Donald Trump and the 2018 Midterm Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electoral Order and Political Participation: Election Scheduling, Calendar Position, and Antebellum Congressional Turnout

Electoral Order and Political Participation: Election Scheduling, Calendar Position, and Antebellum Congressional Turnout Sara M. Butler Department of Political Science UCLA Los Angeles, CA 90095-1472 [email protected] and Scott C. James Associate Professor Department of Political Science UCLA Los Angeles, CA 90095-1472 (310) 825-4442 [email protected] An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 3-6, 2008, Chicago, IL. Thanks to Matt Atkinson, Kathy Bawn, and Shamira Gelbman for helpful comments. ABSTRACT Surge-and-decline theory accounts for an enduring regularity in American politics: the predictable increase in voter turnout that accompanies on-year congressional elections and its equally predictable decrease at midterm. Despite the theory’s wide historical applicability, antebellum American political history offers a strong challenge to its generalizability, with patterns of surge-and-decline nowhere evident in the period’s aggregate electoral data. Why? The answer to this puzzle lies with the institutional design of antebellum elections. Today, presidential and on-year congressional elections are everywhere same-day events. By comparison, antebellum states scheduled their on- year congressional elections in one of three ways: before, after, or on the same day as the presidential election. The structure of antebellum elections offers a unique opportunity— akin to a natural experiment—to illuminate surge-and-decline dynamics in ways not possible by the study of contemporary congressional elections alone. Utilizing quantitative and qualitative materials, our analysis clarifies and partly resolves this lack of fit between theory and historical record. It also adds to our understanding of the effects of political institutions and electoral design on citizen engagement. -

The United States and Democracy Promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the Aftermath of the Events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War

The United States and democracy promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD. in Political Science. By Abess Taqi Ph.D. candidate, University of London Internal Supervisors Dr. James Chiriyankandath (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) Professor Philip Murphy (Director, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) External Co-Supervisor Dr. Maria Holt (Reader in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster) © Copyright Abess Taqi April 2015. All rights reserved. 1 | P a g e DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: ………………………………………. Date: ……………………………………………. 2 | P a g e Abstract This thesis features two case studies exploring the George W. Bush Administration’s (2001 – 2009) efforts to promote democracy in the Arab world, following military occupation in Iraq, and through ‘democracy support’ or ‘democracy assistance’ in Lebanon. While reviewing well rehearsed arguments that emphasise the inappropriateness of the methods employed to promote Western liberal democracy in Middle East countries and the difficulties in the way of democracy being fostered by foreign powers, it focuses on two factors that also contributed to derailing the U.S.’s plans to introduce ‘Western style’ liberal democracy to Iraq and Lebanon. -

Ballot Initiatives and Electoral Timing

Ballot Initiatives and Electoral Timing A. Lee Hannah∗ Pennsylvania State University Department of Political Sciencey Abstract This paper examines the effects of electoral timing on the results of ballot initiative campaigns. Using data from 1965 to 2009, I investigate whether initiative campaign re- sults systematically differ depending on whether the legislation appears during special, midterm, or presidential elections. I also consider the electoral context, particularly the effects of surging presidential candidates on ballot initiative results. The results suggest that initiatives on morality policy are sensitive to the electoral environment, particularly to “favorable surges” provided by popular presidential candidates. Preliminary evidence suggests that tax policy is unaffected by electoral timing. Introduction The increasing use of the ballot initiative has led to heightened interest in both the popular media and among scholars. Some of the most contentious issues in American politics, once reserved for debate among elected representatives, are now being decided directly by the me- dian voter. Yet the location of the median voter fluctuates from election to election based on a number of factors that influence turnout and shape the demographic makeup of voters in a given year. This suggests that votes on ballot initiatives may be influenced by the same factors that are known to influence electoral composition. In this paper, I contrast initiatives appearing on midterm and special election ballots with those held during presidential elections, deriving hypotheses from Campbell’s (1960) theory of electoral surge and decline. I examine whether electoral timing does systematically affect results. ∗Prepared for the 2012 State Politics and Policy Conference, Rice University and University of Houston, February 16-18, 2012. -

