SERGEI PROKOFIEV Symphonies Nos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levit Spielt Brahms Fr 7

LEVIT SPIELT BRAHMS FR 7. September 2018 2 3 programm programm FR 7. September 2018 Kölner Philharmonie / 20.00 Uhr Johannes Brahms 19.00 Uhr Einführung Konzert Nr. 1 d-Moll Wibke Gerking für Klavier und Orchester op. 15 I. Maestoso II. Adagio III. Rondo. Allegro non troppo ~ 45 Minuten pause Arnold Schönberg Pelleas und Melisande Sinfonische Dichtung op. 5 (nach dem Drama von Maurice Maeterlinck) [I.] Die Achtel ein wenig bewegt – Heftig – Lebhaft – [II.] Sehr rasch – Ein wenig bewegt – [III.] Langsam – Ein wenig bewegter – [IV.] Sehr langsam – Etwas bewegt – In gehender Bewegung – Breit ~ 43 Minuten Jukka-Pekka Saraste Igor Levit Klavier WDR Sinfonieorchester Jukka-Pekka Saraste Leitung sendetermin wdr 3 SA 15. September 2018 20.04 Uhr wdr 3 konzertplayer digitales programmheft Zum Nachhören finden Sie Unter wdr-sinfonieorchester.de dieses Konzert 30 Tage lang im steht Ihnen fünf Tage vor WDR 3 Konzertplayer: wdr3.de jedem Konzert das jeweilige Programmheft zur Verfügung. Titelbild: Igor Levit 4 5 die werke die werke Die Ereignisse freilich überschlugen sich in den 1850er Jahren: 1853 veröffentlichte Schumann den Artikel »Neue Bahnen«, in dem er Brahms eine große Zukunft als Komponist prophezeite: »Am Cla- vier sitzend, fing er an wunderbare Regionen zu enthüllen. Wir wurden in immer zauberischere Kreise hineingezogen. Dazu kam ein ganz geniales Spiel, das aus dem Clavier ein Orchester von wehklagenden und lautjubelnden Stimmen machte. Es waren So- naten, mehr verschleierte Symphonien«. Damit war dem jungen KONZERT NR. 1 D-MOLL Komponisten klar, dass von ihm Sinfonisches erwartet wurde. Ent- sprechend wollte Brahms seine ursprünglich für zwei Klaviere kon- FÜR KLAVIER UND zipierte d-Moll-Sonate umarbeiten. -

559700 Bk Hanson US

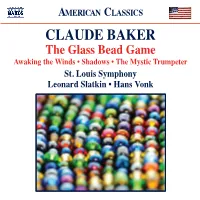

559642 bk Baker US_559642 bk Baker US 22/06/2012 21:07 Page 12 AMERICAN CLASSICS CLAUDE BAKER The Glass Bead Game Awaking the Winds • Shadows • The Mystic Trumpeter St. Louis Symphony Leonard Slatkin • Hans Vonk 8.559642 12 559642 bk Baker US_559642 bk Baker US 22/06/2012 21:07 Page 2 Claude Baker (b. 1948): The Glass Bead Game Hans Vonk Awaking the Winds • Shadows: Four-Dirge Nocturnes • The Mystic Trumpeter The distinguished Dutch conductor Hans Vonk assumed The Glass Bead Game (1982, rev. 1983) attained through a complete consumption and exhaustive the post of Music Director and Conductor of the St. Louis analysis only of the fruits of the past. Such a society, says Symphony in September 1996. A sought-after guest In 1943, the German novelist and philosopher Hermann Hesse, no matter how elite, how intellectual, how esoteric, conductor as well, he appeared with many of the world’s Hesse completed his last and (excepting Narcissus und must stagnate, wither and die. most prestigious orchestras and led performances at major Goldmund) greatest novel, Das Glasperlenspiel. Winner Claude Baker is saying much the same thing in his opera houses in Europe and North America, while also of the 1946 Nobel Prize for Literature, this book, the sum three-movement musical piece based on The Glass Bead remaining active in the musical life of his native Holland. and summit of Hesse’s thought and one of the most truly Game. His work, bearing the same title, is far more than a Vonk was Chief Conductor of the Netherlands Opera from relevant books of the era, was translated into English in programmatic reflection of Hesse’s novel; it is, remarkably, 1976 to 1985, during which time he was also Conductor of 1969 and brought out first with the title The Glass Bead like the novel, a philosophical mirror as well, in which the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic (1973-1979) and Game and subsequently as Magister Ludi (Master of the Baker utilizes Hesse’s methods and imagery to comment Associate Conductor of London’s Royal Philharmonic Game). -

