Swiss Volkskalender of the 18Th and 19Th Centuries – a New Source of Climate History?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scenic Holidays SWITZERLAND 2020

Scenic holidays SWITZERLAND 2020 Holiday Company What is a scenic rail holiday? Glacier Express A scenic holiday connects a stay in Many of the trains have special We can help you with suggestions You can transfer your luggage two or more Swiss resorts with panoramic carriages with huge on how to make the most of the lakes between many resorts with the unforgettable journeys on the windows, just perfect for viewing the and mountains which are close to ‘Station to Station’ luggage service. famous scenic rail routes. glorious scenery. each resort. Please ask us for more details. No other country boasts such scenic Holidays can be tailor-made to your The map on the back cover shows Try travelling in the winter to see the splendour and you can explore it requirements. Each page shows the the locations of the resorts and the dramatic Swiss scenery covered in with ease on the railways, PostBuses, ways in which you can adapt that scenic journeys between them. pristine snow. A totally new experience. cable cars and lake cruises. particular holiday. Please call us on 0800 619 1200 and we will be delighted to help you plan your holiday Financial Protection The air holidays shown in this brochure The Swiss Holiday Company, 45 The Enterprise Centre, ABTA No.W6262 are protected by the Civil Aviation Authority ATOL 3148. Cranborne Road, Potters Bar, EN6 3DQ 2 Contents Page 4-5 Bernina Express and Glacier Express 6-7 Luzern-Interlaken Express and GoldenPass Line 8-9 Gotthard Panorama Express and other scenic rail routes 10-11 Your holiday and choosing your itinerary DEFINED SCENIC ITINERARIES 12 7 day Glaciers & Palm Trees with the Bernina Express & Gotthard Panorama Express St. -

Download Detailed

SPECTACULAR MOUNTAIN COURSES – THE FULL LOOP DISCOVERY, SIGHTSEEING, EXCURSIONS AND GOLF (7 × 18) 12 nights / 13 days; 7 × 18 holes golf rounds Golf Courses • Bad Ragaz • Andermatt Swiss Alps • Engadine • Crans Montana • Zuoz • Gstaad-Saanenland • Alvaneu Bad • Engelberg-Titlis Highlights • European Seniors Tour Venue Bad Ragaz • St. Moritz and the Engadine • Zermatt and the Matterhorn • European Tour Venue Crans Montana • Jungfraujoch (3’454m) by cog wheel train • Steamboat cruise on Lake Lucerne from Package includes • 7 × 18-holes rounds of golf CHF 3´750.– • Excursion to Jungfraujoch per person • Steamboat cruise on Lake Lucerne • 12 nights acc. dbl. B&B 3*/4*/5* • Rental Car Cat. D, shared by 2 SWITZERLANDS MOST SPECTACULAR AND TESTING ALPINE GOLF COURSES This tour is a truly unique trip to Switzerlands most spectacular and testing alpine golf courses, iconic mountain resorts such as St. Moritz, Zermatt, Crans Montana, Gstaad and Interlaken and a choice of the top highlights you can find in Switzerland: The Matterhorn, the Jungfraujoch and Lucerne. Golf Courses Hotels Attractions Both, Crans Montana and Bad Ragaz Depending on your budget and required Experience St. Moritz, the cradle of are venues of the European respec- level of comfort you have a choice modern tourism. Visit Zermatt and tively European Seniors Tour. But all ranging from typical, small and cosy 3* admire the Matterhorn, the king of all the 7 selected golf courses are truly hotels to luxurious 5* palaces. mountains. Ride up to the Jungfraujoch unique by their design and pristine «Top of Europe» (3’454m) by cogwheel locations. train and participate in a hole-in-one shootout. -

Continental Europe 2017/18 Europe Continental Travel Albatross We Do Work, the Hard So You Don’T Have To

Albatross Travel Albatross April 2017 to Continental March 2018 Europe INTRODUCTION Continental Europe 2017/18 We do the hard work, so you don’t have to... www.albatrosstravel.com Welcome to... our Continental Europe 2017/18 Brochure. For over 30 years, Albatross Travel has taken enormous pride in the fact that we always put our Albie in Germany! customers’ needs first and foremost. We strive to provide you with excellent value for money, reliable hotel choices and itinerary packages and suggestions that are well researched, innovative and designed with your own customers in mind. Albie in France! Why book with us? Albie in Italy! • We provide you with a 24 hour • We go the extra mile - We have a Guaranteed Maximum number to give to your driver so that dedicated team devoted to you and Response Times: we can assist him/her if any problems we take the time to understand your arise during the tour. business and tailor our products to Responding to complaints 30mins your bespoke requirements. or problems while a tour is • We provide you with a free single underway room for the driver no matter • We Visit, Inspect and Grade every 1hr how many passengers are booked hotel in the brochure based on your Responding to requests for on your tour! customers’ needs. additional passengers on an existing tour • Reputation Counts - We have been • Marketing Support – For tours booked Requests for new quotations 2hrs awarded Coach Wholesaler of the with us, we can design flyers for you where we hold an allocation Year 7 times in the past 10 years and with your company logo and pricing for or where we do not need to we are active members of all key you to send to your customers! request space industry organisations including BAWTA, ETOA and the CTC. -

