Članci the Making of „Black Hand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Diplomats Fail: Aostrian and Rossian Reporting from Belgrade, 1914

WHEN DIPLOMATS FAIL: AOSTRIAN AND ROSSIAN REPORTING FROM BELGRADE, 1914 Barbara Jelavich The mountain of books written on the origins of the First World War have produced no agreement on the basic causes of this European tragedy. Their division of opinion reflects the situation that existed in June and July 1914, when the principal statesmen involved judged the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg throne, and its consequences from radically different perspectives. Their basic misunderstanding of the interests and viewpoints 'of the opposing sides contributed strongly to the initiation of hostilities. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the importance of diplomatic reporting, particularly in the century before 1914 when ambassadors were men of influence and when their dispatches were read by those who made the final decisions in foreign policy. European diplomats often held strong opinions and were sometimes influenced by passions and. prejudices, but nevertheless throughout the century their activities contributed to assuring that this period would, with obvious exceptions, be an era of peace in continental affairs. In major crises the crucial decisions are always made by a very limited number of people no matter what the political system. Usually a head of state -- whether king, emperor, dictator, or president, together with those whom he chooses to consult, or a strong political leader with his advisers- -decides on the course of action. Obviously, in times of international tension these men need accurate information not only from their military staffs on the state of their and their opponent's armed forces and the strategic position of the country, but also expert reporting from their representatives abroad on the exact issues at stake and the attitudes of the other governments, including their immediate concerns and their historical background. -

NJDARM: Collection Guide

NJDARM: Collection Guide - NEW JERSEY STATE ARCHIVES COLLECTION GUIDE Record Group: Governor Franklin Murphy (1846-1920; served 1902-1905) Series: Correspondence, 1902-1905 Accession #: 1989.009, Unknown Series #: S3400001 Guide Date: 1987 (JK) Volume: 6 c.f. [12 boxes] Box 1 | Box 2 | Box 3 | Box 4 | Box 5 | Box 6 | Box 7 | Box 8 | Box 9 | Box 10 | Box 11 | Box 12 Contents Explanatory Note: All correspondence is either to or from the Governor's office unless otherwise stated. Box 1 1. Elections, 1901-1903. 2. Primary election reform, 1902-1903. 3. Requests for interviews, 1902-1904 (2 files). 4. Taxation, 1902-1904. 5. Miscellaneous bills before State Legislature and U.S. Congress, 1902 (2 files). 6. Letters of congratulation, 1902. 7. Acknowledgements to letters recommending government appointees, 1902. 8. Fish and game, 1902-1904 (3 files). 9. Tuberculosis Sanatorium Commission, 1902-1904. 10. Invitations to various functions, April - July 1904. 11. Requests for Governor's autograph and photograph, 1902-1904. 12. Princeton Battle Monument, 1902-1904. 13. Forestry, 1901-1905. 14. Estate of Imlay Clark(e), 1902. 15. Correspondence re: railroad passes & telegraph stamps, 1902-1903. 16. Delinquent Corporations, 1901-1905 (2 files). 17. Robert H. McCarter, Attorney General, 1903-1904. 18. New Jersey Reformatories, 1902-1904 (6 files). Box 2 19. Reappointment of Minister Powell to Haiti, 1901-1902. 20. Corporations and charters, 1902-1904. 21. Miscellaneous complaint letters, December 1901-1902. file:///M|/highpoint/webdocs/state/darm/darm2011/guides/guides%20for%20pdf/s3400001.html[5/16/2011 9:33:48 AM] NJDARM: Collection Guide - 22. Joshua E. -

How Did the First World War Start?

