Global Survey of Escape from X Inactivation by RNA-Sequencing in Mouse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Escape from X Chromosome Inactivation Is an Intrinsic Property of the Jarid1c Locus

Escape from X chromosome inactivation is an intrinsic property of the Jarid1c locus Nan Lia,b and Laura Carrela,1 aDepartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and bIntercollege Graduate Program in Genetics, Pennsylvania State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033 Edited by Stanley M. Gartler, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, and approved September 23, 2008 (received for review August 8, 2008) Although most genes on one X chromosome in mammalian fe- Sequences on the X are hypothesized to propagate XCI (12) and males are silenced by X inactivation, some ‘‘escape’’ X inactivation to be depleted at escape genes (8, 9). LINE-1 repeats fit such and are expressed from both active and inactive Xs. How these predictions, particularly on the human X (8–10). Distinct dis- escape genes are transcribed from a largely inactivated chromo- tributions of other repeats classify some mouse X genes (5). some is not fully understood, but underlying genomic sequences X-linked transgenes also test the role of genomic sequences in are likely involved. We developed a transgene approach to ask escape gene expression. Most transgenes are X-inactivated, whether an escape locus is autonomous or is instead influenced by although a number escape XCI (e.g., refs. 13 and 14). Such X chromosome location. Two BACs carrying the mouse Jarid1c gene transgene studies indicate that, in addition to CTCF (6), locus and adjacent X-inactivated transcripts were randomly integrated control regions and matrix attachment sites are also not suffi- into mouse XX embryonic stem cells. Four lines with single-copy, cient to escape XCI (15, 16). -

Case Report a Fetus with Kabuki Syndrome 2 Detected by Chromosomal Microarray Analysis

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2020;13(2):302-306 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0104334 Case Report A fetus with Kabuki syndrome 2 detected by chromosomal microarray analysis Chen-Zhao Lin1, Bi-Ru Qi1, Jian-Su Hu2, Xiu-Qiong Huang3 Departments of 1Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2Ultrasound, 3Laboratory Medicine, Fuzhou Municipal First Hospital Affiliated to Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350009, Fujian Province, The People’s Republic of China Received November 1, 2019; Accepted January 26, 2020; Epub February 1, 2020; Published February 15, 2020 Abstract: Background: Kabuki syndrome is a rare multiple congenital anomaly syndrome characterized by distinct facial features, intellectual disability, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal abnormalities, persistence of fetal finger- tip pads, and postnatal growth deficiency. Currently, the diagnosis mainly depends on clinical manifestations and genetic testing. To date, there is no report on the identification Kabuki syndrome in fetuses using chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA). Case presentation: A fetus was identified with growth retardation and cardiovascular abnormality on color Doppler ultrasonography; however, non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) revealed a low risk and G-banding karyotyping revealed no abnormal karyotype detected. CMA identified a 1.3 Mb deletion on the X chromosome (Xp11.3) containing KDM6A, DUSP21, MIR222, MIR221 and CXorf36 genes. The fetus was diagnosed with Kabuki syndrome 2, and labor was induced. In addition, CMA detected a 1.3 Mb deletion in the chromosome Xp11.3 in the mother, which contains 5 genes namely KDM6A, DUSP21, MIR222, MIR221 and CXorf36, while no chromosomal abnormality was identified in the father. Conclusions: We report a fetus with Kabuki syndrome 2 detected using CMA. -

The HECT Domain Ubiquitin Ligase HUWE1 Targets Unassembled Soluble Proteins for Degradation

OPEN Citation: Cell Discovery (2016) 2, 16040; doi:10.1038/celldisc.2016.40 ARTICLE www.nature.com/celldisc The HECT domain ubiquitin ligase HUWE1 targets unassembled soluble proteins for degradation Yue Xu1, D Eric Anderson2, Yihong Ye1 1Laboratory of Molecular Biology, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; 2Advanced Mass Spectrometry Core Facility, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA In eukaryotes, many proteins function in multi-subunit complexes that require proper assembly. To maintain complex stoichiometry, cells use the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation system to degrade unassembled membrane subunits, but how unassembled soluble proteins are eliminated is undefined. Here we show that degradation of unassembled soluble proteins (referred to as unassembled soluble protein degradation, USPD) requires the ubiquitin selective chaperone p97, its co-factor nuclear protein localization protein 4 (Npl4), and the proteasome. At the ubiquitin ligase level, the previously identified protein quality control ligase UBR1 (ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component n-recognin 1) and the related enzymes only process a subset of unassembled soluble proteins. We identify the homologous to the E6-AP carboxyl terminus (homologous to the E6-AP carboxyl terminus) domain-containing protein HUWE1 as a ubiquitin ligase for substrates bearing unshielded, hydrophobic segments. We used a stable isotope labeling with amino acids-based proteomic approach to identify endogenous HUWE1 substrates. Interestingly, many HUWE1 substrates form multi-protein com- plexes that function in the nucleus although HUWE1 itself is cytoplasmically localized. Inhibition of nuclear entry enhances HUWE1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation, suggesting that USPD occurs primarily in the cytoplasm. -