American Review of Politics Volume 37, Issue 1 31 January 2020

American Review of Politics Volume 37, Issue 1 31 January 2020 An open a ccess journal published by the University of Oklahoma Department of Political Science in colla bora tion with the University of Okla homa L ibraries Justin J. Wert Editor The University of Oklahoma Department of Political Science & Institute for the American Constitutional Heritage Daniel P. Brown Managing Editor The University of Oklahoma Department of Political Science Richard L. Engstrom Book Reviews Editor Duke University Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in the Social Sciences American Review of Politics Volume 37 Issue 1 Partisan Ambivalence and Electoral Decision Making Stephen C. Craig Paulina S. Cossette Michael D. Martinez University of Florida Washington College University of Florida [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract American politics today is driven largely by deep divisions between Democrats and Republicans. That said, there are many people who view the opposition in an overwhelmingly negative light – but who simultaneously possess a mix of positive and negative feelings toward their own party. This paper is a response to prior research (most notably, Lavine, Johnson, and Steenbergen 2012) indicating that such ambivalence increases the probability that voters will engage in "deliberative" (or "effortful") rather than "heuristic" thinking when responding to the choices presented to them in political campaigns. Looking first at the 2014 gubernatorial election in Florida, we find no evidence that partisan ambivalence reduces the importance of party identification or increases the impact of other, more "rational" considerations (issue preferences, perceived candidate traits, economic evaluations) on voter choice. -

Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy In Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy, Erik J. Engstrom offers an important, historically grounded perspective on the stakes of congressional redistricting by evaluating the impact of gerrymandering on elections and on party control of the U.S. national government from 1789 through the reapportionment revolution of the 1960s. In this era before the courts supervised redistricting, state parties enjoyed wide discretion with regard to the timing and structure of their districting choices. Although Congress occasionally added language to federal- apportionment acts requiring equally populous districts, there is little evidence this legislation was enforced. Essentially, states could redistrict largely whenever and however they wanted, and so, not surpris- ingly, political considerations dominated the process. Engstrom employs the abundant cross- sectional and temporal varia- tion in redistricting plans and their electoral results from all the states— throughout U.S. history— in order to investigate the causes and con- sequences of partisan redistricting. His analysis -

Presidential Approval Ratings on Midterm Elections OLAYINKA

Presidential Approval Ratings on Midterm Elections OLAYINKA AJIBOLA BALL STATE UNIVERSITY Abstract This paper examines midterm elections in the quest to find the evidence which accounts for the electoral loss of the party controlling the presidency. The first set of theory, the regression to the mean theory, explained that as the stronger the presidential victory or seats gained in previous presidential year, the higher the midterm seat loss. The economy/popularity theories, elucidate midterm loss due to economic condition at the time of midterm. My paper assesses to know what extent approval rating affects the number of seats gain/loss during the election. This research evaluates both theories’ and the aptness to expound midterm seat loss at midterm elections. The findings indicate that both theories deserve some credit, that the economy has some impact as suggested by previous research, and the regression to the mean theories offer somewhat more accurate predictions of seat losses. A combined/integrated model is employed to test the constant, and control variables to explain the aggregate seat loss of midterm elections since 1946. Key Word: Approval Ratings, Congressional elections, Midterm Presidential elections, House of Representatives INTRODUCTION Political parties have always been an integral component of government. In recent years, looking at the Clinton, Bush, Obama and Trump administration, there are no designated explanations that attempt to explain why the President’s party lose seats. To an average person, it could be logical to conclude that the President’s party garner the most votes during midterm elections, but this is not the case. Some factors could affect the outcome of the election which could favor or not favor the political parties The trend in the midterm election over the years have yielded various results, but most often, affecting the president’s party by losing congressional house seats at midterm. -

Trump's Conundrum for in Republicans

V21, 28 Thursday, March 24, 2016 Trump’s conundrum for IN Republicans Leaders say they will support the ‘nominee,’ while McIntosh raises down-ballot alarms By BRIAN A. HOWEY BLOOMINGTON – GOP presidential front runner Donald J. Trump is just days away from his Indiana political debut, and Hoosier Republicans are facing a multi-faceted conundrum. Do they join the cabal seeking to keep the nominating number of delegates away from him prior to the Republi- can National Convention in July? This coming as Trump impugns the wife of Sen. Ted Cruz, threatening to “spill the beans” on her after two weeks of cam- paign violence and nativist fear mongering representing a sharp departure dent Mitch Daniels, former secretary of state Condoleezza modern Indiana internationalism. Rice, former senator Tom Coburn or former Texas governor Do they participate in a united front seeking an Rick Perry? alternative such as Sen. Ted Cruz, Ohio Gov. John Kasich, Or do they take the tack expressed by Gov. Mike or a dark horse consensus candidate such as Purdue Presi- Continued on page 3 Election year data By MORTON MARCUS INDIANAPOLIS – Let’s clarify some issues that may arise in this contentious political year. These data covering 2005 to 2015 may differ somewhat from those offered by other writers, speakers, and researchers. Why? These data are “This plan addresses our state’s from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ “Quarterly Census of immediate road funding needs Wages and Employment” via the while ensuring legislators come Indiana Department of Workforce Development’s Hoosiers by the back to the table next year ready Numbers website, where only the first three quarters of 2015 are to move forward on a long-term available. -

