Chapter 17 Microbiology and Infectious Disease Devan Jaganath, MD, MPH, and Rebecca G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

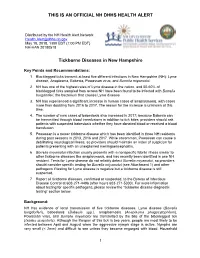

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

Use of Cell Culture in Virology for Developing Countries in the South-East Asia Region © World Health Organization 2017

USE OF CELL C USE OF CELL U LT U RE IN VIROLOGY FOR DE RE IN VIROLOGY V ELOPING C O U NTRIES IN THE NTRIES IN S O U TH- E AST USE OF CELL CULTURE A SIA IN VIROLOGY FOR R EGION ISBN: 978-92-9022-600-0 DEVELOPING COUNTRIES IN THE SOUTH-EAST ASIA REGION World Health House Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110002, India Website: www.searo.who.int USE OF CELL CULTURE IN VIROLOGY FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES IN THE SOUTH-EAST ASIA REGION © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.” Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. -

Genetic Diversity of Bartonella Species in Small Mammals in the Qaidam

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China Huaxiang Rao1, Shoujiang Li3, Liang Lu4, Rong Wang3, Xiuping Song4, Kai Sun5, Yan Shi3, Dongmei Li4* & Juan Yu2* Investigation of the prevalence and diversity of Bartonella infections in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China, could provide a scientifc basis for the control and prevention of Bartonella infections in humans. Accordingly, in this study, small mammals were captured using snap traps in Wulan County and Ge’ermu City, Qaidam Basin, China. Spleen and brain tissues were collected and cultured to isolate Bartonella strains. The suspected positive colonies were detected with polymerase chain reaction amplifcation and sequencing of gltA, ftsZ, RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB) and ribC genes. Among 101 small mammals, 39 were positive for Bartonella, with the infection rate of 38.61%. The infection rate in diferent tissues (spleens and brains) (χ2 = 0.112, P = 0.738) and gender (χ2 = 1.927, P = 0.165) of small mammals did not have statistical diference, but that in diferent habitats had statistical diference (χ2 = 10.361, P = 0.016). Through genetic evolution analysis, 40 Bartonella strains were identifed (two diferent Bartonella species were detected in one small mammal), including B. grahamii (30), B. jaculi (3), B. krasnovii (3) and Candidatus B. gerbillinarum (4), which showed rodent-specifc characteristics. B. grahamii was the dominant epidemic strain (accounted for 75.0%). Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis showed that B. grahamii in the Qaidam Basin, might be close to the strains isolated from Japan and China. -

Bartonella Henselae • Fleas and Black-Legged Ticks (Also Called Deer Ticks) of the Genus Ixodes May Serve As Vectors, but This Has Not Disease Agent: Been Proven

APPENDIX 2 Bartonella henselae • Fleas and black-legged ticks (also called deer ticks) of the genus Ixodes may serve as vectors, but this has not Disease Agent: been proven. • Bartonella henselae Blood Phase: Disease Agent Characteristics: • Agent found in endothelial cells and associated with RBCs in symptomatic cases • Gram-negative bacillus or coccobacillus, aerobic, • Occult bacteremia sometimes occurs in the absence nonmotile, nonspore-forming, facultatively intracel- of specific antibodies. lular bacterium • Order: Rhizobiales; Family: Bartonellaceae Survival/Persistence in Blood Products: • Size: 0.3-0.6 ¥ 0.3-1.0 mm • Nucleic acid: Approximately 1900 kb of DNA • A spiking study suggests that B. henselae added to RBCs can be recovered on solid media through 35 Disease Name: days of storage at 4°C. • Cat scratch disease • Cat scratch fever Transmission by Blood Transfusion: • Bacillary angiomatosis • Theoretical • Bacillary peliosis Cases/Frequency in Population: Priority Level: • 22,000 cases per year estimated in the US • Scientific/Epidemiologic evidence regarding blood • 2-6% in US blood donors safety: Theoretical • Cumulative seroprevalence of 7.1% to B. henselae and • Public perception and/or regulatory concern regard- B. quintana in US veterinary professionals ing blood safety: Absent • Public concern regarding disease agent: Very low Incubation Period: Background: • 3-10 days to appearance of papule at inoculation site; regional adenopathy may follow after a few weeks • In 1909,ALBartondescribed organisms that adhered to RBCs. Likelihood of Clinical Disease: • The name Bartonella bacilliformis was used for the • Relatively benign and self-limiting, lasting 6-12 weeks only member of the group identified before 1993. in the absence of antibiotic therapy • Several other species of Bartonella are known to infect humans, but at present, B. -

