The Left and the Algerian Catastrophe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leftist Case for War in Iraq •fi William Shawcross, Allies

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 27, Issue 6 2003 Article 6 Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard∗ ∗ Copyright c 2003 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard Abstract Shawcross is superbly equipped to assess the impact of rogue States and terrorist organizations on global security. He is also well placed to comment on the risks of preemptive invasion for existing alliances and the future prospects for the international rule of law. An analysis of the ways in which the international community has “confronted evil,” Shawcross’ brief polemic argues that U.S. President George Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair were right to go to war without UN clearance, and that the hypocrisy of Jacques Chirac was largely responsible for the collapse of international consensus over the war. His curious identification with Bush and his neoconservative allies as the most qualified to implement this humanitarian agenda, however, fails to recognize essential differences between the leftist case for war and the hard-line justification for regime change in Iraq. BOOK REVIEW VENGEANCE AND EMPIRE: THE LEFTIST CASE FOR WAR IN IRAQ WILLIAM SHAWCROSS, ALLIES: THE U.S., BRITAIN, EUROPE, AND THE WAR IN IRAQ* Hal Blanchard** INTRODUCTION In early 2002, as the war in Afghanistan came to an end and a new interim government took power in Kabul,1 Vice President Richard Cheney was discussing with President George W. -

Download Document

ALGERIA: ADVERSARIES IN SEARCH OF UNCERTAIN COMPROMISES Rémy Leveau September 1992 © Institute for Security Studies of WEU 1996. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the Institute for Security Studies of WEU. ISSN 1017-7566 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction The context of coup d'état The forces involved in the crisis Questions and scenarios Postscript PREFACE Earlier this year the Institute asked Professor Rémy Leveau to prepare a study on `Algeria: adversaries in search of uncertain compromises.' This was discussed at a meeting of specialists on North African politics held in the Institute. In view of the continuing importance of developments in Algeria the Institute asked Professor Leveau to prepare this revised version of his paper for wider circulation. We are very grateful to Professor Leveau for having prepared this stimulating and enlightening analysis of developments which are also of importance to Algeria's European neighbours. We are also grateful to those who took part in the discussion of earlier drafts of this paper. John Roper Paris, September 1992 - v - Algeria: adversaries in search of uncertain compromises Rémy Leveau INTRODUCTION The perception of Islamic movements has been marked in Europe since 1979 by images of the Iranian revolution: hostages in the American Embassy, support for international terrorism, incidents at the mosque in Mecca and the Salman Rushdie affair. The dominant rhetoric of the FIS (Islamic Salvation Front) in Algeria, which has since 1989 presented a similar image of rejection of internal state order and of the international system, strengthens the feeling of an identity of aims and of a bloc of hostile attitudes. -

Co-Opting Identity: the Manipulation of Berberism, the Frustration of Democratisation, and the Generation of Violence in Algeria Hugh Roberts DESTIN, LSE

1 crisis states programme development research centre www Working Paper no.7 CO-OPTING IDENTITY: THE MANIPULATION OF BERBERISM, THE FRUSTRATION OF DEMOCRATISATION AND THE GENERATION OF VIOLENCE IN LGERIA A Hugh Roberts Development Research Centre LSE December 2001 Copyright © Hugh Roberts, 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this Working Paper should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Programme Working papers series no.1 English version: Spanish version: ISSN 1740-5807 (print) ISSN 1740-5823 (print) ISSN 1740-5815 (on-line) ISSN 1740-5831 (on-line) 1 Crisis States Programme Co-opting Identity: The manipulation of Berberism, the frustration of democratisation, and the generation of violence in Algeria Hugh Roberts DESTIN, LSE Acknowledgements This working paper is a revised and extended version of a paper originally entitled ‘Much Ado about Identity: the political manipulation of Berberism and the crisis of the Algerian state, 1980-1992’ presented to a seminar on Cultural Identity and Politics organized by the Department of Political Science and the Institute for International Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, in April 1996. Subsequent versions of the paper were presented to a conference on North Africa at Binghamton University (SUNY), Binghamton, NY, under the title 'Berber politics and Berberist ideology in Algeria', in April 1998 and to a staff seminar of the Government Department at the London School of Economics, under the title ‘Co-opting identity: the political manipulation of Berberism and the frustration of democratisation in Algeria’, in February 2000. -

Is God Great?

