Nancy Adajania | Public Art? 03/01/11 11:30 AM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibition Brochure

‘Now that the trees have spoken’ Ranjit Hoskote ‘Now that the trees have spoken’ presents the work of four artists: Bhuri Bai, Ladoo Bai, Narmada Prasad Tekam and Ram Singh Urveti. Their paintings, which are being exhibited in Mumbai for the first time, form part of a collection built up over the last five years by Dadiba Pundole. They way-mark the process of dialogue that this Bombay-based gallerist and collector has enjoyed with the artists, in the course of his research trips into central India. Born and raised in Madhya Pradesh, the protagonists of ‘Now that the trees have spoken’ represent that emergent third field of artistic production in contemporary Indian culture which is neither metropolitan nor rural, neither (post)modernist nor traditional, neither derived from academic training nor inherited without change from tribal custom. Indeed, as theorists and curators actively engaged with mapping this third field (including J Swaminathan, Jyotindra Jain, Gulammohammed Sheikh and Nancy Adajania) have demonstrated, descriptions such as ‘tribal’ and ‘folk’, although still used as convenient shorthand, are worse than useless. Generated from the typological obsessions of the colonial census, these labels have long been responsible for a dreadful incarceration. They have reduced thousands of individuals to the happenstance of birth, registering them primarily as bearers of community identities rather than as citizens of a Republic. And, once circumscribed as Warlis, Bhils, Gonds or Saoras, these individuals have had to mortgage their free-floating, self-renewing imaginative energies to the regime of the emporium. None of the four artists presented in ‘Now that the trees have spoken’ inherits a primordial ‘folk art’. -

Twenty-Third International Congress of Vedanta August 10-13, 2017

Twenty - Third International Congress of Vedanta August 10 - 13, 2017 On August 10 - 13, 2017 the Twenty - Third International Congress of Vedanta was hosted by T he Center for Indic Studies, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, USA in collaboration with the Institute of Advanced Sciences, Dartmouth, USA . The inauguration session started in the morning of first day with Vedic c hanting performed by Swami Yogatmananda, Vedanta Society of Providence, and Swami Atmajnanananda, Vedanta Center of Greater Washington , DC . Welcome address and i ntroduction presented by Conference Director Prof. Sukalyan Sengupta, University of Massachusetts , Dartmouth. Founding Director, Vedanta Congress Prof. S.S. Ramarao Pappu was felicitated in this session. Conference started with an inaugural l ecture by Mr. Rajeev Srinivasan on “ Leveraging the Grand Dharmic Narrative for Soft Power ”. Dr. Alex Hankey, SVYASA Bangalore and Dr. Makarand Paranjape, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New D elhi were the keynote speakers during this inaugural session . They deliver ed their talk s on “ Synthesizing Vedic and Modern Theories to Explain Cognition of Forms ” and “ Vedanta and Aesthetics ” , respectively. This session was concluded under the chairmanship of Prof. Raghwendra P . Singh, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. Inaugural Session, 23 rd International Vedanta Congress The Vedanta Congress continues its tradition of bringing scholars of Indic traditions from India and the West together on a platform nearly from three decades. Delegates from various -

Ranjit Hoskote: Signposting the Indian Highway Ranjit Hoskote

HERNING MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART Ranjit Hoskote: Signposting the Indian Highway Ranjit Hoskote You Can’t Drive Down the Same Highway Twice… …as Ed Ruscha might have said to Heraclitus. But to begin this story properly: two artists, two highways, two time horizons a decade apart in India. Atul Dodiya’s memorable painting, ‘Highway: For Mansur’, was first shown at his 1999Vadehra Art Gallery solo exhibition in New Delhi. The painting is dominated by a pair of vultures, a quotation culled from the folios of the Mughal artist Mansur; the birds look down on a highway that cuts diagonally across a desert. The decisiveness of this symbol of progress is negated by a broken-down car that stands right in the middle of it. The sun beats down on the marooned driver, whose ineffectual attempts at repairing his vehicle are viewed with interest by the predators. In the lower half of the frame, Dodiya inserts an enclosure in which a painter, identifiably the irrepressible satirist and gay artist Bhupen Khakhar, bends over his work. Veined with melancholia as well as quixotic humour, this painting prompts several interpretations. Does the car symbolise the fate of painting as an artistic choice, at a time when new media possibilities were opening up; is the car shorthand for the project of modernism? Or is this an elegy for the beat-up postcolonial nation-state, becalmed in the dunes of globalisation? In an admittedly summary reading, ‘Highway: For Mansur’ could be viewed as an allegory embodying a dilemma that has immobilised the artist, even as he contemplates flamboyant encounters with history in the confines of his studio. -

