The Cardiomyocyte Cell Cycle," Novartis Found Symposium 274 (2006): 196-276

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expression Profiling of KLF4

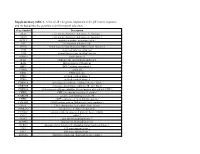

Expression Profiling of KLF4 AJCR0000006 Supplemental Data Figure S1. Snapshot of enriched gene sets identified by GSEA in Klf4-null MEFs. Figure S2. Snapshot of enriched gene sets identified by GSEA in wild type MEFs. 98 Am J Cancer Res 2011;1(1):85-97 Table S1: Functional Annotation Clustering of Genes Up-Regulated in Klf4 -Null MEFs ILLUMINA_ID Gene Symbol Gene Name (Description) P -value Fold-Change Cell Cycle 8.00E-03 ILMN_1217331 Mcm6 MINICHROMOSOME MAINTENANCE DEFICIENT 6 40.36 ILMN_2723931 E2f6 E2F TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR 6 26.8 ILMN_2724570 Mapk12 MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 12 22.19 ILMN_1218470 Cdk2 CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE 2 9.32 ILMN_1234909 Tipin TIMELESS INTERACTING PROTEIN 5.3 ILMN_1212692 Mapk13 SAPK/ERK/KINASE 4 4.96 ILMN_2666690 Cul7 CULLIN 7 2.23 ILMN_2681776 Mapk6 MITOGEN ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 4 2.11 ILMN_2652909 Ddit3 DNA-DAMAGE INDUCIBLE TRANSCRIPT 3 2.07 ILMN_2742152 Gadd45a GROWTH ARREST AND DNA-DAMAGE-INDUCIBLE 45 ALPHA 1.92 ILMN_1212787 Pttg1 PITUITARY TUMOR-TRANSFORMING 1 1.8 ILMN_1216721 Cdk5 CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE 5 1.78 ILMN_1227009 Gas2l1 GROWTH ARREST-SPECIFIC 2 LIKE 1 1.74 ILMN_2663009 Rassf5 RAS ASSOCIATION (RALGDS/AF-6) DOMAIN FAMILY 5 1.64 ILMN_1220454 Anapc13 ANAPHASE PROMOTING COMPLEX SUBUNIT 13 1.61 ILMN_1216213 Incenp INNER CENTROMERE PROTEIN 1.56 ILMN_1256301 Rcc2 REGULATOR OF CHROMOSOME CONDENSATION 2 1.53 Extracellular Matrix 5.80E-06 ILMN_2735184 Col18a1 PROCOLLAGEN, TYPE XVIII, ALPHA 1 51.5 ILMN_1223997 Crtap CARTILAGE ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 32.74 ILMN_2753809 Mmp3 MATRIX METALLOPEPTIDASE -

Supplemental Table S1 (A): Microarray Datasets Characteristics

Supplemental table S1 (A): Microarray datasets characteristics Title Summary Samples Literature ref. GEO ref. Acquisition of granule Gene expression profiling of 27 (1) GSE 11859 neuron precursor identity cerebellar tumors generated and Hedgehog‐induced from various early and late medulloblastoma in mice. stage CNS progenitor cells Medulloblastomas derived Study of mouse 5 (2) GSE 7212 from Cxcr6 mutant mice medulloblastoma in response respond to treatment with to inhibitor of Smoothened a Smoothened inhibitor Expression profiles of Identification of distinct classes 10 (3) GSE 9299 mouse medulloblastoma of up‐regulated or down‐ 339 & 340 regulated genes during Hh dependent tumorigenesis Genetic alterations in Identification of differently 10 (4) GSE 6463 mouse medulloblastomas expressed genes among CGNPs 339 & and generation of tumors and CGNPs transfected with 340 from cerebellar granule retroviruses that express nmyc neuron precursors or cyclin‐d1 Patched heterozygous Analysis of granule cell 14 (5) GSE 2426 model of medulloblastoma precursors, pre‐neoplastic cells, GDS1110 and tumor cells 1. Schuller U, Heine VM, Mao J, Kho AT, Dillon AK, Han YG, et al. Acquisition of granule neuron precursor identity is a critical determinant of progenitor cell competence to form Shh‐induced medulloblastoma. Cancer Cell 2008;14:123‐134. 2. Sasai K, Romer JT, Kimura H, Eberhart DE, Rice DS, Curran T. Medulloblastomas derived from Cxcr6 mutant mice respond to treatment with a smoothened inhibitor. Cancer Res 2007;67:3871‐3877. 3. Mao J, Ligon KL, Rakhlin EY, Thayer SP, Bronson RT, Rowitch D, et al. A novel somatic mouse model to survey tumorigenic potential applied to the Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Res 2006;66:10171‐10178. -

