A Case Study for the Plitvice Lakes National Park, Croatia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tourism in Croatia: Politics, Projects and Environmental Sustainability

Unofficial English version provided by the author of the Italian paper published in: BOLLETTINO DELLA SOCIETA GEOGRAFICA ITALIANA ROMA - Serie XIII, vol. VII (2014), pp. 413-433 ORNELLA ALBOLINO THE TOURISM IN CROATIA: POLITICS, PROJECTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY Abstract - The paper aims to consider the development and evolution of the tourism in Croatia and its economic and social impact. Croatia can be considered an interesting case study dealing with the relationship between tourism and sustainable development. In particular a special focus on local specificities seems to be present in policy planning and project implementation. Even if seaside tourism is prevailing, initiatives towards sustainability are concentrated on environmental, rural and cultural tourism. The Country is characterized by wide variety and rich cultural heritage and tourism development is one of the most Croatian important economic activity. Now there are many institutional documents for a sustainable tourism development but those plans are not followed by appropriate implementation instruments. Actually a coordinated and integrated sustainable tourism planning at national scale is absent. At local level, counties and Tourist offices show instead great attention to sustainability, creating projects for the development of rural and insular tourism. A particular example is the County of Istria: it is not characterized by seasonal tourism and it is able to promote an integrated tourism development. Regions and types of tourism - This paper (*) is meant to analyze the development and evolution of the tourist sector in Croatia, also with reference to the latest policy planning concerning environmental sustainability. Croatia can be considered an interesting case study on the relationship between tourism and sustainable development. -

Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas

The World Bank Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas October 2009 www.erm.com Delivering sustainable solutions in a more competitive world The World Bank /PROFOR Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas October 2009 Prepared by: James Spurgeon (ERM Ltd), Nick Marchesi (Pescares), Zrinca Mesic (Oikon) and Lee Thomas (Independent). For and on behalf of Environmental Resources Management Approved by: Eamonn Barrett Signed: Position: Partner Date: 27 October 2009 This report has been prepared by Environmental Resources Management the trading name of Environmental Resources Management Limited, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. Environmental Resources Management Limited Incorporated in the United Kingdom with registration number 1014622 Registered Office: 8 Cavendish Square, London, W1G 0ER CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 AIMS 2 1.3 APPROACH 2 1.4 STRUCTURE OF REPORT 3 1.5 WHAT DO WE MEAN BY SUSTAINABLE FINANCE 3 2 PA FINANCING IN CROATIA 5 2.1 CATEGORIES OF PROTECTED -

Lepidoptera: Crambidae) New to the Fauna of Croatia

Acta entomologica serbica, 20 20 , 25(1): xx -xx UDC DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3735368 THREE MONTANE GRASS MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA: CRAMBIDAE) NEW TO THE FAUNA OF CROATIA TONI KOREN Association Hyla, Lipovac I 7, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Three species of grass moths (Crambidae) were recorded for the first time in Croatia. Udea alpinalis and Crambus ericella were found on the peaks of Mts. Guslica and Snježnik in Gorski Kotar region, while Catoptria pyramidellus was recorded on various mountain chains across the country. The discovery of three montane species in Croatia demonstrates the lack of Microlepidoptera surveys in these areas and the need for further research. KEY WORDS : Udea alpinalis, Crambus ericella, Catoptria pyramidellus, diversity , Gorski Kotar, mountains Introduction Grass moths (Crambidae) belong to one of the best studied Microlepidoptera groups in Europe, with a surprising number of available publications (Leraut, 2012; Slamka, 2006, 2008, 2013). However, the Crambidae fauna of many countries, especially in eastern Europe, has remained poorly studied. This is easily noticeable from the distribution maps published in a book series “Pyraloidea of Europe” (Slamka, 2006, 2008, 2013, 2019). Here, the highest occurrence of species is shown for Croatia, with a very limited number of records in eastern Europe. Only recently, a tentative checklist of all Pyraloidea of Croatia was published (Gumhalter, 2019). Although the checklist is based almost entirely on published papers and the examination of several smaller collections, it is useful as a good starting point to explore the Crambidae and Pyralidae fauna of the country. 2 T. -