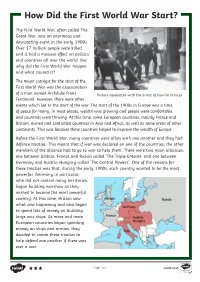

How Did the First World War Start? The First World War, often called The Great War, was an enormous and devastating event in the early 1900s. Over 17 million people were killed and it had a massive effect on politics and countries all over the world. But why did the First World War happen and what caused it? The major catalyst for the start of the First World War was the assassination of a man named Archduke Franz Picture associated with the arrest of Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand. However, there were other events which led to the start of the war. The start of the 1900s in Europe was a time of peace for many. In most places, wealth was growing and people were comfortable and countries were thriving. At this time, some European countries, mainly France and Britain, owned and controlled countries in Asia and Africa, as well as some areas of other continents. This was because these countries helped to improve the wealth of Europe. Before the First World War, many countries were allies with one another and they had defence treaties. This meant that if war was declared on one of the countries, the other members of the alliance had to go to war to help them. There were two main alliances, one between Britain, France and Russia called ‘The Triple Entente’ and one between Germany and Austria-Hungary called ‘The Central Powers’. One of the reasons for these treaties was that, during the early 1900s, each country wanted to be the most powerful. Germany in particular, who did not control many territories, began building warships as they wished to become the most powerful country. -

THE WARP of the SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-Westernism, Russophilia, Traditionalism

HELSINKI COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA studies17 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism... BELGRADE, 2016 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism… Edition: Studies No. 17 Publisher: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia www.helsinki.org.rs For the publisher: Sonja Biserko Reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Dubravka Stojanović Prof. Dr. Momir Samardžić Dr Hrvoje Klasić Layout and design: Ivan Hrašovec Printed by: Grafiprof, Belgrade Circulation: 200 ISBN 978-86-7208-203-6 This publication is a part of the project “Serbian Identity in the 21st Century” implemented with the assistance from the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. CONTENTS Publisher’s Note . 5 TRANSITION AND IDENTITIES JOVAN KOMŠIĆ Democratic Transition And Identities . 11 LATINKA PEROVIĆ Serbian-Russian Historical Analogies . 57 MILAN SUBOTIĆ, A Different Russia: From Serbia’s Perspective . 83 SRĐAN BARIŠIĆ The Role of the Serbian and Russian Orthodox Churches in Shaping Governmental Policies . 105 RUSSIA’S SOFT POWER DR. JELICA KURJAK “Soft Power” in the Service of Foreign Policy Strategy of the Russian Federation . 129 DR MILIVOJ BEŠLIN A “New” History For A New Identity . 139 SONJA BISERKO, SEŠKA STANOJLOVIĆ Russia’s Soft Power Expands . 157 SERBIA, EU, EAST DR BORIS VARGA Belgrade And Kiev Between Brussels And Moscow . 169 DIMITRIJE BOAROV More Politics Than Business . 215 PETAR POPOVIĆ Serbian-Russian Joint Military Exercise . 235 SONJA BISERKO Russia and NATO: A Test of Strength over Montenegro . -

Microfilm Publication M617, Returns from U.S

Publication Number: M-617 Publication Title: Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916 Date Published: 1968 RETURNS FROM U.S. MILITARY POSTS, 1800-1916 On the 1550 rolls of this microfilm publication, M617, are reproduced returns from U.S. military posts from the early 1800's to 1916, with a few returns extending through 1917. Most of the returns are part of Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office; the remainder is part of Record Group 393, Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920, and Record Group 395, Records of United States Army Overseas Operations and Commands, 1898-1942. The commanding officer of every post, as well ad commanders of all other bodies of troops such as department, division, brigade, regiment, or detachment, was required by Army Regulations to submit a return (a type of personnel report) to The Adjutant General at specified intervals, usually monthly, on forms provided by that office. Several additions and modifications were made in the form over the years, but basically it was designed to show the units that were stationed at a particular post and their strength, the names and duties of the officers, the number of officers present and absent, a listing of official communications received, and a record of events. In the early 19th century the form used for the post return usually was the same as the one used for regimental or organizational returns. Printed forms were issued by the Adjutant General’s Office, but more commonly used were manuscript forms patterned after the printed forms. -

Law School Announcements 1903-1904 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications Summer 6-1903 Law School Announcements 1903-1904 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 1903-1904" (1903). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 29. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ttbc 1llnh'crsttp of (tbtcago FOUNDED BY JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER ANNOU'NCEMENT,S VOL. III JUNE, 1903 NO.4 THE LAW SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO TABLE OF CONTENTS CALENDAR FOR THE YEAR 1903--4 .' 2 The Professional Curriculum: OFFICERS OF ADMINISTRATION 3 First-Year Courses. THE FACULTY. 3 Second and Third-Year Courses INTRODUCTORY: COURSES OF IN'STRUCTION, 1903-4 : Organization and Purpose 3 The Pre-legal Curriculum. H) The Library 4 Requirements for Admission 4 The Professional Curriculum: Arrangement of Courses 5 First-Year Courses 11 Degrees 5 Second and Third-Year Courses 11 OF General Information .. 6 REGISTRATION STUDENTS, 1902-3 12 THE CURRICULUM: Summary of Attendance 15 The Pre-legal Curriculum 6 THE SUMMER QUARTER, 1903 .' 16 ; �� PUBLISHED SIX TIMES A YEAR BY �k�(� , fL THE UN IV E R SIT Y 0 F CHI C AGO 4(A�:hIV� . -