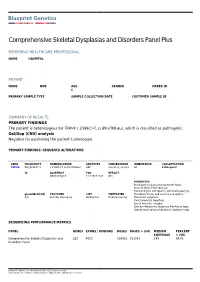

Report 99517

Comprehensive Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders Panel Plus REFERRING HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL NAME HOSPITAL PATIENT NAME DOB AGE GENDER ORDER ID 6 PRIMARY SAMPLE TYPE SAMPLE COLLECTION DATE CUSTOMER SAMPLE ID SUMMARY OF RESULTS PRIMARY FINDINGS The patient is heterozygous for TRPV4 c.2396C>T, p.(Pro799Leu), which is classified as pathogenic. Del/Dup (CNV) analysis Negative for explaining the patient’s phenotype. PRIMARY FINDINGS: SEQUENCE ALTERATIONS GENE TRANSCRIPT NOMENCLATURE GENOTYPE CONSEQUENCE INHERITANCE CLASSIFICATION TRPV4 NM_021625.4 c.2396C>T, p.(Pro799Leu) HET missense_variant AD Pathogenic ID ASSEMBLY POS REF/ALT GRCh37/hg19 12:110222183 G/A PHENOTYPE Brachyolmia (autosomal dominant type), Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Familial Digital arthropathy with brachydactyly, gnomAD AC/AN POLYPHEN SIFT MUTTASTER Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy, 0/0 possibly damaging deleterious disease causing Metatropic dysplasia, Parastremmatic dwarfism, Spinal muscular atrophy, Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia Maroteaux type, Spondylometaphyseal dysplasia Kozlowski type SEQUENCING PERFORMANCE METRICS PANEL GENES EXONS / REGIONS BASES BASES > 20X MEDIAN PERCENT COVERAGE > 20X Comprehensive Skeletal Dysplasias and 252 4053 816901 812241 199 99.43 Disorders Panel Blueprint Genetics Oy, Keilaranta 16 A-B, 02150 Espoo, Finland VAT number: FI22307900, CLIA ID Number: 99D2092375, CAP Number: 9257331 TARGET REGION AND GENE LIST The Blueprint Genetics Comprehensive Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders Panel (version 4, Oct 19, 2019) Plus Analysis includes sequence -

Cytoplasmic Localized Ubiquitin Ligase Cullin 7 Binds to P53 and Promotes Cell Growth by Antagonizing P53 Function

Oncogene (2006) 25, 4534–4548 & 2006 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/06 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Cytoplasmic localized ubiquitin ligase cullin 7 binds to p53 and promotes cell growth by antagonizing p53 function P Andrews1,2,YJHe1 and Y Xiong1,2,3 1Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; 2Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA and 3Program in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA Cullins are a family of evolutionarily conserved proteins monomeric manner (monoubiquitination) to cause that bind to the small RING fingerprotein,ROC1, to conformational change to the substrate or in a constitute potentially a large number of distinct E3 polyubiquitin chain which signals the substrate to be ubiquitin ligases. CUL7 mediates an essential function degraded by the 26S proteasome. Both ubiquitin formouse embryodevelopment and has been linked with activating and conjugating enzymes are well character- cell transformation by its physical association with the ized and contain highly conserved functional domains. SV40 large T antigen. We report here that, like its closely The identity and mechanism of E3 ubiquitin ligases, on related homolog PARC, CUL7 is localized predominantly the other hand, has been elusive and long postulated as in the cytoplasm and binds directly to p53. In contrast to an activity responsible for both recognizing substrates PARC, however, CUL7, even when overexpressed, did not and for catalysing polyubiquitin chain formation sequesterp53 in the cytoplasm. We have identified a (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998). sequence in the N-terminal region of CUL7 that is highly Currently, two major families of E3 ligases have been conserved in PARC and a sequence spanning the described. -

