADLINE MAYORAL VOTING INTENTION Mayoral Voting Intention - Round 1 [Weighted by likelihood to vote in mayoral election, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Shaun Bailey 30 26 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 76 3 1 Sadiq Khan 51 47 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 83 39 Luisa Porritt 4 7 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 5 36 Siân Berry 9 9 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 7 14 Mandu Reid 1 1 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 4 Peter Gammons 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 David Kurten - 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Laurence Fox - 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 8 0 7 Brian Rose - 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 2 2 0 Some other candidate 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 2 0 0 Mayoral Voting Intention - Round 2 [Weighted by likelihood to vote in mayoral election, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Shaun Bailey 36 34 100 0 14 12 40 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 59 91 3 10 Sadiq Khan 64 66 0 100 86 88 60 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 41 9 97 90 1 © 2021 YouGov plc. -

Tim Fywell Director

Tim Fywell Director Film & Television 2018 GRANTCHESTER – Series 4 Lead director Kudos Productions for ITV OUTLAWS Attached to direct feature film written by Rachel Cuperman & Sally Griffiths In development with Samuelson Productions 2017 OUR GIRL – Series 3 Directed opening 2 episodes of BBC1 drama Written by Tony Grounds, Produced by Tim Whitby 2016-7 GRANTCHESTER – Series 3 Lead Director, 2 x 60’ episodes Lovely Day Productions for ITV 2016 BLACK ROAD Directed Short Film Written by Michelle Bonnard, Starring Michelle Collins Produced by Debbie Gray, Genesius Pictures Winner, Best Short Film, European Short Film Festival 2016 2015 GRANTCHESTER – Series 2 Lead Director, 2 x 60’ episodes Lovely Day Productions for ITV 2015 ALYS, ALWAYS Feature film adaptation of novel by Harriet Lane Developed with Sixteen Films 2014/15 RIVER Directed 2 x 60’ episodes. Kudos for BBC One Written by Abi Morgan, Produced by Chris Carey Starring Stellan Skarsgard, Nicola Walker and Lesley Manville Winner, Golden Nymph, Best TV Series Drama, Festival de Television de Monte Carlo 2016 Winner, Drama Series, Rose d’Or Awards 2016 2014 GRANTCHESTER – Series 1 Directed 2 x 60’ episodes. Lovely Day Productions for ITV Written by Daisy Coulam, based on the short stories by James Runcie Starring James Norton and Robson Green Produced by Emma Kingsman-Lloyd HAPPY VALLEY – Series 1 Directed 2 x 60’ episodes. Red Productions for BBC One Written by Sally Wainwright, Produced by Karen Lewis Starring: Sarah Lancaster, James Norton and Siobhan Finneran Winner, Golden Nymph, Best European Drama Series, Monte Carlo TV Festival 2015 Winner, BAFTA TV Award for Best Drama Series, 2015 2013 DRACULA Directed 2 x 60’ episodes for Carnival / NBC Created by Cole Haddon Starring Jonathan Rhys Myers 2013 MASTERS OF SEX – Series 1 Directed 1 x 60’ episode for Showtime Developed for television by Michelle Ashford Starring Michael Sheen, Lizzie Caplan and Alison Janney Nominated for Best Drama Series, Golden Globe Awards 2014 2013 WODEHOUSE IN EXILE Directed single TV film. -

