Every Day Is Halloween: a Goth Primer for Law Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sexual Vampire

Hugvísindasvið Vampires in Literature The attraction of horror and the vampire in early and modern fiction Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Magndís Huld Sigmarsdóttir Maí 2011 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska Vampires in literature The attraction of horror and the vampire in early and modern fiction Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Magndís Huld Sigmarsdóttir Kt.: 190882-4469 Leiðbeinandi: Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir Maí 2011 1 2 Summary Monsters are a big part of the horror genre whose main purpose is to invoke fear in its reader. Horror gives the reader the chance to escape from his everyday life, into the world of excitement and fantasy, and experience the relief which follows when the horror has ended. Vampires belong to the literary tradition of horror and started out as monsters of pure evil that preyed on the innocent. Count Dracula, from Bram Stoker‘s novel Dracula (1897), is an example of an evil being which belongs to the class of the ―old‖ vampire. Religious fears and the control of the church were much of what contributed to the terrors which the old vampire conveyed. Count Dracula as an example of the old vampire was a demonic creature who has strayed away from Gods grace and could not even bear to look at religious symbols such as the crucifix. The image of the literary vampire has changed with time and in the latter part of the 20th century it has lost most of its monstrosity and religious connotations. The vampire‘s popular image is now more of a misunderstood troubled soul who battles its inner urges to harm others, this type being the ―new‖ vampire. -

6.4. of Goths and Salmons: a Practice-Basedeexploration of Subcultural Enactments in 1980S Milan

6.4. Of goths and salmons: A practice-basedeExploration of subcultural enactments in 1980s Milan Simone Tosoni1 Abstract The present paper explores, for the first time, the Italian appropriations of British goth in Italy, and in particular in the 1980s in Milan. Adopting a practice-based approach and a theoretical framework based on the STS-derived concept of “enactment”, it aims at highlighting the coexistence of different forms of subcultural belonging. In particular, it identifies three main enactments of goth in the 1980s in Milan: the activist enactment introduced by the collective Creature Simili (Kindred Creatures); the enactment of the alternative music clubs and disco scene spread throughout northern Italy; and a third one, where participants enacted dark alone or in small groups. While these three different variations of goth had the same canon of subcultural resources in common (music, style, patterns of cultural consumption), they differed under relevant points of view, such as forms of socialization, their stance on political activism, identity construction processes and even the relationship with urban space. Yet, contrary to the stress on individual differences typical of post-subcultural theories, the Milanese variations of goth appear to have been socially shared and connected to participation in different and specific sets of social practices of subcultural enactment. Keywords: goth, subculture, enactment, practices, canon, scene, 1980s. For academic research, the spectacular subcultures (Hebdidge, 1979) in the 1980s in Italy are essentially uncharted waters (Tosoni, 2015). Yet, the topic deserves much more sustained attention. Some of these spectacular youth expressions, in fact, emerged in Italy as a peculiarity of the country, and are still almost ignored in the international debate. -

The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by Leeds Beckett Repository The Strange and Spooky Battle over Bats and Black Dresses: The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture Professor Karl Spracklen (Leeds Metropolitan University, UK) and Beverley Spracklen (Independent Scholar) Lead Author Contact Details: Professor Karl Spracklen Carnegie Faculty Leeds Metropolitan University Cavendish Hall Headingley Campus Leeds LS6 3QU 44 (0)113 812 3608 [email protected] Abstract From counter culture to subculture to the ubiquity of every black-clad wannabe vampire hanging around the centre of Western cities, Goth has transcended a musical style to become a part of everyday leisure and popular culture. The music’s cultural terrain has been extensively mapped in the first decade of this century. In this paper we examine the phenomenon of the Whitby Goth Weekend, a modern Goth music festival, which has contributed to (and has been altered by) the heritage tourism marketing of Whitby as the holiday resort of Dracula (the place where Bram Stoker imagined the Vampire Count arriving one dark and stormy night). We examine marketing literature and websites that sell Whitby as a spooky town, and suggest that this strategy has driven the success of the Goth festival. We explore the development of the festival and the politics of its ownership, and its increasing visibility as a mainstream tourist destination for those who want to dress up for the weekend. By interviewing Goths from the north of England, we suggest that the mainstreaming of the festival has led to it becoming less attractive to those more established, older Goths who see the subculture’s authenticity as being rooted in the post-punk era, and who believe Goth subculture should be something one lives full-time. -

