Tompkins 2016, Grassroots Transnationalisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns Second Edition

handbook_2014.qxp 17/06/2014 19:40 Page 1 Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns Second Edition Published by War Resisters’ International Second Edition June 2014 ISBN 978-0-903517-28-7 Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/uk/) 1 handbook_2014.qxp 17/06/2014 19:40 Page 2 2 handbook_2014.qxp 17/06/2014 19:40 Page 3 CREDITS The process of writing this Handbook was a collective effort, with people from across the world (more than 20 countries) contributing their time, skills, knowledge and resources. The first edition was translated into 10 languages. The second edition was expanded on by a range of writers and contributors. All of the content and translations are available for free online at http://wri-irg.org/pubs/NonviolenceHandbook Coordinator: Andrew Dey Editorial Committee: Javier Gárate, Subhash Kattel, Christine Schweitzer and Joanne Sheehan Editorial consultant: Mitzi Bales Layout: Contributors to both editions of the handbook include: Ahmadullah Archiwal, Eric Bachman, Roberta Bacic, Jagat Basnet, April Carter, Janet Cherry, Jungmin Choi, Howard Clark, Jake Coleman, Lavinia Crossley, Jagat Deuja, Denise Drake, Hilal Demir, Luke Finn, Abraham Gebreyesus Mehreteab, Dan Glass, Symon Hill, Ruth Hiller, Ippy, Yeo Jeewoo, Jørgen Johansen, Sian Jones, Randy Kehler, Adele Kirsten, Boro Kitanoski, Hans Lammerant, Cattis Laska, Tali Lerner, Benard Lisamadi Agona, Dieter Lünse, Brian Martin, Jason MacLeod, Shannon McManimon, Rosa Moiwend, Michael Randle, Andrew Rigby, Vicki Rovere, Chesterfield Samba, Ruben Dario Santamaria, Vivien Sharples, Martin Smedjeback, Majken Sorensen, Andreas Speck, Jill Sternberg, Roel Stynen, Miles Tanhira, Katja Tempel, Cecil Barbeito Thonon, Ferda Ûlker, Sahar Vardi, Stellan Vinthagen, Steve Whiting, Dorie Wilsnack. -

Die Vollständigen Libertären Buchseiten Als

libertäre GWR 387 märz 2014/387 graswurzelrevolution März 2014 buchseiten Libertäre Buchseiten Graswurzelrevolution (GWR) Breul 43, D-48143 Münster libertäre buchseiten beilage zu graswurzelrevolution 387, märz 2014 Verlag Graswurzelrevolution auf der Leipziger Buchmesse, www.graswurzel.net 13. – 16.3.2014, Halle 5, C 407 Tardis Geschichte der Besiegten „Nicht das klassische, weiße Seite 3 Kommen Sie da Bild des Kollektivs“ runter! Seite 4 Ein Gespräch mit Willi Bischof und Carina Büker (Verlag edition assemblage) Anarchismus Hoch 2 „Assemblage ist ursprünglich in Seite 5 der Bildenden Kunst zu einem Begriff mit besonderer Bedeu- tung geworden, der eine Art Buch des Jahres von Kunstwerken bezeichnet. ... Seite 6 Gilles Deleuze und Felix Guattari ... verstehen unter ‘Assemblage’ ein ‘kontingentes Schwarze Flamme Ensemble von Praktiken und Seite 7 Gegenständen, zwischen denen unterschieden werden kann’ (d. h. sie sind keine Ansammlungen Marx und Bakunin von Gleichartigem), ‘die entlang Seite 8 den Achsen von Territorialität und Entterritorialisierung ausgerichtet’ werden können. Resistencia! Damit vertreten sie die These, Seite 8 dass bestimmte Mixturen technischer und administrativer Praktiken neue Räume erschlie- David Graeber: ßen und verständlich machen, Direkte Aktion indem sie Milieus dechiffrieren und neu kodieren.“ (Wikipedia). Seite 9 2011 wurde der Verlag „edition assemblage“ gegründet. Er Genagelt versteht sich als „gesellschafts- kritisches, linkes, politisches Seite 10 und publizistisches Netzwerk“ und erhebt für sich den Widerstand in Indien Anspruch, „thematisch die gesamte gesellschaftskritische Ann-Kathrin Petermann, Willi Bischof und Carina Büker (edition assemblage) Foto: Bernd Drücke Seite 10 f. Breite radikaler linker Politik und Bewegung und kritische Schritt für Schritt ins Wissenschaften zu vertreten“. dann hingegangen und anstatt hin zu Romanen, Kurzge- Utopiegedanken kritisch denkt. -