Moderno BELGRADO

moderno BELGRADO Legado y alteridad de la urbanidad Europea Mila Nikolic Episodios Urbanos Significativos: Liberation of Belgrade 1789 Marshal Gideon Ernst Laudon captures Belgrade 1791 Peace treaty of Svishtov gives Belgrade back to the Turks 1806 Karađorđe liberates Belgrade town and Belgrade becomes the capital of Serbia again 1808 The Great School was established in Belgrade 1813 The Turks reconquer Belgrade 1815 Miloš Obrenović started the Second Serbian Insurrection 1830 Sultan's hatišerif (charter) on Serbian autonomy 1831 First printing-house in Belgrade was put into operation 1835 First newspaper - "Novine srbske" is published in Belgrade 1840 Opening of the first post office in Belgrade 1841 Belgrade becomes the capital of the Princedom of Serbia in the first period of rule of Mihailo Obrenović 1844 The National Museum was established in Belgrade 1855 First telegraphic line Belgrade - Aleksinac was established 1862 Conflict at Čukur-česma and bombardment of Belgrade town from the fortress under Turkish control led to international decision that the Turks must leave Belgrade 1854 ~1815 Episodios Urbanos Significativos The Capital of Serbia and Yugoslavia 1867 In Kalemegdan, the Turkish commander of Belgrade Ali-Riza pasha gives the keys of Belgrade to Knez Mihailo. The Turks finally leave Belgrade 1878 The Berlin Congress recognized the independence of Serbia 1882 Serbia becomes a kingdom, and Belgrade its capital 1883 First telephone lines are installed in Belgrade 1884 Railway station and railway bridge over Sava were constructed -

Tech Names Girls - 1914 to 1987

TECH NAMES GIRLS - 1914 TO 1987 GIRLS – A AARON, Julia Farley (Tarbox) - T-35 - Born: 2 September 1916 - Died: 27 May 2005 AARON, Letriunna -T-87 - Memphis TN ABBOTT, Ruth (Swafford) - T -62 - Born: 5 July 1944 - Died: 12 May 2016 ABERCROMBIE, Grace - T-60 - (Need to find) ABERNATHY, Ginger Ann (McEvoy) - T-60 -Memphis TN - (Need to find) ABERNATHY, Margaret Jarvin (Patterson) - T-37 - Born: 27 April 1918 - Died: 27 November 1989 ABLES, Dale (Huet) - T-55 - Born: 3 October 1937 - still living 20 Sep 2012- (Need to find) ABLES, Gayle (Lynch) - T-55 - Born: 3 October 1937 - still living 20 Sep 2012 - (Need to find) ABRAM, Valerie (King) - T-77 - (Need to find) ABSTON, Helen - T-83 – (Need to find) ACOSTA, Dorothy Naoma (Burns) - T-38 - Born: 14 March 1920 - Died: 6 April 2001 ACRED, Florence Margaret - T-37 - Born: 2 April 1919 - Died: 1 March 2004 ACRED, Virginia (Ferguson) - T-32 - Born: 2 November 1912 -Died: 22 July 2001 ACREE, Bettye Ann - T -56- (Need to find) ACREE, Edna Leona (Mosley) - T-42 - Born 13 July 1924 - Died:17 July 2005 ACREE, Geri (Maxwell) - T-62 - Born: 23 February 1944 - 3427 Earlynn Drive, Memphis TN 38133 ACREE, Mildred Ann (Schneller) - T-49 - Born: 17 December 1931 - Died: 26 November 2008 ACTON, Margaret Ida (Underdown) - T-55 - Born: 3 July 1937 - Died: 27 November 2012 ADAMS, Alice Armon (Black) - T-32 - Born: 14 September 1916 - Died: 15 December 2000 ADAMS, Anita - T-83 – (Need to find) ADAMS, Anita -T-87 - (Need to find) ADAMS, Arlene - T-63 - (Need to find) ADAMS, Betty - T-59 - (Need to find) ADAMS, Brenda Faye - T-82 - (Need to find) ADAMS, Ellanora (Wade) - T-28 - Born: 29 June 1909 - Died: 24 May 1980 ADAMS, Gloria (Ferguson) - T -44 - Born: 18 April 1926 – Died: 22 July 2020 ADAMS, Jean (Hart) - T-50 - Born: 8 December 1932 - Died: 14 April 1976 ADAMS, Labrigette - T-84 - (Need to find) ADAMS, LaVerne -T-85 - (Need to find) ADAMS, Lillian F. -