Croatia-10-Preview.Pdf

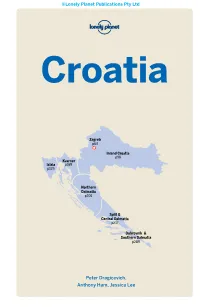

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Croatia Zagreb p64 #_ Inland Croatia p98 Kvarner Istria p169 p125 Northern Dalmatia p206 Split & Central Dalmatia p237 Dubrovnik & Southern Dalmatia p289 Peter Dragicevich, Anthony Ham, Jessica Lee PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Croatia . 4 ZAGREB . 64 Buzet . 153 Croatia Map . .. 6 Sights . 65 Roč . 156 Hum . 156 Croatia’s Top 17 . 8 Tours . 79 Pazin . 157 Need to Know . 16 Festivals & Events . 81 Sleeping . 83 Svetvinčenat . 159 What’s New . 18 Eating . 85 Labin & Rabac . 160 If You Like . 19 Drinking & Nightlife . 87 Month by Month . 22 Entertainment . 92 KVARNER . 169 Itineraries . 26 Shopping . 93 Rijeka . 171 Outdoor Activities . 36 Around Rijeka . 176 Croatia’s Islands . 44 INLAND CROATIA . 98 Risnjak National Park . 176 Volosko . 177 Travel with Children . 52 Around Zagreb . 99 Samobor . 99 Opatija . 178 Eat & Drink Like a Local . 55 Mt Medvednica . 102 Učka Nature Park . .. 180 Lošinj & Cres Islands . .. 181 Regions at a Glance . 60 Zagorje . 103 Klanjec . 104 Beli . 182 Krapinske Toplice . 104 Cres Town . 183 IASCIC/SHUTTERSTOCK © IASCIC/SHUTTERSTOCK Krapina . 105 Valun . 185 Varaždin . 107 Lubenice . 186 Međimurje . 111 Osor . 186 Slavonia . 112 Nerezine . 187 Ðakovo . 113 Mali Lošinj . 187 Osijek . 114 Veli Lošinj . 190 Baranja . 119 Krk Island . 192 Vukovar . 121 Malinska . 192 Ilok . 123 Krk Town . 193 Punat . 195 KOPAČKI RIT NATURE PARK P119 ISTRIA . 125 Vrbnik . 195 Baška . 196 Istria’s West Coast . 127 East Kvarner Coast . 198 Pula . 127 JUSTIN FOULKES/LONELY PLANET © PLANET FOULKES/LONELY JUSTIN Crikvenica . 198 Brijuni Islands . 134 Senj . 199 Vodnjan . 135 Rab Island . 200 Bale . 136 Rab Town . -

Walks and Treks in Croatia

WALKS AND TREKS IN CROATIA About the Author Rudolf Abraham (www.rudolfabraham.co.uk) is an award-winning travel writer and photographer specialising in Croatia, Central and Eastern Europe. He is the author of more than 10 books, and his work is published widely in magazines. He first visited Croatia in the late 1990s, returned to live in Zagreb for two years, and continues to make several trips a year to his favourite country in Europe. WALKS AND TREKS IN CROATIA Other Cicerone guides by the author St Oswald’s Way and St Cuthbert’s Way The Islands of Croatia MOUNTAIN TRAILS AND NATIONAL PARKS, The Mountains of Montenegro INCLUDING VELEBIT, DINARA AND PLITVICE The Peaks of the Balkans Trail Torres del Paine by Rudolf Abraham Acknowledgements For this third edition of Walks and Treks in Croatia, thanks are due to Tanja Augustinović at the Kvarner Tourist Office, Marinko Jakovljević at the Fužine Tourist Office, Silvija Sobol at the Risnjak National Park Office, Dragica Jović of the Paklenica National Park Office, Dajana Tepšić at the Istrian Tourist Office, Dubravko Primorac at Lobagola in Zagreb, Griet and Anri at Kuća Baijlo in Zadar, Ulrich Teitz at Deutsche Bahn, Jakov Žarko for his company on Dinara, and members of the HGSS and Dinaridi. Finally, for her advice, and company on a number of these routes, and for her help with the language section I must thank my wife Ivana – with whom I first JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, discovered Velebit, and to whom this book is dedicated. OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Rudolf Abraham 2019 CONTENTS Third edition 2019 ISBN: 978 1 85284 769 2 Map key ..................................................... -

Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation National Park Risnjak

ACTION PLAN FOR CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION NATIONAL PARK RISNJAK IRMO Institut za razvoj i međunarodne odnose Institute for Development and International Relations Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation National Park Risnjak Zagreb, September 1, 2017 Project: Climate Change in National Parks and Nature Parks of the Republic of Croatia: Management and Development Options Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund (FZOIEU) Institute for Development and International Relations (IRMO) Publisher: Institute for Development and International Relations, Zagreb Authors: Miljenko Gašparac, NP Risnjak Dragan Turk, NP Risnjak Sanja Tišma, IRMO Ana-Maria Boromisa, IRMO Marina Funduk, IRMO Translation: Jan Ruk Desing and layout: Dragana Markanović National Park Risnjak is a pilot area on the project “Climate Change in National Parks and Nature Parks of the Republic of Croatia: Management and Development Options” developed in cooperation with the Institute for Development and International Relations from Zagreb with the financial support of the Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund. 3 Contents 1. SITUATION ANALYSIS 6 1.1. Introduction 6 1.2. The establishment of the process 7 1.3. Assessment of human and financial resources and funding opportunities 17 1.3.1. Human resources 17 1.3.2. Financial resources and funding opportunities 17 1.4. Collecting data on the National Park 18 1.4.1. Biodiversity 19 1.4.2. Ecological Network of the Republic of Croatia 20 1.4.3. Forests 20 1.4.4. Other habitats 21 1.4.5. Protection zones in NPR 23 1.5. Communication and dissemination of data 25 1.6. Tourist valorization of the area 26 Contents 2. -

A New Finding of the Species Botrychium Matricariifolium (Retz.) A

NAT. CROAT. VOL. 20 No 1 229¿232 ZAGREB June 30, 2011 short communication/kratko priop}enje A NEW FINDING OF THE SPECIES BOTRYCHIUM MATRICARIIFOLIUM (RETZ.) A. BR. EX KOCH (OPHIOGLOSSACEAE) IN CROATIA LJILJANA BOROVE^KI –VOSKA1,ROKO ^I^MIR2 &DUBRAVKO [INCEK3 1Elementary School \urmanec, \urmanec bb, 49 225 \urmanec, Croatia 2Uljani~ki put 19, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia 3R. Bo{kovi}a 14c, 42 000 Vara`din, Croatia Borove~ki-Voska, Lj., ^i~mir, R. & [incek, D.: A new finding of the species Botrychium matricariifolium (Retz.) A. Br. ex Koch (Ophioglossaceae) in Croatia. Nat. Croat., Vol. 20, No. 1., 229–232, 2011, Zagreb. In this short communication a new locality of the species Botrychium matricariifolium (Retz.) A. Br. ex Koch in the Risnjak National Park area (Croatia) is reported. Thirty years ago, after this spe- cies became extinct on Medvednica mountain, which was the only known locality in Croatia, it got the status of Regionally Extinct taxon (IUCN category RE). The new finding brings this species back to the list of recent national flora. Key words: Botrychium matricariifolium, new locality, Risnjak NP, Croatia Borove~ki-Voska, Lj., ^i~mir, R. & [incek, D.: Novi nalaz vrste Botrychium matricariifolium (Retz.) A. Br. ex Koch (Ophioglossaceae) u Hrvatskoj. Nat. Croat., Vol. 20, No. 1., 229–232, 2011, Zagreb. U ovom kratkom priop}enju objavljuje se novo nalazi{te vrste Botrychium matricariifolium (Retz.) A. Br. ex Koch na podru~ju NP Risnjak (Hrvatska). Nakon {to je ta vrsta prije 30-ak godina izumrla na Medvednici, jedinom poznatom nalazi{tu u R. Hrvatskoj, dobila je status regionalno izumrle svojte (IUCN kategorija RE). -

E525 January 2002

E525 January 2002 Croatia Karst Ecosystem Conservation Project ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized Back2round: Croatia enjoys unusually rich biodiversity of global significance due to its geography, between the Mediterranean and Central-European continental climatic regions, and its geology, which is predominantly karst. The term "karst" originated in Croatia and is applied to a specific landscape and morphology characterized by the presence of limestone or other soluble rocks, where drainage has been largely diverted into subterranean routes. The globally prominent Croatian karst ecosystems host 3,500 species of flora (283 endemic), 12 species of amphibians, 36 species of reptiles, 200 species of resident birds, 79 species of mammals, and 64 species of freshwater fish, (11 endemic). Subterranean karst habitats support an ever increasing list of newly discovered endemic trogloditic (eyeless and adapted for an entirely subterranean existence) species and families. These include one new species, genus and family of leech Croatobranchus mestrovi. Croatia's subterranean biodiversity also includes the world's only known cave Public Disclosure Authorized sponge, the only known cave calm, and the only known cave polychaete worm. Croatia is famous for its karst freshwater ecosystems which include travertine/tuffa-building communities of micro-organisms. The resulting travertine barriers, some estimated to be over 40,000 years old, have led to the spectacular lakes and waterfalls now protected within two national parks - Plitvice and Krka. The global significance of Croatia's karst ecosystem is internationally recognized. Plitvice Lakes National Park is on the UNESCO's World List of Natural and Cultural Heritage. The Velebit Mountain Range is part of the UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere Program, and has been identified by the World Wildlife Fund's Forest Hotspot Initiative as one of the ten most important forest areas in the Mediterranean region. -