Bulletin N°75

Centre International de Recherches sur l’Anarchisme Bulletin du CIRA 75 PRINTEMPS 2019 Bulletin du CIRA Lausanne N°75, printemps 2019 Sommaire Rapport d'activités 2018 p.2 Les pompiers de La NouvelleOrléans au XIXe siècle et Elisée Reclus p.7 Science Popularization and Romanian Anarchism in the NineteenthCentury p.10 Peau de reptile pour cordonniers mal chaussés? p.20 Lucien Grelaud, 19302019 p.21 Papa Michel p.25 Ressources en ligne: Le dictionnaire Maîtron p.28 Bibliografia dei periodici italiani p.30 Han Ryner, LacazeDuthiers et Devaldès p.31 Hommage à Bocs p.32 Dieter Gebauer, 19442018 p.34 Liste des périodiques vivants parus et conservés au CIRA en 2017 et 2018 p.36 Liste des nouvelles acquisitions p.40 1 Rapport d’activités 2018 Fonctionnement Les inquiétudes et réflexions se Le fonctionnement de la biblio sont poursuivies en 2018 quant à la thèque est toujours assuré par une question de l'espace disponible dans petite équipe de base qui, à tour de la bibliothèque, toujours plus res rôle, tient les permanences du mar treint face au volume croissant de di au vendredi aprèsmidi, avec la documents que nous conservons. De présence quotidienne d'un voire manière générale, deux solutions deux civilistes et des coups de sont envisagées: soit réduire le mains extérieurs plus ou moins ré nombre de documents, par exemple guliers. Pour le moment, cette orga en « désherbant », soit trouver de nisation fonctionne bien, même si nouveaux espaces de stockage. La nous sommes toujours à la re première a été évoquée mais pas cherche de personnes prêtes à s'en réellement mise en pratique; gager de façon régulière pour concernant la seconde, plusieurs dé mener à bien les tâches et projets cisions sont intervenues en 2018 qui se multiplient. -

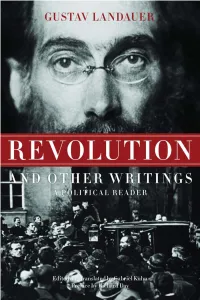

Praise for Revolution and Other Writings: a Political Reader

PRAISE FOR REVOLUTION AND OTHER WRITINGS: A POLITICAL READER If there were any justice in this world – at least as far as historical memory goes – then Gustav Landauer would be remembered, right along with Bakunin and Kropotkin, as one of anarchism's most brilliant and original theorists. Instead, history has abetted the crime of his murderers, burying his work in silence. With this anthology, Gabriel Kuhn has single-handed- ly redressed one of the cruelest gaps in Anglo-American anarchist litera- ture: the absence of almost any English translations of Landauer. – Jesse Cohn, author of Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics Gustav Landauer was, without doubt, one of the brightest intellectual lights within the revolutionary circles of fin de siècle Europe. In this remarkable anthology, Gabriel Kuhn brings together an extensive and splendidly chosen collection of Landauer's most important writings, presenting them for the first time in English translation. With Landauer's ideas coming of age today perhaps more than ever before, Kuhn's work is a valuable and timely piece of scholarship, and one which should be required reading for anyone with an interest in radical social change. – James Horrox, author of A Living Revolution: Anarchism in the Kibbutz Movement Kuhn's meticulously edited book revives not only the "spirit of freedom," as Gustav Landauer put it, necessary for a new society but also the spirited voice of a German Jewish anarchist too long quieted by the lack of Eng- lish-language translations. Ahead of his time in many ways, Landauer now speaks volumes in this collection of his political writings to the zeitgeist of our own day: revolution from below. -