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures 123 Editors Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape California Institute of Integral Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University San Francisco, CA New Delhi USA India ISBN 978-81-322-3635-1 ISBN 978-81-322-3637-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947189 © Springer India 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer (India) Pvt. -

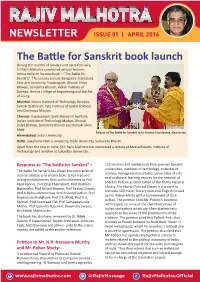

The Battle for Sanskrit Book Launch

NEWSLETTER ISSUE 01 | APRIL 2016 The Battle for Sanskrit book launch During the months of January and early February, Sri Rajiv Malhotra conducted various lectures across India on his new book – “The Battle for Sanskrit”. The venues include Bangalore: Karnataka Samskrit University, Yuvabrigade, Bharati Vidya Bhavan, Samskrita Bharati, Indian Institute of Science, Amrita College of Engineering and the Art of Living. Mumbai: Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Samskrita Bharati, Tata Institute of Social Sciences and Chinmaya Mission. Chennai: Kuppuswami Sastri Research Institute, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Bharati Vidya Bhavan, Samskrita Bharati and Ramakrishna Mutt. Release of The Battle for Sanskrit at Sri Krishna Vrundavana, New Jersey Ahmedabad: Indus University. Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi University, Samskrita Bharati. Apart from the tour in India, Shri Rajiv Malhotra has conducted a lecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and another at Columbia University. Response to “The Battle for Sanskrit”:- 132 scholars and intellectuals from premier Sanskrit universities, institutes of technology, institutes of The Battle for Sanskrit has drawn the admiration of science, management institutes, universities of arts several scholars and intellectuals. It has received and traditional learning centres for the removal of strong endorsements from such luminaries as Prof Sheldon Pollock as Chief Editor of the Murty Classical Kapil Kapoor, Prof Dilip Chakrabarti, Prof Roddam Library. The Murty Classical Library is a project to Narasimha, Prof Arvind Sharma, Prof Pankaj Chande, translate 500 Indian literary texts into English funded Prof K Ramasubramanian, Prof R Vaidyanathan, Prof by Mr. Rohan Murty with a commitment of $5.6 Dayananda Bharghava, Prof S.R. Bhatt, Prof K.S. -

The Case for Sanskrit As India's National Language by Makarand

The Case for Sanskrit as India’s National Language By Makarand Paranjape August 2012 This paper discusses in depth the role and the potential of Sanskrit in India’s cultural and national landscape. Reproduced with the author’s permission, it has been published in Sanskrit and Other Indian Languages , ed. Shashiprabha Kumar (New Delhi: D. K. Printworld, 2007), pp. 173- 200. “Sanskrit is the thread on which the pearls of the necklace of Indian culture are strung; break the thread and all the pearls will be scattered, even lost forever.” Dr. Lokesh Chandra Introduction I had first heard from my friends in the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry, that the Mother wanted Sanskrit to be made the national language of India. Indeed, Sanskrit is taught from childhood not only in the ashram schools, but also at Auroville, the comm unity that the Mother founded. On 11th November 1967, the Mother said: “ Sanskrit! Everyone should learn that. Especially everyone who works here should learn that….” 1 Because some degree of confusion persisted over the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s views on the topic, a more direct question was put to the former on 4 October 1971: On certain issues where You and Sri Aurobindo have given direct answers, we [Sri Aurobindo's Action] are also specific, as for instance... on the language issue where You have said for the country that (1) the regional language should be the medium of instruction, (2) Sanskrit should be the national language, and (3) English should be the international language. Are we correct in giving these replies to such questions? Yes. -

