AQA Aos3: Music for Media Part 2 – Michael Giacchino and Nobuo Uematsu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

PRESS RELEASE Media Contact Michael Prefontaine | Silicon Studio

PRESS RELEASE Media Contact Michael Prefontaine | Silicon Studio | [email protected] |+81 (0)3 5488 7070 From Silicon Studio and MISTWALKER New game "Terra Battle 2" under joint development Teaser site, trailer, and social media released Tokyo, Japan, (June 22, 2017) –Middleware and game development company, Silicon Studio Corporation are excited to announce their joint development with renowned game developer MISTWALKER COPRPORATION, to develop the next game in the hit “Terra Battle” series, “Terra Battle 2” for smartphones and PC. The official trailer and social media sites are set to open June 22, 2017. About Terra Battle 2 The battle gameplay that wowed so many players in the original "Terra Battle" remains, but now it is complimented by a full role-playing game in which every system has evolved to deliver a more deeply enriched story and experience. The adoption of the dynamic field map allows you direct and travel with your characters throughout the world. Intense emotion abounds from fated encounters, bitter farewells, the joy of glory won, pain and heartbreak, and more heated battles that will have your hands sweating. 1 | Can the people of "Terra" ever uncover the illusive truth of their world? A spectacular journey is waiting for you. ●Gameplay screenshot(Depicted is still under development) Screenshots from left to right: Title Screen, Field Map, Battle Scene, Event Scene ●Character/ Guardian Left:Roland(Guardian)/Right:Sarah(Character) 2 | Trailer, Teaser site, Social Media Ahead of the release the teaser site, trailer, and official Twitter and Facebook accounts will open. For now, these are only available in Japanese, but users are welcome to check in for more information. -

Complete Catalogue of the Musical Themes Of

COMPLETE CATALOGUE OF THE MUSICAL THEMES OF CATALOGUE CONTENTS I. Leitmotifs (Distinctive recurring musical ideas prone to development, creating meaning, & absorbing symbolism) A. Original Trilogy A New Hope (1977) | The Empire Strikes Back (1980) | The Return of the Jedi (1983) B. Prequel Trilogy The Phantom Menace (1999) | Attack of the Clones (2002) | Revenge of the Sith (2005) C. Sequel Trilogy The Force Awakens (2015) | The Last Jedi (2017) | The Rise of Skywalker (2019) D. Anthology Films & Misc. Rogue One (2016) | Solo (2018) | Galaxy's Edge (2018) II. Non-Leitmotivic Themes A. Incidental Motifs (Musical ideas that occur in multiple cues but lack substantial development or symbolism) B. Set-Piece Themes (Distinctive musical ideas restricted to a single cue) III. Source Music (Music that is performed or heard from within the film world) IV. Thematic Relationships (Connections and similarities between separate themes and theme families) A. Associative Progressions B. Thematic Interconnections C. Thematic Transformations [ coming soon ] V. Concert Arrangements & Suites (Stand-alone pieces composed & arranged specifically by Williams for performance) A. Concert Arrangements B. End Credits VI. Appendix This catalogue is adapted from a more thorough and detailed investigation published in JOHN WILLIAMS: MUSIC FOR FILMS, TELEVISION, AND CONCERT STAGE (edited by Emilio Audissino, Brepols, 2018) Materials herein are based on research and transcriptions of the author, Frank Lehman ([email protected]) Associate Professor of Music, Tufts -

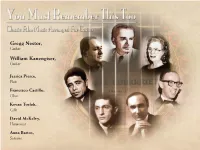

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Musikliste Zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel Sortiert in Der Reihenfolge, in Der Sie in Der Doku Zu Hören Sind