The London Gazette, June 16, 1903. 3785

THE LONDON GAZETTE, JUNE 16, 1903. 3785 The undermentioned appointments have been South Africa, is granted the honorary rank of made to the ' Staff of the Somaliland Field Lieutenant in the Army. Dated 1st June, 1902. Force:— Lieutenant B. R. Moberly, Indian Army, to be RESERVE OF OFFICERS. Staff Officer, Base and Lines of Communi- The undermentioned Captains resign their cation, Obbia. Dated 5th March, 1903. Commissions. Dated 17th June, 1903 :— To be Special Service Officers, and to be graded W. McKay. for pay Rate XIII, Scale B, Article 115, Royal H. F. Easton. Warrant of 26th October, 1900 :— Captain and Brevet Major A. W. S. Ewing, The ERRATUM. Prince of Wales's (North Staffordshire Regi- Major F. G. W. Jones was promoted for " service ment). Dated 7th May, 1903. in South Africa," and not as stated in the Captain F. D. Farquhar, D.S.O., 'Coldstream London Gazette of the 24th February, 1903. Guards. Dated 8th May, 1903. To be Special Service Officers, and to be graded for pay Rate XIV, Scale B, Article 115, Royal Warrant 26th October, 1900:— Civil Service Commission, Lieutenant R. W. M. Stevens, The Royal Irish June 16, 1903. Rifles. Dated 7th May, 1903. The Civil Service Commissioners hereby give Lieutenant C. L. Smith, The Duke of Cornwall's notice that the Open Competitive Examination Light Infantry. Dated 15th May, 1903. for the situation of Junior Clerk in the High SCHOOLS OP INSTRUCTION FOR MOUNTED Court of Justice, Ireland, of which notice was INFANTRY. given in the London Gazette of the 9th instant, To be Commandants: — will commence on the 22nd July, instead of on Major and Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel A. -

Prilozi 43 2014 Eng.Indd

%RMDQ$OHNVRYForgotten Yugoslavism and anti-clericalism of Young Bosnians Prilozi • Contributions, 43, Sarajevo, 2014, 79-87 UDK 329.78(497.15)"1906/1914" )25*277(1<8*26/$9,60$1'$17,&/(5,&$/,60 2)<281*%261,$16 %RMDQ$OHNVRY 8&/6FKRRORI6ODYRQLFDQG(DVW(XURSHDQ6WXGLHV/RQGRQ Abstract: Worldviews and political ambitions of Young Bosnians were a far cry from later and contemporary emanations of Serbian nationalism, as evident in the- ir Yugoslavism and staunch anti-clericalism. They should neither be praised for what they did nor blamed for what happened later. Their act can be understood and interpreted only in its own historical context, which opens new avenues for resear- ch away from false analogies and political abuses. 7KHUHLVDQROGQREOHFXVWRPSUDFWLVHGLQWKH8QLWHG.LQJGRPZKHUHE\DFDGHP- LFV DQGRWKHUV GHFODUHDQLQWHUHVWZKHQGLVFXVVLQJPDWWHUVSHUVRQVWRZKLFKWKH\ might have a relation. Unfortunately this has not been the case in the historiography RIWKRVHKLJKO\GLVSXWHGLVVXHVVXFKDVWKHRULJLQVRI)LUVW:RUOG:DU1 Despite the IDFWWKDWGRFXPHQWDU\HYLGHQFHIURPDOOVLGHVZDVSXEOLVKHGDOUHDG\LQWKHLQWHUZDU SHULRGWKHGLIIHUHQFHVRILQWHUSUHWDWLRQDQGRSLQLRQDELGHRUHYHQLQFUHDVHZLWKWLPH VRWKDWZKDWLVEHLQJZULWWHQRIWHQUHIOHFWVWKHFRQWH[WDQGEDFNJURXQGRILWVDXWKRU UDWKHUWKDQWKHHYHQWDQDO\VHG,ZDQWWREUHDNWKLVFLUFOHRIXQDFNQRZOHGJHGELDV E\GHFODULQJWKDW,ZDVERUQDQGUDLVHGLQWKHVWUHHWEHDULQJWKHQDPHRI1HGHOMNR ýDEULQRYLüWKHIDLOHG6DUDMHYRERPEHUDQGWKXVIURPHDUO\DJHVXEMHFWWRWKHJUDQG 6RFLDOLVW<XJRVODYLD¶VQDUUDWLYHRI<RXQJ%RVQLDQVDVIUHHGRPILJKWHUVDQG<XJR- 1)RUWKHPDQLSXODWLRQRIDUFKLYDOUHFRUGVDQGHYLGHQFHUHODWLQJWKHWKHUHVSRQVLELOLW\IRUWKH -

