An Introduction to Utah's Indian History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

THREE SACRED VALLEYS): an Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S

Paitu Nanasuagaindu Pahonupi (THREE SACRED VALLEYS): An Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S. Air Force Electronic Combat Test Capability Actions and Alternatives at the Utah Test and Training Range Item Type Report Authors Stoffle, Richard W.; Halmo, David; Olmsted, John Publisher Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan Download date 01/10/2021 12:00:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/271235 PAITU NANASUAGAINDU PAHONUPI(THREE SACRED VALLEYS): AN ASSESSMENT OF NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURAL RESOURCES POTENTIALLY AFFECTED BY PROPOSED U.S. AIR FORCE ELECTRONIC COMBAT TEST CAPABILITY ACTIONS AND ALTERNATIVES AT THE UTAH TEST AND TRAINING RANGE DRAFT INTERIM REPORT By Richard W. Stoffle David B. Halmo John E. Olmsted Institute for Social Research University of Michigan April 14, 1989 Submitted to: Science Applications International Corporation Las Vegas, Nevada TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Description of Study Area 2 Description of Project 2 Site Specific Assessment 3 Tactical Threat Area 3 Threat Sites and Array 4 Range Maintenance Facilities 4 Programmatic Assessment 5 Airspace and Flight Activities Effects 5 Gapfiller Radar Site 5 Future Programmatic Assessments 5 Commercial Power 5 Fiber -optic Communications Network 5 Project - Related Structures and Activities on DOD lands 5 CHAPTER TWO ETHNOHISTORY OF INVOLVED NATIVE AMERICAN GROUPS 7 Ethnic Groups and Territories 7 Overview 7 Gosiutes 9 Pahvants 12 Utes 13 Early Contact, Euroamerican Colonization, -

The SKULL VALLEY GOSHUTES and the NUCLEAR WASTE STORAGE CONTROVERSY TEACHER BACKGROUND

Timponogos - Ute Deep Creek Mountains - Goshute THE GOSHUTES the SKULL VALLEY GOSHUTES AND THE NUCLEAR WASTE STORAGE CONTROVERSY TEACHER BACKGROUND The Skull Valley Band of Goshute Reservation, located approximately forty-five miles southwest of Monument Valley - Navajo Salt Lake City, was established by executive order in 1912 and covers 17,248 acres. With limited land holdings in a sparse, secluded landscape, the Skull Valley Band has struggled to develop a viable economic base. In the 1990s, the nation’s executive council undertook efforts to locate a temporary nuclear waste storage site on the reservation. The history of this controversial issue highlights the OGoshutes’BJectiV Estruggle for sovereignty, economic independence, and environmental security. - The student will be able to comprehend how tribal sovereignty is complicated by disagreements over land use, economic development, and state vs. federal control. They will also understand the econom ic and ecological variables that have shaped the Skull Valley Band of Goshute’s attempted acquisition of a nuclear waste storage facility. Teacher Materials At a Glance: We Shall Remain: The Goshute Goshute Sovereignty and the Contested West Desert Student Materials (chapter 4, 18:37–22:05)TIME Frame - Versatile Debate: Should the Goshutes Build a Temporary Two block periods with homework Nuclear Waste Storage Site on the Skull Valley Three standard periods with homework Reservation? YES: Forrest Cuch NO: Margene Bullcreek Procedure Using information from At a Glance: from We Shall Remain: The Goshute Goshute Sovereignty and the Contested West Desert and clips , teach your students about the controversy over nuclear waste storage on the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Reservation. -

Petition for Declaratory Relief and in Alternative Informal Request for Commission Action

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) ) UINTAH BASIN ELECTRONIC ) TELECOMMUNICATIONS, LLC ) D/B/A STRATA NETWORKS ) ) To: The Commission PETITION FOR DECLARATORY RELIEF AND IN ALTERNATIVE INFORMAL REQUEST FOR COMMISSION ACTION NORTHWEST BAND OF SHOSHONE NATION SKULL VALLEY BAND OF GOSHUTE INDIANS Stephen Díaz Gavin RIMON, P.C. 1717 K Street, N.W., Suite 900 Washington, D.C. 20006 (202) 871-3772 [email protected] Their Counsel Dated: March 27, 2020 Summary Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (“NHPA”) provides that Native American tribes be afforded the opportunity to be consulted regarding the means by which adverse effects on historic property will be considered before the construction of the undertaking.1 In the context of antenna towers and communications facilities, the Commission has made clear that applicants and licensees are required to assess whether certain proposed facilities may significantly affect the environment, as defined in Section 1.1307 of the Rules, specifically including construction that might disturb Native American religious sites. In re Sprint Corporation (Consent Decree), 33 FCC Rcd 3440 (Enforcement Bur. 2018). See also In re Nationwide Agreement Regarding the Section 106 [NHPA] Review Process (Section 106 Agreement), 20 FCC Rcd 1073 (2004). The D.C. Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals has only recently reiterated that the Commission has a binding legal duty under the NHPA to consider the impact of radio tower constructions on sites of historical, cultural and religious importance to the Native American tribes. United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Okla. -

Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Wah Wah Valley Solar Energy Zone

Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Wah Wah Valley Solar Energy Zone Ethnography and Ethnographic Synthesis For Solar Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement and Solar Energy Study Areas in Portions of Arizona, California, Nevada, and Utah Participating Tribes Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, Ibapah, Utah Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, Cedar City, Utah By Richard W. Stoffle Kathleen A. Van Vlack Hannah Z. Johnson Phillip T. Dukes Stephanie C. De Sola Kristen L. Simmons Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology School of Anthropology University of Arizona October 2011 Solar PEIS Ethnographic Assessment Page 1 WAH WAH VALLEY The proposed Wah Wah Valley solar energy zone (SEZ) is located in the southwestern portion of Utah and is outlined in red below (Figure 1). The proposed Wah Wah Valley SEZ sits in Beaver County, approximately 50 miles northwest of Cedar City and 34 miles east of the Utah/Nevada state line. State-route 21 runs through the length of the northern portion of the SEZ and provides access to the area. Figure 1 Google Earth Image of Wah Wah Valley SEZ American Indian Study Area The greater Wah Wah Valley SEZ American Indian study area lies in the Utah Basin and Range province within the Wah Wah Valley. The larger SEZ American Indian study area extends beyond the boundaries of the proposed SEZ because the presence of cultural resources extends into the surrounding landscape. The Wah Wah Valley SEZ American Indian study area includes plant communities, geological features, water sources, and trail systems located in and around the SEZ boundary. -

California-Nevada Region

Research Guides for both historic and modern Native Communities relating to records held at the National Archives California Nevada Introduction Page Introduction Page Historic Native Communities Historic Native Communities Modern Native Communities Modern Native Communities Sample Document Beginning of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the U.S. Government and the Kahwea, San Luis Rey, and Cocomcahra Indians. Signed at the Village of Temecula, California, 1/5/1852. National Archives. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/55030733 National Archives Native Communities Research Guides. https://www.archives.gov/education/native-communities California Native Communities To perform a search of more general records of California’s Native People in the National Archives Online Catalog, use Advanced Search. Enter California in the search box and 75 in the Record Group box (Bureau of Indian Affairs). There are several great resources available for general information and material for kids about the Native People of California, such as the Native Languages and National Museum of the American Indian websites. Type California into the main search box for both. Related state agencies and universities may also hold records or information about these communities. Examples might include the California State Archives, the Online Archive of California, and the University of California Santa Barbara Native American Collections. Historic California Native Communities Federally Recognized Native Communities in California (2018) Sample Document Map of Selected Site for Indian Reservation in Mendocino County, California, 7/30/1856. National Archives: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/50926106 National Archives Native Communities Research Guides. https://www.archives.gov/education/native-communities Historic California Native Communities For a map of historic language areas in California, see Native Languages. -

