Identifying the Dead of Tyne Cot by Peter Hodgkinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passchendaele Archives

Research workshop Passchendaele Archives This workshop is based on the "Passchendaele Archives", a project of the Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917 that tries to give the many names in the cemeteries and monuments a story and a face. To make a visit to CWGC Tyne Cot Cemetery tangible for students, during this workshop they conduct their own research in the education room of the MMP1917 starting with a photo, name and date of death. They try to reconstruct and map what happened on the fatal day of “their” fallen soldier. After the workshop, students can find the grave or memorial of the soldier at CWGC Tyne Cot Cemetery. They now possess a personal story behind the endless rows of names, in the cemetery. This bundle provides practical information about this educational package that enriches a classroom visit to the museum and Tyne Cot Cemetery. Content of this information bundle: - Connection with curricula – p. 1 - Practical information – p. 2 - The research workshop – p. 3 - Personal records – p. 5 - In the area – p. 8 Connection with curricula: The Passchendaele Archives research workshop and the accompanying educational package mainly focus on the following subjects: • History, in particular WWI (theme) • English (source material) The content of this package is consistent with multiple history program curricula. It places personal stories related to WWI in a wider context as the full educational package interfaces with ideas, imperialism, norms and values that were present in the wider 19th and early 20th century British Empire. In addition, mathematics and geography skills are also used the workshop, giving it a multidisciplinary approach. -

Of Victoria Cross Recipients by New South Wales State Electorate

Index of Victoria Cross Recipients by New South Wales State Electorate INDEX OF VICTORIA CROSS RECIPIENTS BY NEW SOUTH WALES STATE ELECTORATE COMPILED BY YVONNE WILCOX NSW Parliamentary Research Service Index of Victoria Cross recipients by New South Wales electorate (includes recipients who were born in the electorate or resided in the electorate on date of enlistment) Ballina Patrick Joseph Bugden (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 36 Balmain William Mathew Currey (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 92 John Bernard Mackey (WWII) born ......................................................................... 3 Joseph Maxwell (WWII) born .................................................................................. 5 Barwon Alexander Henry Buckley (WWI) born, resided on enlistment ................................. 8 Arthur Charles Hall (WWI) resided on enlistment .................................................... 26 Reginald Roy Inwood (WWI) resided on enlistment ................................................ 33 Bathurst Blair Anderson Wark (WWI) born ............................................................................ 10 John Bernard Mackey (WWII) resided on enlistment .............................................. ..3 Cessnock Clarence Smith Jeffries (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 95 Clarence Frank John Partridge (WWII) born........................................................................... 13 -

Tyne Cot Cemetery Beschrijving

Tyne Cot Cemetery Beschrijving Beschrijving Locatie Gelegen tussen de Tynecotstraat en de Vijfwegenstraat, op de W-zijde van een heuvelrug, ca. 2,5km ten ZW van het dorp Passendale. Het omliggende landbouwgebied is heuvelachtig. De begraafplaats bevat verschillende bunkers, waaronder 1 vooraan links (bunker 2) en 1 vooraan rechts (bunker 1). De 'Cross of Sacrifice', midden achteraan, is gebouwd op een bunker (bunker 3) en draagt een gedenkplaat voor de '3rd Australian Division'. Achter dit kruis en de 'Stone of Remembrance' staat over de breedte van de begraafplaats het 'Tyne Cot Memorial'. Beschrijving Relict 'Tyne Cot Cemetery' is ontworpen door Sir Herbert Baker, met medewerking van J.R. Truelove. Het grondplan is rechthoekig met apsis in het O. Het heeft een oppervlakte van 34941 m². De aanleg gebeurde in verschillende niveaus; het terrein helt licht af. De begraafplaats is afgesloten door een muur van zwarte silexkeien ('flintstones'), afgedekt met witte natuursteen. Het toegangsgebouw is een poortgebouw eveneens uit zwarte silexkeien, afgewerkt met witte natuursteen. Op de architraaf boven de rondboog 'Tyne Cot Cemetery'. Daarboven een tentdakje. In de 2 zijmuren, uitgewerkt in een halve cirkel, met centraal het toegangsgebouw, en afgedekt door een zadeldakje, zijn 2 landplaten aangebracht. In het toegangsgebouw bevindt zich de derde landplaat (Engelstalig), en ook de metalen CWGC-plaat en het registerkastje. Er zijn ook zitbanken in witte natuursteen, waardoor het ook als schuilgebouwtje fungeert. De aanleg gebeurde in 66 perken. De voorste helft van de begraafplaats, in het W (het 'Concentration Cemetery') is rechtlijnig en symmetrisch aangelegd in een rechthoek, de achterste helft van de begraafplaats in het O, in een halve cirkel-vorm, waaiervormig en in kruisgangen. -