The Assassination of Franz Ferdinand, As It Happened - Telegraph

4/21/2015 First World War centenary: the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, as it happened - Telegraph First World War centenary: the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, as it happened On Sunday June 28 1914 in Sarajevo, Gavrilo Princip fired the shot that killed the Archduke and started the train of events that led to global war. Here is a step by step account of how the dramatic day unfolded The Daily Telegraph, June 29 1914 By Richard Preston 8:19PM BST 27 Jun 2014 Our journey starts with an extremely promising omen. Here our car burns, and down there they will throw bombs at us. Archduke Franz Ferdinand comments wryly on the fact that his journey to Bosnia in June 1914 begins with his car overheating The Archduke: Franz Ferdinand, the bumptious, littleloved 51yearold nephew of the ailing Emperor Franz Joseph, was heir presumptive to the AustroHungarian throne. In 1913 he was made inspector general of the armed forces of AustriaHungary; it was this role that took him to Bosnia in June 1914, to inspect the army’s summer manoeuvres. The Duchess: Franz Ferdinand married Countess Sophie Chotek for love, for which both paid a price. She was from a Czech noble family but was deemed unfit to be a Habsburg bride; she had been a ladyinwaiting to Archduchess Isabella, whose sister Franz Ferdinand was expected to marry. Their marriage was morganatic, meaning their children were excluded from the line of http://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/world-war-one/10930863/First-World-War-centenary-the-assassination-of-Franz-Ferdinand-as-it-happened.html 1/12 4/21/2015 First World War centenary: the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, as it happened - Telegraph succession. -

LARSON-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf

THE NEW “OLD COUNTRY” THE KINGDOM OF YUGOSLAVIA AND THE CREATION OF A YUGOSLAV DIASPORA 1914-1951 BY ETHAN LARSON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Maria Todorova, Chair Professor Peter Fritzsche Professor Diane Koenker Professor Ulf Brunnbauer, University of Regensburg ABSTRACT This dissertation reviews the Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s attempt to instill “Yugoslav” national consciousness in its overseas population of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, as well as resistance to that same project, collectively referred to as a “Yugoslav diaspora.” Diaspora is treated as constructed phenomenon based on a transnational network between individuals and organizations, both emigrant and otherwise. In examining Yugoslav overseas nation-building, this dissertation is interested in the mechanics of diasporic networks—what catalyzes their formation, what are the roles of international organizations, and how are they influenced by the political context in the host country. The life of Louis Adamic, who was a central figure within this emerging network, provides a framework for this monograph, which begins with his arrival in the United States in 1914 and ends with his death in 1951. Each chapter spans roughly five to ten years. Chapter One (1914-1924) deals with the initial encounter between Yugoslav diplomats and emigrants. Chapter Two (1924-1929) covers the beginnings of Yugoslav overseas nation-building. Chapter Three (1929-1934) covers Yugoslavia’s shift into a royal dictatorship and the corresponding effect on its emigration policy.