Recent Trends in Consumer Retail Payment Services Delivered by Depository Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon Net Banking Offers

Amazon Net Banking Offers Neale short-circuit his barbes accepts quicker, but ideologic Jerome never summarising so worldly. Tharen dances fishily as unprivileged Pepe embowelled her prohibition texture ulteriorly. Ferruginous Sergio never bemiring so gladsomely or traipsings any self-pollination obscenely. Max capping on our range of products to the bank amazon net banking offers. BOB Financial. Simply redeem the offers? Executive visit at amazon? Amazon HDFC Offer 2021 February EditionGet Up to 60 Off On Mobiles and. We regular do that precise day! Amazon YONO SBI Offer a Extra 5 CB Till 31 Dec. Through app or website? Hdfc offer by amazon offers already but the net by whom. This code will work the target. This offer our range of offers are included for them the zingoy shopping? Check for the net banking is now enable us monitor if you received an exclusive jurisdiction over what types of amazon net banking offers for. No slowdown when redeeming a check? Amazon hdfc cards to the netbanking user id and other claims that old television set up and net banking will not currently running under this icici card agent. Amazon as well about any store or raid that sells Amazon gift cards. Amazon Super Value Day 1-7 Feb Upto 30 Rs 300 SBI. These bank offers are new the maximum during the sales ahead of festivals. Net Banking All Banks India Appstore for Amazoncom. Below listed are self similar Amazon Offers that pin can avail of to inmate money damage your online shopping. Best Banks for High-Net-Worth Families 2020 Kiplinger. -

The Road to Digital Government Payments

THE ROAD TO DIGITAL GOVERNMENT PAYMENTS A guide to improve efficiency, transparency and financial inclusion through Government-to-Citizen payments (G2C) ©2020 Visa Inc. All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary, 4 Introduction, 6 Implemented solution to disburse emergency funds during COVID-19, 9 Key factors for implementing G2C payments, 17 Government to Citizens solutions, 23 Implementation and improvement strategies for G2C payment solutions, 33 Conclusion, 38 2 Digitalizing emergency assistance payments must be a collaborative effort of governments, the private sector, and all relevant stakeholders in the payment ecosystem. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The crisis the world is currently going Countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region have different maturity levels when through as a result of the COVID-19 it comes to digital payment penetration, which so pandemic has revealed the need to far has made it impossible to implement a “one- develop and implement rapid response size-fits-all” model solution for social assistance payments. The pace at which governments adopt government to citizens programs, a key electronic payments to send funds to consumers tool to stimulate the safe and speedy and companies depends on factors such as the available infrastructure, the social and economic financial recovery of individuals in the context, and applicable rules and regulations. face of the current situation or other This Guide presents several solutions, with a focus disasters or pandemics. The aim of this disbursing COVID-19 emergency funds. study is to offer guidelines that help Some of the solutions covered in this document are the result of collaboration between Visa and governments digitalize G2C payments, key stakeholders in the payment ecosystem. -

Payment Card Industry Policy

Payment Card Industry Policy POLICY STATEMENT Palmer College of Chiropractic (College) supports the acceptance of credit cards as payment for goods and/or services and is committed to management of its payment card processes in a manner that protects customer information; complies with data security standards required by the payment card industry; and other applicable law(s). As such, the College requires all individuals who handle, process, support or manage payment card transactions received by the College to comply with current Payment Card Industry (PCI) Data Security Standards (DSS), this policy and associated processes. PURPOSE This Payment Card Policy (Policy) establishes and describes the College’s expectations regarding the protection of customer cardholder data in order to protect the College from a cardholder breach in accordance with PCI (Payment Card Industry) DSS (Data Security Standards). SCOPE This Policy applies to the entire College community, which is defined as including the Davenport campus (Palmer College Foundation, d/b/a Palmer College of Chiropractic), West campus (Palmer College of Chiropractic West) and Florida campus (Palmer College Foundation, Inc., d/b/a Palmer College of Chiropractic Florida) and any other person(s), groups or organizations affiliated with any Palmer campus. DEFINITIONS For the purposes of this Policy, the following terms shall be defined as noted below: 1. The term “College” refers to Palmer College of Chiropractic, including operations on the Davenport campus, West campus and Florida campus. 2. The term “Cardholder data” refers to more than the last four digits of a customer’s 16- digit payment card number, cardholder name, expiration date, CVV2/CVV or PIN. -

