Translocation Is the Likely Driver of a Syndrome with Ambiguous Genitalia, Facial Dysmorphism, Intellectual Disability, and Speech Delay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Report a Fetus with Kabuki Syndrome 2 Detected by Chromosomal Microarray Analysis

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2020;13(2):302-306 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0104334 Case Report A fetus with Kabuki syndrome 2 detected by chromosomal microarray analysis Chen-Zhao Lin1, Bi-Ru Qi1, Jian-Su Hu2, Xiu-Qiong Huang3 Departments of 1Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2Ultrasound, 3Laboratory Medicine, Fuzhou Municipal First Hospital Affiliated to Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350009, Fujian Province, The People’s Republic of China Received November 1, 2019; Accepted January 26, 2020; Epub February 1, 2020; Published February 15, 2020 Abstract: Background: Kabuki syndrome is a rare multiple congenital anomaly syndrome characterized by distinct facial features, intellectual disability, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal abnormalities, persistence of fetal finger- tip pads, and postnatal growth deficiency. Currently, the diagnosis mainly depends on clinical manifestations and genetic testing. To date, there is no report on the identification Kabuki syndrome in fetuses using chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA). Case presentation: A fetus was identified with growth retardation and cardiovascular abnormality on color Doppler ultrasonography; however, non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) revealed a low risk and G-banding karyotyping revealed no abnormal karyotype detected. CMA identified a 1.3 Mb deletion on the X chromosome (Xp11.3) containing KDM6A, DUSP21, MIR222, MIR221 and CXorf36 genes. The fetus was diagnosed with Kabuki syndrome 2, and labor was induced. In addition, CMA detected a 1.3 Mb deletion in the chromosome Xp11.3 in the mother, which contains 5 genes namely KDM6A, DUSP21, MIR222, MIR221 and CXorf36, while no chromosomal abnormality was identified in the father. Conclusions: We report a fetus with Kabuki syndrome 2 detected using CMA. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Supplementary Table

Supporting information Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article: Supplementary Table S1: List of deregulated genes in serum of cancer patients in comparision to serum of healthy individuals (p < 0.05, logFC ≥ 1). ENTREZ Gene ID Symbol Gene Name logFC p-value q-value 8407 TAGLN2 transgelin 2 3,78 3,40E-07 0,0022 7035 TFPI tissue factor pathway inhibitor (lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor) 3,53 4,30E-05 0,022 28996 HIPK2 homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 3,49 2,50E-06 0,0066 3690 ITGB3 integrin, beta 3 (platelet glycoprotein IIIa, antigen CD61) 3,48 0,00053 0,081 7035 TFPI tissue factor pathway inhibitor (lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor) 3,45 1,80E-05 0,014 4900 NRGN neurogranin (protein kinase C substrate, RC3) 3,32 0,00012 0,037 10398 MYL9 myosin, light chain 9, regulatory 3,22 8,20E-06 0,011 3796 KIF2A kinesin heavy chain member 2A 3,14 0,00015 0,04 5476 CTSA cathepsin A 3,08 0,00015 0,04 6648 SOD2 superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial 3,07 4,20E-06 0,0077 2982 GUCY1A3 guanylate cyclase 1, soluble, alpha 3 3,07 0,0015 0,13 8459 TPST2 tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase 2 3,05 0,00043 0,074 2983 GUCY1B3 guanylate cyclase 1, soluble, beta 3 3,04 3,70E-05 0,021 145781 GCOM1 GRINL1A complex locus 3,02 0,00027 0,059 10611 PDLIM5 PDZ and LIM domain 5 2,87 1,80E-05 0,014 5567 PRKACB protein kinase, cAMP-dependent, catalytic, beta 2,85 0,0015 0,13 25907 TMEM158 transmembrane protein 158 (gene/pseudogene) 2,84 0,0068 0,27 8848 TSC22D1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 2,83 0,00058 0,084 26 351 APP amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein 2,82 0,00018 0,045 9240 PNMA1 paraneoplastic antigen MA1 2,78 0,00028 0,06 400073 C12orf76 chromosome 12 open reading frame 76 2,78 0,00069 0,091 649260 ILMN_35781 PREDICTED: Homo sapiens similar to LIM and senescent cell antigen-like domains 1 (LOC649260), mRNA. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

