Patrick Runkle Finished Draft December 10, 1997 Advisor: Donna Jo Napoli 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae (Minus Publications)

Curriculum Vitae (minus publications) Donna Jo Napoli Prof. of Linguistics and Social Justice Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA 19081 610-328-8422 (telephone)/ (610) 610-957-6167 (fax) [email protected] http://www.swarthmore.edu/donna-jo-napoli updated 20 September 2021 Education 1973-74 Visiting Scientist in Linguistics (postdoctoral year), MIT. 1973 Ph.D. General and Romance Linguistics (Dept. Romance Lgs & Lits Program A), Harvard University 1971 M.A Italian Literature, Harvard University 1970 A.B. Mathematics. Harvard University Teaching areas syntax, structure of American Sign Language, making bimodal-bilingual video-books to aid in deaf literacy, language matters with respect to Deaf people, linguistic creativity of taboo language, sign language literature from a linguistics perspective, oral and written language, narrative in language compared to dance/theater/ceramics and other arts, field linguistics, morphology, mathematical and linguistic analysis of folk dance, fiction writing workshops (USA and abroad) Employment and Professional Experience since coming to Swarthmore (in fall 1987) 1987–present Swarthmore College, Professor of Linguistics (chair 1987–2002), Professor of Linguistics and Social Justice as of fall 2018 2019 spring CNPQ Visiting Prof. at the University of Santa Caterina in Brazil. 2018 summer Served as Fulbright Specialist at the Universiteit Göttingen in Germany. 2015-16 summers Faculty at New York- St. Petersburg Institute of Linguistics, Cognition and Culture (collaboration of Stony Brook University and St. Petersburg State University in St. Petersburg, Russia) 2015 spr-sum Visiting Professor, Ca’Foscari, University of Venice, Italy; Fulbright Scholar, teaching at Siena School for Liberal Arts, Siena, Italy 2014 October Visiting Scholar to Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil (funded by CNPQ) 2013 fall Creative Writing Program, U. -

On the Linguistic Effects of Articulatory Ease, with a Focus on Sign Languages

Swarthmore College Works Linguistics Faculty Works Linguistics 6-1-2014 On The Linguistic Effects Of Articulatory Ease, With A Focus On Sign Languages Donna Jo Napoli Swarthmore College, [email protected] N. Sanders R. Wright Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-linguistics Part of the Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Donna Jo Napoli, N. Sanders, and R. Wright. (2014). "On The Linguistic Effects Of Articulatory Ease, With A Focus On Sign Languages". Language. Volume 90, Issue 2. 424-456. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-linguistics/39 This work is brought to you for free and open access by . It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2QWKHOLQJXLVWLFHIIHFWVRIDUWLFXODWRU\HDVHZLWKD IRFXVRQVLJQODQJXDJHV Donna Jo Napoli, Nathan Sanders, Rebecca Wright Language, Volume 90, Number 2, June 2014, pp. 424-456 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\/LQJXLVWLF6RFLHW\RI$PHULFD DOI: 10.1353/lan.2014.0026 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lan/summary/v090/90.2.napoli.html Access provided by Swarthmore College (4 Dec 2014 12:18 GMT) ON THE LINGUISTIC EFFECTS OF ARTICULATORY EASE, WITH A FOCUS ON SIGN LANGUAGES Donna Jo Napoli Nathan Sanders Rebecca Wright Swarthmore College Swarthmore College Swarthmore College Spoken language has a well-known drive for ease of articulation, which Kirchner (1998, 2004) analyzes as reduction of the total magnitude of all biomechanical forces involved. We extend Kirchner’s insights from vocal articulation to manual articulation, with a focus on joint usage, and we discuss ways that articulatory ease might be realized in sign languages. -