Pdfs/ Ommended That Initial Cultures Focus on Common Pathogens, Pscmanual/9Pscssicurrent.Pdf)

Clinical Infectious Diseases IDSA GUIDELINE A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiologya J. Michael Miller,1 Matthew J. Binnicker,2 Sheldon Campbell,3 Karen C. Carroll,4 Kimberle C. Chapin,5 Peter H. Gilligan,6 Mark D. Gonzalez,7 Robert C. Jerris,7 Sue C. Kehl,8 Robin Patel,2 Bobbi S. Pritt,2 Sandra S. Richter,9 Barbara Robinson-Dunn,10 Joseph D. Schwartzman,11 James W. Snyder,12 Sam Telford III,13 Elitza S. Theel,2 Richard B. Thomson Jr,14 Melvin P. Weinstein,15 and Joseph D. Yao2 1Microbiology Technical Services, LLC, Dunwoody, Georgia; 2Division of Clinical Microbiology, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; 3Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut; 4Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland; 5Department of Pathology, Rhode Island Hospital, Providence; 6Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; 7Department of Pathology, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Georgia; 8Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; 9Department of Laboratory Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio; 10Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Michigan; 11Dartmouth- Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire; 12Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky; 13Department of Infectious Disease and Global Health, Tufts University, North Grafton, Massachusetts; 14Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, Illinois; and 15Departments of Medicine and Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey Contents Introduction and Executive Summary I. -

Bartonella Henselae Detected in Malignant Melanoma, a Preliminary Study

pathogens Article Bartonella henselae Detected in Malignant Melanoma, a Preliminary Study Marna E. Ericson 1, Edward B. Breitschwerdt 2 , Paul Reicherter 3, Cole Maxwell 4, Ricardo G. Maggi 2, Richard G. Melvin 5 , Azar H. Maluki 4,6 , Julie M. Bradley 2, Jennifer C. Miller 7, Glenn E. Simmons, Jr. 5 , Jamie Dencklau 4, Keaton Joppru 5, Jack Peterson 4, Will Bae 4, Janet Scanlon 4 and Lynne T. Bemis 5,* 1 T Lab Inc., 910 Clopper Road, Suite 220S, Gaithersburg, MD 20878, USA; [email protected] 2 Intracellular Pathogens Research Laboratory, Comparative Medicine Institute, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27607, USA; [email protected] (E.B.B.); [email protected] (R.G.M.); [email protected] (J.M.B.) 3 Dermatology Clinic, Truman Medical Center, University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Dermatology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (A.H.M.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (J.P.); [email protected] (W.B.); [email protected] (J.S.) 5 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Duluth Campus, Medical School, University of Minnesota, Duluth, MN 55812, USA; [email protected] (R.G.M.); [email protected] (G.E.S.J.); [email protected] (K.J.) 6 Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, University of Kufa, Kufa 54003, Iraq 7 Galaxy Diagnostics Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC 27709, USA; [email protected] Citation: Ericson, M.E.; * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-720-560-0278; Fax: +1-218-726-7906 Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Reicherter, P.; Maxwell, C.; Maggi, R.G.; Melvin, Abstract: Bartonella bacilliformis (B. -

Induction and Resuscitation of Viable but Nonculturable Corynebacterium Diphtheriae

