Book Reviews / 145

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States and Democracy Promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the Aftermath of the Events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War

The United States and democracy promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD. in Political Science. By Abess Taqi Ph.D. candidate, University of London Internal Supervisors Dr. James Chiriyankandath (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) Professor Philip Murphy (Director, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) External Co-Supervisor Dr. Maria Holt (Reader in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster) © Copyright Abess Taqi April 2015. All rights reserved. 1 | P a g e DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: ………………………………………. Date: ……………………………………………. 2 | P a g e Abstract This thesis features two case studies exploring the George W. Bush Administration’s (2001 – 2009) efforts to promote democracy in the Arab world, following military occupation in Iraq, and through ‘democracy support’ or ‘democracy assistance’ in Lebanon. While reviewing well rehearsed arguments that emphasise the inappropriateness of the methods employed to promote Western liberal democracy in Middle East countries and the difficulties in the way of democracy being fostered by foreign powers, it focuses on two factors that also contributed to derailing the U.S.’s plans to introduce ‘Western style’ liberal democracy to Iraq and Lebanon. -

Trump's Conundrum for in Republicans

V21, 28 Thursday, March 24, 2016 Trump’s conundrum for IN Republicans Leaders say they will support the ‘nominee,’ while McIntosh raises down-ballot alarms By BRIAN A. HOWEY BLOOMINGTON – GOP presidential front runner Donald J. Trump is just days away from his Indiana political debut, and Hoosier Republicans are facing a multi-faceted conundrum. Do they join the cabal seeking to keep the nominating number of delegates away from him prior to the Republi- can National Convention in July? This coming as Trump impugns the wife of Sen. Ted Cruz, threatening to “spill the beans” on her after two weeks of cam- paign violence and nativist fear mongering representing a sharp departure dent Mitch Daniels, former secretary of state Condoleezza modern Indiana internationalism. Rice, former senator Tom Coburn or former Texas governor Do they participate in a united front seeking an Rick Perry? alternative such as Sen. Ted Cruz, Ohio Gov. John Kasich, Or do they take the tack expressed by Gov. Mike or a dark horse consensus candidate such as Purdue Presi- Continued on page 3 Election year data By MORTON MARCUS INDIANAPOLIS – Let’s clarify some issues that may arise in this contentious political year. These data covering 2005 to 2015 may differ somewhat from those offered by other writers, speakers, and researchers. Why? These data are “This plan addresses our state’s from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ “Quarterly Census of immediate road funding needs Wages and Employment” via the while ensuring legislators come Indiana Department of Workforce Development’s Hoosiers by the back to the table next year ready Numbers website, where only the first three quarters of 2015 are to move forward on a long-term available. -

Understanding Evangelical Support For, and Opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 9-1-2020 Understanding Evangelical Support for, and Opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election Joseph Thomas Zichterman Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Political Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Zichterman, Joseph Thomas, "Understanding Evangelical Support for, and Opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election" (2020). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5570. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7444 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Understanding Evangelical Support for, and Opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election by Joseph Thomas Zichterman A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Thesis Committee: Richard Clucas, Chair Jack Miller Kim Williams Portland State University 2020 Abstract This thesis addressed the conundrum that 81 percent of evangelicals supported Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election, despite the fact that his character and comportment commonly did not exemplify the values and ideals that they professed. This was particularly perplexing to many outside (and within) evangelical circles, because as leaders of America’s “Moral Majority” for almost four decades, prior to Trump’s campaign, evangelicals had insisted that only candidates who set a high standard for personal integrity and civic decency, were qualified to serve as president. -

Copyright © 2019 Shaun Daniel Lewis

Copyright © 2019 Shaun Daniel Lewis All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. TEACHING A THEOLOGY OF CIVIL GOVERNMENT AT SOUTHERN VIEW CHAPEL IN SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS __________________ A Project Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry __________________ by Shaun Daniel Lewis May 2019 APPROVAL SHEET TEACHING A THEOLOGY OF CIVIL GOVERNMENT AT SOUTHERN VIEW CHAPEL IN SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS Shaun Daniel Lewis Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Michael S. Wilder (Faculty Supervisor) __________________________________________ Shane W. Parker Date______________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS . vi PREFACE . vii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Context . 1 Rationale . 5 Purpose . 6 Goals . 6 Research Methodology . 7 Definition and Limitations/Delimitations . 9 Conclusion . 10 2. THE BIBLICAL AND THEOLOGICAL BASIS FOR CIVIL GOVERNMENT AND A BELIEVER’S RESPONSE . 11 The Beginning of Civil Government (Gen 1-9) . 11 Submission: A Christian Response to Civil Government . 18 The Limits of Submission: A Case Study (Acts 5:29) . 29 Prayer: A Christian Response (1 Tim 2:1-4) . 32 Conclusion . 36 3. HISTORICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL ISSUES PERTAINING TO A BIBLICAL RESPONSE TO CIVIL GOVERNMENT . 37 A History of Evangelicals in the Political Arena . 38 iii Chapter Page A Biblical Philosophy for Engaging Civil Government . 50 Conclusion . 61 4. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION . 64 Scheduling the Project . 64 Developing the Curriculum . 65 Teaching the Class . -