The Third Battle of Ypres

CENTENARY OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR THE CENTENARY OF PASSCHENDAELE – THE THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES The National Commemoration of the Centenary of Passchendaele – The Third Battle of Ypres The Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Tyne Cot Cemetery 31 July 2017 THE NATIONAL COMMEMORATION OF THE CENTENARY OF PASSCHENDAELE – THE THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES The Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Tyne Cot Cemetery 31 July 2017 Front cover: Stretcher bearers struggle in the mud at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge, 1 August 1917 © IWM 1 One hundred years ago today, British troops began their attempt to break out of the Ypres Salient. To mark this centenary, we return to the battlefield to honour all those involved in the ensuing battle which was fought in some of the most wretched conditions of the First World War. The battlefield of the Third Battle of Ypres, or Passchendaele as it became known, was like no other. A desolate landscape of quagmires and mud, coupled with fierce fighting, concentrated in a small area of ground across which thousands passed; the experience of Passchendaele was seared into the memory of all who survived. It is deeply humbling to consider how these men, on both sides, withstood such deplorable conditions. Passchendaele is in many ways a tale of human endurance and perseverance, through camaraderie and comradeship, bravery, humour and bittersweet memories of home. Many who survived the destruction of the battle, as well as the bereaved, would return after the war, bound to the fields of Flanders, to visit their own hallowed corners of the landscape, from beloved sanctuaries behind the front lines to the graves of fallen comrades and loved ones. -

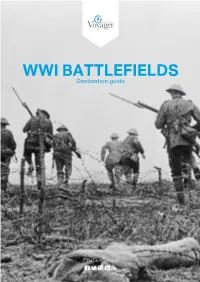

WWI BATTLEFIELDS Destination Guide

WWI BATTLEFIELDS Destination guide #BeThatTeacher 01273 827327 | voyagerschooltravel.com 1 Contents 3 Intro 4-7 History 7 Recreation 2 01273 827327 | voyagerschooltravel.com An introduction to the WWI Battlefields Intro In terms of battles of the First World War, or even of all time, the Somme and Ypres and regarded as amongst 2 of the most important and also most bloody. In the 21st century it is almost impossible to imagine the scale of the slaughter, with millions of lives lost in these 2 battles alone. The attritional nature of this type of warfare is quickly realised on a school tour, once a visit to a cemetery is followed by “it is almost another, or you read the names of the 72,000 men with no known grave on the sides of the Thiepval Memorial. impossible to The significance of these battles will be further understood imagine the scale of with visits to the battle sites themselves. Passchendaele is particularly moving, In Flanders Field Museum offers a huge the slaughter” volume of detail and attending the Last Post at the Menin Gate will give students a real sense of why remembrance is so important. All visits are covered by our externally verified Safety Management System and are pre-paid when applicable. Prices and opening times are accurate as of May 2018 and are subject to change and availability. Booking fees may apply to services provided by Voyager School Travel when paid on site. For the most accurate prices bespoke to your group size and travel date, please contact a Voyager School Travel tour coordinator at [email protected] 01273 827327 | voyagerschooltravel.com 3 The Menin Gate Memorial and Last Post as an “Every Man’s Club” for soldiers seeking an alternative to the “debauched” recreational life Ypres was the location of 5 major battles of the First of the town, Talbot House provided tea, cake and World War and the town was completely destroyed comfort for the Tommy for three years. -