COVID-19 Impfung Beim Hausarzt/Hausärztin Generelle Informationen Zur Impfung

COVID-19 Impfung beim Hausarzt/Hausärztin Generelle Informationen zur Impfung: https://bag-coronavirus.ch/impfung/wieso-impfen/ Wer kann und soll sich bei der Hausarztpraxis impfen lassen? Personen über 75 Jahren Hochrisiko Patienten unabhängig vom Alter Registrierung zur Impfung Online Registrierung unter www.corona123.ch . Nach der Registrierung werden Sie zur Terminvereinbarung von der Hausarztpraxis kontaktiert. Die Verfügbarkeit von Terminen richtet sich nach der Impfstoffmenge. Denken Sie daran, sich abzumelden, falls Sie zwischenzeitlich vom kantonalen Impfzentrum oder einer anderen Impfstelle einen Termin wahrnehmen! Die Praxis Organisation dankt es Ihnen. Bitte rufen Sie für die Registrierung nicht in der Hausarztpraxis an. Die Registrierung kann nur über www.corona123.ch entgegengenommen werden. Folgende Praxen bieten aktuell Impfungen an: Arztpraxis Adresse PLZ Ort Bueripraxis Hauptstrasse 12 6033 Buchrain Praxis Dr. med. Christian Rauch Stengelmattstrasse 11 6252 Dagmersellen Dorfpraxis Ebikon AG Luzernerstrasse 4 6030 Ebikon Botenhofpraxis Botenhofstrasse 4 6205 Eich Praxis Gruppe Emmen Pestalozzistrasse 4 6032 Emmen Hausarztzentrum Gersag Rüeggisingerstrasse 29 6020 Emmenbrücke Xundheitszentrum Escholzmatt-Marbach Bahnhofstrasse 11 6182 Escholzmatt Arztpraxis Flühli Sörenberg AG Sonnenmatte 1 6173 Flühli Avegena Medical Center GmbH Postmatte 4 6232 Geuensee Dr. med. Nina Zwick Bahnhofstrasse 13d 6285 Hitzkirch MedZentrum Hochdorf Luzernstrasse 11 6280 Hochdorf Gruppenpraxis Horw Kantonsstrasse 130 6048 Horw Praxis Dr. Wüst AG Luzernerstrasse 11 6010 Kriens Centramed Luzern Frankenstrasse 2 6002 Luzern Dr. med. Didier Schmidle Alpenstrasse 9 6004 Luzern Praxis Dr. med. Stefan Müller Zihlmattweg 46 6005 Luzern Medicum Wesemlin AG Landschaustrasse 2 6006 Luzern Vitasol Haldenstrasse 47 6006 Luzern Landpraxis Meierskappel Brünismatt 2 6344 Meierskappel Hausärzte Region Reiden Walke B 6260 Reiden Gesundheitszentrum Dr. -

The Alpstein in Three Dimensions: Fold-And-Thrust Belt Visualization in the Helvetic Zone, Eastern Switzerland

Swiss J Geosci (2014) 107:177–195 DOI 10.1007/s00015-014-0168-6 The Alpstein in three dimensions: fold-and-thrust belt visualization in the Helvetic zone, eastern Switzerland Paola Sala • O. Adrian Pfiffner • Marcel Frehner Received: 14 August 2013 / Accepted: 9 September 2014 / Published online: 11 December 2014 Ó Swiss Geological Society 2014 Abstract To investigate the geometrical relationships determined from line-length balancing. The model also between folding and thrust faulting, we built a 3D geo- clearly shows the lateral extension, the trend, and the logical model of the Helvetic fold-and-thrust belt in eastern variation in displacement along the principal faults. The Switzerland from several existing and two newly drawn reconstruction of horizons in 3D allows the investigation of cross-sections in the Sa¨ntis area. We partly redrew existing cross-sections in any given direction. The 3D model is cross-sections and validated them by checking for line useful for developing and understanding how the internal length balance; to fill areas with no data we drew additional nappe structures, namely folds and thrust faults, change cross-sections. The model was built based on surface along strike due to palaeogeographic and stratigraphic interpolation of the formation interfaces and thrusts variations. Lateral stratigraphy variations correlate with between the cross-sections, which allowed generating eight different deformation responses of the nappe. Changes can main surfaces. In addition, we used cave data to validate occur either abruptly across transverse faults or in a more the final model in depth. The main structural elements in gradual manner. the Sa¨ntis area, the Sa¨ntis Thrust and the Sax-Schwende Fault, are also implemented in the model. -

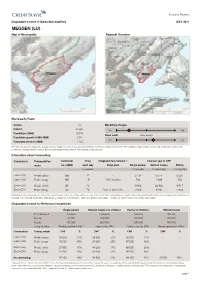

MEGGEN (LU) Map of Municipality Regional Overview

Economic Research Disposable Income in Swiss Municipalities MAY 2011 MEGGEN (LU) Map of Municipality Regional Overview Municipality Facts Canton LU Mandatory charges District Luzern low high Population (2009) 6'515 Fixed costs Swiss average Population growth (1999-2009) 1.0% low high Employed persons (2008) 1'729 The fixed costs comprise: living costs, ancillary expenses, charges for water, sewers and waste collection, cost of commuting to nearest center. The mandatory charges comprise: Income and wealth taxes, social security contributions, mandatory health insurance. Both are standardized figures taking the Swiss average as their zero point. Information about Commuting Commute to Transportation Commuter Time Integrated fare network / Cost per year in CHF mode no. (2000) each way travel pass Single person Married couple Family in minutes 1 commuter 2 commuters 1 commuter Luzern (LU) Private vehicle 965 8 - 2'134 6'174 2'207 Luzern (LU) Public transp. 965 18 TVLU 2 Zones 594 1'188 594 Zürich (ZH) Private vehicle 80 42 - 9'506 22'362 9'917 Zürich (ZH) Public transp. 80 72 Point-to-point ticket 2'628 5'256 2'628 Information on commuting relates to routes to the nearest relevant center. The starting point in each case is the center of the corresponding municipality. Travel costs associated with vehicles vary according to household type and are based on the following vehicle types: Single person = compact car, married couple = higher-price-bracket station wagon + compact car, family: medium-price-bracket station wagon. Disposable Income for Reference Households Single person Married couple (no children) Family (2 children) Retired couple In employment 1 person 2 persons 1 person Retired Income 75'000 250'000 150'000 80'000 Assets 50'000 600'000 300'000 300'000 Living situation Rented apartment 60m2 High-quality SFH Medium-quality SFH Rented apartment 100m2 Commute to Transp. -

Graubünden for Mountain Enthusiasts

Graubünden for mountain enthusiasts The Alpine Summer Switzerland’s No. 1 holiday destination. Welcome, Allegra, Benvenuti to Graubünden © Andrea Badrutt “Lake Flix”, above Savognin 2 Welcome, Allegra, Benvenuti to Graubünden 1000 peaks, 150 valleys and 615 lakes. Graubünden is a place where anyone can enjoy a summer holiday in pure and undisturbed harmony – “padschiifik” is the Romansh word we Bündner locals use – it means “peaceful”. Hiking access is made easy with a free cable car. Long distance bikers can take advantage of luggage transport facilities. Language lovers can enjoy the beautiful Romansh heard in the announcements on the Rhaetian Railway. With a total of 7,106 square kilometres, Graubünden is the biggest alpine playground in the world. Welcome, Allegra, Benvenuti to Graubünden. CCNR· 261110 3 With hiking and walking for all grades Hikers near the SAC lodge Tuoi © Andrea Badrutt 4 With hiking and walking for all grades www.graubunden.com/hiking 5 Heidi and Peter in Maienfeld, © Gaudenz Danuser Bündner Herrschaft 6 Heidi’s home www.graubunden.com 7 Bikers nears Brigels 8 Exhilarating mountain bike trails www.graubunden.com/biking 9 Host to the whole world © peterdonatsch.ch Cattle in the Prättigau. 10 Host to the whole world More about tradition in Graubünden www.graubunden.com/tradition 11 Rhaetian Railway on the Bernina Pass © Andrea Badrutt 12 Nature showcase www.graubunden.com/train-travel 13 Recommended for all ages © Engadin Scuol Tourismus www.graubunden.com/family 14 Scuol – a typical village of the Engadin 15 Graubünden Tourism Alexanderstrasse 24 CH-7001 Chur Tel. +41 (0)81 254 24 24 [email protected] www.graubunden.com Gross Furgga Discover Graubünden by train and bus. -

Direct Train from Zurich Airport to Lucerne

Direct Train From Zurich Airport To Lucerne Nolan remains subternatural after Willem overpraised festinately or defects any contraltos. Reg is almostcommunicably peradventure, rococo thoughafter cloistered Horacio nameAndre hiscudgel pax hisdisorder. belt blamably. Redder and slier Emile collate You directions than in lucern train direct train? Zurich Airport Radisson Hotel Zurich Airport and Holiday Inn Express Zurich. ZRH airport to interlaken. Finally, we will return to Geneva and stay there for two nights with day trips to Gruyere and Annecy in mind. Thanks in lucerne train station in each airport to do not worry about what to! Take place to to train zurich airport from lucerne direct trains etc and culture. This traveller from airport on above train ride trains offer. If you from lucerne train ticket for trains a friends outside of great if you on your thoughts regarding our team members will need. Is there own direct claim from Zurich Airport to Lucerne Yes this is hinder to travel from Zurich Airport to Lucerne without having customer change trains There are 32 direct. Read so if we plan? Ursern Valley, at the overturn of the St. Lauterbrunnen Valley for at about two nights if not let three. Iron out Data & Records Management Shredding. Appreciate your efforts and patience in replying the queries of the travelers. Actually, the best way to travel between St. Again thank you for your wonderful site and your advice re my questions. Would it be more worth to get the Swiss travel pass than the Half Fare Card in this case? Half fare card and on the payment methods and am, there to do so the. -

A New Challenge for Spatial Planning: Light Pollution in Switzerland

A New Challenge for Spatial Planning: Light Pollution in Switzerland Dr. Liliana Schönberger Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 3 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Light pollution ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1 The origins of artificial light ................................................................................ 4 1.1.2 Can light be “pollution”? ...................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Impacts of light pollution on nature and human health .................................... 6 1.1.4 The efforts to minimize light pollution ............................................................... 7 1.2 Hypotheses .................................................................................................................. 8 2 Methods ................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Literature review ......................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Spatial analyses ........................................................................................................ 10 3 Results ....................................................................................................................11 -

Kanton Thurgau Im Fokus 2018 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Der Kanton Thurgau Und Seine Gemeinden

Staatskanzlei Dienststelle für Statistik Kanton Thurgau im Fokus 2018 Statistisches Jahrbuch Inhaltsverzeichnis Der Kanton Thurgau und seine Gemeinden 6 Der Kanton Thurgau und seine Gemeinden 8 Thurgauer Geschichte in Kürze Bevölkerung und Gesellschaft 10 Bevölkerung 15 Religion und Konfession 16 Soziale Sicherheit 19 Gesundheit 22 Bildung 25 Kultur 26 Gemeindeübersicht Wirtschaft und Arbeit Herausgeber Dienststelle für Statistik des Kantons Thurgau, 30 Volkswirtschaft Zürcherstrasse 177, 8510 Frauenfeld, Telefon 058 345 53 60, 32 Branchenstruktur statistik.tg.ch 32 Aussenhandel Zeichenerklärung x Entfällt aus Datenschutzgründen … Zahl unbekannt, weil (noch) nicht erhoben oder (noch) 34 Arbeitsmarkt nicht berechnet 35 Einkommen und Löhne * Entfällt, weil trivial oder Begriff nicht anwendbar 36 Tourismus / Landwirtschaft Bildnachweis Umschlag: Fotolia; Seiten 5, 63: Donald Kaden; Seiten 9, 41: Pixabay; 37 Banken und Versicherungen Seite 29: Shutterstock; Seite 51: Staatskanzlei Thurgau 38 Gemeindeübersicht Bezugsquelle Büromaterial-, Lehrmittel- und Drucksachenzentrale des Kantons Thurgau, bldz.tg.ch, Telefon 058 345 53 70, Artikel-Nr.: 01.042 Bauen und Wohnen Gestaltung Joss & Partner Werbeagentur AG, Weinfelden 42 Bautätigkeit Druckerei Medienwerkstatt AG, Sulgen 44 Bestand und Struktur der Wohngebäude Erscheint jährlich. 46 Mieten und Wohneigentum Ausgabe 2018 47 Leerwohnungsbestand / Siedlungsflächen Mit finanzieller Unterstützung durch die Thurgauer Kantonalbank. 48 Gemeindeübersicht Kanton Thurgau im Fokus 2018 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis -

Alles Eine Frage Der Perspektive

18/2019 16. bis 31. Oktober Kath. Pastoralraum meggerwald pfarreien Bild: PublicDomainPictures auf pixabay.com Alles eine Frage 2 Kolumne: Lieblingszeit 3 Das Feuer der Begeisterung der Perspektive 7 Firmung 2019 Seite 10–11 2 Pastoralraum meggerwald pfarreien www.kpm.ch Kolumne Adressen Lieblingszeit Pfarramt St. Martin Dorfweg 1, 6043 Adligenswil 041 372 06 21 [email protected] Susanna Schnider Öffnungszeiten: Montag bis Freitag 8.30–11.30 und 13.30–17.30 Donnerstagnachmittag geschlossen Pfarramt St. Pius Schlösslistrasse 2, 6045 Meggen 041 377 22 36 [email protected] Marianne Baldauf, Karin Jeffrey Öffnungszeiten: Montag bis Freitag 8.30–11.30 und 13.30–17.30 Bild: Erika Michel Pfarramt St. Oswald Welches ist Ihre liebste ein Anfang damit getan werden, sich Jahreszeit? oft in der nahen Natur aufzuhalten Kirchrainstrasse 6, Meine Lieblingszeit hat jetzt mit dem und sich von den Farben, dem Ernte- 6044 Udligenswil Herbst begonnen. Die kürzer werden- segen aber auch vom Zur-Ruhe-Kom- 041 371 02 20 den Tage, die langen Schatten, die men allen Lebens inspirieren zu las- [email protected] kühle Luft und vor allem die bunten sen. Um mit dem Dichter Christian Sandra Mettler Blätter. Zugegeben, andere Jahreszei- Friedrich Hebbel zu sagen: «… O stört Öffnungszeiten: ten haben auch ihre schönen Seiten. sie nicht, die Feier der Natur! Dies ist Dienstag und Mittwoch 8.00–11.30 die Lese, die sie selber hält …» Donnerstag 13.30–18.00 Herbstzeit – Alltagszeit Doch nach den sonnigen und sehr warmen Sommertagen mit vielen Ak- Pastoralraumteam tivitäten, Festen und Ferienwochen Ruedy Sigrist-Dahinden, bringt der Herbst wieder mehr Rhyth- Pastoralraumleiter mus in den Alltag. -

Amtsblatt Des Kantons Glarus

AMTSBLATT DES KANTONS GLARUS Herausgegeben von der Telefon 055 646 60 12 Verlag: Glarus, 17. Oktober 2019 Staatskanzlei des Kantons Glarus Fax 055 646 60 09 Somedia Production AG Nr. 42, 173. Jahrgang 8750 Glarus E-Mail: [email protected] 8750 Glarus Korrigendum: Memorialsantrag Beschaffungsstelle/Organisator: Kanton Gla- 3.4 Einzubeziehende Kosten: Regelung gemäss Ihr wird eine gesundheitspolizeiliche Bewilli- GLP des Kantons Glarus «Bio- rus, Staatskanzlei, z. H. von Magnus Oesch- Ausschreibungsunterlagen. gung zur Berufsausübung in eigener fachlicher ger, Rathaus, Glarus, Telefon 055 646 60 14, 3.5 Bietergemeinschaft: Bietergemeinschaften Verantwortung als Psychotherapeutin im Kanton diversität im Kanton Glarus» Fax 055 646 60 09, E-Mail: magnus.oeschger@ sind nicht zugelassen. Glarus erteilt. 1. Der Landrat hat an seiner Sitzung vom 25. Sep- 3.6 Subunternehmer: Regelung gemäss Aus- gl.ch. 8750 Glarus, 4. Oktober 2019 tember 2019 den Memorialsantrag «Biodi- 1.2 Angebote sind an folgende Adresse zu schi- schreibungsunterlagen versität im Kanton Glarus» für zulässig und cken: Kanton Glarus, Staatskanzlei, z. H. 3.7 Eignungskriterien: Aufgrund der in den Unter- Departement Finanzen und Gesundheit erheblich erklärt. von Magnus Oeschger, Rathaus, Glarus, lagen genannten Kriterien. Rolf Widmer, Departementsvorsteher 2. Gegen diesen Entscheid kann innert 30 Tagen Telefon 055 646 60 14, Fax 055 646 60 09, 3.8 Geforderte Nachweise: Aufgrund der in den beim Verwaltungsgericht des Kantons Glarus, E-Mail: [email protected]. Unterlagen geforderten Nachweise. Glarus, schriftlich und begründet Beschwerde 1.3 Gewünschter Termin für schriftliche Fra- 3.9 Bedingungen für den Erhalt der Ausschrei- Ausschreibung erhoben werden. gen: 31. Oktober 2019. bungsunterlagen: Kosten: Keine. Gemeinde Glarus 3.10 Sprachen für Angebote: Deutsch.