According to Gustav Landauer, Waiting for a Sufficiently Advanced Level of Technological Development to Trigger a Disruption of Social Relations Is Not the Answer

BARBARA KUON Gustav Landauer, a common individual How does a revolution take place? According to Gustav Landauer, waiting for a sufficiently advanced level of technological development to trigger a disruption of social relations is not the answer. Nor is it a question of unleashing revolutionary violence in a relentless struggle against bourgeoisie and conservatism. On the contrary, each project of a social revolution ought to be preceded by an individual revolution, which would be accomplished as a self-transformation of the individual into a collective self (or as “common individual” as Jean-Paul Sartre would put it). Both an anarchist and an atheist, Landauer reminds us - as does Carl Schmidt but in a quite different manner - that all political notions are theological notions. To become a socialist means “closing one’s eyes” (according to the old mystical project which was resuscitated to become the “Gesamtkunstwerk” project, that is the “total work of art project”). This project implies blocking the discriminating sense - sight - in order to create a synaesthetic perception which would allow society to integrate the individual as well as allow the individual to integrate society. So Landauer concludes: when we are most individualistic, we are at the same time the most common (“Unser Allerindividuellstes ist unser Allerallgemeinstes.”) In the face of this growing individualism (or “narcissism”) that keeps on dissolving family or social and traditional relations as well as diminishing the power of communist or socialist parties, the analysis of Gustav Landauer’s philosophical and revolutionary project - enriched by Oscar Wilde’s reflection on the link between the artist and socialism - enables us to conceive the seemingly unlikely conjunction of sharp individualism and social equality. -

Annual Report 2014 L URG ROSA UXEMB STIFTUNG

AnnuAl report 2014 ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG AnnuAl RepoRt 2014 of the Rosa-LuxembuRg-stiftung 1 Contents editoRiAl 4 FoCus: ReFugees And Asylum 6 Lampedusa in Germany 7 “Strom & Wasser” – rafting tour in summer 2014 9 Refugees Welcome – what do you mean by “welcome”? 10 Project funding linked to our key issue 12 Racism in healthcare 12 Providing support across national borders 13 the institute FoR CRitical soCiAl AnAlysis 14 Fellowships 15 We do care! Caring (instead of worrying) about tomorrow 16 2nd Strike Conference in Hannover 17 Attacks on democracy as a form of life 18 Luxemburg lectures 18 the Academy FoR political education 20 TTIP and TISA 21 The Swedish artist Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss in Germany 22 Politics as a Project of Change 22 New format: educational materials 23 the FoundAtion’s netwoRk 24 Educational work in the regions 24 Baden-Württemberg: In honor of Ernst and Karola Bloch 26 Bavaria: Lay down your arms! 26 Berlin: Edward Snowden – who can protect us from the NSA? 27 Brandenburg: The path to German reunification 27 Bremen: Drone wars 28 Hamburg: South Africa in 2014 – twenty years since apartheid 28 Hesse: Rojava and the “terror caliphate” 29 Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania: The Benjamins – a German family 29 Lower Saxony: The event series “Soccer and Society” 30 North Rhine-Westphalia: (Re)organize the Left in crisis 30 Rhineland-Palatinate: Jenny Marx’s 200th birthday 31 Saarland: Lentils from Saint Petersburg 31 Saxony: Sustainability versus the growth paradigm 32 Saxony-anhalt: Second flood conference in Magdeburg -