Z Musikliste zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel sortiert in der Reihenfolge, in der sie in der Doku zu hören sind. Folge 1 MUSIK - Titel CD / Interpret Composer Trailer Terra X Trailer Terra X Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Dr. Ford Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Ramin Djawadi Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Eleven Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Race To Mark's Flat Bridget Jones's Baby / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Boggis, Bunce and Fantastic Mr. Fox / Alexandre Desplat Alexandre Desplat Bean Hibernation Pod 1625 Passengers / Thomas Newman Thomas Newman Jack It Up Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Letters Theodore Shapiro Reporters Swarm Confirmation / Harry Gregson Williams Harry Gregson Williams Persistence Burnt / Rob Simonsen Rob Simonsen Introducing Howard Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Inlet Theodore Shapiro The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Theodore Shapiro Letters Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Fell Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers Me Before You Me Before You / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Orchestral This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon The Skylab Plan Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Speight Lived Here The Knick (Season 2) / Cliff Martinez Cliff Martinez This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon 3 Minutes Of Moderat A New Beginning Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers 3 Minutes Of Moderat The Walk The Walk / Alan Silvestri Alan Silvestri Dr. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

Video Game Developer Pdf, Epub, Ebook

VIDEO GAME DEVELOPER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chris Jozefowicz | 32 pages | 15 Aug 2009 | Gareth Stevens Publishing | 9781433919589 | English | none Video Game Developer PDF Book Photo Courtesy: InnerSloth. Upon its launch, Will of the Wisps made waves for frame-rate issues and bugs, but after those were quickly patched, it was easy to fall in love with every aspect of the game. Video game designers need to have analytical knowledge as well as strong creative skills. First, make sure you have a good computer with some processing power and the right software. It takes cues from choose-your-own-adventure novels as well as some of the earliest narrative-driven video games from the '70s and '80s, including the first-known work of interactive fiction, Colossal Cave Adventure. Check out the story of the whirlwind visit and hear about our first peek at the game. From its dances to its massive tournaments, Fortnite has won over gamers around the world. Are there video games designed for moms? This phase can take as many hours as the original creation of the game. In Animal Crossing , you play as a human character who moves to a new town — in the case of New Horizons , your character moves to a deserted island at the invitation of series regular Tom Nook, a raccoon "entrepreneur. One standout aspect of the game was its music. If you've ever gotten immersed in your game character's story and movements, you've probably wondered how these creations can move so fluidly. How MotionScan Technology Works Animation just keeps getting more and more realistic, as emerging technology MotionScan demonstrates quite nicely. -

Arkansas Symphony Presents Music of Star Wars with Costumes, Trivia, and Music Attendees Are Invited to Attend in Costume for a Chance to Win a Prize

PRESS RELEASE: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Brandon Dorris Office: (501)666-1761, ext. 118 Mobile: (501)650-2260 Fax: (501)666-3193 Email: [email protected] Arkansas Symphony Presents Music of Star Wars with Costumes, Trivia, and Music Attendees are invited to attend in costume for a chance to win a prize. Little Rock, ARK, September 27, 2018 - The Arkansas Symphony Orchestra, Philip Mann, Music Director and Conductor, announces a presentation of The Music of Star Wars, 7:30 p.m. Saturday, October 20th and 3:00 p.m. Sunday, October 21st at the Robinson Center. The concert will feature music selected from the entire series of 10 feature films, an animated film, three TV films, and six animated series spanning more than 40 years. The celebrated film composer John Williams (Star Wars, Jaws, Indiana Jones, Harry Potter), composed all music from the eight saga films (Williams is also slated to score the ninth and final film), with award-winners Michael Giacchino and John Powell composing the music for the spin-off films. The program will feature costumes, trivia, and decoration of the Robinson Center to create a multi- sensory experience. Audiences are invited attend this family-friendly event in costume as their favorite character. A random Star Wars-themed prize winner will be selected from costumed attendees at each performance. Tickets are on sale now and prices are $16, $36, $57, and $68 and can be purchased online at www.ArkansasSymphony.org/starwars; at the Robinson Center street-level box office beginning 90 minutes prior to a concert; or by phone at 501-666-1761, ext. -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Halloween Concert