Cullin 7 in Tumor Development: a Novel Potential Anti-Cancer Target

572 Neoplasma 2021; 68(3): 572–579 doi:10.4149/neo_2021_201207N1324 Cullin 7 in tumor development: a novel potential anti-cancer target Yumiao LI1,#, Aiming ZANG1,#, Jiejun FU2, Youchao JIA1,* 1Department of Medical Oncology, Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Hebei Key Laboratory of Cancer Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy, Baoding, Hebei, China; 2Department of Cell Biology and Genetics, Guangxi Medical University, Key Laboratory of Longevity and Aging-related Diseases of Chinese Ministry of Education, Center for Translational Medicine and School of Preclinical Medicine, Nanning, Guangxi, China *Correspondence: [email protected] #Contributed equally to this work. Received December 7, 2020 / Accepted January 25, 2021 As a core scaffold protein, Cullin 7 (Cul7) forms Skp1-Cullin-F-box (SCF) E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes with the regulator of cullins-1 (ROC1), S-phase kinase associated protein 1 (Skp1) and F-Box, and WD repeat domain containing 8 (Fbxw8). Alternatively, Cul7 can form a CRL7SMU1 complex with suppressor of Mec-8 and Unc-52 protein homolog (SMU1), damage-specific DNA binding protein 1 (DDB1), and ring finger protein 40 (RNF40), to promote cell growth. The mutations of Cul7 cause the 3-M dwarf syndrome, indicating Cul7 plays an important role in growth and development in humans and mice. Moreover, Cul7 regulates cell transformation, tumor protein p53 activity, cell senescence, and apoptosis, mutations in Cul7 are also involved in the development of tumors, indicating the characteristics of an oncogene. Cul7 is highly expressed in breast cancer, lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, and other malignant tumors where Cul7 promotes tumor development, cell transformation, and cell survival by regulating complex signaling pathways associated with protein degradation. -

Clinical, Molecular, and Immune Analysis of Dabrafenib-Trametinib

Supplementary Online Content Chen G, McQuade JL, Panka DJ, et al. Clinical, molecular and immune analysis of dabrafenib-trametinib combination treatment for metastatic melanoma that progressed during BRAF inhibitor monotherapy: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncology. Published online April 28, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0509. eMethods. eReferences. eTable 1. Clinical efficacy eTable 2. Adverse events eTable 3. Correlation of baseline patient characteristics with treatment outcomes eTable 4. Patient responses and baseline IHC results eFigure 1. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival eFigure 2. Correlation between IHC and RNAseq results eFigure 3. pPRAS40 expression and PFS eFigure 4. Baseline and treatment-induced changes in immune infiltrates eFigure 5. PD-L1 expression eTable 5. Nonsynonymous mutations detected by WES in baseline tumors This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/30/2021 eMethods Whole exome sequencing Whole exome capture libraries for both tumor and normal samples were constructed using 100ng genomic DNA input and following the protocol as described by Fisher et al.,3 with the following adapter modification: Illumina paired end adapters were replaced with palindromic forked adapters with unique 8 base index sequences embedded within the adapter. In-solution hybrid selection was performed using the Illumina Rapid Capture Exome enrichment kit with 38Mb target territory (29Mb baited). The targeted region includes 98.3% of the intervals in the Refseq exome database. Dual-indexed libraries were pooled into groups of up to 96 samples prior to hybridization. -

Perkinelmer Genomics to Request the Saliva Swab Collection Kit for Patients That Cannot Provide a Blood Sample As Whole Blood Is the Preferred Sample

Autism and Intellectual Disability TRIO Panel Test Code TR002 Test Summary This test analyzes 2429 genes that have been associated with Autism and Intellectual Disability and/or disorders associated with Autism and Intellectual Disability with the analysis being performed as a TRIO Turn-Around-Time (TAT)* 3 - 5 weeks Acceptable Sample Types Whole Blood (EDTA) (Preferred sample type) DNA, Isolated Dried Blood Spots Saliva Acceptable Billing Types Self (patient) Payment Institutional Billing Commercial Insurance Indications for Testing Comprehensive test for patients with intellectual disability or global developmental delays (Moeschler et al 2014 PMID: 25157020). Comprehensive test for individuals with multiple congenital anomalies (Miller et al. 2010 PMID 20466091). Patients with autism/autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Suspected autosomal recessive condition due to close familial relations Previously negative karyotyping and/or chromosomal microarray results. Test Description This panel analyzes 2429 genes that have been associated with Autism and ID and/or disorders associated with Autism and ID. Both sequencing and deletion/duplication (CNV) analysis will be performed on the coding regions of all genes included (unless otherwise marked). All analysis is performed utilizing Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology. CNV analysis is designed to detect the majority of deletions and duplications of three exons or greater in size. Smaller CNV events may also be detected and reported, but additional follow-up testing is recommended if a smaller CNV is suspected. All variants are classified according to ACMG guidelines. Condition Description Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) refers to a group of developmental disabilities that are typically associated with challenges of varying severity in the areas of social interaction, communication, and repetitive/restricted behaviors. -