Voices of the Vampire Community

VVoices of the VVampire CCommunity www.veritasvosliberabit.com/vvc.html Vampire Community Reformation Questionnaire November 14, 2013 – November 24, 2013 The purpose of this questionnaire is to objectively evaluate the current state of the Vampire Community through the process of a candid disclosure of perceived problems and to examine the individual needs of self-identified real vampi(y)res and how to best address them. Acknowledgements: The Voices of the Vampire Community (VVC) would like to thank the 169 respondents to this questionnaire and encourage constructive discussions based on the opinions and ideas offered for review. Responses were collected by Merticus of the VVC on November 24, 2013 and made publicly available to the vampire community on November 25, 2013. The responses to this questionnaire were solicited from dozens of ‘real vampire’ related websites, groups, forums, mailing lists, and social media outlets and do not necessarily represent the views of the VVC or its members. The VVC assumes no responsibility over the use, interpretation, or accuracy of responses and claims made by those who chose to participate. This document may be reproduced and transmitted for non-commercial use without permission provided there are no modifications. Vampire Community Reformation Questionnaire Voices of the Vampire Community (VVC); Copyright 2013 Response 001 1. Summarizing The Vampire Community: The community is ever evolving, but much too slow due to the egos of those that have been here the longest some times. Knowledge must be shared. 2. Specific Issues & Problems: a. The shunning of Ronin. b. Elitism among elders. c. Baby bat syndrome. 3. Participation Level: Active Participant 4. -

Punk and Counter Culture List

Punk & Counter Culture Short List Lux Mentis, Booksellers 1: Alien Sex Fiend [Concert Handbill]. Philadelphia, PA: Nature Boy Productions, 1989. Lux Mentis specializes in fine press, fine bindings, and First Edition. Bright and clean. Orange paper, black esoterica in all areas, books that have been treasured and ink lettering and pictorial elements. 8vo. np. Illus. (b/ will continue to be treasured. As a primary focus is the building and/or deaccessioning of private collections, our w plates). Fine. Broadside. (#9910) $100.00 selections are diverse and constantly evolving. If we do not have what you are seeking, please contact us and we will "Alive at Last... // First US Tour in Five Years." Held strive to find it. All items are subject to prior sale. Shipping November 14 at Revival in Philly, it was a 'split and handling is calculated on a per order basis. Please do level' show (all ages upstairs and bar down). Held in not hesitate to contact us regarding terms and/or with any conjunction with the release of Too Much Acid? Very questions or concerns. scarce. One of our focus areas revolves around the punk/anarcho sub-culture and counter culture more broadly. Presented 2. Anarchy [does not equal] Chaos // Anarchy here is a small, diverse collection of books, zines, posters, [equals] A Social Order. Australia: [Anarchism etc. all of which are grounded in one or more counter Australia], nd [circa 1977]. First Printing. Minor culture scenes. Please note, while priced separately, the edge wear, tape remains at the four corners [text Australian anarcho/punk posters are available as a small side], else bright and clean. -

Where's My Jet Pack?

Where's My Jet Pack? Online Communication Practices and Media Frames of the Emergent Voluntary Cyborg Subculture By Tamara Banbury A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Legal Studies Faculty of Public Affairs Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2019 Tamara Banbury Abstract Voluntary cyborgs embed technology into their bodies for purposes of enhancement or augmentation. These voluntary cyborgs gather in online forums and are negotiating the elements of subculture formation with varying degrees of success. The voluntary cyborg community is unusual in subculture studies due to the desire for mainstream acceptance and widespread adoption of their practices. How voluntary cyborg practices are framed in media articles can affect how cyborgian practices are viewed and ultimately, accepted or denied by those outside the voluntary cyborg subculture. Key Words: cyborg, subculture, implants, community, technology, subdermal, chips, media frames, online forums, voluntary ii Acknowledgements The process of researching and writing a thesis is not a solo endeavour, no matter how much it may feel that way at times. This thesis is no exception and if it weren’t for the advice, feedback, and support from a number of people, this thesis would still just be a dream and not a reality. I want to acknowledge the institutions and the people at those institutions who have helped fund my research over the last year — I was honoured to receive one of the coveted Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarships for master’s students from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. -