Celebrating Slatkin Booklet FINAL

Marie-Hélène Bernard St. Louis Symphony Orchestra President & CEO Dear Leonard, When you made your conducting debut with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in 1968, who could have imagined that we’d gather on the same stage 50 years later to celebrate a remarkable partnership – one that redefined what an American orchestra could – and continues – to be. What you built with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra starting 50 years ago remains core to our mission. It’s the solid bedrock we’ve been building on for the past five decades: enriching lives through the power of music. Your years with the SLSO reshaped this orchestra, earning it the title of “America’s Orchestra.” You connected with our community – both here in St. Louis and on national and international stages. By taking this orchestra on the road, you introduced the SLSO and St. Louis to the world. You recorded with this orchestra more than any other SLSO music director, championing American composers and music of our time. Your passion for music education led to your founding of the St. Louis Symphony Youth Orchestra, which is the premiere experience for young musicians across our region. Next year, we will mark the Youth Orchestra’s golden anniversary and the thousands of lives it has impacted. We admire you for your remarkable spirit and talent and for your amazing vision and leadership. We are thrilled you have returned home to St. Louis and look forward to many years sharing special moments together. On behalf of the entire St. Louis Symphony Orchestra family, congratulations on the 50th anniversary of your SLSO debut. -

Naamloos 2.Pages

JOOST SMEETS CONDUCTOR JOOST SMEETS PAGINA: !1 Joost Smeets Lindepad 3 6017BW Thorn Nederland PHONE: +31 6 22387357 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.joostsmeets.com VIDEOS: https://vimeopro.com/culture2share/joost-smeets-conductor JOOST SMEETS PAGINA: !2 Biography 1st Prize winner of the Cordoba Conducting Competition Spain 2013, 1st Prize winner of the Black Sea International Conducting Competition Constanta Romania 2014, 1st Prize winner of the London Classical Soloïsts Conducting Competition United Kingdom 2016 2nd Prize winner of the Antal Dorati Int. Conducting Competition Budapest Hungary 2015, 3rd Prize winner (1st and 2nd Prize are not awarded) of the Ferruccio Busoni Int. Conducting Competition Empoli, Italy 2016 Principal Conductor and Artistic Director of the Chamber Philharmonic der Aa Groningen Holland (2010-2016) conducted with great acclaim in his career renowned orchestras in Opera and Symphonic programs including: - Boise Philharmonic Orchestra USA - Letvian National Symphony Orchestra Riga Letvia - North-Netherlands Symphony Orchestra Groningen Holland - Koszalin Philharmonic “Stanislaw Moniuszko” Poland - Wuhan Philharmonic Orchestra China - State Opera Rousse, Bulgaria - MAV Symphony Orchestra Budapest, Hungary - St. Petersburg State Symphony Orchestra Russia - Cordoba Symphony Orchestra Spain - Artez Conservatory Symphony Orchestra Zwolle Holland - Tomsk Philharmonic Orchestra Russia - Limburgs Symphony Orchestra Maastricht Holland - National Bulgarian Opera Bourgas Bulgaria - Württembergische Philharmonie -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 112, 1992-1993