Native American Records on Microfilm

Native American Indian midwestgenealogycenter.org Records on Microform Access Your History 12602 NATIVE AMERICAN RECORDS Roll listings may be found in American Indians: A Select Catalog of National Archives Microfilm Publications Apache Apache Film Drawer 57 Camp McDowell: 1905-1909, 1911-1912 M595 Roll 15 Apache and Mojave Film Drawer 57 Camp Verde: 1915-1927 M595 Roll 15 White Mountain Apache Film Drawer 59 Fort Apache: 1898-1927, 1929-1939 M595 Rolls 118-125 Kiowa, Comanche, Apache, Caddo, and Wichita and Affiliated Indians Film Drawer 60 1895-1913 M595 Rolls 211-213 Kiowa, Comanche, Apache, Caddo, and Apache Prisoners of War or Fort Sill Apache Film Drawer 60 1914-1930 M595 Rolls 214-218 Kiowa, Comanche, Apache, Fort Sill Apache, Wichita and Caddo, and Delaware Film Drawer 60 1931-1939 (with Birth and Death Rolls: 1924-1932) M595 Rolls 219-223 Pima, Apache, and Mohave-Apache of the Camp Verde, Fort McDowell, and Salt River Reservations Film Drawer 62 Phoenix: 1928-1933 (with Birth and Death Rolls: 1924-1932) M595 Rolls 344-345 Pima, Papago, Maricopa and Mojave-Apache of the Fort McDowell, Gila River, Maricopa or Ak Chin, and Salt River Reservations Film Drawer 62 1934-1939 (Supplemental Rolls only) M595 Rolls 358-361 Jicarilla Apache Film Drawer 62 1892, 1893-1895, 1897-1899 M595 Rolls 399-400 Apache, Mohave, and Yuma Film Drawer 63 San Carlos: 1887-1890, 1892-1902, 1904-1912, 1914-1939 M595 Rolls 461-470 Shivwits or Shebits and Kaibab, Ute and Jicarilla Apache Film Drawer 64 Southern Utah: 1897-1905; Southern Ute: 1885-1892 M595 -

Great Basin Region Revised 2020

Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History Repatriation Office Case Report Summaries Great Basin Region Revised 2020 Great Basin Bannock, 1992 INVENTORY AND ASSESSMENT OF NATIVE AMERICAN HUMAN Paiute, REMAINS FROM THE WESTERN GREAT BASIN, NEVADA Shoshone, SECTOR, IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Washoe This is the first of two reports that will document the human remains in the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) from the Great Basin region. This report focuses on the western half of the Great Basin, providing an inventory and assessment of the skeletal remains in the museum from the region circumscribed by the modern political boundaries of the state of Nevada. Documentation of the human remains from the western Great Basin was initiated in November 1991 in response to an earlier request from the Pyramid Lake Paiute of northwestern Nevada for the return of any historic Paiute skeletal remains and associated artifacts from their territory. In addition to the Pyramid Lake Paiute, other native peoples potentially affected by the findings of this report include other sub-groups of the Northern Paiute, the Shoshone, the Bannock, and the Southern Paiute. A total of 56 sets of remains in the Physical Anthropology division of the NMNH were identified as having come from the western half of the Great Basin, which is defined for purposes of this report as the state of Nevada. Forty of these skeletal lots were determined to date to the historic period, while 16 sets of remains are prehistoric in origin. In compliance with Public Law 101-185, these remains were evaluated in terms of their probable cultural affiliation. -

Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Escalante Valley Solar Energy Zone

Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Escalante Valley Solar Energy Zone Participating Tribes Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, Ibapah, Utah Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, Cedar City, Utah Ethnography and Ethnographic Synthesis For Solar Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement and Solar Energy Study Areas in Portions of Arizona, California, Nevada, and Utah By Richard W. Stoffle Kathleen A. Van Vlack Hannah Z. Johnson Phillip T. Dukes Stephanie C. De Sola Kristen L. Simmons Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology School of Anthropology University of Arizona October 2011 Solar PEIS Ethnographic Assessment Page 1 ESCALANTE VALLEY The proposed Escalante Valley solar energy zone (SEZ) is located in Iron County, Utah (Figure 1). It is approximately four miles south of Lund, Utah and ten miles east of Beryl, Utah. The SEZ is situated in the Escalante Valley, which is a large, southwest-northeast trending valley in the south-central portion of the Escalante Desert. Figure 1 Google Earth Image of the Escalante Valley SEZ Outlined in Red and SEZ American Indian Study Area The Escalante Valley SEZ American Indian study area extends beyond the boundaries of the SEZ because of the existence of cultural resources in the surrounding landscape. The Escalante Valley SEZ American Indian study area includes plant and animal communities, geological features, water sources, historic events and the trails that would have connected these features. Southern Paiute and Goshute representatives maintain that, in order to understand Numic connections to the SEZ, it must be placed in context with neighboring connected places including the Milford Flats South and Wah Wah Valley SEZs and their associated cultural resources found in the larger study areas. -

