Exhibition Road, London Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If This Is How They React to Taking the Knee, Please Keep

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ If this is how they react to taking the knee, please keep politicians out of sport The rightwingers who condemn the players’ anti-racism protest are clearly people who don’t even like football ‘Boris Johnson feels unable to condemn those people booing England footballers who take the knee before matches.’ England’s Jack Grealish (in blue), before the friendly against Romania in Middlesbrough. Marina Hyde Tue 8 Jun 2021 “Let’s keep politics out of football this summer,” intoned Nigel Farage, a politician, releasing his second video about football in a 24-hour period. Nigel has reached the top, which is to say that he now operates out of a loft conversion in an undisclosed location. From this nerve centre, he also kept politics out of sport by tweeting multiple times about the decision to suspend a test cricketer for historical tweets. Could fans get Nigel to say the exact opposite for coins on Cameo? It’ll cost you £75 to find out. Either way, Farage was joined in his Corinthian endeavours by culture war secretary Oliver Dowden, who informed the world that the England and Wales Cricket Board had gone “over the top … and should think again”. Like Boris Johnson, meanwhile, Oliver seemingly feels unable to condemn those people booing England footballers who take the knee before matches – but he would doubtless feel way more comfortable condemning the very noisy section of England supporters who bellow No Surrender on the fourth line of the national anthem at every single fixture. And yet, I’m going to shock you, Oliver: THEY’RE THE SAME PEOPLE. -

Generate PDF of This Page

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/1042,Exhibition-entitled-Europa-w-Rodzinie-to-open-at-Ognisko-in-London-o n-Sunday-4th.html 2021-09-30, 18:47 19.02.2018 Exhibition entitled “Europa w Rodzinie” to open at Ognisko in London on Sunday 4th March 2018. EXHIBITION Europa w Rodzinie The exhibition will open on Sunday 4th March 2018 at 12.00 noon and will run until 19th March. Ognisko Polskie - The Polish Hearth Club 55 Exhibition Road London SW7 2PN Member Price: Free Non-member Price: Free To celebrate the Centenary of Polish Independence, Ognisko Polskie and the Polish Landowners Association are proud to jointly host an Exhibition entitled “Europa w Rodzinie” to open at Ognisko on Sunday 4th March 2018. The Exhibition pays tribute to a significant sector of Polish Society, the ‘Landed Gentry’ which for centuries constituted the backbone of Poland’s cultural economic and political life. Ognisko Polskie is the natural venue for the exhibition considering its background and patronage. The author of the exhibition is the Polish Institute of National Remembrance, “Instytut Pamieci Narodowej” who kindly agreed to bring it over to London. It was first displayed in the Royal Castle in Warsaw and has subsequently been shown in most of the major cities in Poland. The exhibition traces the achievements and ethos of this social group and its virtual demise in the 20th Century during the period of communist rule. Personalities such as Witold Lutoslawski, Josef Czapski, Witold Gombrowicz, Witold Pilecki are famous figures in the 20th Century, all very different characters and all from Landed Gentry families. -

THE EXHIBITION ROAD OPENING Boris Johnson Marks the Offi Cial Unveiling Ceremony: Pages 5 and 6

“Keep the Cat Free” ISSUE 1509 FELIX 03.02.12 The student voice of Imperial College London since 1949 THE EXHIBITION ROAD OPENING Boris Johnson marks the offi cial unveiling ceremony: Pages 5 and 6 Fewer COMMENT students ACADEMIC ANGER apply to university OVERJOURNALS Imperial suffers 0.1% THOUSANDS TO REFUSE WORK RELATED TO PUBLISHER Controversial decrease from 2011 OVER PROFIT-MAKING TACTICS material on drugs Alexander Karapetian to 2012 Page 12 Alex Nowbar PAGE 3 There has been a fall in university appli- cations for 2012 entry, Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) ARTS statistics have revealed. Referred to as a “headline drop of 7.4% in applicants” by UCAS Chief Executive Mary Curnock Cook, the newly published data includes all applications that met the 15 January equal-consideration deadline. Imperial College received 14,375 applications for 2012 entry, down from 14,397 for 2011, a 0.1% decrease. Increased fees appear to have taken a toll. Towards the end of 2011 preliminary fi gures had indicated a 12.9% drop in To Bee or not to Bee university applications in comparison to the same time last year. Less marked but in Soho still signifi cant, 7.4% fewer applications were received for this cycle. Consider- Page 18 ing applications from England UCAS describes the true fi gures: “In England application rates for 18 year olds have decreased by around one percentage point in 2012 compared to a trend of in- creases of around one per cent annually HANGMAN ...Continued on Page 3 TEDx COMES TO IMPERIAL: Hangman gets a renovation PAGE 4 Page 39 2 Friday 03 february 2012 FELIX HIGHLIGHTS What’s on PICK OF THE WEEK CLASSIFIEDS This week at ICU Cinema Fashion for men. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Walker, Martyn Solid and practical education within reach of the humblest means’: the growth and development of the Yorkshire Union of Mechanics’ Institutes 1838–1891 Original Citation Walker, Martyn (2010) Solid and practical education within reach of the humblest means’: the growth and development of the Yorkshire Union of Mechanics’ Institutes 1838–1891. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/9087/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ ‘A SOLID AND PRACTICAL EDUCATION WITHIN REACH OF THE HUMBLEST MEANS’: THE GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE YORKSHIRE UNION OF MECHANICS’ INSTITUTES 1838–1891 MARTYN AUSTIN WALKER A thesis -