CIVIC CHARITY and the CONSTITUTION in 2018, Professor Amy Chua Published a Book Titled, Political Tribes: Group Instinct And

CIVIC CHARITY AND THE CONSTITUTION THOMAS B. GRIFFITH* In 2018, Professor Amy Chua published a book titled, Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations.1 By Professor Chua’s account, the idea for the book started as a critique of the failure of American foreign policy to recognize that tribal loyalties were the most important political commitments in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq.2 But as Professor Chua studied the role such loyalties played in these countries, she recognized that the United States is itself divided among political tribes.3 Of course, Professor Chua is not the first or the only scholar or pundit to point this out.4 I am neither a scholar nor a pundit, but I am an observer of the American political scene. I’ve lived during the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis. I remember well the massive street demonstrations protesting American involvement in the war in Vietnam, race riots in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., the assassinations of President John F. * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. This Essay is based on remarks given at Harvard Law School in January 2019. 1. AMY CHUA, POLITICAL TRIBES: GROUP INSTINCT AND THE FATE OF NATIONS (2018). 2. See id. at 2–3. 3. Id. at 166, 177. 4. See, e.g., BEN SASSE, THEM: WHY WE HATE EACH OTHER—AND HOW TO HEAL (2018); Arthur C. Brooks, Opinion, Our Culture of Contempt, N.Y. TIMES (Mar. 2, 2019), https://nyti.ms/2Vw3onl [https://perma.cc/TS85-VQFD]; David Brooks, Opinion, The Retreat to Tribalism, N.Y. -

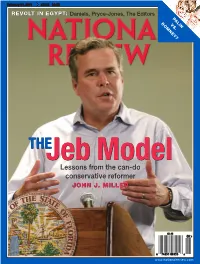

Lessons from the Can-Do Conservative Reformer JOHN J

2011_02_21 postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 2/1/2011 7:22 PM Page 1 February 21, 2011 49145 $3.95 REVOLT IN EGYPT: Daniels, Pryce-Jones, The Editors PALIN ROMNEY?VS. THEJebJeb Model Model Lessons from the can-do conservative reformer JOHN J. MILLER $3.95 08 0 74851 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 2/1/2011 12:50 PM Page 1 ÊÊ ÊÊ 1 of Every 5 Homes and Businesses is Powered ÊÊ ÊÊ Ê by Reliable, Aordable Nuclear Energy. /VDMFBSFOFSHZTVQQMJFTPG"NFSJDBTFMFDUSJDJUZXJUIPVU U.S. Electricity Generation FNJUUJOHBOZHSFFOIPVTFHBTFT-BTUZFBS SFBDUPSTJO Fuel Shares Natural Gas TUBUFTQSPEVDFENPSFUIBOCJMMJPOLJMPXBUUIPVSTPG 23.3% FMFDUSJDJUZ KVTUTIZPGBSFDPSEZFBSGPSFMFDUSJDJUZHFOFSBUJPO GSPNOVDMFBSQPXFSQMBOUT/FXOVDMFBSFOFSHZGBDJMJUJFTBSF CFJOHCVJMUUPEBZUIBUXJMMCFBNPOHUIFNPTUDPTUFGGFDUJWF Nuclear 20.2% GPSDPOTVNFSTXIFOUIFZDPNFPOMJOF Coal Hydroelectric 44.6% Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê Ê ÊÊ ÊÊ Ê 5PNFFUPVSJODSFBTJOHEFNBOEGPSFMFDUSJDJUZ XFOFFEB 6.8% Renewables DPNNPOTFOTF CBMBODFEBQQSPBDIUPFOFSHZQPMJDZUIBUJODMVEFT Oil 1 and Other % 4.1% MPXDBSCPOTPVSDFTTVDIBTOVDMFBS XJOEBOETPMBSQPXFS Source: 2009, U.S. Energy Information Administration 7JTJUOFJPSHUPMFBSONPSF toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 2/2/2011 1:23 PM Page 1 Ramesh Ponnuru on Palin vs. Romney Contents p. 24 FEBRUARY 21, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 3 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 32 The Education Ex-Governor Jeb Bush is quietly building a legacy as something other than the Bush who didn’t reach the Oval Office. Governors BOOKS, ARTS everywhere boast of a desire to & MANNERS become ‘the education governor.’ 47 THE GILDED GUILD As Florida’s chief executive, Bush Robert VerBruggen reviews Schools really was one. John J. Miller for Misrule: Legal Academia and an Overlawyered America, by Walter Olson. COVER: CHARLES W. LUZIER/REUTERS/CORBIS 48 AUSTRALIAN MODEL ARTICLES Arthur W. -

Do Christians Have a Worldview?