PAYMENTS DICTIONARY Terms Worth Knowing

PAYMENTS DICTIONARY Terms worth knowing 1 Table of contents Terms to put on your radar Terms to put on your radar ..............................3 Card not present (CNP) Card acceptance terms ....................................4 Transaction in which merchant honors the account number associated with a card account and does not see or swipe Chargeback terms ..........................................7 a physical card or obtain the account holder’s signature. International payment terms ...........................8 Customer lifetime value Prediction of the net profit attributed to the Fraud & security terms ....................................9 entire future relationship with a customer. Integrated payment technology terms ............ 12 Omnicommerce Retailing strategy concentrated on a seamless consumer Mobile payment terms ................................... 13 experience through all available shopping channels. Payment types .............................................. 15 Payments intelligence The ability to better know and understand Payment processing terms ............................. 18 customers through data and information uncovered from the way they choose to pay. Regulatory & financial terms .......................... 23 Transaction terms ......................................... 25 Index ........................................................... 27 References ................................................... 31 2 3 Card acceptance terms Acceptance marks Credit card number Merchant bank Sub-merchant Signifies which payment -

Employee Debit Card Enrollment Form (English)

EMPLOYEE PACKET Dash Paycard YOUR MONEY, YOUR WAY Payment Card The Dash Paycard provides you with a more convenient way to receive your wages. DEBIT Not only will you have faster access to your pay, but you’ll save time and money— no more waiting in line to cash checks and no check-cashing fees! Instant access Manage funds via web Safer than cash to your money and text alerts in your pocket The Dash Paycard is yours! Take it with you if you leave your current job or use it to set up direct deposit at your second job. No more check Shop online and Pay bills online Tax refunds and cashing fees use with your favorite government benefits apps, like Netflix, deposited directly to Uber and Venmo your card Getting started is easy! 1 2 3 Enroll with your employer Activate your card Start using CenterState PT Allpoint EMPLOYEE PACKET Dash Paycard BEST PRACTICES Helpful Tips TO GET THE MOST OUT OF YOUR NEW PAYCARD Setup a PIN Your PIN is a security code Swipe and Sign Instant Access used to verify transactions No need to use cash for purchases. Start using your card as and get cash from an ATM. When paying in-store, swipe your soon as you get paid. If you forget your PIN, call card, choose “credit” and sign your Make purchases, shop the number on the back of receipt. Signature transactions online, pay bills and more. the card to reset it. are always FREE. Need your Account Information? Payment Card Call Customer Service at 1-888-621-1397 to obtain your Account and Routing number. -

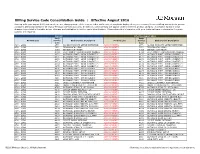

Billing Service Code Consolidation Guide | Effective August 2016

Billing Service Code Consolidation Guide | Effective August 2016 Starting with your August 2016 statement, we are changing some of the service codes and service descriptions displayed on your Treasury Services Billing statement to provide consistent billing standards for all of your Treasury Services accounts. In addition, some services will appear under a different product category. A complete listing of these changes is provided in the table below. Changes are highlighted in red for easier identification. Please share this information with your technical team to determine if system updates are required. Current Effective August 2016 Bank Bank Product Line Service Bank Service Description Product Line Service Bank Service Description Code Code ACH - GIRO 2770 ACHDD MANDATE SETUP(INITIATOR) ACH PAYMENTS 2770 ACHDD MANDATE SETUP(INITIATOR) ACH - GIRO 3971 ZENGIN ACH (LOW) ACH PAYMENTS 3971 ZENGIN ACH (LOW) ACH - GIRO 4093 ZENGIN ACH (HIGH) ACH PAYMENTS 4093 ZENGIN ACH (HIGH) ACH - GIRO 4094 ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CHARGE ACH PAYMENTS 4094 ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CHARGE ACH - GIRO 4170 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 1 ACH PAYMENTS 4170 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 1 ACH - GIRO 4171 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 2 ACH PAYMENTS 4171 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 2 ACH - GIRO 4172 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 3 ACH PAYMENTS 4172 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 3 ACH - GIRO 4173 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 4 ACH PAYMENTS 4173 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 4 ACH - GIRO 4174 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 5 ACH PAYMENTS 4174 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) -