Exhibition Road Cultural Group (2123).Pdf

To: Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London New London Plan GLA City Hall London Plan Team Post Point 18 London SE1 2AA We welcome the opportunity to comment on the New London Plan and would be grateful if you could confirm receipt of this reponse. About us: The World’s First Planned Cultural Quarter Shared history and mission The Exhibition Road Cultural Group is a partnership of 18 leading cultural and educational organisations in and around Exhibition Road, South Kensington. Together these organisations comprise the world’s first planned cultural quarter, half of which falls within the Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Area. Created from the legacy of the Great Exhibition of 1851, and affectionately known as “Albertopolis”, this cultural quarter was established by the Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition of 1851 for the purpose of “increasing the means of industrial education and extending the influence of science and art upon productive industry”. Across its estate of 87 acres in South Kensington, the Royal Commission established three of the world’s most popular museums: The Natural History Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum and three colleges dedicated to arts, science and design: Imperial College London, the Royal College of Music and Royal College of Art and the most famous concert venue in the world, the Grade l listed Royal Albert Hall which was created originally as the Central Hall of Arts and Sciences. Over past century and a half, these institutions have been joined by other organisations that share the mission of promoting innovation and learning through the arts and science, including the Goethe Institut, Royal Geographical Society, Institute Français and the Ismaili Centre. -

Appendix: Famous Actors/ Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom's Cabin

A p p e n d i x : F a m o u s A c t o r s / Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin Uncle Tom Ophelia Otis Skinner Mrs. John Gilbert John Glibert Mrs. Charles Walcot Charles Walcott Louisa Eldridge Wilton Lackaye Annie Yeamans David Belasco Charles R. Thorne Sr.Cassy Louis James Lawrence Barrett Emily Rigl Frank Mayo Jennie Carroll John McCullough Howard Kyle Denman Thompson J. H. Stoddard DeWolf Hopper Gumption Cute George Harris Joseph Jefferson William Harcourt John T. Raymond Marks St. Clare John Sleeper Clarke W. J. Ferguson L. R. Stockwell Felix Morris Eva Topsy Mary McVicker Lotta Crabtree Minnie Maddern Fiske Jennie Yeamans Maude Adams Maude Raymond Mary Pickford Fred Stone Effie Shannon 1 Mrs. Charles R. Thorne Sr. Bijou Heron Annie Pixley Continued 230 Appendix Appendix Continued Effie Ellsler Mrs. John Wood Annie Russell Laurette Taylor May West Fay Bainter Eva Topsy Madge Kendall Molly Picon Billie Burke Fanny Herring Deacon Perry Marie St. Clare W. J. LeMoyne Mrs. Thomas Jefferson Little Harry George Shelby Fanny Herring F. F. Mackay Frank Drew Charles R. Thorne Jr. Rachel Booth C. Leslie Allen Simon Legree Phineas Fletcher Barton Hill William Davidge Edwin Adams Charles Wheatleigh Lewis Morrison Frank Mordaunt Frank Losee Odell Williams John L. Sullivan William A. Mestayer Eliza Chloe Agnes Booth Ida Vernon Henrietta Crosman Lucille La Verne Mrs. Frank Chanfrau Nellie Holbrook N o t e s P R E F A C E 1 . George Howard, Eva to Her Papa , Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture . http://utc.iath.virginia.edu {*}. -