The Intimate Enemy As a Classic Post-Colonial Study of M

critical currents Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Occasional Paper Series Camus and Gandhi Essays on Political Philosophy in Hammarskjöld’s Times no.3 April 2008 Beyond Diplomacy – Perspectives on Dag Hammarskjöld 1 critical currents no.3 April 2008 Camus and Gandhi Essays on Political Philosophy in Hammarskjöld’s Times Lou Marin Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala 2008 The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation pays tribute to the memory of the second Secretary-General of the UN by searching for and examining workable alternatives for a socially and economically just, ecologically sustainable, peaceful and secure world. Critical Currents is an In the spirit of Dag Hammarskjöld's Occasional Paper Series integrity, his readiness to challenge the published by the dominant powers and his passionate plea Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation. for the sovereignty of small nations and It is also available online at their right to shape their own destiny, the www.dhf.uu.se. Foundation seeks to examine mainstream understanding of development and bring to Statements of fact or opinion the debate alternative perspectives of often are those of the authors and unheard voices. do not imply endorsement by the Foundation. By making possible the meeting of minds, Manuscripts for review experiences and perspectives through the should be sent to organising of seminars and dialogues, [email protected]. the Foundation plays a catalysing role in the identifi cation of new issues and Series editor: Henning Melber the formulation of new concepts, policy Language editor: Wendy Davies proposals, strategies and work plans towards Layout: Mattias Lasson solutions. The Foundation seeks to be at the Printed by X-O Graf Tryckeri AB cutting edge of the debates on development, ISSN 1654-4250 security and environment, thereby Copyright on the text is with the continuously embarking on new themes authors and the Foundation. -

International Medical Corps Afghanistan

Heading Folder Afghanistan Afghanistan - Afghan Information Centre Afghanistan - International Medical Corps Afghanistan - Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) Agorist Institute Albee, Edward Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres American Economic Association American Economic Society American Fund for Public Service, Inc. American Independent Party American Party (1897) American Political Science Association (APSA) American Social History Project American Spectator American Writer's Congress, New York City, October 9-12, 1981 Americans for Democratic Action Americans for Democratic Action - Students for Democractic Action Anarchism Anarchism - A Distribution Anarchism - Abad De Santillan, Diego Anarchism - Abbey, Edward Anarchism - Abolafia, Louis Anarchism - ABRUPT Anarchism - Acharya, M. P. T. Anarchism - ACRATA Anarchism - Action Resource Guide (ARG) Anarchism - Addresses Anarchism - Affinity Group of Evolutionary Anarchists Anarchism - Africa Anarchism - Aftershock Alliance Anarchism - Against Sleep and Nightmare Anarchism - Agitazione, Ancona, Italy Anarchism - AK Press Anarchism - Albertini, Henry (Enrico) Anarchism - Aldred, Guy Anarchism - Alliance for Anarchist Determination, The (TAFAD) Anarchism - Alliance Ouvriere Anarchiste Anarchism - Altgeld Centenary Committee of Illinois Anarchism - Altgeld, John P. Anarchism - Amateur Press Association Anarchism - American Anarchist Federated Commune Soviets Anarchism - American Federation of Anarchists Anarchism - American Freethought Tract Society Anarchism - Anarchist -

Revolution and Other Writings: a Political Reader

PRAISE FOR REVOLUTION AND OTHER WRITINGS: A POLITICAL READER If there were any justice in this world – at least as far as historical memory goes – then Gustav Landauer would be remembered, right along with Bakunin and Kropotkin, as one of anarchism's most brilliant and original theorists. Instead, history has abetted the crime of his murderers, burying his work in silence. With this anthology, Gabriel Kuhn has single-handed- ly redressed one of the cruelest gaps in Anglo-American anarchist litera- ture: the absence of almost any English translations of Landauer. – Jesse Cohn, author of Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics Gustav Landauer was, without doubt, one of the brightest intellectual lights within the revolutionary circles of fin de siècle Europe. In this remarkable anthology, Gabriel Kuhn brings together an extensive and splendidly chosen collection of Landauer's most important writings, presenting them for the first time in English translation. With Landauer's ideas coming of age today perhaps more than ever before, Kuhn's work is a valuable and timely piece of scholarship, and one which should be required reading for anyone with an interest in radical social change. – James Horrox, author of A Living Revolution: Anarchism in the Kibbutz Movement Kuhn's meticulously edited book revives not only the "spirit of freedom," as Gustav Landauer put it, necessary for a new society but also the spirited voice of a German Jewish anarchist too long quieted by the lack of Eng- lish-language translations. Ahead of his time in many ways, Landauer now speaks volumes in this collection of his political writings to the zeitgeist of our own day: revolution from below. -

