Transgender People and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum Andrew S. Forshee, Ph.D., Early Education & Family Studies Portland Community College Portland, Oregon INTRODUCTION Homophobia and transphobia are complicated topics that touch on core identity issues. Most people tend to conflate sexual orientation with gender identity, thus confusing two social distinctions. Understanding the differences between these concepts provides an opportunity to build personal knowledge, enhance skills in allyship, and effect positive social change. GROUND RULES (1015 minutes) Materials: chart paper, markers, tape. Due to the nature of the topic area, it is essential to develop ground rules for each student to follow. Ask students to offer some rules for participation in the postperformance workshop (i.e., what would help them participate to their fullest). Attempt to obtain a group consensus before adopting them as the official “social contract” of the group. Useful guidelines include the following (Bonner Curriculum, 2009; Hardiman, Jackson, & Griffin, 2007): Respect each viewpoint, opinion, and experience. Use “I” statements – avoid speaking in generalities. The conversations in the class are confidential (do not share information outside of class). Set own boundaries for sharing. Share air time. Listen respectfully. No blaming or scapegoating. Focus on own learning. Reference to PCC Student Rights and Responsibilities: http://www.pcc.edu/about/policy/studentrights/studentrights.pdf DEFINING THE CONCEPTS (see Appendix A for specific exercise) An active “toolkit” of terminology helps support the ongoing dialogue, questioning, and understanding about issues of homophobia and transphobia. Clear definitions also provide a context and platform for discussion. Homophobia: a psychological term originally developed by Weinberg (1973) to define an irrational hatred, anxiety, and or fear of homosexuality. -

Why Allowing Sex-Reassignment Surgery for Transgender Life Prisoners Facilitates Rehabilitation and Reconciliation

THE CAGED BIRD SINGS OF FREEDOM: WHY ALLOWING SEX-REASSIGNMENT SURGERY FOR TRANSGENDER LIFE PRISONERS FACILITATES REHABILITATION AND RECONCILIATION BY: ALEXANDER KIRKPATRICK* ABSTRACT In October 2015, California became the first state in U.S. history to implement guidelines for transgender state prisoners to petition for gender- affirming and sex-reassignment surgeries. These guidelines raise the question why California would authorize gender-affirming surgeries for prisoners serving life-sentences, yet struggle to implement laws to make the same surgeries more accessible to law-abiding citizens. While the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation ("CDCR") likely implemented the radical SRS policy to abide by Eighth Amendment protections for transgender inmates suffering from severe gender dysphoria-inmates to whom SRS coverage is medically necessary and constitutionally required-this Note outlines four alternative justifications * Class of 2017, University of Southern California Gould School of Law, B.A. Political Science, University of Colorado at Boulder. This Note is dedicated to my client, Amelia, who shared her vulnerable and inspiring story of incarceration, transition, and hope. Amelia is fighting for freedom every day in a California male institution. Thank you to my mentor and Note supervisor, Heidi Rummel, whom champions juvenile justice at the Post-Conviction Justice Project. She has exemplified the values of a lawyer I hope to become. Dear thanks to my partner, Mifa, who continues to challenge me to approach the world with empathy and fight for social justice. Thank you to my parents, brother, and aunt who have supported me every step of the way and showed me the value of storytelling. -

Name Change Checklist

Name Change Checklist Government Agencies Social Security Administration Department of Motor Vehicles - driver's license, car title and registration Voter Registration US Passport Post Office, if change of address Military or Veteran Records Public Assistance Naturalization Papers Any open court orders Work and Employment W-4 Form 401k Health Insurance Benefits (including Beneficiaries) Email ID Card Business Cards Name Plate Work website / website contact information Unions Professional Organizations Professional Licenses Personal website – if you have a resume based website Banks / Financial Institutions Checking accounts, checks, and bank cards Savings and money market accounts, CDs Credit Cards Assets such as property titles, deeds, trusts Debts such as mortgages and personal loans Debts such as auto or school loans Investment accounts, including IRAs, and 401ks Insurance Policies such as life, disability Home Homeowners or renters insurance Landlord Home owners association or management agency Property Tax department / Tax assessor Utilities o Electric o Gas o Water / sewer o Telephones (including cell and landline) o Internet o Cable Auto Insurance Medical Doctor Dentist Ob-Gyn Therapists Counselors Eye Doctor Pharmacy Veterinarian / Micro Chip Company Personal School / School Records / Alumni Associations Groups, Associations, Organizations Subscriptions Airline Miles Programs Loyalty Clubs Road Toll Accounts Your Voicemail Gym Membership Church / Religious Organizations Other Legal Documents Health proxy Power of Attorney Will Living Trusts Your Attorney Social Media Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Flickr Instagram Personal Blog or Website Email Accounts Brought to you by http://www.littlethingsfavors.com . -

