From Runic Stone to Charter Transformation of Property Confirmation in 11Th and 12Th Century Denmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saami and Scandinavians in the Viking

Jurij K. Kusmenko Sámi and Scandinavians in the Viking Age Introduction Though we do not know exactly when Scandinavians and Sámi contact started, it is clear that in the time of the formation of the Scandinavian heathen culture and of the Scandinavian languages the Scandinavians and the Sámi were neighbors. Archeologists and historians continue to argue about the place of the original southern boarder of the Sámi on the Scandinavian peninsula and about the place of the most narrow cultural contact, but nobody doubts that the cultural contact between the Sámi and the Scandinavians before and during the Viking Age was very close. Such close contact could not but have left traces in the Sámi culture and in the Sámi languages. This influence concerned not only material culture but even folklore and religion, especially in the area of the Southern Sámi. We find here even names of gods borrowed from the Scandinavian tradition. Swedish and Norwegian missionaries mentioned such Southern Sámi gods such as Radien (cf. norw., sw. rå, rådare) , Veralden Olmai (<Veraldar goð, Frey), Ruona (Rana) (< Rán), Horagalles (< Þórkarl), Ruotta (Rota). In Lule Sámi we find no Scandinavian gods but Scandinavian names of gods such as Storjunkare (big ruler) and Lilljunkare (small ruler). In the Sámi languages we find about three thousand loan words from the Scandinavian languages and many of them were borrowed in the common Scandinavian period (550-1050), that is before and during the Viking Age (Qvigstad 1893; Sammallahti 1998, 128-129). The known Swedish Lapponist Wiklund said in 1898 »[...] Lapska innehåller nämligen en mycket stor mängd låneord från de nordiska språken, av vilka låneord de äldsta ovillkorligen måste vara lånade redan i urnordisk tid, dvs under tiden före ca 700 år efter Kristus. -

The Viking Age

Laval University From the SelectedWorks of Fathi Habashi March, 2020 The iV king Age Fathi Habashi Available at: https://works.bepress.com/fathi_habashi/615/ The Viking Age INTRODUCTION The Viking Age (793-1066) is a period in history during which the Scandinavians expanded and built settlements throughout Europe. They are sometimes referred to as Norsemen and known to the Greek as Varangians. They took two routes: the East - - the present-day Ukraine and Russia, and the West mainly in the present-day Iceland, Greenland, Newfoundland, Normandy, Italy, and the British Isles. The Viking were competent sailors, adept in land warfare as well as at sea. Their ships were light enough to be carried over land from one river system to another. Viking ships The motivation of the Viking to invade East and West is a problem to historians. Many theories were given none was the answer. For example, retaliation against forced conversion to Christianity by Charlemagne by killing any who refused to become baptized, seeking centers of wealth, kidnapping slaves, and a decline in the profitability of old trade routes. Viking ship in Oslo Museum The Vikings raids in the East and the West of Europe VIKINGS IN THE EAST The Dnieber The Vikings of Scandinavia came by way of the Gulf of Finland and sailed up the Dvina River as far as they could go, and then carried their ships across land to the Dnieper River, which flows south to the Black Sea. They raided villages then they became interested in trading with the Slavs. Using the Dnieper, they carried shiploads of furs, honey, and wax south to markets on the Black Sea, or sailed across that sea trade in Constantinople. -

Towards the Kalmar Union

S P E C I A L I Z E D A G E N C I E S TOWARDS THE KALMAR UNION Dear Delegates, Welcome to the 31st Annual North American Model United Nations 2016 at the University of Toronto! On behalf of all of the staff at NAMUN, we welcome you to the Specialized Agency branch of the conference. I, and the rest of the committee staff are thrilled to have you be a delegate in Scandinavia during the High Middle Ages, taking on this challenging yet fascinating topic on the futures of the three Scandinavian Kingdoms in a time of despair, poverty, dependence and competitiveness. This will truly be a new committee experience, as you must really delve into the history of these Kingdoms and figure out how to cooperate with each other without sending everyone into their demise. To begin, in the Towards the Kalmar Union Specialized Agency, delegates will represent influential characters from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, which include prominent knights, monarchs, nobles, and important religious figures who dominate the political, military and economic scenes of their respective Kingdoms. The impending issues that will be discussed at the meeting in Kalmar, Sweden include the future of the Danish and Norwegian crowns after the death of the sole heir to the thrones, Olaf II. Here, two distant relatives to Valdemar IV have a claim to the throne and delegates will need to decide who will succeed to the throne. The second order of business is to discuss the growing German presence in Sweden, especially in major economic cities. -

