Oral Mosapride Can Provide Additional Anti-Emetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Developments in Prokinetic Therapy for Gastric Motility Disorders

REVIEW published: 24 August 2021 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.711500 New Developments in Prokinetic Therapy for Gastric Motility Disorders Michael Camilleri* and Jessica Atieh Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States Prokinetic agents amplify and coordinate the gastrointestinal muscular contractions to facilitate the transit of intra-luminal content. Following the institution of dietary recommendations, prokinetics are the first medications whose goal is to improve gastric emptying and relieve symptoms of gastroparesis. The recommended use of metoclopramide, the only currently approved medication for gastroparesis in the United States, is for a duration of less than 3 months, due to the risk of reversible or irreversible extrapyramidal tremors. Domperidone, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, is available for prescription through the FDA’s program for Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs. Macrolides are used off label and are associated with tachyphylaxis and variable duration of efficacy. Aprepitant relieves some symptoms of gastroparesis. There are newer agents in the pipeline targeting diverse gastric (fundic, antral and pyloric) motor functions, including novel serotonergic 5-HT4 agonists, dopaminergic D2/3 antagonists, neurokinin NK1 antagonists, and ghrelin agonist. Novel Edited by: targets with potential to improve gastric motor functions include the pylorus, macrophage/ Jan Tack, inflammatory function, oxidative -

Prokinetics and Ghrelin for the Management of Cancer Cachexia Syndrome

85 Review Article Prokinetics and ghrelin for the management of cancer cachexia syndrome Jimi S. Malik, Sriram Yennurajalingam Department of Palliative Care, Rehabilitation and Integrative Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: S Yennurajalingam; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: S Yennurajalingam; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Sriram Yennurajalingam, MD. Department of Palliative Care, Rehabilitation, and Integrative Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd., Unit 1414, Houston, TX 77030, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Cancer cachexia (CC) is one of the most distressing syndromes for both patients and their families. CC can have an impact on patient reported quality of life and overall survival. It is often associated with symptoms such as fatigue, depressed mood, early satiety, and anorexia. Prokinetic agents have been found to improve chronic nausea and early satiety associated with CC. Among the prokinetic agents, metoclopramide is one of the best studied medications. The role of the other prokinetic agents, such as domperidone, erythromycin, haloperidol, levosulpiride, tegaserod, cisapride, mosapride, renzapride, and prucalopride is unclear for use in cachectic cancer patients due to their side effect profile and limited efficacy studies in cancer patients. There has been an increased interest in the use of ghrelin-receptor agonists for the treatment of CC. Anamorelin HCl is a highly selective, novel ghrelin receptor agonist. -

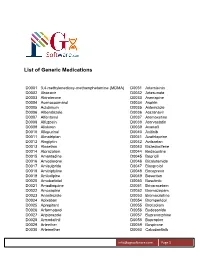

List of Generic Medications

List of Generic Medications D0001 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) D0031 Artemisinin D0002 Abacavir D0032 Artesunate D0003 Abiraterone D0033 Asenapine D0004 Acenocoumarol D0034 Aspirin D0005 Aclidinium D0035 Astemizole D0006 Albendazole D0036 Atazanavir D0007 Alfentanyl D0037 Atomoxetine D0008 Alfuzosin D0038 Atorvastatin D0009 Aliskiren D0039 Avanafil D0010 Allopurinol D0040 Axitinib D0011 Almotriptan D0041 Azathioprine D0012 Alogliptin D0042 Azilsartan D0013 Alosetron D0043 Bazedoxifene D0014 Alprazolam D0044 Bedaquiline D0015 Amantadine D0045 Bepridil D0016 Amiodarone D0046 Bicalutamide D0017 Amisulpride D0047 Bisoprolol D0018 Amitriptyline D0048 Boceprevir D0019 Amlodipine D0049 Bosentan D0020 Amobarbital D0050 Bosutinib D0021 Amodiaquine D0051 Brivaracetam D0022 Amoxapine D0052 Bromazepam D0023 Anastrozole D0053 Bromocriptine D0024 Apixaban D0054 Bromperidol D0025 Aprepitant D0055 Brotizolam D0026 Arformoterol D0056 Budesonide D0027 Aripiprazole D0057 Buprenorphine D0028 Armodafinil D0058 Bupropion D0029 Arteether D0059 Buspirone D0030 Artemether D0060 Cabozantinib [email protected] Page 1 List of Generic Medications D0061 Canagliflozin D0091 Clofarabine D0062 Cannabidiol (CBD) D0092 Clofibrate D0063 Cannabinol (CBN) D0093 Clomipramine D0064 Captopril D0094 Clonazepam D0065 Carbamazepine D0095 Clonidine D0066 Carisoprodol D0096 Clopidogrel D0067 Carmustine D0097 Clorazepate D0068 Carvedilol D0098 Clozapine D0069 Celecoxib D0099 Cocaine D0070 Ceritinib D0100 Codeine D0071 Cerivastatin D0101 Colchicine D0072 Cetirizine -