An Optimality Theoretic Analysis of Rising Changed Tones in Taishanese

An Optimality Theoretic Analysis of Rising Changed Tones in Taishanese Kevin Liang, University of Pennsylvania Taishanese is a member of the Siyi sub-branch of the Yue branch of the Sinitic languages. As described by Taishan Fangyin Zidian (2006), Taishanese has five phonemic tones: three level tones (55, 33, 22) and two falling tones (32, 21). Cheng (1973) describes a so-called “changed tone” process where the tonal contour of the underlying tones can be modified. Depending on the morphological or syntactic context, one of two processes can occur: a level or falling tone becomes a rising tone; or a level tone becomes a falling tone. The present work focuses on the former type of changed tone where a rising tone, which is otherwise not present in Taishanese, can be realized. In the present study, Taishanese tone letter 5 will be represented as H (a tone with the features [+high tone][-low tone][+modify]), tone letter 3 as M (a tone with the features [-high tone][-low tone][-modify]), and tone letter 2 as L (a tone with the features [-high tone][+low tone][+modify]). This is based on the system proposed by Wang (1967) and Woo (1969). Early work on rising changed tones in Taishanese, such as in Cheng (1973), claimed that the process was not phonologically motivated but mostly syntactically and morphologically motivated. Moreover, according to Cheng (1973), only a limited number of words, which are mostly nouns, can undergo this process. However, Him (1980) suggests that the rising changed tone in Taishanese may be the result of an operative process where rises can occur systematically, based on an analysis of related languages. -

Appendix D Children’S Literature Related to Math Concepts

cd04_4435.qxd 7/18/05 4:01 PM Page 101 Appendix D Children’s Literature Related to Math Concepts Integrating literature into mathematics lessons helps students see math concepts in context and presents an engaging and memorable way to explore skills. A list of children’s literature that relates to important mathematics concepts follows. They can be used to read aloud to students, to engage students in reading along with you, or for independent reading at centers or in class- room libraries. A piece of literature is often useful at a variety of grade levels depending on whether it is to be read to students or for them to read on their own, and/or whether it is intended to intro- duce a concept or to provide reinforcement or enrichment of a previously learned skill. Follow- ing each book reference (title, author, publisher, date), you will find the letters P (primary grades K–2) and/or I (intermediate grades 3–6)—or both—to indicate grade levels in which the book might be an appropriate addition to your math classroom. Addition Animals on Board. Stuart J. Murphy. HarperCollins, 1998. (P) A Collection for Kate. Barbara deRubertis. Kane Publishing, 1999. (P/I) A Fair Bear Share. Stuart J. Murphy. HarperCollins, 1998. (P/I) Fish Eyes. Lois Ehlert. Voyager/HBJ, 1990. (P) Just Enough Carrots. Stuart J. Murphy. HarperCollins, 1997. (P) Mission Addition. Loreen Leedy. Holiday House, 1997. (P/I) Mouse Count. Ellen Stoll Walsh. Harcourt Brace & Co., 1991. (P) The Napping House. Audrey Wood. Harcourt Brace, 1984. (P) 12 Ways to Get to 11. -