The Conversion of Scandinavia James E

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 1978 The ah mmer and the cross : the conversion of Scandinavia James E. Cumbie Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Cumbie, James E., "The ah mmer and the cross : the conversion of Scandinavia" (1978). Honors Theses. Paper 443. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES 11111 !ill iii ii! 1111! !! !I!!! I Ill I!II I II 111111 Iii !Iii ii JIJ JIJlllJI 3 3082 01028 5178 .;a:-'.les S. Ci;.r:;'bie ......:~l· "'+ori·.:::> u - '-' _.I".l92'" ..... :.cir. Rillin_: Dr. ~'rle Dr. :._;fic:crhill .~. pril lJ, 197f' - AUTHOR'S NOTE The transliteration of proper names from Old Horse into English appears to be a rather haphazard affair; th€ ~odern writer can suit his fancy 'Si th an~r number of spellings. I have spelled narr.es in ':1ha tever way struck me as appropriate, striving only for inte:::-nal consistency. I. ____ ------ -- The advent of a new religious faith is always a valuable I historical tool. Shifts in religion uncover interesting as- pects of the societies involved. This is particularly true when an indigenous, national faith is supplanted by an alien one externally introduced. Such is the case in medieval Scandinavia, when Norse paganism was ousted by Latin Christ- ianity. -

Learning from Scandinavia's Game of Thrones

Learning from Scandinavia’s By John Bechtel, Freelance Writerr either heritage nor history are boring, arcane subjects best suited for Heritage is about memories and identities; it seductively promises to aging seniors with nothing better to do than take dreamy trips down answer the question, where do I belong? Heritage is about geography and nostalgia lane. The only thing that can be said to be boring about topography and landscapes of the familiar; it is about emotional attachments to history from time to time is its teachers, who fail to communicate that history land and language and places; it is about our personal history and experiences does in fact repeat itself, its lessons lost upon successive generations who with such places and things, especially from an early age. But our attitudes and cannot remember yesteryear’s unkept political promises and failed ideologies. longings are also affected by others, outsiders, who may visit but who never lived it, who have other memories of other places. Both the insider’s viewpoint History is a living art; what we do, think, and act out today is tomorrow’s and the tourist’s perceptions can be valuable, because there is a certain amount history. How can that be boring? History is about taking nothing for granted, of mythmaking and whitewashing in all heritage stories. To truly benefit making no assumptions about the present or the future. History is an antidote from our heritage, we need to do more than romanticize the past. We need to to overconfidence by today’s ideologues. History is about insatiable curiosity experience it as closely as possible to the way it was to live it, not just by the about how we got to where we are, and the interplay of ideas, people—human elites of the day, but at all levels of society. -

The Goddess: Myths of the Great Mother Christopher R

Gettysburg College Faculty Books 2-2016 The Goddess: Myths of the Great Mother Christopher R. Fee Gettysburg College David Leeming University of Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, and the Religion Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Fee, Christopher R., and David Leeming. The Goddess: Myths of the Great Mother. London, England: Reaktion Press, 2016. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books/95 This open access book is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Goddess: Myths of the Great Mother Description The Goddess is all around us: Her face is reflected in the burgeoning new growth of every ensuing spring; her power is evident in the miracle of conception and childbirth and in the newborn’s cry as it searches for the nurturing breast; we glimpse her in the alluring beauty of youth, in the incredible power of sexual attraction, in the affection of family gatherings, and in the gentle caring of loved ones as they leave the mortal world. The Goddess is with us in the everyday miracles of life, growth, and death which always have surrounded us and always will, and this ubiquity speaks to the enduring presence and changing masks of the universal power people have always recognized in their lives. -

Viking Art, Snorri Sturluson and Some Recent Metal Detector Finds. Fornvännen 113