Reconciling Native Sovereignty and the Federal Trust Lincoln L

Maryland Law Review Volume 68 | Issue 2 Article 4 Skull Valley Crossroads: Reconciling Native Sovereignty and the Federal Trust Lincoln L. Davies Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln L. Davies, Skull Valley Crossroads: Reconciling Native Sovereignty and the Federal Trust, 68 Md. L. Rev. 290 (2009) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol68/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\server05\productn\M\MLR\68-2\MLR202.txt unknown Seq: 1 26-FEB-09 11:15 Articles SKULL VALLEY CROSSROADS: RECONCILING NATIVE SOVEREIGNTY AND THE FEDERAL TRUST LINCOLN L. DAVIES* ABSTRACT It has been long recognized that a deep tension pervades federal American Indian law. The foundational principles of the field—on the one hand, the notion that tribes keep their inherent right of sover- eignty and, on the other, that the federal government has a power and duty to protect them—clash on their face. Despite years of criti- cism of this conflict, the two principles continue to coexist, albeit un- comfortably. Using the example of the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians’ controversial proposal to store high-level nuclear waste on their land, this Article revisits the tension in these doctrines, weighs prior proposals attempting to reconcile them, and concludes that, ul- timately, sovereignty and the federal trust are not reconcilable. -

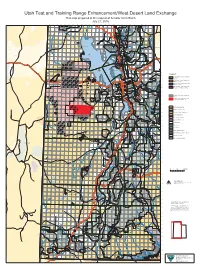

IB2017-043 Att3.Pdf

Utah Test and Training Range Enhancement/West Desert Land Exchange This map prepared at the request of Senator Orrin Hatch July 21, 2016 R 19W R 18W R 17W R 16W R 15W R 14W R 13W R 12W R 11W R 10W R 9W R 8W R 7W R 6W R 5W R 4W R 3W R 2W R 1W R 1E R 2E R 3E R 4E R 5E R 6E R 7E L B Lewiston o B ea g Wasatch-Cache l Caribou a u r n e National R i Richmond R C Forest v National Sawtooth e i v r r e e r e e 91 r Forest National k r C k ea S ree B o C e Forest it ittl F m L um k C S k u r Cyn J r tl h e e e e irc u r 89 e v v B r R i L n i R e Smithfield c s o C r R t g e r i a C o a lu e a n n B e 84 u r k B e t B N v e l Hyde Park i e e R o r r n r t a C R h g p e North Logan e o e s r L e C n D u t l L ver k Logan n Ri D Garland e o Loga ov e e r g C e a r ee r R n k R River Heights Tremonton e C i Mendon s v e e u L r l it B t Providence l e B Nibley e Millville Cache a Randolph r R i Honeyville Wellsville v H Hyrum y Bla ru cks m mith R Fo e rk s r k e e v i e r 89/91 R C Wasatch-Cache r a e Rich e s Corinne u National Forest B o r G r E Fk G S e Lit Be L iv Bear l ar River R Brigham City a Box Elder n r E a a ch Creek irch Creek e Bir B F k C Bear River B k ree Wyoming L C i ff G Migratory t ru SL B od Perry e o Bird Refuge a W 15 r ek re C f G L Willard f S u S G r L d o o Weber W k e e k r r C n o Pleasant View L o r F o e P e s v l t a n d Plain City C Farr West North Ogden d e o i i B r t M e a W Harrisville e r e k o r be p e r rk a b R Pin Fo v e e iv view R th s e 89 River es u E W n So r de n G g i SL k er n River O F b Ogde a -

Coyote Steals Fire

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2005 Coyote Steals Fire Northwest Band Shoshone Nation Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons Recommended Citation Northwestern Band of Shoshoni Nation of Utah (Washakie). (2005). Coyote steals fire: A Shoshone tale. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coyote Steals Fire A Shoshone Tale Retold and Illustrated by The Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation Utah State University Press Logan, UT 84322-7800 Copyright 2005 The Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coyote steals fire : a Shoshone tale / retold and illustrated by the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation. p. cm. ISBN 0-87421-618-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Shoshoni Indians--Folklore. 2. Coyote (Legendary character)--Legends. I. Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation. E99.S4C69 2005 398.24’5297725’089974574--dc22 2005021098 Coyote Steals Fire A Shoshone Tale Retold and Illustrated by Utah State The Northwestern Band University Press of the Shoshone Nation Logan, Utah Every winter, Grandmother came to the Moson Kahni valley to gather with her people. There were hot springs here, and fish, game, and plenty of shelter. It was the old ones’ time. Grandmother was a storyteller. “Grandmother, tell us how Itsappe —Old Coyote—stole fire!” “Oh, that’s a good story.