THREE BOOKS ON POLITICS: A REVIEW ARTICLE Andrew David Naselli and Charles Naselli Andy Naselli (PhD, Bob Jones University; PhD, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) is Research Manager for D. A. Carson, Administrator of Themelios, and adjunct faculty at several seminaries. Charles Naselli, Andy’s father, is founder and President of Global Recruiters of Greenville in South Carolina. He has been an engineer, corporate executive, and entrepreneur, and has had an abiding interest in politics since the early 1970s. Wayne Grudem. Politics—According to the Bible: A Comprehensive Resource for Understanding Modern Political Issues in Light of Scripture. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010. 619 pp. $39.99. Carl R. Trueman. Republocrat: Confessions of a Liberal Conservative. Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian & Reformed, 2010. xxvii + 110 pp. $9.99. Michael Gerson and Peter Wehner. City of Man: Religion and Politics in a New Era. Edited by Timothy Keller and Collin Hansen. Cultural Renewal. Chicago: Moody, 2010. 140 pp. $19.99. Evangelical publishers released three new books on politics this fall, and they are sure to stir up controversy. People will invariably react differently to them because people have diverse worldviews and life-experiences. If a man works all day in a cubicle next to obnoxious, non- intellectual, right-wing conspiracy-theorists whose primary source of political information comes from opinionators like Glenn Beck, he might be sick of politics and be tempted to vote Democrat in protest! On the other hand, if he rarely interacts with people like that and instead regularly reads the best of conservative politics (e.g., National Review), he might feel insulted when someone from the Left broadly attacks the entire Right without engaging the best conservative arguments (this partially explains our evaluation of Carl Trueman’s book!). -

Miller Center University of Virginia Cabinet Report 2016–2017

UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA MILLER CENTER STANDARD PRESORT P.O. Box 400406 US POSTAGE Charlottesville, VA 22904-4406 PAID millercenter.org CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA PERMIT No. 164 REVEALINGCABINET REPORT 2016–2017 MILLER CENTER UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA DEMOCRACY CONTENTS FROM THE DIRECTORS ……………………………………… 3 EVENT LISTINGS FIRST YEAR …………………………………………………… 4 GREAT ISSUES ……………………………………………… 6 HISTORICAL PRESIDENCY ……………………………… 6 OTHER EVENTS ……………………………………………… 7 AMERICAN FORUM ………………………………………… 8 IN THE MEDIA ………………………………………………… 12 FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES AND ASSETS ……………… 14 PHILANTHROPIC SUPPORT ……………………………… 16 SCHOLARS AND STAFF …………………………………… 21 GOVERNING COUNCIL …………………………………… 22 ON THE COVER – BACKGROUND IMAGE MILLER CENTER FOUNDATION BOARD …………… 22 Ramón de Elorriaga. General Washington Delivering His THE HOLTON SOCIETY ……………………………………… 22 Inaugural Address to New York, April 30, 1789. 1899. Oil MILLER CENTER, BY THE NUMBERS………………… 23 on canvas. Federal Hall National Memorial, New York City. FROM THE DIRECTORS Dear Friend of the Miller Center: In this era of bitter partisanship, our work studying the American presidency has never been more important. We mine the lessons of history to provide a nonpartisan foundation on which public policy can be built—bringing our discoveries to the media, scholars, and key presidential infl uencers on both sides of the political aisle. And we bring our insights directly to interested citizens, through our website, electronic newsletters, public events, and social media. Our commitment to high-quality presidential research -

Exvangelical: Why Millennials and Generation Z Are Leaving the Constraints of White Evangelicalism

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 2-2020 Exvangelical: Why Millennials and Generation Z are Leaving the Constraints of White Evangelicalism Colleen Batchelder Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin Part of the Christianity Commons GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY EXVANGELICAL: WHY MILLENNIALS AND GENERATION Z ARE LEAVING THE CONSTRAINTS OF WHITE EVANGELICALISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY COLLEEN BATCHELDER PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY 2020 Portland Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Colleen Batchelder has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on February 20, 2020 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Global Perspectives Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Karen Tremper, PhD Secondary Advisor: Randy Woodley, PhD Lead Mentor: Jason Clark, PhD, DMin Copyright © 2020 by Colleen Batchelder All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY .................................................................................................................. vi ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... x CHAPTER 1: GENERATIONAL DISSONANCE AND DISTINCTIVES WITHIN THE CHURCH ....................................................................................................................... -