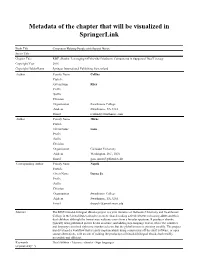

Metadata of the Chapter That Will Be Visualized in Springerlink

Metadata of the chapter that will be visualized in SpringerLink Book Title Computers Helping People with Special Needs Series Title Chapter Title RISE eBooks: Leveraging Off-the-Shelf Software Components in Support of Deaf Literacy Copyright Year 2016 Copyright HolderName Springer International Publishing Switzerland Author Family Name Collins Particle Given Name Riley Prefix Suffix Division Organization Swarthmore College Address Swarthmore, PA, USA Email [email protected] Author Family Name Mirus Particle Given Name Gene Prefix Suffix Division Organization Gallaudet University Address Washington, D.C., USA Email [email protected] Corresponding Author Family Name Napoli Particle Given Name Donna Jo Prefix Suffix Division Organization Swarthmore College Address Swarthmore, PA, USA Email [email protected] Abstract The RISE bimodal-bilingual eBooks project is a joint initiative of Gallaudet University and Swarthmore College in the United States aimed to promote shared reading activities between hearing adults and their deaf children, although the format may welcome users from a broader spectrum. It produces ebooks, typically using published picture books as a base, and adding sign language videos, where the countries and languages involved right now number a dozen, but the global interest is growing steadily. The project has developed a workflow that is easily implementable using commercial off-the-shelf software, or open source alternatives, with an aim of making the production of bimodal-bilingual ebooks both readily accessible and efficient. Keywords Deaf children - Literacy - ebooks - Sign languages (separated by '-') RISE eBooks: Leveraging Off-the-Shelf Software Components in Support of Deaf Literacy Author Proof Riley Collins1, Gene Mirus2, and Donna Jo Napoli1(✉) 1 Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA, USA [email protected], [email protected] 2 Gallaudet University, Washington, D.C., USA [email protected] Abstract. -

Evidence from 24 Sign Languages Nathan

1 A cross-linguistic preference for torso stability in the lexicon: Evidence from 24 sign languages Nathan Sandersa and Donna Jo Napolib aDepartment of Linguistics, Haverford College / bDepartment of Linguistics, Swarthmore College When the arms move in certain ways, they can cause the torso to twist or rock. Such extraneous torso movement is undesirable, especially during sign language communication, when torso position may carry linguistic significance, so we expend effort to resist it when it is not intended. This so-called “reactive effort” has only recently been identified by Sanders and Napoli (2016), but their preliminary work on three genetically unrelated languages suggests that the effects of reactive effort can be observed cross-linguistically by examination of sign language lexicons. In particular, the frequency of different kinds of manual movements in the lexicon correlates with the amount of reactive effort needed to resist movement of the torso. Following this line of research, we present evidence from 24 sign languages confirming that there is a cross-linguistic preference for minimizing the reactive effort needed to keep the torso stable. Keywords: sign languages, phonetics, ease of articulation, lexical frequency, linguistic universals 1. Introduction The many insights we have gained into the phonetics of spoken languages do not directly tell us much about the phonetics of sign languages, because of the inherent differences in the physical properties of the two modalities. Even for the fundamental concept of articulatory effort (defined generally as the sum of all articulatory forces; Kirchner 1998, 2004), the focus in phonetics has historically been only on the active effort used to move an articulator, because that is the type of articulatory effort most apparent in spoken language (Sanders & Napoli 2016:277). -

REACTIVE EFFORT AS a FACTOR THAT SHAPES SIGN LANGUAGE LEXICONS Nathan Sanders Donna Jo Napoli

REACTIVE EFFORT AS A FACTOR THAT SHAPES SIGN LANGUAGE LEXICONS Nathan Sanders Donna Jo Napoli Swarthmore College Swarthmore College Many properties of languages, including sign languages, are not uniformly distributed among items in the lexicon . Some of this nonuniformity can be accounted for by appeal to articulatory ease, with easier articulations being overrepresented in the lexicon in comparison to more difficult articulations. The literature on ease of articulation deals only with the active effort internal to the articulation itself. We note the existence of a previously unstudied aspect of articulatory ease, which we call reactive effort : the effort of resisting incidental movement that has been induced by an articulation elsewhere in the body. For example, reactive effort is needed to resist incidental twisting and rocking of the torso induced by path movement of the manual articulators in sign lan - guages. We argue that, as part of a general linguistic drive to reduce articulatory effort, reactive ef - fort should have a significant effect on the relative frequency in the lexicon of certain types of path movements. We support this argument with evidence from Italian Sign Language, Sri Lankan Sign Language, and Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language, evidence that cannot be explained solely by appeal to constraints on bimanual coordination . As the first exploration of the linguistic role of re - active effort, this work contributes not only to the developing field of sign language phonetics, but also to our understanding of phonetics in general , adding to a growing body of functionalist liter - ature showing that some linguistic patterns emerge from more fundamental factors of the physical world. -