Gastroparesis: 2014

GASTROINTESTINAL MOTILITY AND FUNCTIONAL BOWEL DISORDERS, SERIES #1 Richard W. McCallum, MD, FACP, FRACP (Aust), FACG Status of Pharmacologic Management of Gastroparesis: 2014 Richard W. McCallum Joseph Sunny, Jr. Gastroparesis is characterized by delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction of the gastric outlet or small intestine. The main etiologies are diabetes, idiopathic and post- gastric and esophageal surgical settings. The management of gastroparesis is challenging due to a limited number of medications and patients often have symptoms, which are refractory to available medications. This article reviews current treatment options for gastroparesis including adverse events and limitations as well as future directions in pharmacologic research. INTRODUCTION astroparesis is a syndrome characterized by documented gastroparesis are increasing.2 Physicians delayed emptying of gastric contents without have both medical and surgical approaches for these Gmechanical obstruction of the stomach, pylorus or patients (See Figure 1). Medical therapy includes both small bowel. Patients can present with nausea, vomiting, prokinetics and antiemetics (See Table 1 and Table 2). postprandial fullness, early satiety, pressure, fullness The gastroparesis population will grow as diabetes and abdominal distension. In addition, abdominal pain increases and new therapies will be required. What located in the epigastrium, and distinguished from the do we know about the size of the gastroparetic term discomfort, is increasingly being recognized population? According to a study from the Mayo Clinic as an important symptom. The main etiologies of group surveying Olmsted County in Minnesota, the gastroparesis are diabetes, idiopathic, and post gastric risk of gastroparesis in Type 1 diabetes mellitus was and esophageal surgeries.1 Hospitalizations from significantly greater than for Type 2. -

A Four-Country Comparison of Healthcare Systems, Implementation

Neurogastroenterology & Motility Neurogastroenterol Motil (2014) 26, 1368–1385 doi: 10.1111/nmo.12402 REVIEW ARTICLE A four-country comparison of healthcare systems, implementation of diagnostic criteria, and treatment availability for functional gastrointestinal disorders A report of the Rome Foundation Working Team on cross-cultural, multinational research M. SCHMULSON,* E. CORAZZIARI,† U. C. GHOSHAL,‡ S.-J. MYUNG,§ C. D. GERSON,¶ E. M. M. QUIGLEY,** K.-A. GWEE†† & A. D. SPERBER‡‡ *Laboratorio de Hıgado, Pancreas y Motilidad (HIPAM)-Department of Experimental Medicine, Faculty of Medicine-Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM). Hospital General de Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico †Gastroenterologia A, Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, University La Sapienza, Rome, Italy ‡Department of Gastroenterology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Science, Lucknow, India §Department of Gastroenterology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea ¶Division of Gastroenterology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA **Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Houston Methodist Hospital and Weill Cornell Medical College, Houston, TX, USA ††Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore ‡‡Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel Key Messages • This report identified seven key issues related to healthcare provision that may impact how patients with FGIDs are investigated, diagnosed and managed. • Variations in healthcare provision around the world in patients with FGIDs have not been reviewed. • We compared four countries that are geographically and culturally diverse, and exhibit differences in the healthcare coverage provided to their population: Italy, South Korea, India and Mexico. • Since there is a paucity of publications relating to the issues covered in this report, some of the findings are based on the authors’ personal perspectives, press reports and other published sources. -