microorganisms Communication Induction and Resuscitation of Viable but Nonculturable Corynebacterium diphtheriae Takashi Hamabata 1, Mitsutoshi Senoh 2,*, Masaaki Iwaki 3, Ayae Nishiyama 1, Akihiko Yamamoto 3 and Keigo Shibayama 2 1 Research Institute, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo 162-8655, Japan; [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (A.N.) 2 Department of Bacteriology II, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo 208-0011, Japan; [email protected] 3 Management Department of Biosafety and Laboratory Animal, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo 208-0011, Japan; [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (A.Y.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-42-561-0771 Abstract: Many pathogenic bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae, can become vi- able but nonculturable (VBNC) following exposure to specific stress conditions. Corynebacterium diphtheriae, a known human pathogen causing diphtheria, has not previously been shown to enter the VBNC state. Here, we report that C. diphtheriae can become VBNC when exposed to low tem- peratures. Morphological differences in culturable and VBNC C. diphtheriae were examined using scanning electron microscopy. Culturable cells presented with a typical rod-shape, whereas VBNC cells showed a distorted shape with an expanded center. Cells could be transitioned from VBNC to culturable following treatment with catalase. This was further evaluated via RNA sequence-based transcriptomic analysis and reverse-transcription quantitative PCR of culturable, VBNC, and resusci- Citation: Hamabata, T.; Senoh, M.; tated VBNC cells following catalase treatment. As expected, many genes showed different behavior Iwaki, M.; Nishiyama, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Shibayama, K. -

Human Microbiota Network: Unveiling Potential Crosstalk Between the Different Microbiota Ecosystems and Their Role in Health and Disease

nutrients Review Human Microbiota Network: Unveiling Potential Crosstalk between the Different Microbiota Ecosystems and Their Role in Health and Disease Jose E. Martínez †, Augusto Vargas † , Tania Pérez-Sánchez , Ignacio J. Encío , Miriam Cabello-Olmo * and Miguel Barajas * Biochemistry Area, Department of Health Science, Public University of Navarre, 31008 Pamplona, Spain; [email protected] (J.E.M.); [email protected] (A.V.); [email protected] (T.P.-S.); [email protected] (I.J.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.C.-O.); [email protected] (M.B.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: The human body is host to a large number of microorganisms which conform the human microbiota, that is known to play an important role in health and disease. Although most of the microorganisms that coexist with us are located in the gut, microbial cells present in other locations (like skin, respiratory tract, genitourinary tract, and the vaginal zone in women) also play a significant role regulating host health. The fact that there are different kinds of microbiota in different body areas does not mean they are independent. It is plausible that connection exist, and different studies have shown that the microbiota present in different zones of the human body has the capability of communicating through secondary metabolites. In this sense, dysbiosis in one body compartment Citation: Martínez, J.E.; Vargas, A.; may negatively affect distal areas and contribute to the development of diseases. Accordingly, it Pérez-Sánchez, T.; Encío, I.J.; could be hypothesized that the whole set of microbial cells that inhabit the human body form a Cabello-Olmo, M.; Barajas, M. -

Rickettsia Felis, Bartonella Henselae, and B. Clarridgeiae, New Zealand

LETTERS Richard Reithinger,*† domestic and wild animals that also products obtained by PCR with Khoksar Aadil,† Samad Hami,† feeds readily on people. Recent stud- primers for the 17-kDa protein (4), and Jan Kolaczinski*† ies have implicated the cat flea as a citrate synthase (4), and PS 120 pro- *London School of Hygiene and Tropical vector of new and emerging infectious tein (5) genes. R. felis has been estab- Medicine, London, United Kingdom; and diseases (1). To determine the lished in tissue culture (XTC-2 and †HealthNet International, Peshawar, pathogens in C. felis in New Zealand, Vero cells) (6), and serologic testing Pakistan we collected 3 cat fleas from each of has been used to diagnose infections 11 dogs and 21 cats at the Massey (5). Reports indicate that patients References University Veterinary Teaching respond rapidly to doxycycline thera- 1. Ashford R, Kohestany K, Karimzad M. Hospital from May to June 2003. The py (5), and in vitro studies have Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kabul: observa- fleas were stored in 95% alcohol until shown the organism is susceptible to tions on a prolonged epidemic. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1992;86:361–71. they were identified by using morpho- rifampin, thiamphenicol, and fluoro- 2. Griffiths WDA. Old World cutaneous leish- logic criteria and washed in sterile quinolones. maniasis. In: Peters W, Killick-Kendrick R, phosphate-buffered saline. The DNA B. henselae is an agent of cat- editors. The leishmaniases in biology and from each flea was extracted individ- scratch disease, bacillary angiomato- medicine. London: Academic Press; 1987. p. 617–43. ually by using the QiaAmp Tissue Kit sis, bacillary peliosis, endocarditis, 3. -

Microbial Community and Vibrio Parahaemolyticus Population Dynamics in Relayed Oysters