IS GOD GREAT? CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS AND THE NEW ATHEISM DEBATE Master’s Thesis in North American Studies Leiden University By Tayra Algera S1272667 March 14, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Second reader: Ms. N.A. Bloemendal MA 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1 – The New Atheism Debate and the Four Horsemen .............................................. 17 Chapter 2 – Christopher Hitchens ............................................................................................ 27 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................. 433 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................... 455 2 3 Introduction “God did not make us, we made God” Christopher Hitchens (2007) "What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence" Christopher Hitchens (2003) “Religion is violent, irrational, intolerant, allied to racism and tribalism and bigotry, invested in ignorance and hostile to free inquiry, contemptuous of women and coercive toward children." Christopher Hitchens (2007) These bold statements describe the late Christopher Hitchens’s views on religion in fewer than 50 words. He was a man of many words, most aimed at denouncing the role of religion in current-day societies. Religion is a concept that is hard -

Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State

Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State By Neil Grant Landers A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Debarati Sanyal, Co-Chair Professor Soraya Tlatli, Co-Chair Professor Karl Britto Professor Stefania Pandolfo Fall 2013 1 Abstract of the Dissertation Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State by Neil Grant Landers Doctor of Philosophy in French Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Debarati Sanyal, Co-Chair Professor Soraya Tlatli, Co-Chair Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State addresses the way the Algerian civil war has been portrayed in 1990s novelistic literature. In the words of one literary critic, "The Algerian war has been, in a sense, one big murder mystery."1 This may be true, but literary accounts portray the "mystery" of the civil war—and propose to solve it—in sharply divergent ways. The primary aim of this study is to examine how three of the most celebrated 1990s novels depict—organize, analyze, interpret, and "solve"—the civil war. I analyze and interpret these novels—by Assia Djebar, Yasmina Khadra, and Boualem Sansal—through a deep contextualization, both in terms of Algerian history and in the novels' contemporary setting. This is particularly important in this case, since the civil war is so contested, and is poorly understood. Using the novels' thematic content as a cue for deeper understanding, I engage through them and with them a number of elements crucial to understanding the civil war: Algeria's troubled nationalist legacy; its stagnant one-party regime; a fear, distrust, and poor understanding of the Islamist movement and the insurgency that erupted in 1992; and the unending, horrifically bloody violence that piled on throughout the 1990s. -

1 Copyright by Camille Alexandra Bossut 2016

Copyright by Camille Alexandra Bossut 2016 1 The Thesis committee for Camille Alexandra Bossut Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Arabization in Algeria: Language Ideology in Elite Discourse, 1962- 1991 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: ______________________________________ Benjamin Claude Brower ______________________________________ Mahmoud Al-Batal 2 Arabization in Algeria: Language Ideology in Elite Discourse, 1962-1991 by Camille Alexandra Bossut, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2016 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr. Benjamin Claude Brower and Dr. Mahmoud Al-Batal, for their time and willingness to guide me through this project. Dr. Brower’s continued feedback and inspiring discussions have taught me more about Algeria than I ever expected to learn in one year. Dr. Al-Batal has been an inspiration to me throughout my two years as a graduate student. I credit much of my linguistic development to his tireless encouragement and feedback. To Dr. Kristen Brustad, I extend my deepest gratitude for not only teaching me Arabic, but also teaching me how to think about language. Our many discussions on language ideology stoked my curiosity for exploring the topic of Arabization in more detail. Thank you for showing me how debates over language are rarely ever about language itself. I would also like to thank the Department of Middle Eastern Studies, the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, and the Arabic Flagship Program for their continued commitment to providing a high-quality, supportive, and enjoyable environment in which to learn Arabic. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

Islamist Vote’’

Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. DOI 10.1007/s41111-016-0018-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE From Peak to Trough: Decline of the Algerian ‘‘Islamist Vote’’ Chuchu Zhang1,2 Received: 14 October 2015 / Accepted: 13 March 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract What are the factors that facilitate or hinder Islamic political parties’ performance in elections in the Middle East and North Africa? Why did Algerian Islamists as an electoral force declined steadily over the past two decades? Why didn’t Algerian electoral Islamists present the same mobilization capacity as their counterparts in neighboring countries did in early 2010s following the Arab Spring? In analyzing the evolution of three related variables: incumbents’ power structure and political openness; electoral Islamists’ inclusiveness and unity; and the framing process of Islamic political parties to build a legitimacy, the article tries to address the questions and contribute to the theoretical framework of the political process model by applying it to a case that is typical in MENA. Keywords Islamic political parties Á Mobilization capacity Á Algeria 1 Introduction Understanding Islamic political parties1 becomes an urgent concern following the Arab Spring, as the anti-authoritarian protests resulted in the rise of Islamists at the ballot box in 2011 in lots of countries in MENA (Middle East and North Africa) including Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco. A wider audience are now interested in 1 Islamic political parties here refer to the organizations that are ideologically based on Islamic texts and frameworks, and seek legal political participation through elections. Apolitical Islamic cultural associations and armed Islamist organizations which refuse to engage in elections are beyond the scope of this article. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Ethnicity in Algeria