Music Department Calendar of Events Central Washington University Department of Music presents: Halloween Concert Dr. Elioac Salokin, Director of Orchestra Dr. Raanediew Yrag, Director of Choir Asomrehalliv Nayr, Assistant Conductor Renierhcs Leinad, Assistant Conductor Jerilyn S. McIntyre Music BuildingDr. Wayne S. Hertz Concert Hall Wednesday, October 30th, 2019 7:00 PM Personnel Program FARMING FOR TREBLE CANDY HORNS SNOWWHITE AND THE March of the Goblins Adam Glaser Cow Doctor* SEVEN DWARVES SoBEEa Goodenbuzz+ Jeffrey Snow White* Chicken Leighton Dopey Jerry Snedeker Doc Lydia BoPeep Sleepy Batalip+ THE POWERPUFF GIRLS Sneezy Old McDonald / Spider Pig arr. Mike Scott Tom Blossom* Grumpy Scarecrow Buttercup^ Bashful ed. Daniel Schreiner Bubbles Happy INNER VOICES, TRULY HEROIC SCRUFFY LOOKING NERF CELLO THERE Disgruntled Food Employee HERDERS Rey*^ Choir - Ecce Vicit Leo (Double) Peter Phillips Jack and Jill Payton Luke Skywalker* Palermo Charlotte Web Leia Organa Lucy Zoboomafoo Sheev Palpatine* Ricky Spooky Stuckey+ Han Solo* Pizza Ash Ketchum Poor College Student Savurkey Gobbler+ HYDROFLASKS Lilith Star Wars - Main Title John Williams Black Hydroflask* Princess Leia FARMERS ONLY Grey Hydroflask Greg Universe Erik Green Hydroflask The Rock Kornel Blue Hydroflask Something Wicked “High Ground”+ Red Hydroflask Renaissance Lady Gus Rrr’Donnell Mystery Man Eight Laughing Voices Hyo-won Woo Earl BLACK AND WHITE ALL Musical Superhero Old McDonald OVER Carina Kanter Farmer Mike BoJack Horseman Chip ROCK BOTTOM VIOLENT Mary Poppins* THE FLOCK SHOULDER HARPS Professor Utonium The Typewriter Leroy Anderson David Baa-allard Mrs. Elizabeth Peacock*^ One Ring to Rule Them All Elambjah Bergevin Andrés de Fonollosa Medical Officer Phipps Luke Baa-cheverria Captain Long John Silver Science Officer Hoffman Tommy Marsheep Mognarktharol, the Djent Electric Blue #7 Tyler Mathewes Zombie Arwen. -

The Film Music Label Partners with the Golden State Pops Orchestra for Another 'Music of the 'Star Wars' Universe' Concert

7:20 PM PDT 6/19/2013 by Austin Siegemund-Broka The Golden State Pops Orchestra The film music label partners with the Golden State Pops Orchestra for another 'Music of the 'Star Wars' Universe' concert. Film music label Varèse Sarabande Records is celebrating its 35th anniversary at home and abroad. The Golden State Pops Orchestra’s June 15 concert Music of the 'Star Wars' Universe commemorated the milestone with a performance of Joel McNeely’s score, released on Varèse, for the 1996 multimedia project Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire, alongside pieces from John Williams’ iconic Star Wars film scores -- not released on Varèse, though the label has distributed other orchestras’ renditions of Williams’ Star Wars compositions. Hans Zimmer, Danny Elfman, Michael Giacchino, John Powell and other guest composers came out for the GSPO’s previous concert, a Varèse Sarabande 35th anniversary revue on May 11. Varèse executive producer Robert Townson, who hosted the revue, says he opted to work with the GSPO to bring Varèse’s anniversary festivities back to the label’s Los Angeles roots. “I sent an email to the conductor and said, ‘we’d like to do something locally. To be honest, your orchestra came to mind because of the attitude and the degree to which you’re making a point of celebrating the aspects of film music I really appreciate, the artistry,’” Townson says. Two more concerts will partner the GSPO with Varèse: the orchestra’s annual Halloween and winter holiday performances, held October 19 and December 21. Plans for a single revue concert grew into a yearlong Varèse celebration when GSPO conductor Steven Allen Fox realized how much Varèse-released music was already on the GSPO season’s programs.