The Spirit of Liberty: at Home, in the World

A CALL TO ACTION THE SPIRIT OF LIBERTY: AT HOME, IN THE WORLD BY THOMAS O. MELIA AND PETER WEHNER FOR THE GEORGE W. BUSH INSTITUTE THE SPIRIT OF LIBERTY: AT HOME, IN THE WORLD A Call to Action By Thomas O. Melia and Peter Wehner For the George W. Bush Institute Human Freedom Initiative Copyright The George W. Bush Institute 2017, all rights reserved. The Bush Institute engaged research fellows to develop ideas and options for how to affirm American values of freedom and free markets, fortify the institutions that secure st these values at home, and catalyze a 21 century consensus that it is in America’s interest to lead in their strengthening worldwide. For requests and information on this report, please contact: The George W. Bush Institute [email protected] www.bushcenter.org 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 THE CHALLENGE 6 A CALL TO ACTION 13 HARDEN OUR DEFENSES 16 PROJECT AMERICAN LEADERSHIP 22 STRENGTHEN THE AMERICAN CITIZEN 33 RESTORE TRUST IN DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS 39 CONCLUSION 50 2 INTRODUCTION This Call to Action is part of a major The premise of all that follows is that new effort of the George W. Bush the unique promise of America and Institute’s Human Freedom Initiative. the source of its greatest strengths is It seeks in a bipartisan way to affirm its commitment to a particular vision American values of freedom broadly of the human good. That vision understood, to fortify the institutions begins from the free and equal that secure these values at home, individual, endowed by our Creator and to help catalyze a 21st century with the rights to life, liberty, and the consensus that it is in America’s pursuit of happiness. -

Enterprise Report Restoring Liberty, Opportunity, and Enterprise in America

Issue No. 1, Winter 2020 Enterprise Report Restoring Liberty, Opportunity, and Enterprise in America A New Year and New Opportunities By AEI President Robert Doar A new year offers the opportunity to set priorities. Our highest priorities at AEI come from our institutional commitment to freedom: We believe in free people, free markets, and limited government. We promote the rule of law, economic opportunity for all, and institutions of civil society that make our freedom possible. And we stand for a strong American role in the world. These priorities guide how we want our scholarship to move the public debate; they relate to our philosophical predisposition. And they are well-known. Lately, I have been thinking about two other priorities that are less discussed but vitally important to the Institute and our scholars’ work. These two priorities are not so much about where we want our country to be headed but rather how we want to do our research—the intellectual environment AEI must foster so that our scholars can do their best and most effective work. That intellectual environment must be grounded in two simple values: independence of thought and the competition of ideas. So long as they remain consistent with our overarching philosophy and maintain high standards of quality, our scholars engage in their work free of control from anyone, including management. Within their areas of expertise, our scholars study, write, and say what they want to study, write, and say. We recruit great thinkers and writers with established records, and we give them the freedom to apply their skills however they see fit. -

Digital Demagogue: the Critical Candidacy of Donald J. Trump

Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, Vol. 6, No.3/4, 2016, pp. 62-73. Digital Demagogue: The Critical Candidacy of Donald J. Trump Amy E. Mendes Over the last several months, businessperson Donald Trump has taken the lead in the Republican primary race. His flamboyant personality and unusually aggressive speech has drawn much attention and criticism. Journalists and academics have posited that Trump’s rhetoric is that of a demagogue. This essay catalogues the existing definitions of demagoguery, examines how Trump’s rhetoric may qualify, and outlines some ways in which demagogues may function differently in a digital world. Keywords: digital demagogue, election, rhetoric, scapegoat, xenophobia The long road to businessperson Donald Trump’s nomination as the presidential candidate for the Republican party has drawn much attention from rhetorical scholars. His flamboyant personality and unusually aggressive speech have prompted both journalists and academics to label him a demagogue. If this assessment is accurate, Trump may be positioned to become the latest in a category of leaders who have historically left devastating legacies. However, accusations of dem- agoguery should not be made lightly, as they may be used to silence or discredit marginalized voices.1 Since having a demagogue in the office of President would be disastrous, the question of determining whether his rhetoric fits the description is an important one. Even if Trump’s bid is unsuccessful, his campaign is raising issues and lines of argument that have not previously been associated with presidential campaign rhetoric, or even with polite society. Roberts-Miller has described how argument and ideology can both shape policy and influence individual behavior.2 In the digital age, a demagogue has the capacity to reach more people than ever before, as the internet serves as both the catalyst and the cauldron in the creation of a movement.