•• JOURNAL OF SWEDISH ANTIQUARIAN RESEARCH 2018:1 Art. Pentz 17-33_Layout 1 2018-02-16 14:37 Sida 17 Viking art, Snorri Sturluson and some recent metal detector finds By Peter Pentz Pentz, P., 2018. Viking art, Snorri Sturluson and some recent metal detector finds. Fornvännen 113. Stockholm. This paper seeks to contribute to a recent debate on the use of private metal detect- ing and its value within archaeology. Specifically it explores – by presenting some recently found Viking Period artefacts from Denmark – how private metal detect- ing can contribute to our understanding of Viking minds. By bringing together the myths as related by Snorri Sturluson in the early 13th century with the artefacts, I argue that thanks to private metal detecting through the last decades, our ability to recognise Viking art as narrative art has improved substantially. Peter Pentz, National Museum of Denmark, Ny Vestergade 10, DK–1471 København K [email protected] Over 60 years ago, Thorkild Ramskou (1953) the main problems in understanding Viking art described Viking art as almost exclusively deco- is the scarcity of reference materials. We largely rative, only functioning as a covering for plain know Norse mythology and its narratives through surfaces. In the rare cases where it was represen- Medieval Christian authors, in particular Snorri. tative, quality was poor. Viking artists, he stated, Hence, the myths have come down to us biased, preferred to portray scenes from myths of the reinterpreted and even now and then propagan- gods and heroic legends. Such scenes functioned dised. Furthermore, what survived is only a selec- as mnemonics; for the viewer they would recall tion. -

The Viking Age Study Guide Vocabulary

The Viking Age Study Guide Directions: Study the below concepts and information and you will be prepared for class and assessments. Map: Artic Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Newfoundland, Greenland, Iceland, Scandinavia, Norway, Sweden, Denmark Vocabulary Norsemen: Northmen Longship/Drekar: warrior ships used for raiding Cargo Ship/Knarr: used for trading and carrying cargo Banished: sent away and not allowed to return to a place or country Fjords: long, narrow inlets of the sea located between steep cliffs Glaciers: large and slow-moving bodies of ice and snow that form mountains and valleys Raids: sudden attacks, often involving the stealing or taking of goods Skalds: poets who memorized the Vikings sagas (stories) and mythology and passed them down from generation to generation Thing: outdoor assembly where the Norsemen met to make decisions about their town People Ingolfur Arnarson: Norseman who left Norway with his family and settled in Iceland Erik the Red: son of Ingolfur who led the first Viking expedition to Greenland Leif Erikson: son of Erik the Red who traveled from Greenland to Newfoundland in Canada Concepts Describe everyday life of the Norse and Vikings How did living close to water influence the way Vikings lived? Connect Viking civilization to Roman civilization Sayings and Phrases Last Straw Rule the Roost Grammar Conjunctions: words that connect other words or groups of words And: means plus, along with, also But: means something different (John likes strawberry, but Jim likes chocolate.) Because: means for this reason and answers the “why” question. It signals the cause of something Suffixes: word part added to the end of the root word that changes the meaning (-ed, -ing, -er/-or, -s/-es, -ian, -ist, -y, -al, -ly, -ous) -ive: means “relating to” (inventive relating to inventing) . -

What Caused the Viking Age? Propaganda by the National Socialists and Others Between 1920 and 1945 (See Muller-Wille¨ 1994; Nondier 2002: 509-11)

What caused the Viking Age? James H. Barrett∗ This paper addresses the cause of the Viking episode in the approved Viking manner – head- on, reviewing and dismissing technical, environmental, demographic, economic, political and Research ideological prime movers. The author develops the theory that a bulge of young males in Scandinavia set out to get treasure to underpin their chances of marriage and a separate domicile. Keywords: Scandinavia, Britain, Ireland, North Sea, Viking Age, early medieval, Abbasid, treasure, silver Introduction The Scandinavian diaspora of the late eighth to mid-eleventh centuries AD known as the Viking Age was both widespread in scale and profound in impact. Long-range maritime expeditions facilitated a florescence of piracy, trade, migration, conquest and exploration across much of Europe – ultimately extending to western Asia and the eastern seaboard of northern North America (Brink & Price in press). This diaspora contributed to state formation and/or urbanism in what are now Ireland, Scotland, England, Russia and the Ukraine – not to mention within Scandinavia itself. It was one of the catalysts leading to fragmentation of the Carolingian empire and it created the semi-independent principality of Normandy. As one of the last ‘barbarian migrations’ of post-Roman Europe, it is also among the best documented. Its study is thus uniquely important for an understanding of European history. It also provides good examples of three processes of relevance to the archaeology of the wider world: the potential impact of small-scale but highly militarised non-state communities on neighbouring ‘complex societies’, the development of transnational identities in a pre- capitalist world and the seaborne colonisation of islands. -

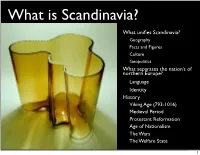

What Is Scandinavia?