Oxidized Phospholipids Regulate Amino Acid Metabolism Through MTHFD2 to Facilitate Nucleotide Release in Endothelial Cells

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04602-0 OPEN Oxidized phospholipids regulate amino acid metabolism through MTHFD2 to facilitate nucleotide release in endothelial cells Juliane Hitzel1,2, Eunjee Lee3,4, Yi Zhang 3,5,Sofia Iris Bibli2,6, Xiaogang Li7, Sven Zukunft 2,6, Beatrice Pflüger1,2, Jiong Hu2,6, Christoph Schürmann1,2, Andrea Estefania Vasconez1,2, James A. Oo1,2, Adelheid Kratzer8,9, Sandeep Kumar 10, Flávia Rezende1,2, Ivana Josipovic1,2, Dominique Thomas11, Hector Giral8,9, Yannick Schreiber12, Gerd Geisslinger11,12, Christian Fork1,2, Xia Yang13, Fragiska Sigala14, Casey E. Romanoski15, Jens Kroll7, Hanjoong Jo 10, Ulf Landmesser8,9,16, Aldons J. Lusis17, 1234567890():,; Dmitry Namgaladze18, Ingrid Fleming2,6, Matthias S. Leisegang1,2, Jun Zhu 3,4 & Ralf P. Brandes1,2 Oxidized phospholipids (oxPAPC) induce endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Here we show that oxPAPC induce a gene network regulating serine-glycine metabolism with the mitochondrial methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase (MTHFD2) as a cau- sal regulator using integrative network modeling and Bayesian network analysis in human aortic endothelial cells. The cluster is activated in human plaque material and by atherogenic lipo- proteins isolated from plasma of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the MTHFD2-controlled cluster associate with CAD. The MTHFD2-controlled cluster redirects metabolism to glycine synthesis to replenish purine nucleotides. Since endothelial cells secrete purines in response to oxPAPC, the MTHFD2- controlled response maintains endothelial ATP. Accordingly, MTHFD2-dependent glycine synthesis is a prerequisite for angiogenesis. Thus, we propose that endothelial cells undergo MTHFD2-mediated reprogramming toward serine-glycine and mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism to compensate for the loss of ATP in response to oxPAPC during atherosclerosis. -

RBX1/ROC1 Disruption Results in Early Embryonic Lethality Due to Proliferation Failure, Partially Rescued by Simultaneous Loss of P27

RBX1/ROC1 disruption results in early embryonic lethality due to proliferation failure, partially rescued by simultaneous loss of p27 Mingjia Tana, Shannon W. Davisb, Thomas L. Saundersc, Yuan Zhud, and Yi Suna,1 aDivision of Radiation and Cancer Biology, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, 4424B MS I, 1301 Catherine Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5936; bDepartment of Human Genetics, 4909 Buhl SPC 5618, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0669; cDivision of Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, Transgenic Animal Model Core, Biomedical Research Core Facilities, 2570 MSRB II, SPC 5674, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0618; and dDivision of Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Departments of Internal Medicine and Cell and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan Medical School, 2061 BSRB, 109 Zina Pitcher, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2200 Edited by Carol L. Prives, Columbia University, New York, NY, and approved by the Editorial Board February 17, 2009 (received for review December 8, 2008) RBX1 (RING box protein-1) or ROC1 (regulator of cullins-1) is the vivo physiological function of RBX1 in mouse remains unchar- RING component of SCF (Skp1, Cullins, F-box proteins) E3 ubiquitin acterized. Here, we use a gene trap allele of Rbx1 to generate ligases, which regulate diverse cellular processes by targeting Rbx1Gt/Gt embryos, and found that these embryos fail to ade- various substrates for degradation. However, the in vivo physio- quately proliferate and die at embryonic day (E)7.5 with a logical function of RBX1 remains uncharacterized. Here, we show remarkable accumulation of p27. -

The Regulation of Cyclin D1 Degradation: Roles in Cancer Development and the Potential for Therapeutic Invention John P Alao*

