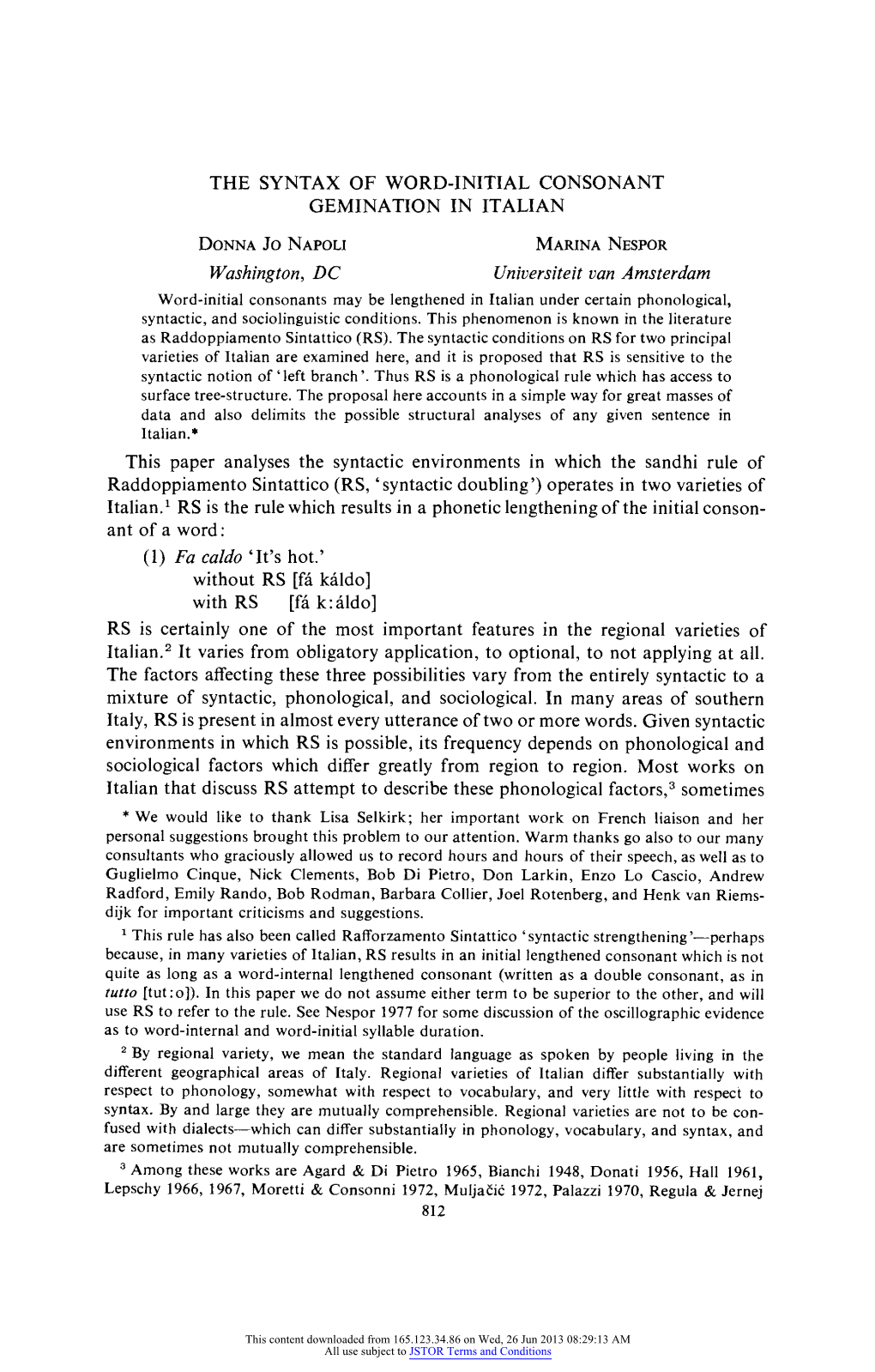

The Syntax of Word-Initial Consonant Gemination in Italian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downstep and Recursive Phonological Phrases in Bàsàá (Bantu A43) Fatima Hamlaoui ZAS, Berlin; University of Toronto Emmanuel-Moselly Makasso ZAS, Berlin