A Journal of the Radical Gothic

issue #1 gracelessa journal of the radical gothic And the ground we walk is sacred And every object lives And every word we speak Will punish or forgive And the light inside your body Will shine through history Set fire to every prison Set every dead man free “The Sound Of Freedom” Swans cover photograph by Holger Karas GRACELESS Issue one, published in February 2011 Contributors and Editors: Libby Bulloff (www.exoskeletoncabaret. com), Kathleen Chausse, Jenly, Enola Dismay, Johann Elser, Holger Karas (www. seventh-sin.de), Margaret Killjoy (www. birdsbeforethestorm.net). Graceless can be contacted at: www.graceless.info [email protected] This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to: Creative Commons 171 Second Street, Suite 300 San Francisco, California, 94105 USA What this license means is that you are free (and encouraged) to take any content from Graceless and re-use it in part or whole, or make your own work that incorporates ours, as long as you: attribute the creator of the work, share the work with the same license, and are using the product non-commercially. Note that there is a photograph that is marked as copyright to its creator, which was used with permission and may not be included in derivative works. We have chosen a Creative Commons licensing because we believe in free cultural exchange but intend to limit the power of capitalism to co-opt our work for its twisted ends. -

Post-Millennial Gothic: Comedy, Romance and the Rise of Happy Gothic

139 Post-Millennial Gothic: Comedy, Romance and the Rise of Happy Gothic Catherine Spooner Sandra Mills, University of Hull London: Bloomsbury, 2017 ISBN: 9781441101211, 213pp. £21.99 Don’t judge a book by its cover, or so the old adage goes; when it comes to Catherine Spooner’s most recent publication, Post-Millennial Gothic: Comedy, Romance and the Rise of Happy Gothic, though, it is hard not to. The eye-catching cover, with whimsically macabre illustrations created by artist Alice Marwick, features an array of familiar contemporary Gothic figures; the Twilight (2008-2012) saga’s Edward and Bella, Tim Burton’s Mad Hatter, and The Mighty Boosh (2003-2007) logo all feature alongside more traditional iconography of the genre: bats, dolls, ravens, roses, and skulls. Spooner is a respected authority on the Gothic and has, over the years, published extensively on the genre across two monographs: Fashioning Gothic Bodies (2004) and Contemporary Gothic (2006), countless chapters, articles, edited collections, and exhibition catalogues. Post-Millennial Gothic is a welcome addition to this growing collection. Post-Millennial Gothic charts the pervasive spread of the Gothic in post-millennial culture, showing that contemporary Gothic is often humorous, romantic, and increasingly, as Spooner deftly demonstrates, happy. Spooner surveys an eclectically comprehensive mix of narratives from iconic Gothic texts: Frankenstein (1818), Wuthering Heights (1847), Dracula (1897); to more recent cult films: The Breakfast Club (1985), The Lost Boys (1987), Edward Scissorhands (1990); serialized sitcoms: The IT Crowd (2006-2013), The Big Bang Theory (2007-), Being Human (2011-2014); supernatural series: Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1996- 2003), Supernatural (2005-), True Blood (2008-2014); and makeover shows: Grand Designs (1999-), Queer Eye for the Straight Guy (2003-2007), Snog Marry Avoid (2008-2013). -

Breathers and Suckers: Sources of Queerness in True Blood

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Aleš Rumpel Breathers and Suckers: Sources of Queerness in True Blood Bachelor‘s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2011 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. Acknowledgement I would like to thank the thesis supervisor Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A., and Mgr. Kateřina Kolářová, PhD., for support and inspiration, and also to my friend Zuzana Bednářová and my husband Josef Rabara for introducing me to the world of True Blood. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Queer Reading ant the Heteronormative Text ....................................................................... 4 Contextualising True Blood ....................................................................................................... 8 Strangers to prime-time ......................................................................................................... 8 Erecting and penetrating: vampire as a metaphor for queer sexuality ........................ 17 ―We are not monsters. We are Americans‖ .......................................................................... 28 Deviant lifestyle ..................................................................................................................... 30 God hates -

Understanding Youth and Culture

Module 4 ‐ Understanding Youth and Culture Subcultures: definitions Look at the list of some subcultures that are observed in youth culture around the world1. Punk The punk subculture is based around punk rock. It emerged from the larger rock music scene in the mid‐to‐late‐1970s in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and Japan. The punk movement has spread around the globe and developed into a number of different forms. Punk culture encompasses distinct styles of music, ideologies, fashion, visual art, dance, literature, and film. Punk also lays claim to a lifestyle and community. Biker Around the world, motorcycles have historically been associated with subcultures. Some of these subcultures have been loose‐knit social groups such as the cafe racers of 1950s Britain, and the Mods and Rockers of the 1960s. A few are believed to be criminal gangs. Social motorcyclist organisations are popular and are sometimes organised geographically, focus on individual makes, or even specific models. Many motorcycle organisations raise money for charities through organised events and rides. Some organisations hold large international motorcycle rallies in different parts of the world that are attended by many thousands of riders. Bōsōzoku (暴走族 "violent running gang") is a Japanese subculture associated with motorcycle clubs and gangs. They were first seen in the 1950s as the Japanese automobile industry expanded rapidly. The first bōsōzoku were known as kaminari‐zoku (雷族 "Lightning Tribes"). It is common to see bōsōzoku groups socializing in city centres and playing loud music characterized by their lifestyle, such as The Roosters, and the Street Sliders. -