Environmental Influences on Endothelial Gene Expression

ENDOTHELIAL CELL GENE EXPRESSION John Matthew Jeff Herbert Supervisors: Prof. Roy Bicknell and Dr. Victoria Heath PhD thesis University of Birmingham August 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Tumour angiogenesis is a vital process in the pathology of tumour development and metastasis. Targeting markers of tumour endothelium provide a means of targeted destruction of a tumours oxygen and nutrient supply via destruction of tumour vasculature, which in turn ultimately leads to beneficial consequences to patients. Although current anti -angiogenic and vascular targeting strategies help patients, more potently in combination with chemo therapy, there is still a need for more tumour endothelial marker discoveries as current treatments have cardiovascular and other side effects. For the first time, the analyses of in-vivo biotinylation of an embryonic system is performed to obtain putative vascular targets. Also for the first time, deep sequencing is applied to freshly isolated tumour and normal endothelial cells from lung, colon and bladder tissues for the identification of pan-vascular-targets. Integration of the proteomic, deep sequencing, public cDNA libraries and microarrays, delivers 5,892 putative vascular targets to the science community. -

The Results of an X-Chromosome Exome Sequencing Study

Open Access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009537 on 29 April 2016. Downloaded from HUWE1 mutations in Juberg-Marsidi and Brooks syndromes: the results of an X-chromosome exome sequencing study Michael J Friez,1 Susan Sklower Brooks,2 Roger E Stevenson,1 Michael Field,3 Monica J Basehore,1 Lesley C Adès,4 Courtney Sebold,5 Stephen McGee,1 Samantha Saxon,1 Cindy Skinner,1 Maria E Craig,4 Lucy Murray,3 Richard J Simensen,1 Ying Yzu Yap,6 Marie A Shaw,6 Alison Gardner,6 Mark Corbett,6 Raman Kumar,6 Matthias Bosshard,7 Barbara van Loon,7 Patrick S Tarpey,8 Fatima Abidi,1 Jozef Gecz,6 Charles E Schwartz1 To cite: Friez MJ, Brooks SS, ABSTRACT et al Strengths and limitations of this study Stevenson RE, . HUWE1 Background: X linked intellectual disability (XLID) mutations in Juberg-Marsidi syndromes account for a substantial number of males ▪ and Brooks syndromes: the Using the power of next generation sequencing, with ID. Much progress has been made in identifying results of an X-chromosome we have linked Juberg-Marsidi syndrome ( JMS) exome sequencing study. the genetic cause in many of the syndromes described and Brooks syndrome as allelic conditions. – BMJ Open 2016;6:e009537. 20 40 years ago. Next generation sequencing (NGS) ▪ This study provides better organisation to the doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015- has contributed to the rapid discovery of XLID genes field of X linked disorders by providing evidence 009537 and identifying novel mutations in known XLID genes that JMS is not caused by mutation in the ATRX for many of these syndromes. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

High-Throughput Discovery of Novel Developmental Phenotypes

High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Dickinson, M. E., A. M. Flenniken, X. Ji, L. Teboul, M. D. Wong, J. K. White, T. F. Meehan, et al. 2016. “High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes.” Nature 537 (7621): 508-514. doi:10.1038/nature19356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature19356. Published Version doi:10.1038/nature19356 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:32071918 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nature. Manuscript Author Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2017 March 14. Published in final edited form as: Nature. 2016 September 22; 537(7621): 508–514. doi:10.1038/nature19356. High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes A full list of authors and affiliations appears at the end of the article. Abstract Approximately one third of all mammalian genes are essential for life. Phenotypes resulting from mouse knockouts of these genes have provided tremendous insight into gene function and congenital disorders. As part of the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium effort to generate and phenotypically characterize 5000 knockout mouse lines, we have identified 410 Users may view, print, copy, and download text and data-mine the content in such documents, for the purposes of academic research, subject always to the full Conditions of use:http://www.nature.com/authors/editorial_policies/license.html#terms #Corresponding author: [email protected]. -

The Inactive X Chromosome Is Epigenetically Unstable and Transcriptionally Labile in Breast Cancer

Supplemental Information The inactive X chromosome is epigenetically unstable and transcriptionally labile in breast cancer Ronan Chaligné1,2,3,8, Tatiana Popova1,4, Marco-Antonio Mendoza-Parra5, Mohamed-Ashick M. Saleem5 , David Gentien1,6, Kristen Ban1,2,3,8, Tristan Piolot1,7, Olivier Leroy1,7, Odette Mariani6, Hinrich Gronemeyer*5, Anne Vincent-Salomon*1,4,6,8, Marc-Henri Stern*1,4,6 and Edith Heard*1,2,3,8 Extended Experimental Procedures Cell Culture Human Mammary Epithelial Cells (HMEC, Invitrogen) were grown in serum-free medium (HuMEC, Invitrogen). WI- 38, ZR-75-1, SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-436 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). DNA Methylation analysis. We bisulfite-treated 2 µg of genomic DNA using Epitect bisulfite kit (Qiagen). Bisulfite converted DNA was amplified with bisulfite primers listed in Table S3. All primers incorporated a T7 promoter tag, and PCR conditions are available upon request. We analyzed PCR products by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry after in vitro transcription and specific cleavage (EpiTYPER by Sequenom®). For each amplicon, we analyzed two independent DNA samples and several CG sites in the CpG Island. Design of primers and selection of best promoter region to assess (approx. 500 bp) were done by a combination of UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu) and MethPrimer (http://www.urogene.org). All the primers used are listed (Table S3). NB: MAGEC2 CpG analysis have been done with a combination of two CpG island identified in the gene core. Analysis of RNA allelic expression profiles (based on Human SNP Array 6.0) DNA and RNA hybridizations were normalized by Genotyping console. -