Chapter 9 Downstep and recursive phonological phrases in Bàsàá (Bantu A43) Fatima Hamlaoui ZAS, Berlin; University of Toronto Emmanuel-Moselly Makasso ZAS, Berlin This paper identifies contexts in which a downstep is realized between consecu- tive H tones in absence of an intervening L tone in Bàsàá (Bantu A43, Cameroon). Based on evidence from simple sentences, we propose that this type of downstep is indicative of recursive prosodic phrasing. In particular, we propose that a down- step occurs between the phonological phrases that are immediately dominated by a maximal phonological phrase (휙max). 1 Introduction In their book on the relation between tone and intonation in African languages, Downing & Rialland (2016) describe the study of downtrends as almost being a field in itself in the field of prosody. In line with the considerable literature on the topic, they offer the following decomposition of downtrends: 1. Declination 2. Downdrift (or ‘automatic downstep’) 3. Downstep (or ‘non-automatic downstep’) 4. Final lowering 5. Register compression/expansion or register lowering/raising Fatima Hamlaoui & Emmanuel-Moselly Makasso. 2019. Downstep and recursive phonological phrases in Bàsàá (Bantu A43). In Emily Clem, Peter Jenks & Hannah Sande (eds.), Theory and description in African Linguistics: Selected papers from the47th Annual Conference on African Linguistics, 155–175. Berlin: Language Science Press. DOI:10.5281/zenodo.3367136 Fatima Hamlaoui & Emmanuel-Moselly Makasso In the present paper, which concentrates on Bàsàá, a Narrow Bantu language (A43 in Guthrie’s classification) spoken in the Centre and Littoral regions of Cameroon by approx. 300,000 speakers (Lewis et al. 2015), we will first briefly define and discuss declination and downdrift, as the language displays bothphe- nomena. -

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M. Hyman 5.1. Introduction The historical relation between African and general phonology has been a mutu- ally beneficial one: the languages of the African continent provide some of the most interesting and, at times, unusual phonological phenomena, which have con- tributed to the development of phonology in quite central ways. This has been made possible by the careful descriptive work that has been done on African lan- guages, by linguists and non-linguists, and by Africanists and non-Africanists who have peeked in from time to time. Except for the click consonants of the Khoisan languages (which spill over onto some neighboring Bantu languages that have “borrowed” them), the phonological phenomena found in African languages are usually duplicated elsewhere on the globe, though not always in as concen- trated a fashion. The vast majority of African languages are tonal, and many also have vowel harmony (especially vowel height harmony and advanced tongue root [ATR] harmony). Not surprisingly, then, African languages have figured dispro- portionately in theoretical treatments of these two phenomena. On the other hand, if there is a phonological property where African languages are underrepresented, it would have to be stress systems – which rarely, if ever, achieve the complexity found in other (mostly non-tonal) languages. However, it should be noted that the languages of Africa have contributed significantly to virtually every other aspect of general phonology, and that the various developments of phonological theory have in turn often greatly contributed to a better understanding of the phonologies of African languages. Given the considerable diversity of the properties found in different parts of the continent, as well as in different genetic groups or areas, it will not be possible to provide a complete account of the phonological phenomena typically found in African languages, overviews of which are available in such works as Creissels (1994) and Clements (2000). -

Language Acquisition, Processing and Bilingualism

Language Acquisition, Processing and Bilingualism Language Acquisition, Processing and Bilingualism: Selected Papers from the Romance Turn VII Edited by Anna Cardinaletti, Chiara Branchini, Giuliana Giusti and Francesca Volpato Language Acquisition, Processing and Bilingualism: Selected Papers from the Romance Turn VII Edited by Anna Cardinaletti, Chiara Branchini, Giuliana Giusti and Francesca Volpato This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Anna Cardinaletti, Chiara Branchini, Giuliana Giusti, Francesca Volpato and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5065-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5065-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................... vii Anna Cardinaletti, Chiara Branchini, Giuliana Giusti and Francesca Volpato PART I: LANGUAGE PROCESSING IN ACQUISITION Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Rhythm and L2 Acquisition Marina Nespor and Alan Langus Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

The Colon As a Separate Prosodic Category: Tonal Evidence from Paicî (Oceanic, New Caledonia)