Libertäre Buchseiten GWR 417 März 2017

märz 2017/417 graswurzelrevolution libertäre libertäre buchseiten buchseiten beilage zu graswurzelrevolution nr. 417, märz 2017 GWR 417 März 2017 Libertäre Buchseiten Graswurzelrevolution (GWR) Breul 43, D-48143 Münster www.graswurzel.net Verlag Graswurzelrevolution auf der Leipziger Buchmesse: 23. bis 26.3.2017, Halle 5, E 409 Zeichnung: Jesse Purcell of Just Seeds. Montreal Anarchist Bookfair collective. Montreal-Anarchist-Bookfair-2010-Plakat: www.anarchistbookfair.ca/archives/posters V.i.S.d.P.: Bernd Drücke libertäre graswurzelrevolution märz 2017/417 buchseiten Ein Sachcomic gegen die Militarisierung Findus, Michael Schulze von Den Leserinnen und Lesern der der Geschichte wird mit Hilfe Glaßer: Kleine Geschichte der Monatszeitschrift „Graswurzel- der JungaktivistInnen Lilly und Kriegsgegnerschaft. revolution“ (GWR) sind Findus Felix gesponnen, die am Anfang Friedensbewegung und und Michael Schulze von Glaß- des Comics auf dem Weg zu ei- Antimilitarismus in er bekannt. Findus zeichnet seit ner Aktion gegen einen Bundes- Deutschland von 1800 bis vielen Jahren für fast jede Aus- wehrpropagandastand auf eine heute, Unrast Verlag, Münster gabe der GWR und hat mit sei- Demo der Friedensbewegung 2016, 80 Seiten, 9,80 Euro, nen Illustrationen dazu beigetra- stoßen. Hier kommt es zu einer ISBN 978-3-89771-215-7 gen, dass die Monatszeitung für Diskussion mit älteren Friedens- eine gewaltfreie, herrschaftslose aktivistInnen, in deren Verlauf Gesellschaft ihr altes Image als die Geschichte der Kriegsgeg- „Bleiwüstenrevolution“ heute nerschaft gezeichnet wird. Da- weitgehend verloren hat. bei geht es um die Gründung der Der im Verlag Graswurzelrevo- ersten Friedensgesellschaften lution erschienene schwarz-rote 1815, die Geschichte der DFG- Leitfaden „Kleine Geschichte VK und den Kampf von Anar- des Anarchismus“ von Findus chistInnen und MarxistInnen ist ein mittlerweile in überar- gegen Krieg und Waffenexpor- beiteter Neuauflage erhältlicher te. -

Anti-‐Nuclear Activism in the Rhine Valley A

“Today the Fish, Tomorrow Us:” Anti-Nuclear Activism in the Rhine Valley and Beyond, 1970-1979 Stephen Milder A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill, 2012 Approved by: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Dr. Miles Fletcher Dr. Lawrence Goodwyn Dr. Karen Hagemann Dr. Holger Moroff Dr. Donald Reid ©2012 Stephen Milder ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT STEPHEN MILDER: “Today the Fish, Tomorrow Us:” Anti-Nuclear Activism in the Rhine Valley and Beyond, 1970-1979 (under the direction of Konrad H. Jarausch) My dissertation analyZes the growth and development of the anti-nuclear movement in Western Europe during the 1970s. The primary focus of my research is a series of anti-reactor protests that spanned the Rhine River, connecting rural villages in German Baden, the French Alsace, and Northwest SwitZerland. I seek to explain how these grassroots protests influenced public opinion about nuclear energy far from the Rhine Valley and spawned national anti-nuclear movements. I argue that democracy matters played a key role in grassroots protesters’ coalescence around the issue of nuclear energy and the growth of their movement beyond the local level. After politicians repeatedly dismissed their constituents’ concerns about the proposed “nuclearization” of the Rhine, local people created a trans-national “imagined community” as an alternative to the state, and national governments that they considered dysfunctional. Thus the association of nuclear energy with democracy matters achieved by local protesters in the Rhine Valley, many of whom were conservative farmers, was a key step towards the rise of mass anti-nuclear movements and the emergence of environmental values in Western Europe during the 1970s.