Italian-American Literature

Italian-American Literature: Respected? by Donna Jo Napoli ABSTRACT: Italian-American literature is among the various disrespected literatures in the United States. That point is easily made here, via a brief overview of how relevant publications have been received. What is more difficult to understand is why. I offer a personal account of my own upbringing in the Jim Crow south, as well as a chapter from my young adult novel that is set a half century before I was born and that gives a sense of the prejudice that forms the underpinnings of this disrespect. KEY WORDS: Italian-American experience; Jim Crow south; linguistic prejudice; racism I’m Italian-American. So what am I doing in this particular issue of Altre Modernità? Feeling my way a tastoni—with the grope of someone in a fog. I’ll try to explain. Accompanying this essay is Chapter Three of my young adult novel Alligator Bayou, reprinted with the kind permission of Penguin Random House. The novel is based on true events that led up to the lynching of five Italians and Italian-Americans in the American city of Tallulah, Louisiana, in 1899. The main character is a fourteen- year-old Sicilian boy, who constituted a fictional sixth person in the group of Italians I Creativi/Hacedores/ Les Créatifs /The Creative N. 22 – 11/2019 182 living there at that time. This was a situation in which plantation owners kept former slaves and children of former slaves on as employees who worked the land. Those employees bought their foods and other necessities from stores owned by the plantation owners, which meant they were either in debt or barely meeting their expenses, so they weren’t free to leave their jobs. -

For Adults for Adults for Teens for Children for Children

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS Remembering September 11 Teens Remember FOR CHILDREN The FOR CHILDREN THE BOOK911 O September 11 F HELP Hiking on Long Island Anxiety & Phobias Documenting Reference Resources In August, teens participated A Special Opportunity Story Parade Bookmark Spot September 11, 2002 will mark one year since (N) Wednesdays, 4:00 p.m. Stop by the Library (N) Monday, September 23, (N) Tuesday, September 24, 7:30 p.m. Our in a book discussion of 911: The for Fifth Graders! and pick up September’s FIRESIDE FRIDAY 7:30 p.m. Anxiety (exaggerated worry) and phobias (persistent the horrifi c attacks on the World Trade Center and Book of Help with editor Marc Session I: October 2, 9, 16 & 23 bookmark by Elizabeth Community: Meet Donna Jo Napoli, author of The Lee McAllister, a member of the fears of an object or situation) often accompany depres- the Pentagon, as well as the the plane crash in Penn- Aronson and author Marina Session II: November 13, 20, Dec. 4 & Jerome. A reading list, com- AUTHORS RESP Bravest Thing, Changing Tunes, Jimmy Hi-Fa-lutin’ Long Island Greenbelt Trail Con- sion and lead people to seek professional help. Dr. Julian A Digitization sylvania. Our Reference Librarians have compiled Budhos. The book, a collection of TO OND 11 piled by our Children’s THE TRAGEDY the Pickpocket of the Palace, (EN) Friday, September 27, 7:30 p.m. ference and author of Hiking the Herskowitz, a psychologist who specializes in the treat- articles from web sites, newspapers, and magazines essays, stories, and poems Register September 18 at Northport. -

Clash Avoidance in Italian* Irenie Vogel

Linguistic Inquiry Volume 10 Number 3 (Summer, 1979) 467-482. Marina Nespor, Clash Avoidance in Italian* Irenie Vogel 0. Introduction 0. 1. Background In a recent article, Liberman and Prince (1977) (hereafter L&P) have proposed that stress be interpreted in terms of the relative prominence of the various elements in a given structure (foot, word, phrase) rather than as an absolute integer value as proposed in The Soun1d Pattern of English (Chomsky and Halle (1968)). L&P's theory claims further that "the perceived 'stressing' of an utterance . reflects the combined influ- ence of a constituent-structure pattern and its grid alignment" (p. 249). This analysis gives new insights into much-studied problems of English stress assignment. In partic- ular, it accounts for such phenomena as the retraction of stress in the (now classic) example thirteen but thhirteenmen. This retraction is shown to be a readjustment of the stress pattern in order to avoid what L&P term a "clash", that is, a specific grid configuration determined by a combination of constituent structure and grid alignment principles in which "perniciously close" stresses appear. As L&P point out, such stress readjustment rules or "rhythm rules" appear to be "reasonably natural phenomena", and it therefore remains for linguists to examine instances of such patterns in other languages in order to determine (a) what specific "stress configurations are marked as Iclashing', thus producing a pressutre for change" and (b) under what specific circum- stances "a given language grants perinission for such a change to occur" (p. 31 1). This article is devoted to an analysis of a stress readjustment pattern we have observed in certain varieties of standard Italian. -