{TEXTBOOK} Walking in Croatia Pdf Free Download

WALKING IN CROATIA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rudolf Abraham | 272 pages | 01 Oct 2010 | Cicerone Press | 9781852846145 | English | Cumbria, United Kingdom Walking in Croatia PDF Book Croatia walking holiday, castles to coast Walk in style from Motovun to Opatija. Hidden Gems. See 9 Experiences. Boat Rentals 3. Almost a quarter consists of sea surface with scattered islands in the Adriatic Sea. Walking in Croatia, an introduction. Krka Wasserfall — Aussichtspunkt Loop from Poduriljko. Also See. Day 6 — Free day. See the Kornati National Park website for more information. Tailor made: Daily departures from April to October. Take a look through our walking itineraries below to start planning your next adventure in this magnificent corner of Europe! The result is a landscape of steep jagged escarpments , through which steep-sided gorges and canyons are cleft by the rivers draining the higher slopes. Walking Tour of Split Split. Segway Tours 1. Popular around Croatia. Booker travel agency Split. Honeymoon spot. Small group travel. Walking Tours in Croatia Immerse yourself in the authentic charm of Croatia on a self-guided walking tour. The islands are generally quite dry; the further away from the mainland the drier they get. A mountain hut in Risnjak National Park, a fantastic area for walking in Croatia. Walking in Croatia Writer The impressive waterfalls in Krka National Park. Travel Team If you would like some help or advice, or just want to discuss your ideas for your next trip, do give us a call. Day 6 — Free day. See 10 Experiences. Walk Day 5: approx 3 hours Today we propos e a liner coastal walk, walking along the coastal path from Baska Voda to the market town of Mararska, The trail leaves near our hotel heading South East on a developed coastal path, part of which is sheltered by a canopy of trees, again we pass older style holiday accommodation before moving on enjoying magnificent sea views before arriving at the marina of the small coastal village of Promajna for a break. -

Protected-Natural-Heritage.Pdf

PROTECTED NATURAL HERITAGE OF THE COUNTY OF PRIMORJE-GORSKI KOTAR PROTECTED NATURAL HERITAGE OF THE COUNTY OF PRIMORJE-GORSKI KOTAR Publisher The County of Primorje-Gorski kotar On behalf of the publisher President of the County, Zlatko Komadina, Dipl. Ing. Executive publisher Glosa d.o.o., Rijeka On behalf of the executive publisher Ksenija Čulina Editor Prof. Dr. Sc. Mladen Črnjar, Head of the County Institute for Sustainable Development and Spatial Planning Executive editor Marko Randić Editorial department Prof. Dr. Sc. Mladen Črnjar, Mr. Sc. Koraljka Vahtar-Jurković, Neven Ivanić, Marko Randić Texts and captions written by Marko Randić Translation Adverbum d.o.o., Opatija Photographs Marko Randić, Želimir Gržančić (pages 28, 30, 48, 49, 52, 54, 55, 62, 66, 77, 78, 82, 88a, 94, 107, 108, 110 and 144), Mr. Sc. Ivanka Jelenić (page 96), Tješimir Marić (page 129) Graphic design Jasminka Maržić-Kazazi Print Grafički zavod Hrvatske, Zagreb PROTECTED NATURAL HERITAGE OF THE COUNTY OF PRIMORJE-GORSKI KOTAR 2006 PROTECTED NATURAL HERITAGE OF THE COUNTY OF PRIMORJE-GORSKI KOTAR Cover photograph Risnjak National Park - sub-alpine grasslands on Mount Snježnik and globe flower in bloom (Trollius europaeus). CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji SVEUČILIŠNA KNJIŽNICA RIJEKA UDK 502.7(497.5-35 Rijeka)(036) PROTECTED natural heritage of the county of Primorje-Gorski kotar / <texts and captions written by Marko Randić ; photographs Marko Randić ... et al.>. - Rijeka : Primorsko-goranska županija, 2006. Prijevod djela : Zaštićena prirodna baština Primorsko-goranske županije. ISBN 953-7221-16-4 I. Prirodna baština -- Primorsko-goranska županija -- Vodič II. Primorsko- goranska županija -- Prirodna baština – Vodič 110707055 FOREWORD The County of Primorje-Gorski kotar is abundant in valuable nature areas with preserved unspoiled landscape and beauties of nature. -