Graphic Africa Graphic LONDON DESIGN FESTIVAL 2013: DESIGN IS EVERYWHERE

14 – 22 SEPT 2013 LONDONDESIGNFESTIVAL.COM 2013 SEPT 22 Graphic Africa 14 September — 20 October Showcasing over 20 pieces of new contemporary furniture by 16 designers from 10 countries in East, West and Southern Africa. Design Network Africa, a CKU project, looks at the current shifts and exciting developments in design happening now across the continent. See page 199 for details Platform at Habitat 208 King’s Road, SW3 5XP www.habitat.co.uk/platform LONDON DESIGN FESTIVAL 2013: DESIGN IS EVERYWHERE Over the 11 years of the London Design Festival, a vast diversity of local and international design has been showcased and celebrated. This year is no exception, with more than 300 events open to all across the capital. The Festival is a punctuation moment in the year and acts as a reminder that design is all around us, permeating every part of our lives. From the commercial to the conceptual, from the subtle to the spectacular, from the weird to the wonderful, we invite you to enjoy the great breadth of design that the London Design Festival has to offer in 2013. LDF Guide_Layout 1 7/18/13 3:31 PM Page 1 ∞≤√ INTRODUCING ANGELL, WYLLER & AARSETH BRANDS LTD, CLERKENWELL Introduction 5 INTRODUCTION Chairman Director Sir John Sorrell CBE Ben Evans Design is everywhere in London, in In a city like London, it is hard to be Great Britain and across the world. noticed. That is the whole point of the It is so much part of everyday life that Festival, a concentrated time when people take it for granted – except design is very visible. -

Ifield Road, SW10 £1,725,000 Leasehold

Ifield Road, SW10 £1,725,000 Leasehold Ifield Road, SW10 A delightful four-bedroom, period maisonette boasting neutral decor with bright and spacious rooms throughout. Further comprising kitchen, double- reception, guest wc, two en-suites and family bathroom. Ifield Road is superbly positioned on a charming residential road and ideally situated moments from trendy Fulham Road with a wide selection of restaurants, cafes and multi screened cinema, while King's Road is nearby for more extensive shopping. Transport is provided by nearby Earl’s Court, West Brompton and Fulham Broadway stations. Benefitting from close proximity to a host of top performing schools, including Bousfield primary, The London Oratory and Servite RC. Offered with no onward chain. Lease: 125 years Current Service/Maintenance Charge: To be advised - £ per annum Ground Rent: To be advised - £ per annum EPC Rating: E Current: 40 Potential: 48 £1,725,000 Leasehold 020 8348 5515 [email protected] An overview of Kensington & Chelsea The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea is a West London borough of Royal Borough status. It is an urban area, one of the most densely populated in the United Kingdom. The borough is immediately to the west of the City of Westminster and to the east of Hammersmith & Fulham. It contains major museums and universities in "Albertopolis", department stores such as Harrods, Peter Jones and Harvey Nichols and embassies in Belgravia, Knightsbridge and Kensington Gardens, and it is home to the Notting Hill Carnival, Europe's largest. It contains many of the most expensive residential districts in London and even in the world. -

In South Kensington, C. 1850-1900

JEWELS OF THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM: GENDERED AESTHETICS IN SOUTH KENSINGTON, C. 1850-1900 PANDORA KATHLEEN CRUISE SYPEREK PH.D. HISTORY OF ART UCL 2 I, PANDORA KATHLEEN CRUISE SYPEREK confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ______________________________________________ 3 ABSTRACT Several collections of brilliant objects were put on display following the opening of the British Museum (Natural History) in South Kensington in 1881. These objects resemble jewels both in their exquisite lustre and in their hybrid status between nature and culture, science and art. This thesis asks how these jewel-like hybrids – including shiny preserved beetles, iridescent taxidermised hummingbirds, translucent glass jellyfish as well as crystals and minerals themselves – functioned outside of normative gender expectations of Victorian museums and scientific culture. Such displays’ dazzling spectacles refract the linear expectations of earlier natural history taxonomies and confound the narrative of evolutionary habitat dioramas. As such, they challenge the hierarchies underlying both orders and their implications for gender, race and class. Objects on display are compared with relevant cultural phenomena including museum architecture, natural history illustration, literature, commercial display, decorative art and dress, and evaluated in light of issues such as transgressive animal sexualities, the performativity of objects, technologies of visualisation and contemporary aesthetic and evolutionary theory. Feminist theory in the history of science and new materialist philosophy by Donna Haraway, Elizabeth Grosz, Karen Barad and Rosi Braidotti inform analysis into how objects on display complicate nature/culture binaries in the museum of natural history. -