The Use of Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances

WHO/PSM/QSM/2006.3 The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances 2006 Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Quality Assurance and Safety: Medicines Medicines Policy and Standards The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Antianxiety and Antidepressive Agents for Functional Dyspepsia

doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.9099-17 Intern Med 56: 3127-3133, 2017 http://internmed.jp 【 ORIGINAL ARTICLE 】 A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Antianxiety and Antidepressive Agents for Functional Dyspepsia Mariko Hojo 1, Akihito Nagahara 2, Daisuke Asaoka 1, Yuji Shimada 2, Hitoshi Sasaki 3, Kohei Matsumoto 1, Tsutomu Takeda 1, Hiroya Ueyama 1, Kenshi Matsumoto 1 and Sumio Watanabe 1 Abstract: Objective Functional dyspepsia (FD) is defined as persistent or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen without organic disease. Psychosocial factors have been proposed as an important element in the pathophysiology of FD. Therefore, psychotropic agents having antianxiety or antidepressive action are ex- pected to alleviate FD. We previously reported on the treatment of FD using such agents in a systematic re- view, wherein the effectiveness of the agents on FD was suggested, although there were several limitations. We searched for articles on this subject after our systematic review and re-reviewed them systematically. Methods Articles were searched for in MEDLINE from 2003 to 2014 using terms related to antianxiety or antidepressive agents. Clinical studies in which the effectiveness of such agents was clearly stated were se- lected from the retrieved articles. The newly selected and previously selected studies were combined, and sta- tistical analyses were carried out. Results Nine studies were selected. Five of the studies indicated a significant symptomatic improvement us- ing psychotropic drugs. A statistical analysis suggested a significant treatment effect of psychotropic agents having antianxiety or antidepressive action [pooled relative risk (PRR), 0.72; 95% confidence interval (95% CI), 0.52-0.99; p=0.0406] but did not show a significant benefit of treatment with agents having an antide- pressive action alone (PRR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.38-1.03; p=0.0665). -

Surveillance Review Proposal PDF 387 KB

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Surveillance programme Surveillance proposal consultation document Irritable bowel syndrome NICE guideline CG61 – 8-year surveillance review Background information Guideline issue date: February 2008 3-year review (no update)* 6-year review (yes to update) *Although the 3-year review decision was no update, the findings were subsequently used to pilot the NICE’s rapid update process. Surveillance proposal for consultation We will not update the guideline at this time. Reason for the proposal New evidence We found 105 new studies in a search for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews published between 01 September 2013 and 18 July 2016. We also considered studies identified by members of the guideline committee who originally worked on this guideline. Evidence identified in previous surveillance 3 years and 6 years after publication of the guideline was also considered. This included 52 studies identified by search. From all sources, 157 studies were considered to be relevant to the guideline. Surveillance proposal consultation document for Irritable bowel syndrome (2008) NICE guideline CG61 1 of 44 This included new evidence that is consistent with current recommendations on: diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) dietary interventions physical activity interventions drug treatments (antispasmodics, laxatives, anti-motility agents and antidepressants) psychotherapy hypnotherapy, biofeedback and relaxation therapy acupuncture and patient information. We also identified new evidence in the following areas that was inconsistent with, or not covered by, current recommendations, but the evidence was not considered to impact on the guideline: ondansetron vitamin D supplementation herbal medicines. We did not find any new evidence on reflexology, psychosocial interventions, or self-help and support groups. -

Prokinetics for the Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia: Bayesian