One Hundred and Twelfth Season 1992-93 BOSTON (SYMPHONY ORCHE STRA SEIJI OZAWA, MUSIC DIRECTOR LASSALE THE ART OF SEIKO Bracelets, cases, and casebacks finished in 22 karat gold. EB. HORN Jewelers Since 1839 429 WASHINGTON ST. BOSTON 02108 617-542-3902 • OPEN MON. AND THURS. TIL 7 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director One Hundred and Twelfth Season, 1992-93 &*=^>^ Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, Vice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Nina L. Doggett R. Willis Leith, Jr. Peter A. Brooke Dean Freed Mrs. August R. Meyer James F. Cleary AvramJ. Goldberg Molly Beals Millman John F. Cogan, Jr. Thelma E. Goldberg Mrs. Robert B. Newman Julian Cohen Julian T. Houston Peter C. Read William F. Connell Mrs. BelaT. Kalman Richard A. Smith William M. Crozier, Jr. Allen Z. Kluchman Ray Stata Deborah B. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps Irving W. Rabb Philip K. Allen Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. George R. Rowland Allen G. Barry Mrs. John L. Grandin Mrs. George Lee Sargent Leo L. Beranek Mrs. George I. Kaplan Sidney Stoneman Mrs. John M. Bradley Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey AbramT. Collier Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John L. Thorndike Nelson J. Darling, Jr. Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Michael G. McDonough, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Administration Kenneth Haas, Managing Director Daniel R. Gustin, Assistant Managing Director and Manager ofTanglewood Michael G. -

559700 Bk Hanson US

AMERICAN CLASSICS CLAUDE BAKER The Glass Bead Game Awaking the Winds • Shadows • The Mystic Trumpeter St. Louis Symphony Leonard Slatkin • Hans Vonk Claude Baker (b. 1948): The Glass Bead Game comes to an end, the note “B” begins to disperse it and In that spirit, Claude Baker bases his second movement Awaking the Winds • Shadows: Four-Dirge Nocturnes • The Mystic Trumpeter dominate the movement, and Baker introduces the “Music on a paduana (a slow, courtly dance like a pavane) from of Decline.” The loud, violent outbursts in the winds and Johann Schein’s landmark Banchetto Musicale of 1617, The Glass Bead Game (1982, rev. 1983) attained through a complete consumption and exhaustive percussion signal the end of the “Age of the Feuilleton.” one of the first thematically integrated instrumental works analysis only of the fruits of the past. Such a society, says written in Germany. But Baker does not simply quote the In 1943, the German novelist and philosopher Hermann Hesse, no matter how elite, how intellectual, how esoteric, “…Old age and twilight had set in... the ‘music of Schein work; rather, he alternates it with his own Hesse completed his last and (excepting Narcissus und must stagnate, wither and die. decline’ had sounded... it raged somewhat atonal music, thus making the seventeenth- Goldmund) greatest novel, Das Glasperlenspiel. Winner Claude Baker is saying much the same thing in his as untrammeled and amateurish overproduction century music seem like a dream, like yesterday’s sunlight of the 1946 Nobel Prize for Literature, this book, the sum three-movement musical piece based on The Glass Bead in all the arts.” recalled from behind the veil of memory. -

Michael Faust

Masterclass Φλάουτου 7-9 Μαρτίου 2016, Iόνιος Ακαδημία Michael Faust (Robert Schumann Hochschule, Ντίσελντορφ Συμφωνική Ορχήστρα WDR, Κολωνίας) Επισκέπτης καθηγητής στο πλαίσιο του προγράμματος Erasmus+ Στο σεμινάριο θα συμμετέχουν ενεργά φοιτητές Kατεύθυνσης Eκτέλεσης Φλάουτου του Τ.Μ.Σ. Η παρακολούθηση του σεμιναρίου είναι ανοιχτή για ενδιαφερόμενους ακροατές. Οι ενδιαφερόμενοι μπορούν να ενημερώνονται για τις ακριβείς ώρες διεξαγωγής του σεμιναρίου από την υπεύθυνη διδάσκουσα του Τ.Μ.Σ. , κυρία Ρία Γεωργιάδου ([email protected]). Michael Faust's concert career began in his native Cologne, Germany, in 1975 where he was a student of Cäcilie Lamerichs. Later he studied in Hamburg with Karlheinz Zöller, principal flute of the Berlin Philharmonic, and with Aurèle Nicolet in Basel, Switzerland. Since then Michael has won prizes in prestigious music competitions in Rome, Prague and Bonn. As a 1986 Pro Musicis award winner in New York, he has accorded début concerts in such music centers as Boston, Washington, New York, Paris, Tokyo, and Osaka. Highlights of his solo-career include performances with the WDR-Symphony Orchestra, the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, and the Hilversum Symphony Orchestra, where he performed Gunther Schuller's flute concerto, with the Gürzenich-Orchestra Köln under Markus Stenz, the NDR-Symphony Orchestra as well as with the Moscow Radio-Symphony and the Spokane Symphony orchestras. He has also played as a soloist in halls like the Concertgebow Amsterdam, Berlin Philharmonic, Keio Hall in Tokyo, the Cologne Philharmonic and many others. In 2003 the renowned composer Mauricio Kagel wrote his only instrumental concerto for Michael Faust, who played his ‘Das Konzert’ in Duisburg, Düsseldorf and Hamburg among other cities. -