Newsletter 57

THE BHUTAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 57 PRESIDENT: SIR SIMON BOWES LYON AUTUMN 2015 Summer visit by Society members Annual Dinner A final reminder to those who have not already booked, that this Dinner will be held on Friday 27 November at The Polish Hearth Club, 55 Prince’s Gate, Exhibition Road, London SW7 2PN. Booking forms were enclosed with the last Newsletter. Please complete and return with payment to the Dinner Secretary, Mark Swinbank. Blessed, or cursed, by the hottest July temperature ever recorded in Britain, members of the Society were welcomed by Sir Simon and Lady Bowes Lyon to St Paul’s Walden Bury for a delightfully informal but informative day. The house, in the family of the Society’s President since 1725, is the place where HM the late Queen Mother grew up and was later home to her brother, David (Simon’s father). From its oldest part, the 18th century Adam style north wing, formal tree-lined allées, each leading the eye to a statue or architectural feature, radiate in the classic French goose-foot pattern. Although the show of flowering shrubs from Simon’s trips to the Himalayas were over, it was the perfect time to see a special Bhutanese tree Cornus capitata in full bloom (or, technically, bract). This provided a good backdrop for the group photograph above. After a light lunch next to a gnarled but magnificent old oak, Caroline showed guests round the house, with its original 18th century plasterwork ceilings and some very recognisable royal pieces: a portrait of the Queen Mother (one half of a pair with that of her brother David), and a rocking horse which had been ridden by the young princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, as seen in a photograph from 1932. -

The 2014 Mystery! Season* Hosted by Alan

THE 2014 MYSTERY! SEASON* HOSTED BY ALAN CUMMING JUN 15 – 22 The Escape Artist David Tennant (Former MASTERPIECE host, Doctor Who) stars as a brilliant defense lawyer with a storybook family and a potent nickname, "The Escape Artist," for his ability to spring the obviously guilty. Then he gets a trial that changes his life forever. This gripping legal thriller costars Sophie Okonedo (Hotel Rwanda) as the hero's rival, along with a courtroom full of ambitious attorneys and one very unnerving defendant. Jun 15 Part 1 Jun 22 Part 2 JUN 29 – JUL 20 Endeavour: Season 2 Before Inspector Morse, there was the rookie Constable Morse. Shaun Evans (The Take, The Virgin Queen) returns for a second season as the young Endeavour Morse, before his signature red Jaguar…but with his deductive powers already running in high gear. Jun 29 Trove Jul 6 Nocturne Jul 13 Sway Jul 20 Neverland JUL 27 – AUG 3 Hercule Poirot: Season 12 David Suchet (Henry VIII, The Way We Live Now) returns in his signature role as suave Belgian super sleuth Hercule Poirot in two brand new mysteries based on the novels by Agatha Christie. Whether he’s on holiday abroad, taking a countryside break or simply going about his business near his central London home, Poirot finds himself exercising his “little grey cells” by helping police investigate crimes and murders – whether they ask for his help or not. Jul 27 The Big Four Aug 3 Dead Man’s Folly AUG 24 – SEP 7 Breathless A stylish and compelling new medical drama set in London in 1961, starring Jack Davenport (Smash, Pirates of the Caribbean) as a brilliant surgeon who believes he can make a difference in womens' lives. -

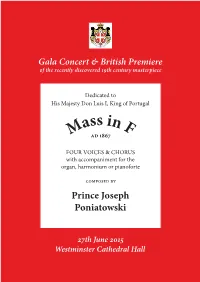

S in F M AD 1867

Gala Concert & British Premiere of the recently discovered 19th century masterpiece Dedicated to His Majesty Don Luis I, King of Portugal ass in F M AD 1867 FOUR VOICES & CHORUS with accompaniment for the organ, harmonium or pianoforte COMPOSED BY Prince Joseph Poniatowski 27th June 2015 Westminster Cathedral Hall 1 H. M. Stanisław August Poniatowski, last King of Poland Stanisław Poniatowski (1667–1762) Casimir Stanislaus August Andrew Michael (1721–1781) (1732–1798) (1735–1773) (1736–1794) Cancellor of Poland Last King of Poland General in Austrian Army Archibishop of Gniezno (1764–1795) Primate of Poland Stanislaw Jozef Antoni (1757–1833) (1763–1813) Treasurer of Lithuania Field Marshal in Napoleon’s Army Jozef Michal Ksawery Franciszek Jan Poniatowski (1816–1873) Born in Rome: Giuseppe Michele Severio Francesco Luci, Principe di Monte Rotondo, Tuscan Plenipotentiary (Brussels 1849, London 1850–53, Paris 1854), Senator French Parliament (1854–1871). Opera Tenor and Composer of 12 Operas and Mass in F In the presence of His Eminence Cardinal Vincent Nichols The Association of Polish Knights of Malta UK supported by The Polish Heritage Society UK and The Embassy of the Republic of Poland presents: Prince Joseph Poniatowski’s Mass in F under the Patronage of His Excellency Mr Witold Sobków Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of The Republic of Poland to The Court of St. James’s ARCHBISHOP’S HOUSE, WESTMINSTER, LONDON SW1P 1QJ Dear Friends, It is a privilege that tonight for the first time Prince Josef Poniatowski’s Mass in “F” is going to be performed here in Westminster Cathedral Hall in London. When I was approached by the Polish Knights of Malta UK and The Polish Heritage Society UK to be Patron of this historic event, I accepted immediately.