Bibliography SCANDINAVIA and ICELAND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Runic Stone to Charter Transformation of Property Confirmation in 11Th and 12Th Century Denmark

From Runic Stone to Charter Transformation of property confirmation in 11th and 12th century Denmark Minoru OZAWA It has been long thought that one hundred years from the middle of the 11th century when Cnut’s empire collapsed to the year 1157 when Valdemar the Great became Danish king was a transitory age in Danish history. Some historians considered these years as an age of shift from the pagan Viking Age to the Christian Middle Ages.1 However we have to pay more attention to the century to deeply understand that various innovative shifts were progressing politically, economically, socially and culturally. My paper aims to make clear one aspect of these shifts, that is the background of the transformation of property confirmation in Denmark at the gate of the early Middle Ages. The central concern exists in how and why Denmark, non-successor state of the Roman empire, adopted the way of property confirmation through written documents into its own system of land management. 1. Runic Stone as Testimony of Property Inheritance Around 1000, building movement of impressive monuments was marking Scandinavian landscape: runic stones. A runic stone is a kind of memorial stone which the living built in memory of the deceased, with carved runes on its surface, sometimes drawn with beautiful decorative animal pictures. The earlier date of runic stones like Björketorp stone in Blekinge in present Sweden goes back to pre-Viking Age, but almost all of them were concentrated on the year 1000, the era that Scandinavian medievalists call the late Viking Age. According to a recent catalogue, approximately 500 stones in all have been discovered in Denmark, Norway and Sweden until the present times. -

Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses

Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. The present study has been based as far as possible on primary sources such as protocols, letters, legal documents, and articles in journals, magazines, and newspapers from the nineteenth century. A contextual-comparative approach was employed to evaluate the objectivity of a given source. Secondary sources have also been consulted for interpretation and as corroborating evidence, especially when no primary sources were available. The study concludes that the Pietist revival ignited by the Norwegian Lutheran lay preacher, Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771-1824), represented the culmination of the sixteenth- century Reformation in Norway, and the forerunner of the Adventist movement in that country. -

Saami and Scandinavians in the Viking

Jurij K. Kusmenko Sámi and Scandinavians in the Viking Age Introduction Though we do not know exactly when Scandinavians and Sámi contact started, it is clear that in the time of the formation of the Scandinavian heathen culture and of the Scandinavian languages the Scandinavians and the Sámi were neighbors. Archeologists and historians continue to argue about the place of the original southern boarder of the Sámi on the Scandinavian peninsula and about the place of the most narrow cultural contact, but nobody doubts that the cultural contact between the Sámi and the Scandinavians before and during the Viking Age was very close. Such close contact could not but have left traces in the Sámi culture and in the Sámi languages. This influence concerned not only material culture but even folklore and religion, especially in the area of the Southern Sámi. We find here even names of gods borrowed from the Scandinavian tradition. Swedish and Norwegian missionaries mentioned such Southern Sámi gods such as Radien (cf. norw., sw. rå, rådare) , Veralden Olmai (<Veraldar goð, Frey), Ruona (Rana) (< Rán), Horagalles (< Þórkarl), Ruotta (Rota). In Lule Sámi we find no Scandinavian gods but Scandinavian names of gods such as Storjunkare (big ruler) and Lilljunkare (small ruler). In the Sámi languages we find about three thousand loan words from the Scandinavian languages and many of them were borrowed in the common Scandinavian period (550-1050), that is before and during the Viking Age (Qvigstad 1893; Sammallahti 1998, 128-129). The known Swedish Lapponist Wiklund said in 1898 »[...] Lapska innehåller nämligen en mycket stor mängd låneord från de nordiska språken, av vilka låneord de äldsta ovillkorligen måste vara lånade redan i urnordisk tid, dvs under tiden före ca 700 år efter Kristus. -

The Viking Age

Laval University From the SelectedWorks of Fathi Habashi March, 2020 The iV king Age Fathi Habashi Available at: https://works.bepress.com/fathi_habashi/615/ The Viking Age INTRODUCTION The Viking Age (793-1066) is a period in history during which the Scandinavians expanded and built settlements throughout Europe. They are sometimes referred to as Norsemen and known to the Greek as Varangians. They took two routes: the East - - the present-day Ukraine and Russia, and the West mainly in the present-day Iceland, Greenland, Newfoundland, Normandy, Italy, and the British Isles. The Viking were competent sailors, adept in land warfare as well as at sea. Their ships were light enough to be carried over land from one river system to another. Viking ships The motivation of the Viking to invade East and West is a problem to historians. Many theories were given none was the answer. For example, retaliation against forced conversion to Christianity by Charlemagne by killing any who refused to become baptized, seeking centers of wealth, kidnapping slaves, and a decline in the profitability of old trade routes. Viking ship in Oslo Museum The Vikings raids in the East and the West of Europe VIKINGS IN THE EAST The Dnieber The Vikings of Scandinavia came by way of the Gulf of Finland and sailed up the Dvina River as far as they could go, and then carried their ships across land to the Dnieper River, which flows south to the Black Sea. They raided villages then they became interested in trading with the Slavs. Using the Dnieper, they carried shiploads of furs, honey, and wax south to markets on the Black Sea, or sailed across that sea trade in Constantinople. -