SYMPHONY #1, “A S (1903-9) Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

presents SYMPHONY #1, “A SEA SYMPHONY” (1903-9) Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) Performed by the UNIVERSITY SYMPHONY & COMBINED CHORUS Peter Erös, conductor 7:30 PM March 14, 2008 Meany Theater PROGRAM A Song for All Seas, All Ships On the Beach at night, Alone The Waves The Explorers A SEA SYMPHONY is a remarkably evocative piece of music by Ralph Vaughan Williams for a large choir, soprano and baritone soloists and orchestra. The text is from Walt Whitman’s collection “Leaves of Grass.” This is perfect for Vaughan Williams, encompassing everything from descrip– tions of ships at sea, daring explorers and innovators, introspection on the meaning of progress, the Second Coming, and a transcendent final voyage to the afterlife. Bertrand Russell introduced Vaughan Williams to the poet’s work while they were both undergraduates at Cambridge. The piece is a true choral symphony, where the choir leads the themes and drives the action, rather than merely intoning the words and pro– viding a bit of vocal color; it is more like an oratorio than a symphony. It is Vaughan Williams’ first symphonic work, and such was his lack of confidence in the area that he returned to study under Ravel in Paris for three months before he felt able to complete it. It was premiered in 1910 at the Leeds Festival. There are four movements: “A Song for all Seas, all Ships,” “On the Beach at night, Alone,” “The Waves,” and “The Explorers.” The first is an introduction, dealing with the sea, sailing ships and steamers, sailors and flags. -

4532.Pdf (166.8Kb)

PROGRAM PART ONE PART TWO Jonathan Pasternack, conductor Peter Erös, conductor Overture to LA FORZA DEL DESTINO ..... GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813-1901) from DIE WALKÜRE ..............................RICHARD WAGNER (1813-1883) Aria: “LEB’ WOHL” David Borning, baritone from LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN ... JACQUES OFFENBACH (1819-1880) Aria: “LES OISEAUX DANS LA CHARMILLE” Cecile Farmer, soprano from THE BARTERED BRIDE ............... BEDRICH SMETANA (1824-1884) Aria: “NOW, NOW MY DEAR” (VASHEK’S STUTTERING SONG) URELY YOU MUST BE THE BRIDEGROOM OF RU INA S ARIE from LA TRAVIATA ..................................................................... G. VERDI Duet: “S K ’ M ” Aria: “DE’ MIEI BOLLENTI SPIRITI” Nataly Wickham, soprano / Thomas Harper, tenor Duet: “UN DÌ FELICE” Aria: “AH FORS’ È LUI…SEMPRE LIBERA” from DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE ................................................. W. A. MOZART Tess Altiveros, soprano / David Margulis, tenor Aria: “EIN MÄDCHEN ODER WEIBCHEN” Duet: “PAPAGENA, PAPAGENO” from DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE ..................... WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Faina Morozov, soprano / Drew Dresdner, baritone Aria: “ACH, ICH FÜHL’S” (1756-1791) Arian Ashworth, soprano from AÏDA .................................................................................. G. VERDI Duet: “CIEL! MIO PADRE” from CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA ........... PIETRO MASCAGNI (1863-1945) Rebecca Paul, soprano / David Borning, baritone Aria: “VOI LO SAPETE” Brittany Hines-Hill, soprano from DER ROSENKAVALIER ................ RICHARD STRAUSS (1864-1949) Trio: “MARIE THERES! HAB’ -