RBMX Is a Novel Hepatic Transcriptional Regulator of SREBP-1C Gene Response to High-Fructose Diet

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector FEBS Letters 581 (2007) 218–222 RBMX is a novel hepatic transcriptional regulator of SREBP-1c gene response to high-fructose diet Tadashi Takemotoa, Yoshihiko Nishiob,*, Osamu Sekineb, Chikako Ikeuchib, Yoshio Nagaib, Yasuhiro Maenob, Hiroshi Maegawab, Hiroshi Kimuraa, Atsunori Kashiwagib a Division of Molecular Genetics in Medicine, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Shiga University of Medical Science, Shiga 520-2192, Japan b Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Shiga University of Medical Science, Shiga 520-2192, Japan Received 24 October 2006; accepted 1 December 2006 Available online 14 December 2006 Edited by Berend Wieringa nisms by which the high-fructose diet induces SREBP-1c gene Abstract In rodents a high-fructose diet induces metabolic derangements similar to those in metabolic syndrome. Previously expression in the liver. we suggested that in mouse liver an unidentified nuclear protein We previously reported a variation of susceptibility to these binding to the sterol regulatory element (SRE)-binding protein- metabolic disorders after monitoring the effects of high-fruc- 1c (SREBP-1c) promoter region plays a key role for the re- tose diet in different mouse strains [6]. Ten strains of inbred sponse to high-fructose diet. Here, using MALDI-TOF MASS mice were separated into CBA and DBA groups according technique, we identified an X-chromosome-linked RNA binding to their response to high-fructose diet. The hepatic mRNA motif protein (RBMX) as a new candidate molecule. In electro- expression of SREBP-1c in CBA/JN mice was remarkably ele- phoretic mobility shift assay, anti-RBMX antibody displaced the vated by high-fructose diet but not in DBA/2N. -

Supplementary Table

Supporting information Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article: Supplementary Table S1: List of deregulated genes in serum of cancer patients in comparision to serum of healthy individuals (p < 0.05, logFC ≥ 1). ENTREZ Gene ID Symbol Gene Name logFC p-value q-value 8407 TAGLN2 transgelin 2 3,78 3,40E-07 0,0022 7035 TFPI tissue factor pathway inhibitor (lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor) 3,53 4,30E-05 0,022 28996 HIPK2 homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 3,49 2,50E-06 0,0066 3690 ITGB3 integrin, beta 3 (platelet glycoprotein IIIa, antigen CD61) 3,48 0,00053 0,081 7035 TFPI tissue factor pathway inhibitor (lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor) 3,45 1,80E-05 0,014 4900 NRGN neurogranin (protein kinase C substrate, RC3) 3,32 0,00012 0,037 10398 MYL9 myosin, light chain 9, regulatory 3,22 8,20E-06 0,011 3796 KIF2A kinesin heavy chain member 2A 3,14 0,00015 0,04 5476 CTSA cathepsin A 3,08 0,00015 0,04 6648 SOD2 superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial 3,07 4,20E-06 0,0077 2982 GUCY1A3 guanylate cyclase 1, soluble, alpha 3 3,07 0,0015 0,13 8459 TPST2 tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase 2 3,05 0,00043 0,074 2983 GUCY1B3 guanylate cyclase 1, soluble, beta 3 3,04 3,70E-05 0,021 145781 GCOM1 GRINL1A complex locus 3,02 0,00027 0,059 10611 PDLIM5 PDZ and LIM domain 5 2,87 1,80E-05 0,014 5567 PRKACB protein kinase, cAMP-dependent, catalytic, beta 2,85 0,0015 0,13 25907 TMEM158 transmembrane protein 158 (gene/pseudogene) 2,84 0,0068 0,27 8848 TSC22D1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 2,83 0,00058 0,084 26 351 APP amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein 2,82 0,00018 0,045 9240 PNMA1 paraneoplastic antigen MA1 2,78 0,00028 0,06 400073 C12orf76 chromosome 12 open reading frame 76 2,78 0,00069 0,091 649260 ILMN_35781 PREDICTED: Homo sapiens similar to LIM and senescent cell antigen-like domains 1 (LOC649260), mRNA. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

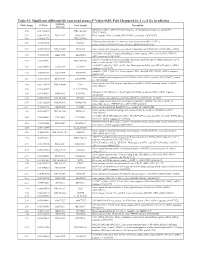

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds.