Redistribution 3. Wealth Inequality in the 2Nd Dimension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50Th Anniversary: Experiencing History(S) (PDF, 2.01MB)

asf_england_druck_1 22.07.11 10:01 Seite 1 Experiencing History(s) 50 Years of Action Reconciliation Service for Peace in the UK asf_england_druck_1 22.07.11 10:01 Seite 2 Published by: Action Reconciliation Service for Peace St Margaret's House, 21 Old Ford Road, London E2 9PL United Kingdom Telephone: (44)-0-20-8880 7526 Fax: (44)-0-20-8981 9944 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.asf-ev.de/uk Editors: Magda Schmukalla, Heike Kleffner, Andrea Koch Special thanks to Daniel Lewis for proof-reading, Al Gilens for his contributions and Karl Grünberg for photo editing. Photo credits: ASF-Archives p. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 23, 26, 29, 34, 36, 37, 38, 40; International Youth Center in Dachau p. 30; Immanuel Bartz p. 14; Agnieszka Bieniek p. 4; Al Gilens p. 17, 22; Maria Kozlowska p. 28; Manuel Holtmann p. 25; Lena Mangold p. 41; Roy Scriver p. 33; Saskia Spahn p. 20 Title: ARSP volunteer Lena Mangold and Marie Simmonds; Lena Mangold Graphics and Design: Anna-Maria Roch Printed by: Westkreuz Druckerei Ahrens, Berlin 500 copies, London 2011 Donations: If you would like to make a donation, you can do so by cheque (payable to UK Friends of ARSP) or by credit card. UK Friends of ARSP is a registered charity, number 1118078. Donations account: UK Friends of ARSP: Sort Code: 08 92 99 Account No: 65222386 Thank you very much! 2 asf_england_druck_1 22.07.11 10:01 Seite 3 Table of Contents Introduction 4 by Dr. Elisabeth Raiser Working Beyond Ethnic and Cultural Differences 6 Voices of Project Partners Five Decades of ARSP in the UK: Turbulent Times 8 by Andrea Koch Reflecting History 12 by Dr. -

WARD: Gorse Hill 1308 (08/18) TRAFFORD METROPOLITAN

TRAFFORD METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL Report to: Executive Member for Environment, Air Quality and Climate Change Date: September 2018 Report for: Approval Report of: Principal Engineer, Traffic and Transportation, One Trafford. ELTON STREET, STRETFORD Proposal to introduce a new Disabled Residents’ Permit Parking Space Consideration of objections and proposal to introduce a 2nd disabled residents’ permit bay Summary To consider the objection received and to seek approval to introduce a new disabled residents’ permit parking space on Elton Street, Stretford To seek approval to advertise the intention to introduce a second disabled residents’ permit parking space on Elton Street, Stretford Recommendations Agreement is sought to the following: 1. That the introduction of a disabled residents’ permit parking space on Elton Street, Stretford be approved. 2. That, following careful consideration of the objection received, authorisation be given to make and introduce the Traffic Regulation Order, as advertised. 3. That the objector be notified of the Council’s decision. 4. That the introduction of a second disabled residents’ permit parking space on Elton Street, Stretford be approved. 5. That authorisation be given to advertise the intention of making the Traffic Regulation Order referred to in schedule 3 to this report and, if no objections are maintained, that the Order be made and the proposal implemented. 6. That a consultation be carried out with nearby residents. Contact person for further information: Name: Dorothy Stagg Extension: 0161 6726534 Background Papers: None WARD: Gorse Hill 1308 (08/18) 1.0 BACKGROUND 1.1 Following the receipt of a request from a disabled resident of 18 Elton Street, Stretford, who is a blue badge holder, a report was circulated in January 2018, considering a proposal to introduce a disabled persons’ permit bay. -

North Locality: Life Expectancy

TRAFFORD NORTH LOCALITY HEALTH PROFILE JANUARY 2021 NORTH LOCALITY: WARDS • Clifford: Small and densely populated ward at north-east tip of the borough. Dense residential area of Victorian terraced housing and a diverse range of housing stock. Clifford has a diverse population with active community groups The area is undergoing significant transformation with the Old Trafford Master Plan. • Gorse Hill: Northern most ward with the third largest area size. Trafford town hall, coronation street studio and Manchester United stadium are located in this ward. Media city development on the Salford side has led to significant development in parts of the ward. Trafford Park and Humphrey Park railway stations serve the ward for commuting to both Manchester and Liverpool. • Longford: Longford is a densely populated urban area in north east of the Borough. It is home to the world famous Lancashire County Cricket Club. Longford Park, one of the Borough's larger parks, has been the finishing point for the annual Stretford Pageant. Longford Athletics stadium can also be found adjacent to the park. • Stretford: Densely populated ward with the M60 and Bridgewater canal running through the ward. The ward itself does not rank particularly highly in terms of deprivation but has pockets of very high deprivation. Source: Trafford Data Lab, 2020 NORTH LOCALITY: DEMOGRAPHICS • The North locality has an estimated population of 48,419 across the four wards (Clifford, Gorse Hill, Stretford & Longford) (ONS, 2019). • Data at the ward level suggests that all 4 wards in the north locality are amongst the wards with lowest percentages of 65+ years population (ONS, 2019). -

Central Ward

Swindon Borough Council Open Space Audit and Assessment Update Part B: Ward Profiles March 2014 Open Space Audit and Assessment Update: Part B NOTES 1. For the purposes of assessing open space provision, the standard of 3.2 ha per 1000 population will be used as set out in the Swindon Borough Local Plan 2011 (saved policy R4 ‘Protection of Recreation Open Space’ (March 2011)). The draft Swindon Borough Local Plan 2026 seeks to continue this standard and will inform emerging work on Green Infrastructure. 2. This update has predominantly been prepared to reflect the ward boundary changes in 2012; data collated in May 2010 has therefore been used for this update to the open space ward profiles. 3. Outdoor sports facilities and playing pitches have not been updated since the review of the Playing Pitch Strategy in 2007. An update of the Playing Pitch Strategy will be undertaken in 2014. 4. All school playing fields and private pitches that do not have community access have been excluded from these profiles. 5. Playing pitches with community access are included within the overall totals for outdoor sports facilities. 6. Where country parks and golf courses exist, they have been listed in the Ward Profile schedules; however they do not contribute towards the open space standard as they are considered to be a Borough wide resource. 7. All population figures have been taken from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Census 2011. A SASPEC methodology was then used to align the data with the revised Swindon Borough ward boundaries. 8. The quality for each open space is illustrated through the use of the following colours: Quality Standard Scoring Range Colour Under Standard Under 49.99% At Standard 50% - 69.99% Above standard Above 70% 9. -

Housing, Credit and Brexit

Housing, Credit and Brexit Ben Ansell∗ Abstract Dozens of articles have been drafted attempting to explain the narrow vic- tory for the Leave campaign in Britain’s EU referendum in June 2016. Yet, hitherto, and despite a general interest in ‘Left Behind’ commentary, few writ- ers have drawn attention to the connection between the Brexit vote and the distribution of British housing costs. This memo examines the connection be- tween house prices and both aggregate voting during the EU referendum and individual vote intention beforehand. I find a very strong connection at the local authority, ward, and individual level between house prices and support for the Remain campaign, one that even holds up within regions and local authorities. Preliminary analysis suggests that housing values reflect long-run social differences that are just as manifest in attitudes to immigration as Brexit. Local ‘ecologies of unease’ (Reeves and Gimpel, 2012) appear a crucial force behind Brexit. This is a short memo on housing, credit and Brexit to be presented at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, April 2017. ∗Professor of Comparative Democratic Institutions, Nuffield College, University of Oxford. [email protected]. My acknowledgements and thanks go to Jane Gingrich for the provision of local economic and housing data. 1 1 Introduction If there is one saving grace of Brexit for the British higher education system it is a boom of Brexit studies that began pouring forth as the dust settled on June 24th 2016. Most scholars have coalesced around an understanding of Brexit that to some extent mirrors that implicit in Theresa May’s quasi hard Brexit strategy - Brexit was caused by both economic and cultural forces, with opposition to the European Union based on concerns about immigration and of declining cultural and social status rather than economic deprivation or actual migration levels per se (Kaufmann, 2016). -

DOWNLOAD London.PDF • 5 MB

GORDON HILL HIGHLANDS 3.61 BRIMSDOWN ELSTREE & BOREHAMWOOD ENFIELD CHASE ENFIELD TOWN HIGH BARNET COCKFOSTERS NEW BARNET OAKWOOD SOUTHBURY SOUTHBURY DEBDEN 9.38 GRANGE PARK PONDERS END LOUGHTON GRANGE BUSH HILL PARK COCKFOSTERS PONDERS END 6.83 4.96 3.41 OAKLEIGH PARK EAST BARNET SOUTHGATE 4.03 4.01 JUBILEE CHINGFORD WINCHMORE HILL BUSH HILL PARK 6.06 SOUTHGATE 4.24 CHINGFORD GREEN TOTTERIDGE & WHETSTONE WINCHMORE HILL BRUNSWICK 2.84 6.03 4.21 ENDLEBURY 2.89 TOTTERIDGE OAKLEIGH EDMONTON GREEN LOWER EDMONTON 3.10 4.11 3.57 STANMORE PALMERS GREEN HASELBURY SOUTHGATE GREEN 5.94 CHIGWELL WOODSIDE PARK PALMERS GREEN 5.23 EDMONTON GREEN 3.77 ARNOS GROVE 10.64 LARKSWOOD RODING VALLEY EDGWARE SILVER STREET MILL HILL BROADWAY 4.76 MONKHAMS GRANGE HILL NEW SOUTHGATE VALLEY HATCH LANE UPPER EDMONTON ANGEL ROAD 8.04 4.16 4.41 MILL WOODHOUSE COPPETTS BOWES HATCH END 5.68 9.50 HILL MILL HILL EAST WEST FINCHLEY 5.12 4.41 HIGHAMS PARK CANONS PARK 6.07 WEST WOODFORD BRIDGE FINCHLEY BOUNOS BOWES PARK 3.69 5.14 GREENBOUNDS GREEN WHITE HART LANE NORTHUMBERLAND PARK HEADSTONE LANE BURNT OAK WOODSIDE WHITE HART LANE HAINAULT 8.01 9.77 HALE END FAIRLOP 4.59 7.72 7.74 NORTHUMBERLAND PARK AND BURNT OAK FINCHLEY CENTRAL HIGHAMS PARK 5.93 ALEXANDRA WOOD GREEN CHURCH END RODING HIGHAM HILL 4.58 FINCHLEY 4.75 ALEXANDRA PALACE CHAPEL END 3.13 4.40 COLINDALE EAST 5.38 FULLWELL CHURCH 5.25 FAIRLOP FINCHLEY BRUCE 5.11 4.01 NOEL PARK BRUCE GROVE HARROW & WEALDSTONE FORTIS GREEN GROVE TOTTENHAM HALE QUEENSBURY COLINDALE 4.48 19.66 PINNER 3.61 SOUTH WOODFORD HENDON WEST -

NRT Index Stations

Network Rail Timetable OFFICIAL# May 2021 Station Index Station Table(s) A Abbey Wood T052, T200, T201 Aber T130 Abercynon T130 Aberdare T130 Aberdeen T026, T051, T065, T229, T240 Aberdour T242 Aberdovey T076 Abererch T076 Abergavenny T131 Abergele & Pensarn T081 Aberystwyth T076 Accrington T041, T097 Achanalt T239 Achnasheen T239 Achnashellach T239 Acklington T048 Acle T015 Acocks Green T071 Acton Bridge T091 Acton Central T059 Acton Main Line T117 Adderley Park T068 Addiewell T224 Addlestone T149 Adisham T212 Adlington (cheshire) T084 Adlington (lancashire) T082 Adwick T029, T031 Aigburth T103 Ainsdale T103 Aintree T105 Airbles T225 Airdrie T226 Albany Park T200 Albrighton T074 Alderley Edge T082, T084 Aldermaston T116 Aldershot T149, T155 Aldrington T188 Alexandra Palace T024 Alexandra Parade T226 Alexandria T226 Alfreton T034, T049, T053 Allens West T044 Alloa T230 Alness T239 Alnmouth For Alnwick T026, T048, T051 Alresford (essex) T011 Alsager T050, T067 Althorne T006 Page 1 of 53 Network Rail Timetable OFFICIAL# May 2021 Station Index Station Table(s) Althorpe T029 A Altnabreac T239 Alton T155 Altrincham T088 Alvechurch T069 Ambergate T056 Amberley T186 Amersham T114 Ammanford T129 Ancaster T019 Anderston T225, T226 Andover T160 Anerley T177, T178 Angmering T186, T188 Annan T216 Anniesland T226, T232 Ansdell & Fairhaven T097 Apperley Bridge T036, T037 Appleby T042 Appledore (kent) T192 Appleford T116 Appley Bridge T082 Apsley T066 Arbroath T026, T051, T229 Ardgay T239 Ardlui T227 Ardrossan Harbour T221 Ardrossan South Beach T221 -

Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Greater Manchester

Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Greater Manchester Sub-Regional Assessment Appendix B – Supporting Information “Living Document” June 2008 Association of Greater Manchester Authorities SFRA – Sub-Regional Assessment Revision Schedule Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Greater Manchester June 2008 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 August 2007 DRAFT Michael Timmins Jon Robinson David Dales Principal Flood Risk Associate Director Specialist Peter Morgan Alan Houghton Planner Head of Planning North West 02 December DRAFT FINAL Michael Timmins Jon Robinson David Dales 2007 Principal Flood Risk Associate Director Specialist Peter Morgan Alan Houghton Planner Head of Planning North West 03 June 2008 FINAL Michael Timmins Jon Robinson David Dales Principal Flood Risk Associate Director Specialist Anita Longworth Alan Houghton Principal Planner Head of Planning North West Scott Wilson St James's Buildings, Oxford Street, Manchester, This document has been prepared in accordance with the scope of Scott Wilson's M1 6EF, appointment with its client and is subject to the terms of that appointment. It is addressed to and for the sole and confidential use and reliance of Scott Wilson's client. Scott Wilson United Kingdom accepts no liability for any use of this document other than by its client and only for the purposes for which it was prepared and provided. No person other than the client may copy (in whole or in part) use or rely on the contents of this document, without the prior written permission of the Company Secretary of Scott Wilson Ltd. Any advice, opinions, Tel: +44 (0)161 236 8655 or recommendations within this document should be read and relied upon only in the context of the document as a whole. -

257 London Gangs Original Content Compiled by Scotland Yard's

257 London Gangs Original content compiled by Scotland Yard’s Special Crime Directorate. 1st Printed Evening Standard newspaper (London, UK), Friday 24th August 2007 Original content compiled by Scotland Yard’s Special Crime Directorate. 1st Printed Evening Standard newspaper (London, UK), Friday 24th August 2007 This document has been prepared by the Hogarth Blake editorial team for educational & reference purposes only. Listings may have changed since original print. Original content © Associated Newspapers Ltd www.hh-bb.com 1 [email protected] 257 London Gangs Original content compiled by Scotland Yard’s Special Crime Directorate. 1st Printed Evening Standard newspaper (London, UK), Friday 24th August 2007 1. Brent Church Road Thugs - Cricklewood (SLK) - Thugs of Stone Bridge - Acorn Man Dem - Walthamstow / DMX - NW Untouchable - SK Hood - Church Road Man Dem - St. Ralph’s Soldiers - Greenhill Yout Dem - Out To Terrorise (OTT) - Harsh-Don Man Dem - 9 Mill Kids (9MK) - Shakespear Youts - Westside / Red Crew - Ministry of Darkness - Willesden Green Boys - Araly Yardies - Lock City - The Copeland Boys - Mus Luv - GP Crew (Grahame Park) 2. West London Westbourne Park Man Dem - South Acton Boys - Queen Caroline Estate - Ladbroke Grove Man Dem - Latimer Road Man Dem - Queens Park Man Dem - Edwardes Wood Boys - Bush Man Dem - Becklow Man Dem - West Kensington Estate - Cromer Street Boys - Bhatts - Kanaks - Holy Smokes - Tooti Nungs - MDP (Murder Dem Pussies) - DGD (Deadly Gash Dem) 3. Camden Born Sick Crew - Centric Gang - Cromer Street Massive - Denton Boys - Drummond Street Posse - NW1 Boyz (Combo Gang) - Peckwater Gang - WC1 gang 4. Enfield N9 Chopsticks Gang - Red Brick Gang - Shanksville (aka Tanners End Lane Gang) - Little Devils - Northside Chuggy Chix - Chosen Soldiers - South Man Syndicate - Boydems Most Wanted - EMD Enfield Boys - TFA Tottenham Boys - Tiverton Boys 5. -

NOTICE of ELECTION Trafford Council Election of District Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION Trafford Council Election of District Councillors for the Wards listed below Number of Number of District District Wards Wards Councillors to Councillors to be elected be elected Altrincham One Hale Barns One Ashton Upon Mersey One Hale Central One Bowdon Two Longford Two Broadheath One Priory Two Brooklands One Sale Moor One Bucklow-St Martins One St Mary's One Clifford One Stretford One Davyhulme East One Timperley One Davyhulme West One Urmston One Flixton Two Village One Gorse Hill One 1. Nomination papers for this election can be downloaded from the Electoral Commission website or may be obtained from the Returning Officer at Room SF.241, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH, who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Completed nomination papers must be delivered by hand to the Returning Officer, Committee Room 1 Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH, on any weekday (Monday to Friday inclusive (excluding bank and public holidays)) after the date of this notice on between 10am and 4pm but no later than 4pm on Thursday 8 April 2021. 3. If any election is contested the poll will take place on Thursday 6 May 2021. 4. Applications to register to vote at this election must reach the Electoral Registration Officer by 12 midnight on Monday 19 April 2021.Applications may be made online: www.gov.uk/register to vote or sent directly to the Electoral Registration Officer at Room SF.241, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH. -

MOSSLEY STALYBRIDGE Broadbottom Hollingworth

Tameside.qxp_Tameside 08/07/2019 12:00 Page 1 P 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ST MA A 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Lydgate 0 D GI RY'S R S S D 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 A BB RIV K T O E L 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 8 9 SY C R C KES L A O 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 E 8 8 . N Y LAN IT L E E C 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 L 3 3 RN M . HO K R MANCHESTE Hollins 404T000 D R ROAD The Rough 404000 P A A E O Dacres O N HOLM R FIRTH ROAD R A T L E E R D D ANE L N L I KIL O BAN LD O N K O S LAN A A E H R Waterside D - L I E E Slate - Z V T L E D I I L A R R A E Pit Moss F O W R W D U S Y E N E L R D C S A E S D Dove Stone R O Reservoir L M A N E D Q OA R R U E I T C S K E H R C Saddleworth O IN N SPR G A V A A M Moor D M L D I E L A L Quick V O D I R E R Roaches E W I Lower Hollins Plantation E V V I G E R D D E K S C D I N T T U A Q C C L I I R NE R R O A L L Greave T O E T E TAK Dove Stone E M S IN S S I I Quick Edge R Moss D D O A LOWER HEY LA. -

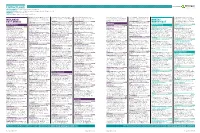

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in Planning up to Detailed Plans Submitted

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in planning up to detailed plans submitted. PLANS APPROVED Projects where the detailed plans have been approved but are still at pre-tender stage. TENDERS Projects that are at the tender stage CONTRACTS Approved projects at main contract awarded stage. Client: Sun Glow Power Agent: Green Energy - 47 Water Street, The Jewellery Quarter, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, Da Cruz Architects, 11 Tenby Street, (Central), Marriott House, Abbeyfield Road, Detailed Plans Submitted for 14 houses UK Direct Ltd, Media House, Adlington Park, Birmingham, West Midlands, B3 1HP Tel: 0121 Arnold Lodge, Cordelia Close, Leicester, LE5 Birmingham, West Midlands, B1 3AJ Tender Lenton Lane Industrial Estate, Nottingham, Client: Geffen Construction Limited Agent: MIDLANDS/ Macclesfield, Cheshire, SK10 4PZ Tel: 01625 212 9615 0LE Tel: 0116 2077700 return date: 13th September 2013 Tel: 0121 NG7 2SZ Tel: 0115 986 8856 NORTH/ Geffen Construction Limited, 2 Dalby Court, 858347 WALSALL £9.2M NORTHAMPTON £0.27M 200 1072 LOUGHBOROUGH £2M Coulby Newham, Middlesbrough, Cleveland, EAST ANGLIA LEICESTER £0.8M Land At, Landywood Lane Cheslyn Hay 74 Wellingborough Road Beacon Road Playing Field, Off Forest NORTH-EAST TS8 0XE Tel: 01642 579700 Yeoman Lane Leicester, Yeoman Street Planning authority: South Staffordshire Job: Planning authority: Northampton Job: Contracts Road THIRSK £1.3M Early Planning Planning authority: Leicester Job: Outline Outline Plans Submitted for 141 residential Detail Plans Granted for 5 flats & 1 retail unit BIRMINGHAM £4.224M Planning authority: Charnwood Job: Detail Early Planning Thirsk Community Primary Schoo, BIRMINGHAM £1.8M Plans Granted for 11 flats Client: Edelman units, 1 health centre & 1 care home Client: (new/extension) Client: Mr.