Yang et al. BMC Gastroenterology (2017) 17:83 DOI 10.1186/s12876-017-0639-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prokinetics for the treatment of functional dyspepsia: Bayesian network meta-analysis Young Joo Yang, Chang Seok Bang* , Gwang Ho Baik, Tae Young Park, Suk Pyo Shin, Ki Tae Suk and Dong Joon Kim Abstract Background: Controversies persist regarding the effect of prokinetics for the treatment of functional dyspepsia (FD). This study aimed to assess the comparative efficacy of prokinetic agents for the treatment of FD. Methods: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of prokinetics for the treatment of FD were identified from core databases. Symptom response rates were extracted and analyzed using odds ratios (ORs). A Bayesian network meta- analysis was performed using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method in WinBUGS and NetMetaXL. Results: In total, 25 RCTs, which included 4473 patients with FD who were treated with 6 different prokinetics or placebo, were identified and analyzed. Metoclopramide showed the best surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) probability (92.5%), followed by trimebutine (74.5%) and mosapride (63.3%). However, the therapeutic efficacy of metoclopramide was not significantly different from that of trimebutine (OR:1.32, 95% credible interval: 0.27–6.06), mosapride (OR: 1.99, 95% credible interval: 0.87–4.72), or domperidone (OR: 2.04, 95% credible interval: 0.92–4.60). Metoclopramide showed better efficacy than itopride (OR: 2.79, 95% credible interval: 1. 29–6.21) and acotiamide (OR: 3.07, 95% credible interval: 1.43–6.75). Domperidone (SUCRA probability 62.9%) showed better efficacy than itopride (OR: 1.37, 95% credible interval: 1.07–1.77) and acotiamide (OR: 1.51, 95% credible interval: 1.04–2.18). -

2015.09 IBS Drug Class Review.Pdf

Drug Class Review Agents Indicated in the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome 56:92 GI Drugs, Miscellaneous Alosetron (Lotronex®) Eluxadoline (Viberzi®) Linaclotide (Linzess®) Lubiprostone (Amitiza®) Tegaserod (Zelnorm®) Final Report September 2015 Review prepared by: Melissa Archer, PharmD, Clinical Pharmacist Irene Pan, PharmD Candidate 2016 Chelsey Hancock, PharmD Candidate 2016 Carin Steinvoort, PharmD, Clinical Pharmacist Gary Oderda, PharmD, MPH, Professor University of Utah College of Pharmacy Copyright © 2015 by University of Utah College of Pharmacy Salt Lake City, Utah. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 1. Comparison of the Agents Indicated in the Treatment of IBS ................................. 5 Disease Overview ........................................................................................................................ 6 Table 2. Summary of IBS Treatment Options ........................................................................ 8 Table 3. IBS Disease Staging System .................................................................................... 11 Table 4. Most Current Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of IBS ..................... 13 Pharmacology .............................................................................................................................. -

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information No

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information No. 260 August 2009 Table of Contents 1. Tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants, associated with aggression ................................................................................................... 3 2. Important Safety Information .................................................................. 9 .1. Telmisartan ··························································································· 9 .2. Phenytoin, Phenytoin/Phenobarbital, Phenytoin/Phenobarbital/ Caffeine and Sodium Benzoate, Phenytoin Sodium ··························· 13 3. Revision of PRECAUTIONS (No. 208) Lamotrigine (and 9 others) ············································································ 17 4. List of products subject to Early Post-marketing Phase Vigilance ..................................................... 21 This Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information (PMDSI) is issued based on safety information collected by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. It is intended to facilitate safer use of pharmaceuticals and medical devices by healthcare providers. PMDSI is available on the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency website (http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/index.html) and on the MHLW website (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/, Japanese only). Published by Translated by Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau, Office of Safety I, Ministry of -

Studies on Canine Gastric Motility Disorders and the Clinical Application of 5-HT4 Receptor Agonist Mosapride Atsushi Tsukamoto

Studies on Canine Gastric Motility Disorders and the Clinical Application of 5-HT4 Receptor Agonist Mosapride (犬の胃運動障害および 5-HT4 受容体作動薬モサプリドの臨床応用に関する研究) Atsushi Tsukamoto 塚本 篤士 1 Contents Pages General introduction - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 Chapter 1 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 Real-time Ulltrasonographic Method of Canine Gastric Motility in Postprandal State Chapter 2 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 32 Prokinetic Action of 5-HT4R Agonist Mosapride in Dog Chapter 3 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 49 Association of Gastric Motility Disorders in Adverse Drug Reaction and the Clinical Efficacy of Mosapride in Dogs 3-1 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 51 Effect of Vincristine on Canine Gastric Motility and the Prokinetic Action of Mosapride in Dogs 3-2 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 69 Anti-ulcerogenic and Prokinetic Action of Mosapride on Prednisolone-induced Gastrointestinal (GI) Adverse Effect 2 Chapter 4 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 93 Effect of Mosapride on Pro-inflammatory Cytokines Expression in Canine Primary Cultured