The Pin-Up Boy of the Symphony: St. Louis and the Rise of Leonard

The Pin-Up Boy of the Symphony St. Louis and the Rise of Leonard Bernstein BY KENNETH H. WINN 34 | The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2018/2019 In May 1944 25-year-old publicized story from a New Leonard Bernstein, riding a York high school newspaper, had tidal wave of national publicity, bobbysoxers sighing over him as was invited to serve as a guest the “pin-up boy of the symphony.” conductor of the St. Louis They, however, advised him to get The Pin-Up Boy 3 Symphony Orchestra for its a crew cut. 1944–1945 season. The orchestra For some of Bernstein’s of the Symphony and Bernstein later revealed that elders, it was too much, too they had also struck a deal with fast. Many music critics were St. Louis and the RCA’s Victor Records to make his skeptical, put off by the torrent first classical record, a symphony of praise. “Glamourpuss,” they Rise of Leonard Bernstein of his own composition, entitled called him, the “Wunderkind Jeremiah. Little more than a year of the Western World.”4 They BY KENNETH H. WINN earlier, the New York Philharmonic suspected Bernstein’s performance music director Artur Rodziński Jeremiah was the first of Leonard Bernstein’s was simply a flash-in-the-pan. had hired Bernstein on his 24th symphonies recorded by the St. Louis Symphony The young conductor was riding birthday as an assistant conductor, Orchestra in the spring of 1944. (Image: Washing- a wave of luck rather than a wave a position of honor, but one known ton University Libraries, Gaylord Music Library) of talent. -

Missa Solemnis

2017 2018 SEASON David Robertson, conductor Saturday, November 18, 2017 at 8:00PM Joélle Harvey, soprano Sunday, November 19, 2017 at 3:00PM Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano Stuart Skelton, tenor Shenyang, bass-baritone St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director BEETHOVEN Mass in D major, op. 123, “Missa solemnis” (1823) (1770–1827) Kyrie Gloria Credo Sanctus Agnus Dei David Robertson, conductor Joélle Harvey, soprano Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano Stuart Skelton, tenor Shenyang, bass-baritone St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director David Halen, violin (Sanctus) This program is performed without intermission. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The 2017/2018 Classical Series is presented by World Wide Technology, The Steward Family Foundation, and Centene Charitable Foundation. These concerts are presented by the Thomas A. Kooyumjian Family Foundation. The concert of Saturday, November 18 is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Steve and Laura Savis. The concert of Sunday, November 19 is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs.* Robert H. Duesenberg. David Robertson is the Beofor Music Director and Conductor. Amy Kaiser is the AT&T Foundation Chair. Joélle Harvey is the Linda and Paul Lee Guest Artist. Kelley O’Connor is the Helen E. Nash, M.D. Guest Artist. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Richard E. Ashburner, Jr. Endowed Fund. *Deceased 23 BEETHOVEN’S MASS “FROM THE HEART” BY CHRISTOPHER H. GIBBS LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Born December 16, 1770, Bonn Died March 26, 1827, Vienna TIMELINKS Mass in D major, op. -

Recording Master List.Xls

UPDATED 11/20/2019 ENSEMBLE CONDUCTOR YEAR Bartok - Concerto for Orchestra Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop 2009 Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1978L BBC National Orchestra of Wales Tadaaki Otaka 2005L Berlin Philharmonic Herbert von Karajan 1965 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Ferenc Fricsay 1957 Boston Symphony Orchestra Erich Leinsdorf 1962 Boston Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1973 Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa 1995 Boston Symphony Orchestra Serge Koussevitzky 1944 Brussels Belgian Radio & TV Philharmonic OrchestraAlexander Rahbari 1990 Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer 1996 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Fritz Reiner 1955 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1981 Chicago Symphony Orchestra James Levine 1991 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Pierre Boulez 1993 Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Paavo Jarvi 2005 City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Simon Rattle 1994L Cleveland Orchestra Christoph von Dohnányi 1988 Cleveland Orchestra George Szell 1965 Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Antal Dorati 1983 Detroit Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1983 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Tibor Ferenc 1992 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Zoltan Kocsis 2004 London Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1962 London Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1965 London Symphony Orchestra Gustavo Dudamel 2007 Los Angeles Philharmonic Andre Previn 1988 Los Angeles Philharmonic Esa-Pekka Salonen 1996 Montreal Symphony Orchestra Charles Dutoit 1987 New York Philharmonic Leonard Bernstein 1959 New York Philharmonic Pierre