Molecular Cancer BioMed Central Review Open Access The regulation of cyclin D1 degradation: roles in cancer development and the potential for therapeutic invention John P Alao* Address: Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Lundberg Laboratory, Gothenburg University, P. O. Box 462, S-405 30, Gothenburg, Sweden Email: John P Alao* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 2 April 2007 Received: 15 March 2007 Accepted: 2 April 2007 Molecular Cancer 2007, 6:24 doi:10.1186/1476-4598-6-24 This article is available from: http://www.molecular-cancer.com/content/6/1/24 © 2007 Alao; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Cyclin D1 is an important regulator of cell cycle progression and can function as a transcriptionl co-regulator. The overexpression of cyclin D1 has been linked to the development and progression of cancer. Deregulated cyclin D1 degradation appears to be responsible for the increased levels of cyclin D1 in several cancers. Recent findings have identified novel mechanisms involved in the regulation of cyclin D1 stability. A number of therapeutic agents have been shown to induce cyclin D1 degradation. The therapeutic ablation of cyclin D1 may be useful for the prevention and treatment of cancer. In this review, current knowledge on the regulation of cyclin D1 degradation is discussed. Novel insights into cyclin D1 degradation are also discussed in the context of ablative therapy. -

Supplementary Table 1. a List of All 142 Genes Important in the P53 Stress Response and Included Into the Genomic Scan for Natural Selection

Supplementary table 1. A list of all 142 genes important in the p53 stress response and included into the genomic scan for natural selection. Gene Symbol Description AKT1 v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 AKT2 v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2 APAF1 apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 APC adenomatous polyposis coli APEX1 APEX nuclease (multifunctional DNA repair enzyme) 1 ATM ataxia telangiectasia mutated ATR ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related AURKA aurora kinase A BAI1 brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1 BAX BCL2-associated X protein BBC3 BCL2 binding component 3 CCNG1 cyclin G1 CD82 CD82 molecule CDK2 cyclin-dependent kinase 2 CDK8 cyclin-dependent kinase 8 CDKN1A cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21, Cip1) CDKN1B cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27, Kip1) CDKN2A cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (melanoma, p16, inhibits CDK4) CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) CORO1B coronin, actin binding protein, 1B CREB1 cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 CREBBP CREB binding protein (Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome) CSE1L CSE1 chromosome segregation 1-like (yeast) CSNK2A1 casein kinase 2, alpha 1 polypeptide CTNNB1 catenin (cadherin-associated protein), beta 1, 88kDa CUL7 cullin 7 DUSP1 dual specificity phosphatase 1 DUSP16 dual specificity phosphatase 16 DYRK2 dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 2 E2F1 E2F transcription factor 1 E4F1 E4F transcription factor 1 EEF1A1 eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1 EIF4EBP1 eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 ESR1 estrogen receptor 1 ESR2 estrogen receptor 2 (ER beta) FAS Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) FCGR1A Fc fragment of IgG, high affinity Ia, receptor (CD64) FHL2 four and a half LIM domains 2 FLT1 fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 (vasc. -

Induction of Cullin 7 by DNA Damage Attenuates P53 Function

Induction of Cullin 7 by DNA damage attenuates p53 function Peter Jung*, Berlinda Verdoodt*, Aaron Bailey†, John R. Yates III†, Antje Menssen*, and Heiko Hermeking*‡ *Molecular Oncology, Max-Planck-Institute of Biochemistry, D-82152 Martinsried, Germany; and †Department of Cell Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037 Edited by Bert Vogelstein, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD, and approved May 18, 2007 (received for review October 26, 2006) The p53 tumor suppressor gene encodes a transcription factor, specificity (17). Association with the SCF7 complex is required which is translationally and posttranslationally activated after for cellular transformation by SV40 large T antigen (18). Cul7 is DNA damage. In a proteomic screen for p53 interactors, we found highly homologous to PARC (PARkin-like, cytoplasmic, p53- that the cullin protein Cul7 efficiently associates with p53. After binding protein), which negatively regulates p53 by cytoplasmic DNA damage, the level of Cul7 protein increased in a caffeine- sequestration (19). PARC has been shown to heterodimerize sensitive, but p53-independent, manner. Down-regulation of Cul7 with Cul7 (20). The two proteins have nonoverlapping functions by conditional microRNA expression augmented p53-mediated because deletion of PARC in mice has no effect on viability (20), inhibition of cell cycle progression. Ectopic expression of Cul7 whereas Cul7-deficient mice exhibit neonatal lethality with inhibited activation of p53 by DNA damaging agents and sensitized reduced size and vascular defects (21). cells to adriamycin. Although Cul7 recruited the F-box protein Using a proteomic approach, we identified Cul7 as a p53- FBX29 to p53, the combined expression of Cul7/FBX29 did not interacting protein.