Journal of Linguistics Gaurav Mathur & Donna Jo Napoli (Eds.), Deaf

Journal of Linguistics http://journals.cambridge.org/LIN Additional services for Journal of Linguistics: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Gaurav Mathur & Donna Jo Napoli (eds.), Deaf around the world: The impact of language. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. Pp. xviii +398. Connie de Vos and Nick Palfreyman Journal of Linguistics / Volume 48 / Issue 03 / November 2012, pp 731 735 DOI: 10.1017/S0022226712000291, Published online: Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0022226712000291 How to cite this article: Connie de Vos and Nick Palfreyman (2012). Review of Gaurav Mathur, and Donna Jo Napoli 'Deaf around the world: The impact of language' Journal of Linguistics, 48, pp 731735 doi:10.1017/S0022226712000291 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/LIN, IP address: 192.87.79.51 on 24 Oct 2012 REVIEWS Bosˇkovic´,Zˇ eljko. 2008. What will you have, DP or NP? In Emily Elfner & Martin Walkow (eds.), The North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 37.1, 101–114. Longobardi, Giuseppe. 1994. Reference and proper names: A theory of N-movement in syntax and logical form. Linguistic Inquiry 25.4, 609–665. Pereltsvaig, Asya. 2008. Split phrases in colloquial Russian. Studia Linguistica 62.1, 5–38. Pereltsvaig, Asya. Forthcoming. Noun Phrase structure in article-less Slavic languages: DP or not DP? Linguistics and Language Compass. Wiley Online Library. Rappaport, Gilbert C. 2001. Extraction from nominal phrases in Polish and the theory of de- terminers. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 8.3, 159–198. Author’s address: Department of Linguistics, Stanford University, Margaret Jacks Hall, Building 460, Stanford CA 94305-2150, USA [email protected] (Received 18 July 2012) J. -

Developing Language and (Pre) Literacy Skills in Deaf Preschoolers

Journal of Multilingual Education Research Volume 8 Article 10 2018 Developing Language and (Pre)literacySkills in Deaf Preschoolers through Shared Reading Activities with Bimodal-Bilingual eBooks Gene Mirus Gallaudet University, [email protected] Donna Jo Napoli Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jmer Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, Language and Literacy Education Commons, and the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Mirus, Gene and Napoli, Donna Jo (2018) "Developing Language and (Pre)literacySkills in Deaf Preschoolers through Shared Reading Activities with Bimodal-Bilingual eBooks," Journal of Multilingual Education Research: Vol. 8 , Article 10. Available at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jmer/vol8/iss1/10 This Article on Practice is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Multilingual Education Research by an authorized editor of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Developing Language and (Pre)literacySkills in Deaf Preschoolers through Shared Reading Activities with Bimodal-Bilingual eBooks Cover Page Footnote Financial disclosure: Neither author has any financial interests to disclose. We adopt the usual convention of using small capitals to indicate signs. We adopt the usual convention of using hyphens between letters to indicate fingerspelling. Gene Mirus, PhD, is Associate Professor of ASL and Deaf Studies at Gallaudet University. Through his doctoral training in linguistic anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin (2005), he developed a strong interest in studying the relationship between technology and language---specifically how various new technologies contributed to new language practices among Deaf users.