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 2017 MICROBIAL COMMUNITY AND VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS POPULATION DYNAMICS IN RELAYED OYSTERS Michael Anthony Taylor University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Taylor, Michael Anthony, "MICROBIAL COMMUNITY AND VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS POPULATION DYNAMICS IN RELAYED OYSTERS" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 2288. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2288 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICROBIAL COMMUNITY AND VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS POPULATION DYNAMICS IN RELAYED OYSTERS BY MICHAEL ANTHONY TAYLOR BS, University of New Hampshire, 2002 Master’s Degree, University of New Hampshire, 2005 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Microbiology September, 2017 This dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Microbiology by: Dissertation Director, Stephen H. Jones Research Associate Professor, Natural Resources and the Environment Cheryl A. Whistler, Associate Professor, Molecular, Cellular & Biomedical Sciences Vaughn S. Cooper, Associate Professor, Microbiology & Molecular Genetics, University of Pittsburg School of Medicine Kirk Broders, Assistant Professor, Plant Pathology, Colorado State University College of Agricultural Sciences Thomas Howell, President / Owner, Spinney Creek Shellfish, Inc., Eliot, Maine On March 24, 2017 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Laboratory Diagnostics of Rickettsia Infections in Denmark 2008–2015

biology Article Laboratory Diagnostics of Rickettsia Infections in Denmark 2008–2015 Susanne Schjørring 1,2, Martin Tugwell Jepsen 1,3, Camilla Adler Sørensen 3,4, Palle Valentiner-Branth 5, Bjørn Kantsø 4, Randi Føns Petersen 1,4 , Ole Skovgaard 6,* and Karen A. Krogfelt 1,3,4,6,* 1 Department of Bacteria, Parasites and Fungi, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.T.J.); [email protected] (R.F.P.) 2 European Program for Public Health Microbiology Training (EUPHEM), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), 27180 Solnar, Sweden 3 Scandtick Innovation, Project Group, InterReg, 551 11 Jönköping, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Virus and Microbiological Special Diagnostics, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 5 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 6 Department of Science and Environment, Roskilde University, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark * Correspondence: [email protected] (O.S.); [email protected] (K.A.K.) Received: 19 May 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 19 June 2020 Abstract: Rickettsiosis is a vector-borne disease caused by bacterial species in the genus Rickettsia. Ticks in Scandinavia are reported to be infected with Rickettsia, yet only a few Scandinavian human cases are described, and rickettsiosis is poorly understood. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of rickettsiosis in Denmark based on laboratory findings. We found that in the Danish individuals who tested positive for Rickettsia by serology, the majority (86%; 484/561) of the infections belonged to the spotted fever group. -

Bartonella Henselae

Maggi et al. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:101 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/6/1/101 RESEARCH Open Access Bartonella henselae bacteremia in a mother and son potentially associated with tick exposure Ricardo G Maggi1,3*, Marna Ericson2, Patricia E Mascarelli1, Julie M Bradley1 and Edward B Breitschwerdt1 Abstract Background: Bartonella henselae is a zoonotic, alpha Proteobacterium, historically associated with cat scratch disease (CSD), but more recently associated with persistent bacteremia, fever of unknown origin, arthritic and neurological disorders, and bacillary angiomatosis, and peliosis hepatis in immunocompromised patients. A family from the Netherlands contacted our laboratory requesting to be included in a research study (NCSU-IRB#1960), designed to characterize Bartonella spp. bacteremia in people with extensive arthropod or animal exposure. All four family members had been exposed to tick bites in Zeeland, southwestern Netherlands. The mother and son were exhibiting symptoms including fatigue, headaches, memory loss, disorientation, peripheral neuropathic pain, striae (son only), and loss of coordination, whereas the father and daughter were healthy. Methods: Each family member was tested for serological evidence of Bartonella exposure using B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii genotypes I-III, B. henselae and B. koehlerae indirect fluorescent antibody assays and for bacteremia using the BAPGM enrichment blood culture platform. Results: The mother was seroreactive to multiple Bartonella spp. antigens and bacteremia was confirmed by PCR amplification of B. henselae DNA from blood, and from a BAPGM blood agar plate subculture isolate. The son was not seroreactive to any Bartonella sp. antigen, but B. henselae DNA was amplified from several blood and serum samples, from BAPGM enrichment blood culture, and from a cutaneous striae biopsy.