Towards an Alternative Indian Poetry Akshaya K. Rath

Towards an Alternative Indian Poetry Akshaya K. Rath One of the debates that has kept literary scholars of the present generation engaged and has ample implication for teaching pedagogy is the problem of canon-formation in Indian English poetry. One of the ways in which such canon- making operates is through the compilation, use and importance of anthologies. Anthology making is a conscious political act that sanctions a poet or poem its literary status. It has given rise to the publication of numerous anthologies in the Indian scenario and in the recent decades we have witnessed the emergence of a handful of alternative anthologies. Anthologies in general remain compact; they are convenient and often less expensive than purchasing separate texts. Those are some of the reasons for their popularity. However, as the case has been, inclusion of a poet or poem is hardly an innocent phenomenon. We have witnessed that canonical anthologies in India are exclusive about their selection of poets and poems, and in most cases the editor‘s profession remains central to anthology making. Hence, there is a need to address the issue of anthology making in Indian scenario that decides the future of poetry/poets in India. This paper explores the historiography of anthology making in India in the light of the great Indian language debate put forward by Buddhadeva Bose. It also highlights that there a significant transition in the subject of canon-formation at the turn of the century with the rise of an alternative canon. The politics of inclusion and exclusion—of anthologizing and publishing Indian English poetry—will be central to the discussion of anthologizing alternative Indian English poetry. -

EIIRJ) ISSN 2277- 8721 Bi-Monthly Reviewed Journal Mar/April 2013

Electronic International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (EIIRJ) ISSN 2277- 8721 Bi-monthly Reviewed Journal Mar/April 2013 MYSTICISM IN THE POETRY OF LAL DED (LALLESHWARI) Dr. Shashikant Mhalunkar P.G. Dept. of English, B. N. N. College, Bhiwandi, Dist. Thane (Maharashtra) ABSTRACT: India has a long tradition of saints, poets, devotees, mystics and religious traditions and the changing patterns of devotion from time to time and from sect to sect. The hybridity in cultures, languages and religions in India has produced abundant material in the course of time that has been attracting scholars all over the world. Man has been worshipping god, nature or virtues. Mysticism is a record of man’s worship of god, almighty or the nature. History is evident that man has been taking refuge of religion to express his mysticism. Similarly, women who could not express their discontent against the parochial codes openly embraced mysticism. Religion provides them the courage to attack the pompous patriarchal and religious practices, as well as the solace and escape from the tyranny of the cryptograph of man dominated society. This paper attempts to explore the mysticism in the poetry of Lal Ded, the fourteenth century Kashmiri female poet. Her poetry is a confluence of Saivism and Sufism. The religious ecstasy in her Vakhs exhibits the mysticism that is captured by a female poet of the fourteenth century wherein the impact of Muslim intrusion was very strong in the valley. Her poetry not only celebrates the power of the Almighty but also attack inhuman treatment that she gets from the contemporary society due to her religious conviction. -

Professor Makarand Paranjape Currently Holds the ICCR Chair in Indian Studies, South Asian Studies Programme, National University of Singapore

The Center for the Study of Hindu Traditions, University of Florida presents The Relevance of Gandhi to Environmental Studies by Professor Makarand Paranjape Professor Makarand Paranjape currently holds the ICCR Chair in Indian Studies, South Asian Studies Programme, National University of Singapore. He is also Professor of English, Centre for English Studies, School of Language, Literature, and Culture Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He received his M.A. and Ph.D. in English from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Professor Paranjape has held a number of fellowships in several universities; he was previously the Homi Bhabha Fellow for Literature in India; Shastri Indo-Candian Research Fellow, University of Calgary; IFUSS Fellow, University of Iowa; Mellon Fellow, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; and Shivdasani Visiting Fellow, Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, University of Oxford. He has also been a Visiting Professor at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona and the Universitat des Sarlandes. Professor Paranjape will also be leading a class discussion on Hindu Traditions in Singapore (April 11, 2:30 pm, Room 117, Anderson Hall) Professor Paranjape is the author or editor of several books including Decolonization and Development: Hind Svaraj Revisioned (1993); Nativism: Essays in Literary Criticism (Sahitya Akademi, 1997); In Diaspora: Theories, Histories, Texts, Editor (2001); Sacred Australia: post-secular considerations (2009); Altered Destinations: Self, Society, and Nation in India (Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 2010); Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production (Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 2010); as well as the author of several volumes of poetry and fiction.. -