Tyne-Cot Cemetery and Memorial Bei Passendale/Belgien (Tynecotstraat, Zonnebeke) - Der Größte Britische Soldatenfriedhof in Der Welt

Tyne-Cot Cemetery and Memorial bei Passendale/Belgien (Tynecotstraat, Zonnebeke) - der größte britische Soldatenfriedhof in der Welt Passendale ist ein Ort in Westflandern, zwischen Ypern und Roulers gelegen. “Tyne-Cot” (Kurzform für “Tyne- Cottage”) wurde von britischen Soldaten im Ersten Weltkrieg ein Blockhaus (Bunker) benannt, das westlich der Straße Passendale - Broodseinde (heutige N 303) stand und von der 2. Australischen Division am 4. Oktober 1917 beim Vorgehen auf Passendahle eingenommen wurde. Vom 6. Oktober 1917 bis Ende März 1918 beerdigten beiderseits von “Tyne-Cot” Einheiten des Britischen Empire (50th Northumbrian, 33rd Divisions und zwei kanadische Einheiten) 343 Gefallene. Vom 13. April bis 28. September 1918 fiel “Tyne-Cot” wieder in deutsche Hände, wurde dann aber von der belgischen Armee zurückerobert. Heute ruhen in “Tyne-Cot” 11 977 Soldaten, die auf den Schlachtfeldern um Passendale und Langemark vom Oktober 1917 bis September 1918 fielen: 8 961 Vereinigtes Königreich (darunter Flieger, Seeleute der “Royal Naval Division”) 1 368 Australien 1 011 Kanada 520 Neuseeland 90 Südafrika 14 Neufundland 6 “Royal Guernsey Light Infantry” 2 “British West Indies Regiment” 1 Frankreich 4 Deutschland (unweit vom “Cross of Sacrifice” beigesetzt, zwei breitere Steinstelen). 70 % der dort Bestatteten blieben unbekannt (= 8 366 Gefallene). Das “Cross of Sacrifice” wurde genau an der Stelle errichtet, wo seinerzeit das Blockhaus “Tyne-Cot” stand. Der Friedhof ist zweigeteilt. Im Teil oberhalb des Opferkreuzes ruhen die Gefallenen der Schlacht um die Anhöhe, im unteren Bereich hat man Gefallene aus anderen Kampfge- bieten zugebettet. Besondere Ehrenmale wurden für 38 Engländer, 27 Kanadier, 15 Australier und 1 Neusee- länder errichtet, die wohl auf diesem Friedhof beerdigt wurden, deren Gräber aber unauffind- bar blieben. -

Battle of Passchendaele: Centenary Commemorations

Battle of Passchendaele: Centenary Commemorations Summary On 19 October 2017, the House of Lords is due to debate a motion moved by Lord Black of Brentwood (Conservative) on “the Centenary of the Battle of Passchendaele and of Her Majesty’s Government’s plans to commemorate it”. The Third Battle of Ypres, or the Battle of Passchendaele as it became known, encapsulated a series of engagements fought between 31 July and 6 November 1917. In the words of historians Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, no Great War campaign excites stronger emotions, and no better word better encapsulates the horror of combat on the Western Front than ‘Passchendaele’.1 This briefing provides a short summary of the key events of the battle, describes the scale of the engagement and the casualties resulting from it, then details commemoration events which took place during this summer to honour those who lost their lives. Third Battle of Ypres Situated in the West Flanders region of Northern Belgium, the town of Ypres was the principal town within a salient (or ‘bulge’) in the lines of British forces, and the site of two previous battles: First Ypres (October–November 1914) and Second Ypres (April–May 1915).2 The campaign which led to the third battle had begun in an attempt by British and allied forces to drive towards key ports on the northern coast of Belgium, from which German U-boats were terrorizing military and commercial shipping in the English Channel and beyond. It also followed a successful attack on the Messines Ridge on 7 June 1917, whereby the detonation of huge mines under German lines had led to the capture of key objectives and a significant strategic victory.3 The Battle of Passchendaele was not to prove as quick or decisive a success, however. -