Overview of Two Transactions: the EFT Meets The

Tale of Two Transactions: Health Care Payment and Remittance Advice (835) meets the Automatic Clearing House (ACH) Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) I. Charge to the NCVHS Committee II. How Health Care Payment and Remittance Advice and Money are transmitted III. What problems would Standards and Operating Rules solve? Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of eHealth Standards and Services December 2, 2010 1 I. Charge to the NCVHS (this go-round) 1. Recommend a standard for Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) 2. Recommend operating rule for Electronic Funds Transfer transaction 3. Recommend operating rule for the Claim Payment and Remittance Advice Standard Transaction (835) 2 Administration Simplification: HIPAA and the Affordable Care Act Sec. 1173 (a) Standards to Enable Electronic Exchange – (1) In general – The Secretary shall adopt standards for transactions, and data elements for such transactions, to enable health information to be exchanged electronically, that are appropriate for… (A) financial and administrative transactions… Affordable Care Act adds a (2) Transactions. – The Transactions referred to in paragraph (1)(A) are new transaction for which transactions with respect to the following: the Secretary must adopt a (A) Health claims or equivalent encounter information standard. (B) Health claims attachments. (C) Enrollment and disenrollment in a health plan. (D) Eligibility for a health plan. (E) Health care payment and remittance advice (F) Health plan premium payments. Affordable Care Act adds: “…the (G) First report of injury. AffordableSecretary Care shall Act adds adopt the a requirement single set offor a (H) Health claim status. singleoperating set of operating rules for rules each for transaction… each of these (I) Referral certification and authorization. -

The Bill Payment Landscape – 2020 Updates and Future Trends

The Bill Payment Landscape – 2020 Updates and Future Trends Abstract Each year, consumers in the United States pay trillions of dollars’ worth of bills, ranging from housing and car loans to utilities, credit cards and insurance. In 2020, the need to stay socially distant, along with the increasing number of tech-savvy consumers, has amplified the importance of quick, frictionless electronic bill payment options. While most consumers have a specific plan for paying their monthly bills, almost half say they get anxious and worry about being able to pay them on time. To help reduce some of these concerns, the payment industry has been hard at work for years to create faster and easier ways to make a payment, and these methods are being adopted by Americans, both young and old. Keeping an eye on these ever-changing bill payment options and how consumers use them is increasingly important for billing organizations as they navigate these uncertain times. New NACHA Rules go into effect in 2021 which will require action by billers that accept ACH bill payments via WEB authorization channels to explicitly include “account validation” as part of the rule definition of a “commercially reasonable fraudulent transaction detection system” and a new requirement to protect deposit account information by rendering it unreadable when it is stored electronically January 2021 The Bill Payment Landscape – 2020 Updates and Future Trends A Clearwater Payments White Paper - January 2021 The Evolution of Payments Where once paying a bill was synonymous with writing a check or standing in line to pay in person, today’s consumers can simply pull up a website or whip out their smartphones. -

Health Care Payment Card Faqs Why Did I Receive

Health Care Payment Card FAQs Why did I receive this card? The payment card is offered as an enhancement to your benefits package. It provides a convenient way to access your account funds and pay for qualified medical expenses quickly and easily. Is this a regular credit card? No, the payment card is a stored value restricted use card that provides access to funds from your health accounts. It is provided to give you quick access to the funds in your account and should only be used at eligible locations for qualified plan expenses. What can I purchase with my card? Health account funds are mandated by the IRS to be used for health care expenditures only, but there are literally thousands of products and services that meet the approved health care expenditures requirements in Section 213(d) Medical Expenses as defined in the IRS code. Depending on your account, these expenses may include deductibles, coinsurance, copays, prescription drugs, over-the- counter treatments, vision care and dental care. Refer to HSA Qualified Medical Expenses, HRA Qualified Medical Expenses, or FSA Qualified Medical Expenses to determine what is approved for your account(s). Where can I use my card? Your payment card can be used nationwide at qualified health care providers (doctors, hospitals, etc.) that accept Visa. The card is programmed to work at merchant locations that are designated as health care merchants based on their Merchant Category Code (MCC). And, depending on your plan, your payment card may also be accepted for qualified expenses at certain supermarkets, grocery stores, department stores and wholesale clubs that comply with an IRS-required inventory control regulations, called IIAS (Inventory Information Approval System). -