RAVI AGARWAL B

RAVI AGARWAL b. 1958, New Delhi Lives and works in New Delhi Founder of Toxics Link, 1997 EDUCATION Self-taught artist, environmental activist, writer and curator SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Ecologies of Loss, Curated Marco Stoconi, PAV Centre, Turin The Desert of the Anthropocene, India Art Fair – Solo Project Booth 2018 Nadir/Prakriti, Edinburgh Printmakers Galleries, Edinburgh Art Festival Can you hear the Sea Speak, Public Art Installation, Auroville 50th Anniversary 2017 The Familiar is Always a Stanger, Two person show with Francois Delecroix, IFI and Gallery Espace 2016 Else, all will be still, Gallery Espace, New Delhi 2015 Else, all will be still, The Guild, Alibaug, Mumbai 2011 Of Value and Labour, The Guild, Mumbai 2010-11 Flux: dystopia, utopia, heterotopias, Gallery Espace, New Delhi 2008 An Other Place, Gallery Espace, New Delhi 2006 Alien Waters, India International Centre, New Delhi 2000 Down and Out, Labouring under Global Capitalism, India Habitat Centre, New Delhi; The Hutheesingh Visual Arts Gallery, Ahmedabad; National Vakbondsmuseum, Amsterdam 1995 A Street View, All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society, New Delhi SELECTED MUSEUM / INSTITUTIONAL EXHIBITIONS 2019 Human>Rupture<> XIII Havana Biennial, April 2019, Cuba 2018 Room of Sands and Room of the Seas, in Ecologies on the Edge, Starting from the Desert, Yinchuan Biennial, curated Curated Marco Scotini, Museum of Contemporary Art, Yinchuan, China 2017 Anti-Memoirs, Curated Ranjit Hoskote, Serendipity Arts Festival, Goa 50:50, Curated Johny M.L., Birla Academy of the Arts, -

Raja Rao and the Politics of Truth

Lingue e Linguaggi Lingue Linguaggi 13 (2015), 227- ISSN 2239-0367, e-ISSN 2239-0359 DOI 10.1285/i22390359v13p227 http://siba-ese.unisalento.it, © 2015 Università del Salento FROM INDIANNESS TO HUMANNESS: RAJA RAO AND THE POLITICS OF TRUTH STEFANO MERCANTI UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI UDINE Abstract – Raja Rao is not merely a metaphysical writer, as many scholars of the first Commonwealth generation depict him as being, but rather a much more complex one whose literary dimensions transcend the commonplace essentializing ‘Hinduness’ projected by many critics over three decades. I thus suggest instead an amplification of Rao’s idea of India by framing his novels in a cross-cultural space which evolves during the course of his entire oeuvre on both philosophical and political levels. This dynamic ambivalence has its foremost predecessor in Mahatma Gandhi’s politico-spiritual legacy, Satyagraha (‘the force of Truth’) which becomes the centripetal and cohesive force of Raja Rao’s fiction. Keywords: Indianness; partnership model; Mahatma Gandhi; Indian English literature. Raja Rao is known to have given birth to the Indian English novel as an expression of a precise ideological re-construction of India’s racial, philosophical, cultural and linguistic specificities. His work asserted itself on the inter-national scene, and especially in a trans- national way, due to the originality of an idea of India capable of communicating with the West even through images and life styles distinctively indigenous. However, because of this extraordinary celebration of India’s native cultural distinctiveness, Raja Rao has been often ossified within the cultural construct of a universalistic Indian identity, an Indianness quintessentially and metaphysically Hindu, thus blurring the complexities and making exotic Indian geography and culture. -

Textframe: Cosmopolitanism and Non-Exclusively Anglophone Poetries

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 TextFrame: Cosmopolitanism and Non-Exclusively Anglophone Poetries Michael N. Scharf The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3447 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] TextFrame: Cosmopolitanism and Non-Exclusively Anglophone Poetries by Michael Scharf A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 MICHAEL SCHARF, 2019 Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) ii TextFrame: Cosmopolitanism and Non-Exclusively Anglophone Poetries by Michael Scharf This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________ _________________________________________ Date Ammiel Alcalay Chair of Examining Committee ______________________ _________________________________________ Date Kandice Chuh Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: _________________________________________ Ammiel Alcalay __________________________________________ Matthew K. Gold __________________________________________