Algeria Ethnicity in Algeria Group selection The Arabs (72%) and Berbers (or: Amazigh) (28%) are politically relevant ethnic groups in Algeria. Power relations Algeria gained independence from France in 1962 following a war that lasted for nearly a decade. The anti-colonial nationalism which fueled the struggle for Algerian independence had developed in tan- dem with the rise of Arab nationalism. Thus, similar to other newly independent North African states, Algerian identity was “generally defined by nationalist orthodoxy as Arabo-Muslim” (37). The Na- 37 [International Crisis Group, 2003] tional Liberation Front (FLN), the country’s primary political party, was established in 1954 as part of the struggle for independence and has since largely dominated politics. The FLN has legitimized their power by propagating the vision of a unified Arab-Muslim nation. In 1962 Ait Ahmed founded the Socialist Forces Front (Front des forces socialistes, FFS) in an effort to challenge the hegemony of the FLN in the country’s one party system. Although Ait Ahmed was Berber, his primary goal was a power sharing structure for the new state, not to advance his ethnic group’s rights. Many members of the 1962 constituent assembly (one-party, FLN) were Berber and over half opposed Ait Ahmed and the FFS, highlighting that politics were not primarily defined by ethnic divides. Algeria does not have a ‘Berber party’ which appeals to Algeria’s Berbers per definition. However, it can be said that the Berber vision of the nation was excluded from post-independence nation- building, leading to a greater consciousness of Berber identity and resentment against the lack of its recognition in national politics. -

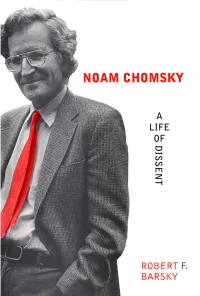

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky Addressing a Crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky addressing a crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989. Noam Chomsky A Life of Dissent Robert F. Barsky ECW PRESS Copyright © ECW PRESS, 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process—electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW PRESS. CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Barsky, Robert F. (Robert Franklin), 1961- Noam Chomsky: a life of dissent Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55022-282-1 (bound) ISBN 1-55022-281-3 (pbk.) 1. Chomsky, Noam. 2. Linguists—United States—Biography. I. Title. P85.C47B371996 410'.92 C96-930295-9 This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and with the assistance of grants provided by the Ontario Arts Council and The Canada Council. Distributed in Canada by General Distribution Services, 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Ontario M3B 2T6. Distributed in the United States and internationally by The MIT Press. Photographs: Cover (1989), frontispiece (1989), and illustrations 18, 24, 25 (1989), © Elaine Briere; illustration 1 (1992), © Donna Coveney, is used by per- mission of Donna Coveney; illustrations 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20,21,22,23,26, © Necessary Illusions, are used by permission of Mark Achbar and Jeremy Allaire; illustrations 5, 8, 9, 10 (1995), © Robert F. -

New Middle Eastern Studies Publication Details, Including Guidelines for Submissions

New Middle Eastern Studies Publication details, including guidelines for submissions: http://www.brismes.ac.uk/nmes/ Immunity to the Arab Spring? Fear, Fatigue and Fragmentation in Algeria Author(s): Edward McAllister To cite this article: McAllister, Edward, ―Immunity to the Arab Spring? Fear, Fatigue and Fragmentation in Algeria‖, New Middle Eastern Studies, 3 (2013), <http://www.brismes.ac.uk/nmes/archives/1048>. To link to this article: http://www.brismes.ac.uk/nmes/archives/1048 Online Publication Date: 7 January 2013 Disclaimer and Copyright The NMES editors and the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies make every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information contained in the e-journal. However, the editors and the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness or suitability for any purpose of the content and disclaim all such representations and warranties whether express or implied to the maximum extent permitted by law. Any views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and not the views of the Editors or the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies. Copyright New Middle Eastern Studies, 2013. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from New Middle Eastern Studies, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed, in writing. Terms and conditions: This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.