Understanding Evangelical Support For, and Opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 9-1-2020 Understanding Evangelical Support for, and Opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election Joseph Thomas Zichterman Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Political Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Zichterman, Joseph Thomas, "Understanding Evangelical Support for, and Opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election" (2020). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5570. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7444 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Understanding Evangelical Support for, and Opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election by Joseph Thomas Zichterman A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Thesis Committee: Richard Clucas, Chair Jack Miller Kim Williams Portland State University 2020 Abstract This thesis addressed the conundrum that 81 percent of evangelicals supported Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election, despite the fact that his character and comportment commonly did not exemplify the values and ideals that they professed. This was particularly perplexing to many outside (and within) evangelical circles, because as leaders of America’s “Moral Majority” for almost four decades, prior to Trump’s campaign, evangelicals had insisted that only candidates who set a high standard for personal integrity and civic decency, were qualified to serve as president. -

Copyright © 2019 Shaun Daniel Lewis

Copyright © 2019 Shaun Daniel Lewis All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. TEACHING A THEOLOGY OF CIVIL GOVERNMENT AT SOUTHERN VIEW CHAPEL IN SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS __________________ A Project Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry __________________ by Shaun Daniel Lewis May 2019 APPROVAL SHEET TEACHING A THEOLOGY OF CIVIL GOVERNMENT AT SOUTHERN VIEW CHAPEL IN SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS Shaun Daniel Lewis Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Michael S. Wilder (Faculty Supervisor) __________________________________________ Shane W. Parker Date______________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS . vi PREFACE . vii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Context . 1 Rationale . 5 Purpose . 6 Goals . 6 Research Methodology . 7 Definition and Limitations/Delimitations . 9 Conclusion . 10 2. THE BIBLICAL AND THEOLOGICAL BASIS FOR CIVIL GOVERNMENT AND A BELIEVER’S RESPONSE . 11 The Beginning of Civil Government (Gen 1-9) . 11 Submission: A Christian Response to Civil Government . 18 The Limits of Submission: A Case Study (Acts 5:29) . 29 Prayer: A Christian Response (1 Tim 2:1-4) . 32 Conclusion . 36 3. HISTORICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL ISSUES PERTAINING TO A BIBLICAL RESPONSE TO CIVIL GOVERNMENT . 37 A History of Evangelicals in the Political Arena . 38 iii Chapter Page A Biblical Philosophy for Engaging Civil Government . 50 Conclusion . 61 4. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION . 64 Scheduling the Project . 64 Developing the Curriculum . 65 Teaching the Class . -

CIVIC CHARITY and the CONSTITUTION in 2018, Professor Amy Chua Published a Book Titled, Political Tribes: Group Instinct And

CIVIC CHARITY AND THE CONSTITUTION THOMAS B. GRIFFITH* In 2018, Professor Amy Chua published a book titled, Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations.1 By Professor Chua’s account, the idea for the book started as a critique of the failure of American foreign policy to recognize that tribal loyalties were the most important political commitments in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq.2 But as Professor Chua studied the role such loyalties played in these countries, she recognized that the United States is itself divided among political tribes.3 Of course, Professor Chua is not the first or the only scholar or pundit to point this out.4 I am neither a scholar nor a pundit, but I am an observer of the American political scene. I’ve lived during the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis. I remember well the massive street demonstrations protesting American involvement in the war in Vietnam, race riots in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., the assassinations of President John F. * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. This Essay is based on remarks given at Harvard Law School in January 2019. 1. AMY CHUA, POLITICAL TRIBES: GROUP INSTINCT AND THE FATE OF NATIONS (2018). 2. See id. at 2–3. 3. Id. at 166, 177. 4. See, e.g., BEN SASSE, THEM: WHY WE HATE EACH OTHER—AND HOW TO HEAL (2018); Arthur C. Brooks, Opinion, Our Culture of Contempt, N.Y. TIMES (Mar. 2, 2019), https://nyti.ms/2Vw3onl [https://perma.cc/TS85-VQFD]; David Brooks, Opinion, The Retreat to Tribalism, N.Y. -