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents Of

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents of Greater Capital Region, New York By, Lettie Dickerson, Esq., Milo Primeaux, Esq., Kevin M. Nelson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................................ 3 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1: CHANGING YOUR NAME IN COURT ............................................................................ 6 STEP BY STEP OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 6 PREPARING THE PETITION ............................................................................................................................ 8 ABOUT NAME CHANGE PUBLICATION REQUIREMENT ................................................................................... 9 NAME CHANGE APPLICATION CHECKLIST ...................................................................................................10 SECTION 2: UPDATING ID .....................................................................................................................11 SOCIAL SECURITY .......................................................................................................................................11 -

PRELIMINARY STAFF REPORT To: City Planning Commission Prepared By: Nicolette Jones, Stosh Kozlowski, Laura Baños, and Derreck Deason Date: February 16, 2015

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CITY OF NEW ORLEANS MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU ROBERT D. RIVERS MAYOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR LESLIE T. ALLEY DEPUTY DIRECTOR City Planning Commission Staff Report Executive Summary Consideration: Request by City Council Motion M-15-444 for the City Planning Commission to conduct a study and public hearing to amend its Administrative Rules, Policies, & Procedures relative to the creation of an honorary street name change process. Background: To date, the City of New Orleans does not have a policy related to an honorary street dedication program. Currently, the City’s street naming policy, which is documented in the City Planning Commission’s Administrative Rules, Policies, and Procedures, only delineates the procedure for street name changes. An honorary street dedication program, which many other jurisdictions across the country have implemented, allows cities the opportunity to commemorate individuals and groups who have made significant contributions to the community, but without causing any disruption of the existing street grid associated with a modification to the Official Map as would a permanent street name change. According to best practices, honorary street signage is typically a secondary sign that is installed above or below an existing street name sign. The City Council has granted honorary street dedications in the recent past, though without a formalized policy to guide the process. Following the recent approval of street name changes in the spring of 2015, the New Orleans City Council requested that the City Planning Commission review the City’s street renaming rules and explore opportunities to create an honorary street dedication program. Recommendation: In order to promote clear wayfinding, efficient emergency response and service delivery, as well as accurate address keeping, the staff advises against frequent changes to the City’s Official Map. -

Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services

The University of the State of New York The State Education Department Office of the Professions Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services www.op.nysed.gov DO NOT USE THIS FORM IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY. IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY, YOU MUST SUBMIT A CONTACT US FORM ON THE OFFICE OF THE PROFESSIONS' WEBSITE AT https://eservices.nysed.gov/professions/contact-us/#/ Instructions: Use this form to report a change in your name. Read these instructions carefully and complete all applicable sections of this form. Be sure to print clearly in ink. You must include acceptable supporting documentation. Acceptable supporting documentation includes: A photocopy of a court, marriage certificate, or divorce papers authorizing your name change and a photocopy of a photo ID in your new name. Or Two (2) of the following sets of supporting documents: ● A letter from the Social Security Administration indicating both your old and new names. ● Copies of both old and new driver's licenses. ● Copies of both old and new New York State non-driver photo ID cards. ● Copies of both old and new Social Security Cards. ● Copies of both old and new passports. ● Copies of both old and new U.S. Military photo ID cards. Other forms of identification may be acceptable as supporting documentation. Please contact the Records and Archives Unit by calling 518-474-3817 Extension 380 or by emailing [email protected] before submitting. Currently registered licensed professionals will be sent a new registration certificate. Also, if you would like to replace your existing license parchment with one in your new name, check the appropriate box in Section II and enclose your original parchment (your original parchment will be letter sized, 8.5 x 11 inches, and will not have your address on it). -

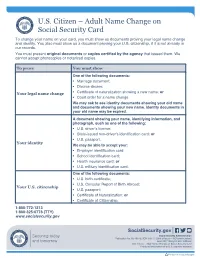

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

The Role of the United Nations in Combatting Discrimination and Violence Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People