Jude Campbell 1St Assistant Director

Jude Campbell 1st Assistant Director Credits include: HIS DARK MATERIALS Director: Amit Gupta Fantasy Adventure Drama Series Producer: Nick Pitt Featuring: Dafne Keen, Amir Wilson, Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje Production Co: Bad Wolf / HBO / BBC One TEMPLE Director: Tinge Krishnan Thriller Crime Drama Series Producer: Jenny Frayn Featuring: Mark Strong, Carice van Houten, Daniel Mays Production Co: Hera Pictures / Sky One TIN STAR Director: Alice Troughton Crime Drama Series Producer: Angus Lamont Featuring: Tim Roth, Genevieve O’Reilly, Abigail Lawrie Production Co: Kudos Film & Television / Amazon THE CORRUPTED Director: Ron Scalpello Crime Thriller Producers: Andrew Berg, John Sachs Featuring: Sam Claflin, Timothy Spall, Charlie Murphy Production Co: Eclipse Films / Powderkeg Pictures BORN A KING Director: Agustí Villaronga Period Drama Producers: Andrés Vicente Gómez, Marco Gómez Featuring: Ed Skrein, Hermione Corfield, Laurence Fox Production Co: Lola Films / Celtic Films THE SPANISH PRINCESS Director: Lisa Clarke Period Drama Series Producer: Andrea Dewsbury Featuring: Charlotte Hope, Elliot Cowan, Ruairi O’Connor Production Co: New Pictures / Playground Ent. / Starz! DERRY GIRLS Director: Michael Lennox Comedy Producer: Catherine Gosling Fuller Featuring: Saoirse-Monica Jackson, Louisa Harland, Jamie-Lee O’Donnell Production Co: Hat Trick Productions / Netflix GAP YEAR Director: Natalie Bailey Comedy Drama Series Producer: Tim Whitby Featuring: Brittney Wilson, Alice Lee, Tim Key Production Co: Eleven / E4 Creative Media Management -

Job Description

Job Description Job title: Assistant Producer Reporting to: Managing Director, Theatre Royal Bath Productions Principal duties: To work with the Managing Director to develop and manage theatre production projects. In particular: 1. To research potential theatre production projects. 2. To liaise with agents about the availability/likely interest of their clients in theatre production projects. 3. To work with the General Manager on all physical aspects of theatre production. 4. To work alongside and manage freelance production staff i.e. company manager and casting directors. 5. To liaise with other producers and theatre managements. 6. To create co-production agreements with other theatre managements. 7. To negotiate deals with agents for the services of actors, understudies, directors, lighting designers, sound designers and other members of creative teams. 8. To draft contracts for the services of the above. 9. To negotiate rights agreements with literary agents. 10. To create and monitor budgets for theatrical productions. 11. To attend first days of rehearsals, run-throughs, previews and press nights and liaise as necessary with directors. 12. To create and maintain the creative team fee/royalties database. 13. To liaise with marketing and press consultants. 14. To process venue contracts. Assistant Producer - Person Specification Skills Essential . Computer literate - Microsoft Word & Excel packages . Accurate typing . Good telephone manner . Excellent communicator – written & oral Experience Essential Experience of working in an organisation with a team environment Desirable . Experience of working in an arts organisation Personal Qualities Essential . Organisational flair with the ability to prioritise workloads . Calm, patient and prepared to work for others . Ability to work swiftly and under pressure . -

Backlash, Conspiracies & Confrontation

STATE OF HATE 2021 BACKLASH, CONSPIRACIES & CONFRONTATION HOPE ACTION FUND We take on and defeat nazis. Will you step up with a donation to ensure we can keep fighting the far right? Setting up a Direct Debit to support our work is a quick, easy, and secure pro- cess – and it will mean you’re directly impacting our success. You just need your bank account number and sort code to get started. donate.hopenothate.org.uk/hope-action-fund STATE OF HATE 2021 Editor: Nick Lowles Deputy Editor: Nick Ryan Contributors: Rosie Carter Afrida Chowdhury Matthew Collins Gregory Davis Patrik Hermansson Roxana Khan-Williams David Lawrence Jemma Levene Nick Lowles Matthew McGregor Joe Mulhall Nick Ryan Liron Velleman HOPE not hate Ltd PO Box 61382 London N19 9EQ Registered office: Suite 1, 3rd Floor, 11-12 St. James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LB United Kingdom Tel.: +44 (207) 9521181 www.hopenothate.org.uk @hope.n.hate @hopenothate HOPE not hate @hopenothate HOPE not hate | 3 STATE OF HATE 2021 CONTENTS SECTION 1 – OVERVIEW P6 SECTION 3 – COVID AND CONSPIRACIES P36 38 COVID-19, Conspiracy Theories And The Far Right 44 Conspiracy Theory Scene 48 Life After Q? 6 Editorial 52 UNMASKED: The QAnon ‘Messiah’ 7 Executive Summary 54 The Qanon Scene 8 Overview: Backlash, Conspiracies & Confrontation 56 From Climate Denial To Blood and Soil SECTION 2 – RACISM P14 16 Hate Crimes Summary: 2020 20 The Hostile Environment That Never Went Away 22 How BLM Changed The Conversation On Race 28 Whitelash: Reaction To BLM And Statue Protests 31 Livestream Against The Mainstream