Essays in Swahili Geographical Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music of Ghana and Tanzania

MUSIC OF GHANA AND TANZANIA: A BRIEF COMPARISON AND DESCRIPTION OF VARIOUS AFRICAN MUSIC SCHOOLS Heather Bergseth A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERDecember OF 2011MUSIC Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2011 Heather Bergseth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor This thesis is based on my engagement and observations of various music schools in Ghana, West Africa, and Tanzania, East Africa. I spent the last three summers learning traditional dance- drumming in Ghana, West Africa. I focus primarily on two schools that I have significant recent experience with: the Dagbe Arts Centre in Kopeyia and the Dagara Music and Arts Center in Medie. While at Dagbe, I studied the music and dance of the Anlo-Ewe ethnic group, a people who live primarily in the Volta region of South-eastern Ghana, but who also inhabit neighboring countries as far as Togo and Benin. I took classes and lessons with the staff as well as with the director of Dagbe, Emmanuel Agbeli, a teacher and performer of Ewe dance-drumming. His father, Godwin Agbeli, founded the Dagbe Arts Centre in order to teach others, including foreigners, the musical styles, dances, and diverse artistic cultures of the Ewe people. The Dagara Music and Arts Center was founded by Bernard Woma, a master drummer and gyil (xylophone) player. The DMC or Dagara Music Center is situated in the town of Medie just outside of Accra. Mr. Woma hosts primarily international students at his compound, focusing on various musical styles, including his own culture, the Dagara, in addition music and dance of the Dagbamba, Ewe, and Ga ethnic groups. -

Kenya.Pdf 43

Table of Contents PROFILE ..............................................................................................................6 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Facts and Figures.......................................................................................................................................... 6 International Disputes: .............................................................................................................................. 11 Trafficking in Persons:............................................................................................................................... 11 Illicit Drugs: ................................................................................................................................................ 11 GEOGRAPHY.....................................................................................................12 Kenya’s Neighborhood............................................................................................................................... 12 Somalia ........................................................................................................................................................ 12 Ethiopia ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 Sudan.......................................................................................................................................................... -

Wildlife and Forest Biodiversity Conservation in Taita, Kenya Njogu, J.G

Community-based conservation in an entitlement perspective: wildlife and forest biodiversity conservation in Taita, Kenya Njogu, J.G. Citation Njogu, J. G. (2004). Community-based conservation in an entitlement perspective: wildlife and forest biodiversity conservation in Taita, Kenya. Leiden: African Studies Centre. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12921 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12921 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Community-based conservation in an entitlement perspective African Studies Centre Research Report 73 / 2004 Community-based conservation in an entitlement perspective Wildlife and forest biodiversity conservation in Taita, Kenya James Gichiah Njogu This PhD project was part of the research programme Resources, Environment and Development Research Associates (REDRA) of the Amsterdam Research Institute for Global Issues and Development Studies (AGIDS). It also formed part of Working Programme 1, Natural resource management: Knowledge transfer, social insecurity and cultural coping, of the Research School for Resource Studies for Development (CERES). The Netherlands Foundation for the Advancement of Tropical Research (WOTRO) jointly with the Amsterdam Research Institute for Global Issues and Development Studies (AGIDS) of the University of Amsterdam funded this research. The School of Environmental Studies of Moi University (Eldoret, Kenya) provided institutional support. Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden Tel: + 31 - 71 - 527 33 72 Fax: + 31 - 71 - 527 33 44 E-mail: [email protected] Website:http://asc.leidenuniv.nl Printed by: PrintPartners Ipskamp B.V., Enschede ISBN 90.5448.057.2 © African Studies Centre, Leiden, 2004 Contents List of maps viii List of figures viii List of boxes viii List of tables ix List of plates x List of abbreviations x Acknowledgements xii PART 1: THE CONTEXT 1 1. -

Meteorologia

MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 15/SDOP, DE 25 DE JULHO DE 2006. Aprova a reedição da Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, inciso IV, da Portaria DECEA n°136-T/DGCEA, de 28 de novembro de 2005, RESOLVE: Art. 1o Aprovar a reedição da ICA 105-1 “Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas”, que com esta baixa. Art. 2o Esta Instrução entra em vigor em 1º de setembro de 2006. Art. 3o Revoga-se a Portaria DECEA nº 131/SDOP, de 1º de julho de 2003, publicada no Boletim Interno do DECEA nº 124, de 08 de julho de 2003. (a) Brig Ar RICARDO DA SILVA SERVAN Chefe do Subdepartamento de Operações do DECEA (Publicada no BCA nº 146, de 07 de agosto de 2006) MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 33 /SDOP, DE 13 DE SETEMBRO DE 2007. Aprova a edição da emenda à Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, alínea g, da Portaria DECEA n°34-T/DGCEA, de 15 de março de 2007, RESOLVE: Art. -