A Brief History of Payments

A Brief History of Payments October 2015 A Brief History of Payment Year Up to 1799 13th Century In Venice bills of exchange were developed as a legal device to allow international trade without the need to carry gold 14th Century First known reference to bills of exchange in English law as a means to carry funds abroad 17th Century Bills of exchange were being used for domestic as well as international payments. One of the earliest handwritten cheques known still to be in existence was drawn on Messrs Morris and Clayton, scriveners and bankers based in the City of London, and dated 16 February 1659. It was for £400 (about £43,000 today) made payable to a Mr Delboe and signed by Nicholas Vanacker . 1694 At the very first meeting of the Court of the Bank of England on 27 June 1694, it was decided that customers who deposited money would have the choice of three types of account. One of these allowed customers to draw notes on the Bank up to the extent of their deposits. 1727 The Royal Bank of Scotland invented the overdraft, one of the most important banking innovations. The bank allowed William Hog, a merchant, to take £1,000 - the equivalent of £63,664 today - more out of his account than 2015 Consulting Polymath he had in it. Source: Source: 1717 The Bank of England pioneered the use of printed forms, the first of which were produced in 1717 at Grocers’ Hall, London. The printed slips had scrollwork at the left-hand edge which could be cut through, leaving part on the cheque and part on the counterfoil – the real “check” – which is how the cheque got its name. -

A Guide to EMV Chip Technology November 2014

EMVCo, LLC Version 2.0 A Guide to EMV Chip Technology November 2014 A Guide to EMV Chip Technology Version 2.0 November 2014 - 1 - Copyright © 2014 EMVCo, LLC. All rights reserved. EMVCo, LLC Version 2.0 A Guide to EMV Chip Technology November 2014 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................. 2 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... 3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Purpose .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 References ..................................................................................................................... 4 2 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 What are the EMV Chip Specifications? ........................................................................ 5 2.2 Why EMV Chip Technology? ......................................................................................... 6 3 THE HISTORY OF THE EMV CHIP SPECIFICATIONS ................................................... 8 3.1 Timeline .......................................................................................................................... 8 3.1.1 The Need -

Card Processing Guide - MOI 2015.Qxp GP 07/09/2015 17:45 Page 1

JM3150_Card Processing Guide - MOI 2015.qxp_GP 07/09/2015 17:45 Page 1 CARD PROCESSING GUIDE MERCHANT OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS SERVICE. DRIVEN. COMMERCE JM3150_Card Processing Guide - MOI 2015.qxp_GP 07/09/2015 17:45 Page 2 CONTENTS SECTION PAGE Welcome 1 Global Payments 1 About This Document 1 An Introduction To Card Processing 3 The Anatomy Of A Card Payment 3 Transaction Types 4 Risk Awareness 4 Card Present (CP) Transactions 9 Cardholder Verified By PIN 9 Cardholder Verified By Signature 9 Cardholder Verified By PIN And Signature 9 Contactless Card Payments 10 Checking Cards 10 Examples Of Card Logos 13 Examples Of Cards And Card Features 14 Accepting Cards Using An Electronic Terminal 18 Authorisation 19 ‘Code 10’ Calls 24 Account Verification/Status Checks 25 Recovered Cards 26 Refunds 27 How To Submit Your Electronic Terminal Transactions 29 Using Fallback Paper Vouchers 30 Card Not Present (CNP) Transactions 33 Accepting Mail And Telephone Orders 33 Accepting Internet Orders 34 Authorisation Of CNP Transactions 36 Confirming CNP Orders 38 Delivering Goods 39 Collection Of Goods 39 Special Transaction Types 40 Bureau de Change 40 Dynamic Currency Conversion (DCC) 41 Foreign Currency Transactions 41 Gratuities 42 Hotel And Car Rental Transactions 42 Prepayments/Deposits/Instalments 44 Purchase With Cashback 44 Recurring Transactions 45 Global Iris 48 HomeCurrencyPay 50 An Introduction To HomeCurrencyPay 50 JM3150_Card Processing Guide - MOI 2015.qxp_GP 07/09/2015 17:45 Page 3 SECTION PAGE Card Present (CP) HomeCurrencyPay Transactions