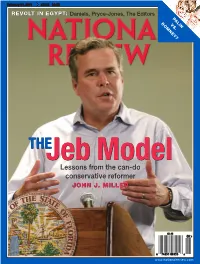

Lessons from the Can-Do Conservative Reformer JOHN J

2011_02_21 postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 2/1/2011 7:22 PM Page 1 February 21, 2011 49145 $3.95 REVOLT IN EGYPT: Daniels, Pryce-Jones, The Editors PALIN ROMNEY?VS. THEJebJeb Model Model Lessons from the can-do conservative reformer JOHN J. MILLER $3.95 08 0 74851 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 2/1/2011 12:50 PM Page 1 ÊÊ ÊÊ 1 of Every 5 Homes and Businesses is Powered ÊÊ ÊÊ Ê by Reliable, Aordable Nuclear Energy. /VDMFBSFOFSHZTVQQMJFTPG"NFSJDBTFMFDUSJDJUZXJUIPVU U.S. Electricity Generation FNJUUJOHBOZHSFFOIPVTFHBTFT-BTUZFBS SFBDUPSTJO Fuel Shares Natural Gas TUBUFTQSPEVDFENPSFUIBOCJMMJPOLJMPXBUUIPVSTPG 23.3% FMFDUSJDJUZ KVTUTIZPGBSFDPSEZFBSGPSFMFDUSJDJUZHFOFSBUJPO GSPNOVDMFBSQPXFSQMBOUT/FXOVDMFBSFOFSHZGBDJMJUJFTBSF CFJOHCVJMUUPEBZUIBUXJMMCFBNPOHUIFNPTUDPTUFGGFDUJWF Nuclear 20.2% GPSDPOTVNFSTXIFOUIFZDPNFPOMJOF Coal Hydroelectric 44.6% Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê ÊÊ ÊÊ Ê 5PNFFUPVSJODSFBTJOHEFNBOEGPSFMFDUSJDJUZ XFOFFEB 6.8% Renewables DPNNPOTFOTF CBMBODFEBQQSPBDIUPFOFSHZQPMJDZUIBUJODMVEFT Oil 1 and Other % 4.1% MPXDBSCPOTPVSDFTTVDIBTOVDMFBS XJOEBOETPMBSQPXFS Source: 2009, U.S. Energy Information Administration 7JTJUOFJPSHUPMFBSONPSF toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 2/2/2011 1:23 PM Page 1 Ramesh Ponnuru on Palin vs. Romney Contents p. 24 FEBRUARY 21, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 3 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 32 The Education Ex-Governor Jeb Bush is quietly building a legacy as something other than the Bush who didn’t reach the Oval Office. Governors BOOKS, ARTS everywhere boast of a desire to & MANNERS become ‘the education governor.’ 47 THE GILDED GUILD As Florida’s chief executive, Bush Robert VerBruggen reviews Schools really was one. John J. Miller for Misrule: Legal Academia and an Overlawyered America, by Walter Olson. COVER: CHARLES W. LUZIER/REUTERS/CORBIS 48 AUSTRALIAN MODEL ARTICLES Arthur W. -

Registering the Youth Through Voter Preregistration.Pdf

\\server05\productn\N\NYL\13-3\NYL304.txt unknown Seq: 1 6-DEC-10 11:20 REGISTERING THE YOUTH THROUGH VOTER PREREGISTRATION* Michael P. McDonald† Matthew Thornburg†† INTRODUCTION .............................................. 551 R I. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF PREREGISTRATION IN FLORIDA AND HAWAII ............................... 555 R II. IMPLEMENTATION OF PREREGISTRATION IN FLORIDA AND HAWAII ........................................ 557 R III. MEASURING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PREREGISTRATION IN FLORIDA AND HAWAII ............................. 562 R IV. RECOMMENDATIONS ................................. 568 R CONCLUSION................................................ 570 R INTRODUCTION Young Americans are less likely to vote than older Americans.1 During the 2008 presidential election, the turnout rate for citizens age eighteen to twenty-four was twenty percentage points lower than citi- zens age sixty-five and older.2 There is considerable interest among policy makers and advocates to devise solutions to low civic engage- * This research is generously supported in part by a grant from the Pew Charita- ble Trusts, Make Voting Work Project. The authors are indebted to Tyler Culberson for providing research assistance. † Michael P. McDonald is an Associate Professor of Government and Politics at George Mason University and a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution. †† Matthew Thornburg is a Ph.D. candidate of Political Science at George Mason University. 1. See, e.g., RAYMOND E. WOLFINGER & STEPHEN ROSENSTONE, WHO VOTES? 37–60 (1980); Jan E. Leighley & Jonathan Nagler, Socioeconomic Class Bias in Turn- out, 1964–1988: The Voters Remain the Same, 86 AM. POL. SCI. REV. 725, 733–34 (1992). 2. See THOM FILE & SARAH CRISSEY, U.S. CENSUS BUREAU, P20-562, VOTING AND REGISTRATION IN THE ELECTION OF NOVEMBER 2008 4 (2010), http:// www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p20-562.pdf.