Service, Slavery ('Utumwa') and Swahili Social Reality

AAP 37 (1994}. 87-107 SERVICE, SLAVERY ('UTUMWA') AND SWAHILI SOCIAL REALITY CAROL M. EASTMAN Introduction A basic dichotomy between what is civilized (uungwana) and what is barbarian (ushenzi or 'foreign, strange') has existed for centuries on the East African Coast. The concept of utumwa 'slavery, service' may be seen to mediate the opposition between the civilized and the uncivilized over time In this paper, I invoke a sociolinguistic approach to complement the historical record in order to examine the use of the word utumwa itself as it has changed to reveal distinct class and gender connotations especially in northem Swahili communities. To explore utumwa is difficult. There is no consensus with regard to what the word and its derivatives mean that applies consistently, yet it is clear that there has been a meaning shift since the nineteenth century. This paper examines the construction and transformation of a non-Westem-molded form of service in Africa. Oral traditions and terminological variation will be brought to bear on an analysis of utumwa 'slavery, service' as an important concept of social change in East Africa and, in particular, on the northern Kenya coast What this term, its derivatives, and other terms associated with it have come to mean to Swahili speakers and culture bearers will be seen to mirror aspects of the history of Swahili-speaking people fi-om the 1Oth-11th century to the present Utumwa functioned in contrast to notions of civilization (uungwana) and, later, Arabness (uarabu or ustaarabu). The construction -

Esoto: Where Girls and Warriors Meet the Changing Space and Perceptions of Esoto Over Generations of the Maasai Women of Engare Sero Lisa Wilmore SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2010 Esoto: Where Girls and Warriors Meet The Changing Space and Perceptions of Esoto Over Generations of the Maasai Women of Engare Sero Lisa Wilmore SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, Dance Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Wilmore, Lisa, "Esoto: Where Girls and Warriors Meet The hC anging Space and Perceptions of Esoto Over Generations of the Maasai Women of Engare Sero" (2010). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 900. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/900 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Esoto: where girls and warriors meet The changing space and perceptions of esoto over generations of the Maasai women of Engare Sero by Lisa Wilmore SIT Tanzania: Political Ecology and Wildlife Conservation Fall 2010 Acknowledgements I must first express my thanks to the Engare Sero community who welcomed Team Natron into a place that we have all come to love after our three-week stay. Your generosity and friendship made our experience memorable. Thank you to all of the women for your graceful cooperation in the heat of a typical Engare Sero day. Your interest, sincerity, and laughter gave my project life from the first day. -

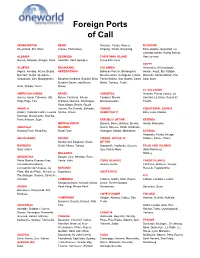

PORTS of CALL WORLDWIDE.Xlsx

Foreign Ports of Call AFGHANISTAN BENIN Shantou, Tianjin, Xiamen, ECUADOR Kheyrabad, Shir Khan Cotnou, Porto-Novo Xingang, Yantai, Zhanjiang Esmeraoldas, Guayaquil, La Libertad, Manta, Puerto Bolivar, ALBANIA BERMUDA CHRISTMAS ISLAND San Lorenzo Durres, Sarande, Shegjin, Vlore Hamilton, Saint George’s Flying Fish Cove EGYPT ALGERIA BOSNIAAND COLOMBIA Alexandria, Al Ghardaqah, Algiers, Annaba, Arzew, Bejaia, HERZEGOVINA Bahia de Portete, Barranquilla, Aswan, Asyut, Bur Safajah, Beni Saf, Dellys, Djendjene, Buenaventura, Cartagena, Leticia, Damietta, Marsa Matruh, Port Ghazaouet, Jijel, Mostaganem, Bosanka Gradiska, Bosakni Brod, Puerto Bolivar, San Andres, Santa Said, Suez Bosanki Samac, and Brcko, Marta, Tumaco, Turbo Oran, Skikda, Tenes Orasje EL SALVADOR AMERICAN SAMOA BRAZIL COMOROS Acajutla, Puerto Cutuco, La Aunu’u, Auasi, Faleosao, Ofu, Belem, Fortaleza, Ikheus, Fomboni, Moroni, Libertad, La Union, Puerto El Pago Pago, Ta’u Imbituba, Manaus, Paranagua, Moutsamoudou Triunfo Porto Alegre, Recife, Rio de ANGOLA Janeiro, Rio Grande, Salvador, CONGO, EQUATORIAL GUINEA Ambriz, Cabinda, Lobito, Luanda Santos, Vitoria DEMOCRATIC Bata, Luba, Malabo Malongo, Mocamedes, Namibe, Porto Amboim, Soyo REPUBLIC OF THE ERITREA BRITISH VIRGIN Banana, Boma, Bukavu, Bumba, Assab, Massawa ANGUILLA ISLANDS Goma, Kalemie, Kindu, Kinshasa, Blowing Point, Road Bay Road Town Kisangani, Matadi, Mbandaka ESTONIA Haapsalu, Kunda, Muuga, ANTIGUAAND BRUNEI CONGO, REPUBLIC Paldiski, Parnu, Tallinn Bandar Seri Begawan, Kuala OF THE BARBUDA Belait, Muara, Tutong -