The Colon as a Separate Prosodic Category: Tonal Evidence from Paicî (Oceanic, New Caledonia) Florian Lionnet 1. Introduction This paper presents new evidence supporting the inclusion of the colon (κ) as a separate category in the Prosodic Hierarchy, on the basis of tonal data from Paicî, an Oceanic language of New Caledonia. The colon is a constituent intermediate between the foot and the word, made of two feet, as schematized in (1) (Stowell 1979; Halle & Clements 1983: 18-19; Hammond 1987; Hayes 1995: 119; Green 1997; a.o.). (1) Prosodic Word (!) [{(σσ)F t(σσ)F t}κ]! | Colon (κ) {(σσ)F t(σσ)F t}κ | Foot (F t) (σσ)F t(σσ)F t | Syllable (σ) σσσσ | Mora (µ) Justification for the colon (κ) rests mostly on the existence of tertiary stress. As clearly summarized by Green (1997: 102), “it is clear that in order to derive four levels of stress (primary, secondary, tertiary, unstressed), four levels of structure (prosodic word, colon, foot, syllable) are called for.” Colon-based analyses have so far been proposed for a dozen languages, listed in (2) below. (2) a. Passamaquoddy (Stowell 1979; Hayes 1995: 215-216; Green 1997: 104-109), b. Tiberian Hebrew (Dresher 1981), c. Garawa (Halle & Clements 1983: 20-21; Halle & Vergnaud 1987: 43; Hayes 1995: 202), d. Hungarian (Hammond 1987; Hayes 1995: 330; Green 1997: 102-104), e. Maithili (Hayes 1995: 149-162), f. Eastern Ojibwa (Hayes 1995: 216-218; Green 1997: 109-112), g. Asheninca (Hayes 1995: 288-296; Green 1997 112-114), h. the Neo-Štokavian dialect of Serbo-Croatian (Green 1997: 115-116), i. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Morphological Sources of Phonological Length

Morphological Sources of Phonological Length by Anne Pycha B.A. (Brown University) 1993 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2004 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Sharon Inkelas (chair) Professor Larry Hyman Professor Keith Johnson Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2008 Abstract Morphological Sources of Phonological Length by Anne Pycha Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Sharon Inkelas, Chair This study presents and defends Resizing Theory, whose claim is that the overall size of a morpheme can serve as a basic unit of analysis for phonological alternations. Morphemes can increase their size by any number of strategies -- epenthesizing new segments, for example, or devoicing an existing segment (and thereby increasing its phonetic duration) -- but it is the fact of an increase, and not the particular strategy used to implement it, which is linguistically significant. Resizing Theory has some overlap with theories of fortition and lenition, but differs in that it uses the independently- verifiable parameter of size in place of an ad-hoc concept of “strength” and thereby encompasses a much greater range of phonological alternations. The theory makes three major predictions, each of which is supported with cross-linguistic evidence. First, seemingly disparate phonological alternations can achieve identical morphological effects, but only if they trigger the same direction of change in a morpheme’s size. Second, morpheme interactions can take complete control over phonological outputs, determining surface outputs when traditional features and segments fail to do so. -

49 Stress-Timed Vs. Syllable- Timed Languages

TBC_049.qxd 7/13/10 19:21 Page 1 49 Stress-timed vs. Syllable- timed Languages Marina Nespor Mohinish Shukla Jacques Mehler 1Introduction Rhythm characterizes most natural phenomena: heartbeats have a rhythmic organization, and so do the waves of the sea, the alternation of day and night, and bird songs. Language is yet another natural phenomenon that is charac- terized by rhythm. What is rhythm? Is it possible to give a general enough definition of rhythm to include all the phenomena we just mentioned? The origin of the word rhythm is the Greek word osh[óp, derived from the verb oeí, which means ‘to flow’. We could say that rhythm determines the flow of different phenomena. Plato (The Laws, book II: 93) gave a very general – and in our opinion the most beautiful – definition of rhythm: “rhythm is order in movement.” In order to under- stand how rhythm is instantiated in different natural phenomena, including language, it is necessary to discover the elements responsible for it in each single case. Thus the question we address is: which elements establish order in linguistic rhythm, i.e. in the flow of speech? 2The rhythmic hierarchy: Rhythm as alternation Rhythm is hierarchical in nature in language, as it is in music. According to the metrical grid theory, i.e. the representation of linguistic rhythm within Generative Grammar (cf., amongst others, Liberman & Prince 1977; Prince 1983; Nespor & Vogel 1989; chapter 43: representations of word stress), the element that “establishes order” in the flow of speech is stress: universally, stressed and unstressed positions alternate at different levels of the hierarchy (see chapter 40: stress: phonotactic and phonetic evidence). -