Battlefields Trip 'Ypres' and 'The Somme'

Battlefields Trip ‘Ypres’ and ‘The Somme’ Name: _______________________________________________ 1 My Name is: My Link Teacher / Anglia guide My roommates are: Belgium France (Comment on the things that you see and (Comment on the things that you see and experience: Language, houses jobs etc) experience: Language, houses jobs etc) 2 Contents Page: N.B. Shadowed boxes i.e. Indicate an opportunity for you to enhance your experience of the trip, it isn’t schoolwork but please attempt the task so that you get the most from the visit. It’s nice to look back at a future time and reflect on your experiences. Itinerary (may be subject to change) (* = Activity page) 3 Glossary: During this visit you will encounter many words, some of which will be new to you, so to make sure that you get the most from your visit, some are listed below: Flanders = name given to the flat land across N. France and Belgium Enfilade = when soldiers are shot/ attacked at from the side (flank). Salient = a “bulge” which sticks out into enemy land Artillery = large cannons or “guns” Front line = where opposing armies meet No-mans land = space between opposing armies Passchendaele = A village name, also given to the third Battle of Ypres “Wipers” = a nickname given to Ypres by British soldiers Division = a military term approximately 10,000 fighting men i.e. 29th Division- all armies were organised into Divisions. WARNING!! Over 90 years after the war unexploded munitions are still ploughed up in a dangerous, unstable condition. All such items must be treated with extreme caution and avoided. -

Passchendaele Remembered

1917-2017 PASSCHENDAELE REMEMBERED CE AR NT W E T N A A E R R Y G THE JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1980 JUNE/JULY 2017 NUMBER 109 2 014-2018 www.westernfrontassociation.com With one of the UK’s most established and highly-regarded departments of War Studies, the University of Wolverhampton is recruiting for its part-time, campus based MA in the History of Britain and the First World War. With an emphasis on high-quality teaching in a friendly and supportive environment, the course is taught by an international team of critically-acclaimed historians, led by WFA Vice-President Professor Gary Sheffield and including WFA President Professor Peter Simkins; WFA Vice-President Professor John Bourne; Professor Stephen Badsey; Dr Spencer Jones; and Professor John Buckley. This is the strongest cluster of scholars specialising in the military history of the First World War to be found in any conventional UK university. The MA is broadly-based with study of the Western Front its core. Other theatres such as Gallipoli and Palestine are also covered, as is strategy, the War at Sea, the War in the Air and the Home Front. We also offer the following part-time MAs in: • Second World War Studies: Conflict, Societies, Holocaust (campus based) • Military History by distance learning (fully-online) For more information, please visit: www.wlv.ac.uk/pghistory Call +44 (0)1902 321 081 Email: [email protected] Postgraduate loans and loyalty discounts may also be available. If you would like to arrange an informal discussion about the MA in the History of Britain and the First World War, please email the Course Leader, Professor Gary Sheffield: [email protected] Do you collect WW1 Crested China? The Western Front Association (Durham Branch) 1917-2017 First World War Centenary Conference & Exhibition Saturday 14 October 2017 Cornerstones, Chester-le-Street Methodist Church, North Burns, Chester-le-Street DH3 3TF 09:30-16:30 (doors open 09:00) Tickets £25 (includes tea/coffee, buffet lunch) Tel No. -