Location Indicators by Indicator

ECCAIRS 4.2.6 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by indicator The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 12 January 2006 Page 1 of 251 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by Indicator Data Definition Standard OAAD OAAD : Amdar 1001 Afghanistan OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi 1002 Afghanistan OAAS OAAS : Asmar 1003 Afghanistan OABG OABG : Baghlan 1004 Afghanistan OABR OABR : Bamar 1005 Afghanistan OABN OABN : Bamyan 1006 Afghanistan OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan 1007 Afghanistan OABD OABD : Behsood 1008 Afghanistan OABT OABT : Bost 1009 Afghanistan OACC OACC : Chakhcharan 1010 Afghanistan OACB OACB : Charburjak 1011 Afghanistan OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof 1012 Afghanistan OADZ OADZ : Darwaz 1013 Afghanistan OADD OADD : Dawlatabad 1014 Afghanistan OAOO OAOO : Deshoo 1015 Afghanistan OADV OADV : Devar 1016 Afghanistan OARM OARM : Dilaram 1017 Afghanistan OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem 1018 Afghanistan OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad 1019 Afghanistan OAFR OAFR : Farah 1020 Afghanistan OAGD OAGD : Gader 1021 Afghanistan OAGZ OAGZ : Gardez 1022 Afghanistan OAGS OAGS : Gasar 1023 Afghanistan OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad 1024 Afghanistan OAGN OAGN : Ghazni 1025 Afghanistan OAGM OAGM : Ghelmeen 1026 Afghanistan OAGL OAGL : Gulistan 1027 Afghanistan OAHJ OAHJ : Hajigak 1028 Afghanistan OAHE OAHE : Hazrat eman 1029 Afghanistan OAHR OAHR : Herat 1030 Afghanistan OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala 1031 Afghanistan OAJS OAJS : Jabul saraj 1032 Afghanistan OAJL OAJL : Jalalabad 1033 Afghanistan OAJW OAJW : Jawand 1034 -

English Cop17 Inf. 47 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

Original language: English CoP17 Inf. 47 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 TRADE STUDY OF SELECTED EAST AFRICAN TIMBER PRODUCTION SPECIES This document has been submitted by Germany* in relation to agenda items 62, 77 and 88. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP17 Inf. 47 – p. 1 Anthony B. Cunningham Trade study of selected east African timber production species BfN-Skripten 445 2016 Trade study of selected east African timber production species Handelsstudie zu ostafrikanischen Holzarten (FKZ 3514 53 2003) Anthony B. Cunnigham Cover picture: A worker of a sawmill in front of Dalbergia melanoxylon logs in Montepuez/Mozambique (A.B. Cunningham) Author’s address: Dr. Anthony B. Cunningham Cunningham Consultancy WA Pty Ltd. 2 Tapper Street Au-6162 Fremantle E-Mail: [email protected] Scientific Supervision at BfN: Dr. Daniel Wolf Division II 1.2 “Plant Conservation“ This publication is included in the literature database “DNL-online” (www.dnl-online.de) BfN-Skripten are not available in book trade. Publisher: Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN) Federal Agency for Nature Conservation Konstantinstrasse 110 53179 Bonn, Germany URL: http://www.bfn.de The publisher takes no guarantee for correctness, details and completeness of statements and views in this report as well as no guarantee for respecting private rights of third parties. -