Curriculum Vitae

Donna Jo Napoli -- Publications Academic Publications: Books and one edited full issue of a journal 18. Disrespected literatures: Histories and reversal of linguistic oppression. Issue 22 of Altre Modernità, 2019. https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/AMonline/issue/view/1451 (Co-editor with Simona Bertacco and Rachel Sutton-Spence). 17. Primary movement in sign languages: a study of six languages. (Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 2011). (with Mark Mai and Nicholas Gaw) 16. Deaf around the world: The impact of language. (Oxford: Oxford U. Press, 2010). (Co-editor with Gaurav Mathur) 15. Language matters, second edition (Oxford: Oxford U. Press, 2010) (coauthor with Vera Lee- Schoenfeld) 14. Humour in sign languages: The linguistic underpinnings. (Dublin: Trinity College, 2009). (with Rachel Sutton-Spence) 13. Access: Multiple avenues for deaf people. (Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet U. Press, 2008), (coeditor with Doreen DeLuca, Irene Leigh, and Kristin Lindgren). 12. Signs and voices: Deaf matters in language, arts, and identity. (Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet U. Press, 2008). (Co-editor with Doreen DeLuca and Kristin Lindgren). 11. L'animale parlante. (Roma: Casa Editrice Carocci, 2004). (with Marina Nespor) 10. Language matters. (Oxford: Oxford U. Press, 2003; in Korean with Thaehaksa Publishing Co.). 9. Linguistics: Theory and problems. (Oxford: Oxford U. Press, 1996). 8. A prosodic template in historical change: The passage of the Latin second conjugation into Romance (Torino: Rosenberg and Sellier. 1994). (with Stuart Davis) 7. Syntax: Theory and Problems. (Oxford: Oxford U. Press, 1993). 6. Bridges between psychology and linguistics: A Swarthmore festschrift for Lila Gleitman. (Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1991). -

How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F

Language and Linguistics Compass 2/6 (2008): 1149–1170, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00089.x How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F. Werker University of British Columbia Abstract Perceiving the acoustic signal as a sequence of meaningful linguistic representations is a challenging task, which infants seem to accomplish effortlessly, despite the fact that they do not have a fully developed knowledge of language. The present article takes an integrative approach to infant speech perception, emphasizing how young learners’ perception of speech helps them acquire abstract structural properties of language. We introduce what is known about infants’ perception of language at birth. Then, we will discuss how perception develops during the first 2 years of life and describe some general perceptual mechanisms whose importance for speech perception and language acquisition has recently been established. To conclude, we discuss the implications of these empirical findings for language acquisition. 1. Introduction As part of our everyday life, we routinely interact with children and adults, women and men, as well as speakers using a dialect different from our own. We might talk to them face-to-face or on the phone, in a quiet room or on a busy street. Although the speech signal we receive in these situations can be physically very different (e.g., men have a lower-pitched voice than women or children), we usually have little difficulty understanding what our interlocutors say. Yet, this is no easy task, because the mapping from the acoustic signal to the sounds or words of a language is not straightforward. -

Curriculum Vitae (Minus Publications)