Brown Bear Habitat Quality in Gorski Kotar, Croatia

BROWNBEAR HABITATQUALITY IN GORSKIKOTAR, CROATIA JOSIP KUSAK,Biology Department, Veterinary Faculty of the Universityof Zagreb,Heinzelova 55, 10000 Zagreb,Croatia, email: [email protected] [email protected] DJUROHUBER, Biology Department, Veterinary Faculty of the Universityof Zagreb,Heinzelova 55, 10000Zagreb, Croatia, email: [email protected] Abstract: The brown bear (Ursus arctos) population in Croatia is a possible source of bears for reintroducingand augmenting disappearing Europeanbrown bear populations in western Europe. For successful reintroduction,knowledge about bear habitat quality of both source and target areas is necessary. We developed a habitat suitability index (HSI) model to assess Europeanbrown bear habitatquality in Gorski kotar, Croatia. Importanthabitat variables included seasonal foods, cover, roads, and fragmentation. Food sources were available year-round,whereas foraging and denning cover were more limited. Humaninfluence was manifestedthrough a relatively high density of roads (1.91 km/km2),which included forest roads. Habitatfragmentation did not occur within the study area, but a highway under constructionwas a possible threat. The overall HSI value of 0.42 for the entire area indicatedthat brown bear habitatin Gorski kotar is average. Brown bear habitatcould be improved with changes in managementpractices such as closing forest roads, seasonally avoiding logging in denning areas, and reducing reforestationof beech-fir (Fagus sp.-Abies sp.) areas to spruce (Picea abies). Ursus 10:281-291 Key words: Croatia,European brown bear, habitat quality, habitat suitability index, Ursus arctos. One of the largest remainingbrown bear populations This study was fundedby the CroatianMinistry of Sci- in Europe occurs in the Dinara, Sara, and Pindus moun- ence, Wildbiologische Geselschaft-Miinchen, John tains (approximately 60,000 km2) spanning Slovenia, Sheldon Bevins Memorial Foundation, and Stiftung Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Monte Negro, EuropaiischeNaturerbe (EURONATUR). -

Résultats De La Première Évaluation De La Gestion Des Aires Protégées

Effectiveness of Protected Area Management in Croatia Results of the First Evaluation of Protected Area Management in Croatia Using the RAPPAM Methodology Effectiveness of Protected Area Management in Croatia Final report of the RAPPAM analysis Authors: Deni Porej and Željka Rajković Recommended citation format: Porej, D. & Rajković, Ž., 2009, Effectiveness of Protected Area Management in Croatia: Results of the First Evaluation of Protected Area Management in Croatia Using the RAPPAM Methodology, Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia. A project implemented in collaboration between the Republic of Croatia Ministry of Culture and the WWF Mediterranean Programme. When summarizing information from this report, please use the above form of citation. However, for the use of detailed results of the analysis, a written agreement should be obtained from both authors. Context Executive summary 5 1. Introduction and context 7 1.1. Biological diversity in Croatia 7 1.2. Nature protection system in Croatia 8 2. Application of the methodology 13 2.1. Programme of Work on Protected Areas of the Convention on Biological Diversity 13 2.2. Rapid Assessment and Prioritization of Protected Area Management (RAPPAM) Methodology) 14 2.3. Application of the RAPPAM Methodology in Croatia 16 3. Results and analysis 17 3.1. Pressures and threats in protected areas 17 3.1.1. System‐wide threats 18 3.1.1.1. Threats and pressures in different types of protected areas 18 3.1.2. Threat ranking 21 3.1.2.1. Forest management 21 3.1.2.2. Hunting and fishing 22 3.1.2.3. Unsettled disputes regarding land tenure and use rights 22 3.1.2.4.