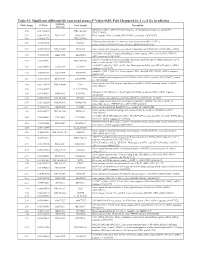

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Mapping the Landscape of Tandem Repeat Variability by Targeted Long Read Single Molecule Sequencing in Familial X-Linked Intelle

Zablotskaya et al. BMC Medical Genomics (2018) 11:123 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-018-0446-7 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Mapping the landscape of tandem repeat variability by targeted long read single molecule sequencing in familial X-linked intellectual disability Alena Zablotskaya1, Hilde Van Esch2, Kevin J. Verstrepen3, Guy Froyen4 and Joris R. Vermeesch1* Abstract Background: The etiology of more than half of all patients with X-linked intellectual disability remains elusive, despite array-based comparative genomic hybridization, whole exome or genome sequencing. Since short read massive parallel sequencing approaches do not allow the detection of larger tandem repeat expansions, we hypothesized that such expansions could be a hidden cause of X-linked intellectual disability. Methods: We selectively captured over 1800 tandem repeats on the X chromosome and characterized them by long read single molecule sequencing in 3 families with idiopathic X-linked intellectual disability. Results: In male DNA samples, full tandem repeat length sequences were obtained for 88–93% of the targets and up to 99.6% of the repeats with a moderate guanine-cytosine content. Read length and analysis pipeline allow to detect cases of > 900 bp tandem repeat expansion. In one family, one repeat expansion co-occurs with down- regulation of the neighboring MIR222 gene. This gene has previously been implicated in intellectual disability and is apparently linked to FMR1 and NEFH overexpression associated with neurological disorders. Conclusions: This study demonstrates the power of single molecule sequencing to measure tandem repeat lengths and detect expansions, and suggests that tandem repeat mutations may be a hidden cause of X-linked intellectual disability. -

A Discovery Resource of Rare Copy Number Variations in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder

INVESTIGATION A Discovery Resource of Rare Copy Number Variations in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder Aparna Prasad,* Daniele Merico,* Bhooma Thiruvahindrapuram,* John Wei,* Anath C. Lionel,*,† Daisuke Sato,* Jessica Rickaby,* Chao Lu,* Peter Szatmari,‡ Wendy Roberts,§ Bridget A. Fernandez,** Christian R. Marshall,*,†† Eli Hatchwell,‡‡ Peggy S. Eis,‡‡ and Stephen W. Scherer*,†,††,1 *The Centre for Applied Genomics, Program in Genetics and Genome Biology, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto M5G 1L7, Canada, †Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, Toronto M5G 1L7, Canada, ‡Offord Centre for Child Studies, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University, Hamilton L8P 3B6, § Canada, Autism Research Unit, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto M5G 1X8, Canada, **Disciplines of Genetics and Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland A1B 3V6, Canada, ††McLaughlin Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto M5G 1L7, Canada, and ‡‡Population Diagnostics, Inc., Melville, New York 11747 ABSTRACT The identification of rare inherited and de novo copy number variations (CNVs) in human KEYWORDS subjects has proven a productive approach to highlight risk genes for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). A rare variants variety of microarrays are available to detect CNVs, including single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays gene copy and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) arrays. Here, we examine a cohort of 696 unrelated ASD number cases using a high-resolution one-million feature CGH microarray, the majority of which were previously chromosomal genotyped with SNP arrays. Our objective was to discover new CNVs in ASD cases that were not detected abnormalities by SNP microarray analysis and to delineate novel ASD risk loci via combined analysis of CGH and SNP array cytogenetics data sets on the ASD cohort and CGH data on an additional 1000 control samples. -

Attractor Molecular Signatures and Their Applications for Prognostic Biomarkers Wei-Yi Cheng