Title an Account of Intercultural Contact in Nyakyusa Personal

An Account of Intercultural Contact in Nyakyusa Personal Title Names Author(s) LUSEKELO, Amani Citation African Study Monographs (2018), 39(2): 47-67 Issue Date 2018-06 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/231403 Copyright by The Center for African Area Studies, Kyoto Right University, June 1, 2018. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 39(2): 47–67, June 2018 47 AN ACCOUNT OF INTERCULTURAL CONTACT IN NYAKYUSA PERSONAL NAMES Amani LUSEKELO Department of Languages and Literature, Dar es Salaam University College of Education, University of Dar es Salaam ABSTRACT The impact of intercultural contact in African societies may be well articulated by examining personal names bestowed to children. The contact between different cultures yields different naming systems, apparent in the trends in personal names of children in the Nyakyusa community in Tanzania. Qualitative analysis of a sample of 220 personal names col- lected by the author yielded three layers: a layer of names with words and clauses with meaning in Nyakyusa language, another layer of names starting with mwa- which indicates the descent of the family, and yet another layer of nativized English, Swahili and/or Christian names. The findings were consistent with another sample of 786 names of primary school pupils in rural areas, foreign names accounted for about 60 percent of all names outnumbering, by far, the in- digene names. It may follow that most parents in the Nyakyusa community opt for foreign names rather than native ones. This paper is a testimony that traditions in the Nyakyusa naming system are diminishing. Key Words: Intercultural contact; Languages-in-contact; Personal names; Nyakyusa; Tanzania. -

The Difficulties Experienced by Luo and Swahili Children

THE DIFFICULTIES EXPERIENCED BY LUO AND SWAHILI CHILDREN IN LEARNING ENG LISH by DONALD OWUOR. B~ A~ A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Department of Education, McGill University. Montreal. August, 1963. PREFACE The purpose of the dissertation is to locate, analyse and define the diliiculties which Luo and Swahili children· in the schools of Kenya experience when learning English, and to make sorne suggestions regarding the elimination of those difficulties. English is the official language of Kenya. It is also the language of instruc tion at alllevels of education above secondary school. It is important, therefore. that the teaching of English in the schools of Kenya be of the highest standard attainable. Sorne knowledge of the factors which influence the way African children learn Engllsh is essential if the standards of the teaching of English in Kenya are to be improved. I wish to express my indebtedness to Mr. B. J. Spolsky for his valuable suggestions and guidance throughout this study. I am also grateful to Prof. Reginald Edwards for the counsel and help I received from him. CONTENTS 1. CHAPTER 1 Introduction .......................... Page 1 2. CHAPTER II Luo and Swahili children at schoo1 •••••••••••••• • 17 (a) The schoo1 system • • ••••• . 18 (b} The LuQ child in the system •••••••• . 28 (c) The Swahili child in the system ••• . .. 35 (d) Sorne of their ex.ternal handicaps ••• . 39 3. CHAPTER ID The sounds of English, Luo_ and Swahili • • • • • • • • • • • 47 (a) The consonantal phonemes. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 50 (b) Consonant clusters • • • • • • • 60 (c) Vowel phonemes • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 63 4. -

Culture and Customs of Kenya

Culture and Customs of Kenya NEAL SOBANIA GREENWOOD PRESS Culture and Customs of Kenya Cities and towns of Kenya. Culture and Customs of Kenya 4 NEAL SOBANIA Culture and Customs of Africa Toyin Falola, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sobania, N. W. Culture and customs of Kenya / Neal Sobania. p. cm.––(Culture and customs of Africa, ISSN 1530–8367) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–31486–1 (alk. paper) 1. Ethnology––Kenya. 2. Kenya––Social life and customs. I. Title. II. Series. GN659.K4 .S63 2003 305.8´0096762––dc21 2002035219 British Library Cataloging in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2003 by Neal Sobania All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2002035219 ISBN: 0–313–31486–1 ISSN: 1530–8367 First published in 2003 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 For Liz Contents Series Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Chronology xvii 1 Introduction 1 2 Religion and Worldview 33 3 Literature, Film, and Media 61 4 Art, Architecture, and Housing 85 5 Cuisine and Traditional Dress 113 6 Gender Roles, Marriage, and Family 135 7 Social Customs and Lifestyle 159 8 Music and Dance 187 Glossary 211 Bibliographic Essay 217 Index 227 Series Foreword AFRICA is a vast continent, the second largest, after Asia.