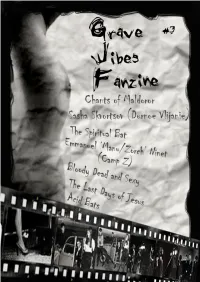

Grave Gibes Fanzine #3 Table of Contents

Grave Gibes Fanzine #3 Table of contents Interview with ‘The Last Days of Jesus’ 3 Interview with Acid Bats. 6 Interview with Bloody, Dead & Sexy (Rosa Iahn) 10 Emmanuel ‘Manu/Zorch’ Ninet 14 Interview with ‘The Spiritual Bat’. 19 The Spiritual Bat – Through the Shadows review 23 Interview with Sasha Skvortsov (Durnoe Vlijanie) 25 Interview with Loren (Chants of Maldoror). 30 2 Interview with ‘The Last Days of Jesus’ http://www.myspace.com/thelastdaysofjesus/ http://www.thelastdaysofjesus.sk/ TLDOJ, Cartoon by Stefan Andrejco TLDOJ, 2003, Photo by Jozef Barinka Nattsol: As I know, you took a part in the foundation of the ‘goth’ scene in Slovakia. How did it grow up? Tell me more about your activity there. And how did you face ‘goth’ music? Mary0: Well, I don’t know what to say… I work for the scene here in Slvakia more than 15 years. In the beginning there were the parties, then the fanzine/magazine called Stigma, radio show in the local radio station, concerts and so on. It’s a long time and a lot of work was done inbetween. Nattsol: Tell me more about Batcave.sk. What is it actually? Mary0: Actually it’s more or less just the monthly party including Live acts. However, we’re working on new visual of the webzine at the moment. Well, it’s always a question of time to work on the projects like tis. Especially when one has a family and regular job. Then the priorities change a bit… 3 Nattsol: The next question is just to Mary0. -

April 07, 2008 ARTIST PORTER WAGONER TITLE the Cold Hard Facts of Life LABEL Bear Family Records CATALOG # BCD 16537 PRICE-CODE CH EAN-CODE

SHIPPING DATE: March 17, 2008 (estimated) STREET DATE: April 07, 2008 ARTIST PORTER WAGONER TITLE The Cold Hard Facts Of Life LABEL Bear Family Records CATALOG # BCD 16537 PRICE-CODE CH EAN-CODE 4000127 165374 ISBN-CODE 978-3-89916-381-0 FORMAT 3-CD digipac with 60-page booklet GENRE Country TRACKS 70 PLAYING TIME 176:57 KEY SELLING POINTS • First CD release of six best-selling concept albums that gave the late country music superstar Porter Wagoner a cult following: 'Confessions Of A Broken Man' (1966); 'Soul Of A Convict' (1967); 'The Cold Hard Facts Of Life' (1967); 'The Bottom Of A Bottle' (1968); 'The Carroll County Accident' (1969); and 'Down In The Alley – Skid Row Joe' (1970). • Seventy gripping 'slice of life' songs and recitations including such memorable Top 5 'Billboard' country chart hits as Green, Green Grass Of Home; Skid Row Joe; The Cold Hard Facts Of Life; and The Carroll County Accident . • Features a rogue's gallery of murderers, philanderers, depressives, death-row inmates, unrepentant barflies, panhandling winos and other losers. • Includes extensive notes covering these fascinating albums and Wagoner's life and career. SALES NOTES Invigorated by a critically acclaimed new album, invitations to open at major venues for Neko Case and The White Stripes, and a guest appearance on CBS-TV's 'The Late Show with David Letterman,' country music icon Porter Wagoner was riding on a late-career resurgence when he died October 26, 2007 after a brief illness. Mainstream audiences best knew the lanky, rhinestone-suited singer as a symbol of 'old Nashville' and a longtime member of The Grand Ole Opry.