Attractor Molecular Signatures and Their Applications for Prognostic Biomarkers Wei-Yi Cheng Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Graduate School of Arts and Science COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 c 2013 Wei-Yi Cheng All rights reserved ABSTRACT Attractor Molecular Signatures and Their Applications for Prognostic Biomarkers Wei-Yi Cheng This dissertation presents a novel data mining algorithm identifying molecular sig- natures, called attractor metagenes, from large biological data sets. It also presents a computational model for combining such signatures to create prognostic biomarkers. Us- ing the algorithm on multiple cancer data sets, we identified three such gene co-expression signatures that are present in nearly identical form in different tumor types represent- ing biomolecular events in cancer, namely mitotic chromosomal instability, mesenchymal transition, and lymphocyte infiltration. A comprehensive experimental investigation us- ing mouse xenograft models on the mesenchymal transition attractor metagene showed that the signature was expressed in the human cancer cells, but not in the mouse stroma. The attractor metagenes were used to build the winning model of a breast cancer prog- nosis challenge. When applied on larger data sets from 12 different cancer types from The Cancer Genome Atlas \Pan-Cancer" project, the algorithm identified additional pan-cancer molecular signatures, some of which involve methylation sites, microRNA expression, and protein activity. Contents List of Figures iv List of Tables vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background . 1 1.2 Previous Work on Identifying Cancer-Related Gene Signatures . 3 1.3 Contributions of the Thesis . 9 2 Attractor Metagenes 11 2.1 Derivation of an Attractor Metagene . -

Identification of Novel Hemangioblast Genes in the Early Chick Embryo

cells Communication Identification of Novel Hemangioblast Genes in the Early Chick Embryo José Serrado Marques 1, Vera Teixeira 2 ID , António Jacinto 1 and Ana Teresa Tavares 1,* ID 1 CEDOC, Chronic Diseases Research Centre, NOVA Medical School, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, Campo dos Mártires da Pátria, 130, 1169-056 Lisbon, Portugal; [email protected] (J.S.M.); [email protected] (A.J.) 2 Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência, Rua da Quinta Grande, 6, 2780-156 Oeiras, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-218-803-101 Received: 10 December 2017; Accepted: 27 January 2018; Published: 31 January 2018 Abstract: During early vertebrate embryogenesis, both hematopoietic and endothelial lineages derive from a common progenitor known as the hemangioblast. Hemangioblasts derive from mesodermal cells that migrate from the posterior primitive streak into the extraembryonic yolk sac. In addition to primitive hematopoietic cells, recent evidence revealed that yolk sac hemangioblasts also give rise to tissue-resident macrophages and to definitive hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. In our previous work, we used a novel hemangioblast-specific reporter to isolate the population of chick yolk sac hemangioblasts and characterize its gene expression profile using microarrays. Here we report the microarray profile analysis and the identification of upregulated genes not yet described in hemangioblasts. These include the solute carrier transporters SLC15A1 and SCL32A1, the cytoskeletal protein RhoGap6, the serine protease CTSG, the transmembrane receptor MRC1, the transcription factors LHX8, CITED4 and PITX1, and the previously uncharacterized gene DIA1R. Expression analysis by in situ hybridization showed that chick DIA1R is expressed not only in yolk sac hemangioblasts but also in particular intraembryonic populations of hemogenic endothelial cells, suggesting a potential role in the hemangioblast-derived hemogenic lineage. -

1 SUPPLEMENTAL DATA Figure S1. Poly I:C Induces IFN-Β Expression

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA Figure S1. Poly I:C induces IFN-β expression and signaling. Fibroblasts were incubated in media with or without Poly I:C for 24 h. RNA was isolated and processed for microarray analysis. Genes showing >2-fold up- or down-regulation compared to control fibroblasts were analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis Software (Red color, up-regulation; Green color, down-regulation). The transcripts with known gene identifiers (HUGO gene symbols) were entered into the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base IPA 4.0. Each gene identifier mapped in the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base was termed as a focus gene, which was overlaid into a global molecular network established from the information in the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base. Each network contained a maximum of 35 focus genes. 1 Figure S2. The overlap of genes regulated by Poly I:C and by IFN. Bioinformatics analysis was conducted to generate a list of 2003 genes showing >2 fold up or down- regulation in fibroblasts treated with Poly I:C for 24 h. The overlap of this gene set with the 117 skin gene IFN Core Signature comprised of datasets of skin cells stimulated by IFN (Wong et al, 2012) was generated using Microsoft Excel. 2 Symbol Description polyIC 24h IFN 24h CXCL10 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 129 7.14 CCL5 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 118 1.12 CCL5 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 115 1.01 OASL 2'-5'-oligoadenylate synthetase-like 83.3 9.52 CCL8 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 78.5 3.25 IDO1 indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 76.3 3.5 IFI27 interferon, alpha-inducible -