BELGIUM Destination Guide

BELGIUM Destination guide #BeThatTeacher 01273 827327 | voyagerschooltravel.com 1 Contents 3 Intro 4 Quick facts 5-7 History 7-8 Recreation 2 01273 827327 | voyagerschooltravel.com An introduction to Belgium Intro For a country relatively small in area, a school tour of Belgium can pack in a remarkable amount of varied and exciting visits and excursions for any educational subject. Miraculously, considering the number of wars and conflicts that have occurred here, the main cities have retained their medieval charm and atmosphere. Granted, the Grand Place in Brussels was rebuilt in the 19th century but very sympathetically and it retains the grandeur “There is an that is also found in Antwerp, Gent and of course, Bruges. Combine this with Belgium’s importance in the modern excellent cross- European political landscape and there is an excellent cross- curriculum breadth curriculum breadth of subjects to engage students on tour. The majority of trips we send to Belgium are concerned of subjects to with study of the world wars, the country suffered greatly in these conflicts and visits to Ypres and key battlefield sites engage students” just over the border in France gives students a real and vivid understanding of the horrors experienced. All visits are covered by our externally verified Safety Management System and are pre-paid when applicable. Prices and opening times are accurate as of May 2018 and are subject to change and availability. Booking fees may apply to services provided by Voyager School Travel when paid on site. For the most -

New Zealand Remembrance Trail Colophon

New Zealand Remembrance Trail Colophon: Chief & managing editor: Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917 Texts: Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917, Freddy Declerck Photography: MMP1917, Tourist Information Centre Zonnebeke, Freddy Lattré, Westtoer, Tourism Office Messines, Henk Deleu and Freddy Declerck Maps: Passchendaele Research Centre Zonnebeke Design & prepress: Impressionant Print | Impression: Lowyck & Pluspoint Website: www.passchendaele.be © - Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917, Berten Pilstraat 5/A, BE-8980 Zonnebeke. All the information dates from December 2016. A BRIEF HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND IN WORLD WAR I IN FLANDERS On 25 April 1915, ANZAC troops land on During October 1917 four ANZAC Divisions On 12 October 1917 the New Zealand Of all the nations involved in World War I, the Turkish peninsula, Gallipoli. After eight are at the centre of the major thrust in the Division launches an attack through deep New Zealand made the most significant months of stalemate the military operation at Battle of Passchendaele. One of these, the mud, heavy rain and strong winds to take the sacrifice in terms of population: over Gallipoli fails but the legend of the ANZACs New Zealand Division, is to provide central village of Passchendaele. Concrete pillboxes, 40,000 soldiers were wounded and more as soldiers of great courage, loyalty, sacrifice flanking support by seizing ‘s Graventafel machine guns and deep belts of barbed wire than 18,000 killed. But it was not entirely and comradeship is born. The New Zealand Spur on 4 October. It is a formidable task protect the German positions. The result is meaningless. The First World War spurred a Division is created in Egypt and moves to requiring the men to advance up open 2,700 casualties, including 846 dead in less greater awareness among New Zealanders of the Western Front. -

William Clark Died 16Th August 1917 Aged 20

William Clark William Clark was born at Bolton, Westmorland on 29 May 1897 and was the only son of John and Alice Anne Clark (nee Waring). He served as a Private (service number 25757) with the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment. William died during the Third Battle of Ypres on 16th August 1917 aged 20 and is remembered with honour at the Tyne Cot Memorial, Belgium. The Tyne Cot Memorial is one of four memorials to the missing in Belgian Flanders which cover the area known as the Ypres Salient 1 William is also remembered on his grandparents’ grave stone in Bolton Churchyard. He had a younger sister Maggie who married Richard Fothergill in 1929. William’s grandparents were also Bolton people, William and Christiana Clark (nee Johnstone) 1832 – 1895 and 1839 – 1915 respectively. William’s grandfather was descended from a long line of corn millers at mills throughout north Westmorland. Extract from1st Battalion Border Regiment in Belgium – The Third Battle of Ypres (1917) “The battle they had endured was a challenging one for several reasons, but simply owing to the nature of the ground they crossed, as well as fighting a formidable well-trained enemy, ensured they had a difficult time advancing to their objectives and reaching a successful outcome. The ground by its very characteristic, swampy yet “touch and direction were admirably kept throughout and endurance displayed by all ranks was beyond all praise, as the “going” was in appalling state, and during the previous three days the Battalion held the firing line for forty-eight hours and carried out two reliefs under shell fire.” There was no escaping casualties even with the successful outcome.