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Henrik Williams. Scripta Islandica 65/2014

Comments on Michael Lerche Nielsen’s Paper HENRIK WILLIAMS The most significant results of Michael Lerche Nielsen’s contribution are two fold: (1) There is a fair amount of interaction between Scandinavians and Western Slavs in the Late Viking Age and Early Middle Ages — other than that recorded in later medieval texts (and through archaeology), and (2) This interaction seems to be quite peaceful, at least. Lerche Nielsen’s inventory of runic inscriptions and name material with a West Slavic connection is also good and very useful. The most important evidence to be studied further is that of the place names, especially Vinderup and Vindeboder. The former is by Lerche Niel sen (p. 156) interpreted to contain vindi ‘the western Slav’ which would mean a settlement by a member of this group. He compares (p. 156) it to names such as Saxi ‘person from Saxony’, Æistr/Æisti/Æist maðr ‘person from Estonia’ and Tafæistr ‘person from Tavastland (in Finland)’. The problem here, of course, is that we do not know for sure if these persons really, as suggested by Lerche Nielsen, stem ethnically from the regions suggested by their names or if they are ethnic Scandi navians having been given names because of some connection with nonScandi navian areas.1 Personally, I lean towards the view that names of this sort are of the latter type rather than the former, but that is not crucial here. The importance of names such as Æisti is that it does prove a rather intimate connection on the personal plane between Scandinavians and nonScan dinavians. -

Chronology and Typology of the Danish Runic Inscriptions

Chronology and Typology of the Danish Runic Inscriptions Marie Stoklund Since c. 1980 a number of important new archaeological runic finds from the old Danish area have been made. Together with revised datings, based for instance on dendrochronology or 14c-analysis, recent historical as well as archaeological research, these have lead to new results, which have made it evident that the chronology and typology of the Danish rune material needed adjustment. It has been my aim here to sketch the most important changes and consequences of this new chronology compared with the earlier absolute and relative ones. It might look like hubris to try to outline the chronology of the Danish runic inscriptions for a period of nearly 1,500 years, especially since in recent years the lack of a cogent distinction between absolute and relative chronology in runological datings has been criticized so severely that one might ask if it is possible within a sufficiently wide framework to establish a trustworthy chro- nology of runic inscriptions at all. However, in my opinion it is possible to outline a chronology on an interdisciplinary basis, founded on valid non-runo- logical, external datings, combined with reliable linguistic and typological cri- teria deduced from the inscriptions, even though there will always be a risk of arguing in a circle. Danmarks runeindskrifter A natural point of departure for such a project consists in the important attempt made in Danmarks runeindskrifter (DR) to set up an outline of an overall chro- nology of the Danish runic inscriptions. The article by Lis Jacobsen, Tidsfæst- else og typologi (DR:1013–1042 cf. -

Religion Education in Norway: Tension Or Harmony Between Human Rights and Christian Cultural Heritage?

Religion Education in Norway: Tension or Harmony between Human Rights and Christian Cultural Heritage? BENGT-OVE ANDREASSEN University of Tromsø Abstract Both research and public and scholarly debate on religious education (RE) in Norway have mostly revolved around the subject in primary and secondary school called Christianity, Religion and Ethics (KRL) (later renamed Religion, Philosophies of Life and Ethics, RLE), not least due to the criticisms raised by the UN’s Human Rights Com- mittee in 2004 and the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in 2007 of the Norwegian model for RE in primary and secondary schools. The RE subject in upper secondary school, however, is hardly ever mentioned. The same applies to teacher education. This article therefore aims at providing some insight into how RE has developed in the Norwegian educational system overall, ranging from primary and secondary to upper secondary and including the different forms of teacher education. Keywords: religious education, teacher education, educational system, human rights, Norway Historical Background The development of religious education (RE) in Norway can be described in three main perspectives which link with historical periods: firstly, the Chris- tian education policy in the period from 1736 (when confirmation was made obligatory for all people) to 1860; secondly, the gradual secularisation of the school from 1860, as new subjects supplemented and challenged Christian- ity as the main curricular focus in schools, to 1969, when a new Education Act stated that RE should no longer should be confessionally rooted in Christianity. The period of religious instruction in Norwegian schools was then formally over, and ‘separative religious education’, in what has been © The Finnish Society for the Study of Religion Temenos Vol. -