Oxidized Phospholipids Regulate Amino Acid Metabolism Through MTHFD2 to Facilitate Nucleotide Release in Endothelial Cells

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04602-0 OPEN Oxidized phospholipids regulate amino acid metabolism through MTHFD2 to facilitate nucleotide release in endothelial cells Juliane Hitzel1,2, Eunjee Lee3,4, Yi Zhang 3,5,Sofia Iris Bibli2,6, Xiaogang Li7, Sven Zukunft 2,6, Beatrice Pflüger1,2, Jiong Hu2,6, Christoph Schürmann1,2, Andrea Estefania Vasconez1,2, James A. Oo1,2, Adelheid Kratzer8,9, Sandeep Kumar 10, Flávia Rezende1,2, Ivana Josipovic1,2, Dominique Thomas11, Hector Giral8,9, Yannick Schreiber12, Gerd Geisslinger11,12, Christian Fork1,2, Xia Yang13, Fragiska Sigala14, Casey E. Romanoski15, Jens Kroll7, Hanjoong Jo 10, Ulf Landmesser8,9,16, Aldons J. Lusis17, 1234567890():,; Dmitry Namgaladze18, Ingrid Fleming2,6, Matthias S. Leisegang1,2, Jun Zhu 3,4 & Ralf P. Brandes1,2 Oxidized phospholipids (oxPAPC) induce endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Here we show that oxPAPC induce a gene network regulating serine-glycine metabolism with the mitochondrial methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase (MTHFD2) as a cau- sal regulator using integrative network modeling and Bayesian network analysis in human aortic endothelial cells. The cluster is activated in human plaque material and by atherogenic lipo- proteins isolated from plasma of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the MTHFD2-controlled cluster associate with CAD. The MTHFD2-controlled cluster redirects metabolism to glycine synthesis to replenish purine nucleotides. Since endothelial cells secrete purines in response to oxPAPC, the MTHFD2- controlled response maintains endothelial ATP. Accordingly, MTHFD2-dependent glycine synthesis is a prerequisite for angiogenesis. Thus, we propose that endothelial cells undergo MTHFD2-mediated reprogramming toward serine-glycine and mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism to compensate for the loss of ATP in response to oxPAPC during atherosclerosis. -

Landscape of X Chromosome Inactivation Across Human Tissues Taru Tukiainen1,2, Alexandra-Chloé Villani2,3, Angela Yen2,4, Manuel A

OPEN LETTER doi:10.1038/nature24265 Landscape of X chromosome inactivation across human tissues Taru Tukiainen1,2, Alexandra-Chloé Villani2,3, Angela Yen2,4, Manuel A. Rivas1,2,5, Jamie L. Marshall1,2, Rahul Satija2,6,7, Matt Aguirre1,2, Laura Gauthier1,2, Mark Fleharty2, Andrew Kirby1,2, Beryl B. Cummings1,2, Stephane E. Castel6,8, Konrad J. Karczewski1,2, François Aguet2, Andrea Byrnes1,2, GTEx Consortium†, Tuuli Lappalainen6,8, Aviv Regev2,9, Kristin G. Ardlie2, Nir Hacohen2,3 & Daniel G. MacArthur1,2 X chromosome inactivation (XCI) silences transcription from Given the limited accessibility of most human tissues, particularly one of the two X chromosomes in female mammalian cells to in large sample sizes, no global investigation into the impact of incom- balance expression dosage between XX females and XY males. plete XCI on X-chromosomal expression has been conducted in data- XCI is, however, incomplete in humans: up to one-third of sets spanning multiple tissue types. We used the Genotype-Tissue X-chromosomal genes are expressed from both the active and Expression (GTEx) project12,13 dataset (v6p release), which includes inactive X chromosomes (Xa and Xi, respectively) in female cells, high-coverage RNA-seq data from diverse human tissues, to investi- with the degree of ‘escape’ from inactivation varying between genes gate male–female differences in the expression of 681 X-chromosomal and individuals1,2. The extent to which XCI is shared between cells genes that encode proteins or long non-coding RNA in 29 adult tissues and tissues remains poorly characterized3,4, as does the degree to (Extended Data Table 1), hypothesizing that escape from XCI should which incomplete XCI manifests as detectable sex differences in gene typically result in higher female expression of these genes.