Curriculum Vitae (minus publications) Donna Jo Napoli Prof. of Linguistics and Social Justice Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA 19081 610-328-8422 (telephone)/ (610) 610-957-6167 (fax) [email protected] http://www.swarthmore.edu/donna-jo-napoli updated 20 September 2021 Education 1973-74 Visiting Scientist in Linguistics (postdoctoral year), MIT. 1973 Ph.D. General and Romance Linguistics (Dept. Romance Lgs & Lits Program A), Harvard University 1971 M.A Italian Literature, Harvard University 1970 A.B. Mathematics. Harvard University Teaching areas syntax, structure of American Sign Language, making bimodal-bilingual video-books to aid in deaf literacy, language matters with respect to Deaf people, linguistic creativity of taboo language, sign language literature from a linguistics perspective, oral and written language, narrative in language compared to dance/theater/ceramics and other arts, field linguistics, morphology, mathematical and linguistic analysis of folk dance, fiction writing workshops (USA and abroad) Employment and Professional Experience since coming to Swarthmore (in fall 1987) 1987–present Swarthmore College, Professor of Linguistics (chair 1987–2002), Professor of Linguistics and Social Justice as of fall 2018 2019 spring CNPQ Visiting Prof. at the University of Santa Caterina in Brazil. 2018 summer Served as Fulbright Specialist at the Universiteit Göttingen in Germany. 2015-16 summers Faculty at New York- St. Petersburg Institute of Linguistics, Cognition and Culture (collaboration of Stony Brook University and St. Petersburg State University in St. Petersburg, Russia) 2015 spr-sum Visiting Professor, Ca’Foscari, University of Venice, Italy; Fulbright Scholar, teaching at Siena School for Liberal Arts, Siena, Italy 2014 October Visiting Scholar to Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil (funded by CNPQ) 2013 fall Creative Writing Program, U. -

On the Linguistic Effects of Articulatory Ease, with a Focus on Sign Languages

Swarthmore College Works Linguistics Faculty Works Linguistics 6-1-2014 On The Linguistic Effects Of Articulatory Ease, With A Focus On Sign Languages Donna Jo Napoli Swarthmore College, [email protected] N. Sanders R. Wright Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-linguistics Part of the Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Donna Jo Napoli, N. Sanders, and R. Wright. (2014). "On The Linguistic Effects Of Articulatory Ease, With A Focus On Sign Languages". Language. Volume 90, Issue 2. 424-456. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-linguistics/39 This work is brought to you for free and open access by . It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2QWKHOLQJXLVWLFHIIHFWVRIDUWLFXODWRU\HDVHZLWKD IRFXVRQVLJQODQJXDJHV Donna Jo Napoli, Nathan Sanders, Rebecca Wright Language, Volume 90, Number 2, June 2014, pp. 424-456 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\/LQJXLVWLF6RFLHW\RI$PHULFD DOI: 10.1353/lan.2014.0026 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lan/summary/v090/90.2.napoli.html Access provided by Swarthmore College (4 Dec 2014 12:18 GMT) ON THE LINGUISTIC EFFECTS OF ARTICULATORY EASE, WITH A FOCUS ON SIGN LANGUAGES Donna Jo Napoli Nathan Sanders Rebecca Wright Swarthmore College Swarthmore College Swarthmore College Spoken language has a well-known drive for ease of articulation, which Kirchner (1998, 2004) analyzes as reduction of the total magnitude of all biomechanical forces involved. We extend Kirchner’s insights from vocal articulation to manual articulation, with a focus on joint usage, and we discuss ways that articulatory ease might be realized in sign languages. -

An Optimality Theoretic Analysis of Rising Changed Tones in Taishanese

An Optimality Theoretic Analysis of Rising Changed Tones in Taishanese Kevin Liang, University of Pennsylvania Taishanese is a member of the Siyi sub-branch of the Yue branch of the Sinitic languages. As described by Taishan Fangyin Zidian (2006), Taishanese has five phonemic tones: three level tones (55, 33, 22) and two falling tones (32, 21). Cheng (1973) describes a so-called “changed tone” process where the tonal contour of the underlying tones can be modified. Depending on the morphological or syntactic context, one of two processes can occur: a level or falling tone becomes a rising tone; or a level tone becomes a falling tone. The present work focuses on the former type of changed tone where a rising tone, which is otherwise not present in Taishanese, can be realized. In the present study, Taishanese tone letter 5 will be represented as H (a tone with the features [+high tone][-low tone][+modify]), tone letter 3 as M (a tone with the features [-high tone][-low tone][-modify]), and tone letter 2 as L (a tone with the features [-high tone][+low tone][+modify]). This is based on the system proposed by Wang (1967) and Woo (1969). Early work on rising changed tones in Taishanese, such as in Cheng (1973), claimed that the process was not phonologically motivated but mostly syntactically and morphologically motivated. Moreover, according to Cheng (1973), only a limited number of words, which are mostly nouns, can undergo this process. However, Him (1980) suggests that the rising changed tone in Taishanese may be the result of an operative process where rises can occur systematically, based on an analysis of related languages.