What is Scandinavia? What unifies Scandinavia? Geography Facts and Figures Culture Geopolitics What separates the nation’s of northern Europe? Language Identity History Viking Age (793-1016) Medieval Period Protestant Reformation Age of Nationalism The Wars The Welfare State 1 Geography • Definining characteristics of Scandinavia’s location • Climate • Maritime access • Landmass • Forests • Not a “crossroads” • No Roman history Scandinavia on the northern margin of Europe, alongside Russia and Germany 2 Facts and Figures • Denmark • Norway • Copenhagen • Oslo • Danish • Trondheim • 5 million • Christiania • Finland • Norwegian • Helsinki • 4.5 million • Finnish/Swedish • Sweden • 5 million • Stockholm • Iceland • Göteborg • Reykjavik • Malmö • Icelandis • Swedish • 250,000 • 9 million 3 Culture • What do we mean by culture? • Organic implications • Culture as construct • “High Culture • “Anthropological culture” • Institutions as key construction sites • Unifying elements of Scandinavian culture • History • Not a part of Roman Empire • Vikings circa 800-1100 • Kalmar Union 1397-1512 • Language • Lutheran church • Constitutional Monarchies 13th-century Stavkirke, Norway • Universal welfare state 4 Geopolitics Finnish soldiers during the Continuation War, 1941-1944 • What is geopolitics? • Multiple causes for institutional (state) behavior • What relations of economics and geography together explain policy • Scandinavia on the Margins • Relatively limited sources of wealth • Small population dispersed over poor agricultural land • Location -

Norsemen and Vikings: the Culture That Inspired Decades of Fear

The 2014 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings New Orleans, USA NORSEMEN AND VIKINGS: THE CULTURE THAT INSPIRED DECADES OF FEAR Alexandra McKenna Introduction to Historiography and Method Dr. John Broom When one thinks of Vikings the mind’s eye often envisions muscular men covered in furs with large horned helmets. Thoughts of these monstrous men link themselves with words such as bloodlust, raids, and conqueror. Which leaves one to ponder why these men have come to be forever linked with such carnage, surely they must have had some redeeming qualities? Viking studies have increased in popularity during modern times. This has led many historians to pick up the sagas left behind by the Norse people, so that they may better understand the driving forces behind the decades of fear these Viking raiders inspired. What these historians have uncovered sheds new light on the Vikings, showcasing not only men of destruction, but also of enlightenment. It is widely believed that at the opening of the Viking age, Scandinavia housed a mere two million people.1 This time also saw an age of rapid population growth, which many historians and geologist alike, attribute to climate change. The warmer climate brought on during the early eighth century allowed for milder winters in the Norsemen’s cold climate.2 The warmer climate inspired the typical response of lower infant mortality rates, and a more protein rich diet that allowed for overall better health.3 It is thus feasible to believe that the overall population boom supplied the necessary push factor that inspired the Vikings to take to the sea in search of new lands. -

Viking Age Arms and Armor Originating in the Frankish Kingdom

The Hilltop Review Volume 4 Issue 2 Spring Article 8 April 2011 Viking Age Arms and Armor Originating in the Frankish Kingdom Valerie Dawn Hampton Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Hampton, Valerie Dawn (2011) "Viking Age Arms and Armor Originating in the Frankish Kingdom," The Hilltop Review: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview/vol4/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 36 VIKING AGE ARMS AND ARMOR ORIGNINATING IN THE FRANKISH KINGDOM By Valerie Dawn Hampton Department of History [email protected] The export of Carolingian arms and armor to Northern regions outside the Frankish Empire from the 9th and early 10th century is a subject which has seen a gradual increase of interest among archaeologists and historians alike. Recent research has shown that the Vikings of this period bore Frankish arms, particularly swords, received either through trade or by spolia that is plunder.1 In the examination of material remains, illustrations, and capitularies, the rea- son why Carolingian arms and armor were prized amongst the Viking nations can be ascertained and evidence found as to how the Vikings came to possess such valued items. The material remains come from a variety of archaeological sites, which have yielded arms and sometimes even well preserved armor.