The Role of the United Nations in Combatting Discrimination and Violence against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People A Programmatic Overview 19 June 2018 This paper provides a snapshot of the work of a number of United Nations entities in combatting discrimination and violence based on sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics and related work in support of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) and intersex communities around the world. It has been prepared by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on the basis of inputs provided by relevant UN entities, and is not intended to be either exhaustive or detailed. Given the evolving nature of UN work in this field, it is likely to benefit from regular updating1. The final section, below, includes a Contact List of focal points in each UN entity, as well as links and references to documents, reports and other materials that can be consulted for further information. Click to jump to: Joint UN statement, OHCHR, UNDP, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO, the World Bank, IOM, UNAIDS (the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS), UNRISD and Joint UN initiatives. Joint UN statement Joint UN statement on Ending violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people: o On 29 September 2015, 12 UN entities (ILO, OHCHR, UNAIDS Secretariat, UNDP, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNODC, UN Women, WFP and WHO) released an unprecedented joint statement calling for an end to violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people. o The statement is a powerful call to action to States and other stakeholders to do more to protect individuals from violence, torture and ill-treatment, repeal discriminatory laws and protect individuals from discrimination, and an expression of the commitment on the part of UN entities to support Member States to do so. -

Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12695 Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction Nick Drydakis OCTOBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12695 Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction Nick Drydakis Anglia Ruskin University, University of Cambridge and IZA OCTOBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 12695 OCTOBER 2019 ABSTRACT Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction For trans people (i.e. people whose gender is not the same as the sex they were assigned at birth) evidence suggests that transitioning (i.e. -

Names and “Doing Gender”: How Forenames and Surnames

Sex Roles DOI 10.1007/s11199-017-0805-4 FEMINIST FORUM REVIEW ARTICLE Names and BDoing Gender^: How Forenames and Surnames Contribute to Gender Identities, Difference, and Inequalities Jane Pilcher1 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Names, as proper nouns, are clearly important for Nonetheless, practices of personal naming in these countries the identification of individuals in everyday life. In the present are patterned and structured: first, as a consequence of repli- article, I argue that forenames and surnames need also to be cation of usage of the names of individuals and recurring recognized as Bdoing^ words, important in the categorization demands for the authentication of individual identity over of sex at birth and in the ongoing management of gender time; second, by cultural traditions and conventions (including conduct appropriate to sex category. Using evidence on per- those patrilineal and patriarchal in origin) whereby personal sonal naming practices in the United States and United names are used to mark individual and social identities (Finch Kingdom, I examine what happens at crisis points of sexed 2008). Despite their fundamental and ubiquitous importance and gendered naming in the life course (for example, at the for each individual in a multitude of contexts, scholars are birth of babies, at marriage, and during gender-identity transi- only just beginning to give personal names and naming prac- tions). I show how forenames and surnames help in the em- tices Bthe theoretical and analytical scrutiny^ they deserve bodied doing of gender and, likewise, that bodies are key to (Palsson 2014,p.618). -

Media Reference Guide

media reference guide NINTH EDITION | AUGUST 2014 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 1 GLAAD MEDIA CONTACTS National & Local News Media Sports Media [email protected] [email protected] Entertainment Media Religious Media [email protected] [email protected] Spanish-Language Media GLAAD Spokesperson Inquiries [email protected] [email protected] Transgender Media [email protected] glaad.org/mrg 2 / GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION FAIR, ACCURATE & INCLUSIVE 4 GLOSSARY OF TERMS / LANGUAGE LESBIAN / GAY / BISEXUAL 5 TERMS TO AVOID 9 TRANSGENDER 12 AP & NEW YORK TIMES STYLE 21 IN FOCUS COVERING THE BISEXUAL COMMUNITY 25 COVERING THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY 27 MARRIAGE 32 LGBT PARENTING 36 RELIGION & FAITH 40 HATE CRIMES 42 COVERING CRIMES WHEN THE ACCUSED IS LGBT 45 HIV, AIDS & THE LGBT COMMUNITY 47 “EX-GAYS” & “CONVERSION THERAPY” 46 LGBT PEOPLE IN SPORTS 51 DIRECTORY OF COMMUNITY RESOURCES 54 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 3 INTRODUCTION Fair, Accurate & Inclusive Fair, accurate and inclusive news media coverage has played an important role in expanding public awareness and understanding of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) lives. However, many reporters, editors and producers continue to face challenges covering these issues in a complex, often rhetorically charged, climate. Media coverage of LGBT people has become increasingly multi-dimensional, reflecting both the diversity of our community and the growing visibility of our families and our relationships. As a result, reporting that remains mired in simplistic, predictable “pro-gay”/”anti-gay” dualisms does a disservice to readers seeking information on the diversity of opinion and experience within our community. Misinformation and misconceptions about our lives can be corrected when journalists diligently research the facts and expose the myths (such as pernicious claims that gay people are more likely to sexually abuse children) that often are used against us.