The Old Potter's Almanack

The Old Potter’s Almanack Page 23 THE BRAZING OF IRON AND THE unidentified in pictures in the catalogue (cf. Gebers METALSMITH AS A SPECIALISED POTTER 1981, 120 where figs. 1 and 2 may depict fragments of brazing packages for padlocks). Anders Söderberg Sigtuna Museum Sweden Email: [email protected] Introduction In early medieval metal craft, ceramics were used for furnace and forge linings and for crucibles and containers for processing metals, processes like refining, assaying and melting. Ceramic materials were also used in processes such as box carburisation and brazing, which is more rarely paid attention to. In the latter cases, we are merely talking about tempered clay as a protective “folding material”, rather than as vessels. The leftover pieces from the processes, though, look very similar to crucible fragments, which is why the occurrence of brazing and carburisation easily gets missed when interpreting workshop sites. Yet, just like the crucibles, they tell about important processes and put Figure 1. Map of Scandinavia, Denmark, the Baltic Sea and the spotlight on the metalworkers as skilled potters. the different sites mentioned in this paper (A. Söderberg). Leftover pieces of what probably were clay What are probably the remains of fragments wrappings used in box carburisation, performed as emerging from the brazing of small bells, were found described by Theophilus in book III, chapters 18 and at Helgö and in Bosau (Figure 2; cf. Gebers 1981, 19 (Hawthorne and Smith 1979, 94–95), seem to be 120 figs. 3-6), in early Christian Clonfad in Ireland relatively common at early medieval workshop sites (Young 2005, 3; Stevens 2006, 10) and in a Gallo- in Sweden. -

Towards the Kalmar Union

S P E C I A L I Z E D A G E N C I E S TOWARDS THE KALMAR UNION Dear Delegates, Welcome to the 31st Annual North American Model United Nations 2016 at the University of Toronto! On behalf of all of the staff at NAMUN, we welcome you to the Specialized Agency branch of the conference. I, and the rest of the committee staff are thrilled to have you be a delegate in Scandinavia during the High Middle Ages, taking on this challenging yet fascinating topic on the futures of the three Scandinavian Kingdoms in a time of despair, poverty, dependence and competitiveness. This will truly be a new committee experience, as you must really delve into the history of these Kingdoms and figure out how to cooperate with each other without sending everyone into their demise. To begin, in the Towards the Kalmar Union Specialized Agency, delegates will represent influential characters from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, which include prominent knights, monarchs, nobles, and important religious figures who dominate the political, military and economic scenes of their respective Kingdoms. The impending issues that will be discussed at the meeting in Kalmar, Sweden include the future of the Danish and Norwegian crowns after the death of the sole heir to the thrones, Olaf II. Here, two distant relatives to Valdemar IV have a claim to the throne and delegates will need to decide who will succeed to the throne. The second order of business is to discuss the growing German presence in Sweden, especially in major economic cities. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

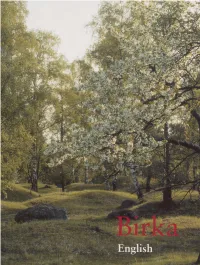

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Mwtwl ^ bfikj O Opw UmA mwfrtMs O Cme-fou ö {wert* RoA«l O "liWIøf'El'i'fcA Birka Bente Magnus National Heritage Board View from the Fort Hill towards the Black Earth and Hemlanden (“The Homelands ”) at Birka. Birka is no. 2 in the series “Cultural Monuments in Sweden”, a set of guides to some of the most interesting ancient and historic monuments in Sweden. Author: Bente Magnus wrote the original text in Norwegian Translator: Alan Crozier Editor: Gunnel Friberg Layout: Agneta Modig ©1998 National Heritage Board ISBN 91-7209-125-8 1:3 Publisher: National Heritage Board, Box 5405, SE-114 84 Stockholm, Sweden Tel +46 (0)8 5191 8000 Printed by: Halls Offset, Växjö, 2004 Aerial view of Birka, 1997. The history of a town In Lake Mälaren, about 30 kilometres west protectedlocation, it attracted people from of Stockholm, between the fjords of Södra far and near to come to offer their goods Björkfjärdenand Hovgårdsfjärden,lies the and services. Today Birka is one of Swe island of Björkö. Until 1,100 years ago, den’s sites on Unesco’s World Heritage List there was a small, busy market town on and a popular attraction for thousands of the western shore of the island. -

Church of Norway Pre

You are welcome in the Church of Norway! Contact Church of Norway General Synod Church of Norway National Council Church of Norway Council on Ecumenical and International Relations Church of Norway Sami Council Church of Norway Bishops’ Conference Address: Rådhusgata 1-3, Oslo P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway Telephone: +47 23 08 12 00 E: [email protected] W: kirken.no/english Issued by the Church of Norway National Council, Communication dept. P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway. (2016) The Church of Norway has been a folk church comprising the majority of the popu- lation for a thousand years. It has belonged to the Evangelical Lutheran branch of the Christian church since the sixteenth century. 73% of Norway`s population holds member- ship in the Church of Norway. Inclusive Church inclusive, open, confessing, an important part in the 1537. At that time, Norway Church of Norway wel- missional and serving folk country’s Christianiza- and Denmark were united, comes all people in the church – bringing the good tion, and political interests and the Lutheran confes- country to join the church news from Jesus Christ to were an undeniable part sion was introduced by the and attend its services. In all people. of their endeavor, along Danish king, Christian III. order to become a member with the spiritual. King Olav In a certain sense, the you need to be baptized (if 1000 years of Haraldsson, and his death Church of Norway has you have not been bap- Christianity in Norway at the Battle of Stiklestad been a “state church” tized previously) and hold The Christian faith came (north of Nidaros, now since that time, although a permanent residence to Norway in the ninth Trondheim) in 1030, played this designation fits best permit.