A Vision for Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Open Door Today! (PDF)

disabilityequality.scot ISSUE 56 | 2021 Welcome to the latest issue of OPEN DOOR, the quarterly magazine from Disability Equality Scotland OPEN DOOR Disability News and Views for Disabled People Across Scotland Issue 56: Embedding Inclusive Communication in Recovery Your Disability, Your Voice, Your Scotland… Disability Equality Scotland is a member led organisation, so we want to hear from you, our valued members! Get in touch with us with your disability news by email at: [email protected] or by calling on 0141 370 0968 Page Number 2 Contents 3 CEO’s Welcome: Introduction by Morven Brooks Inform 4 About Us 5-6 Our Team 7-10 Our Directors 11-12 National Hate Crime Charter Launched 13 Safe and Inclusive Ferries for All 14 Face Covering Exemption Card: Project Update 15-16 Scottish Parliament Election 2021: Manifesto Tracker 17-19 Information Hubs Support 20-22 Disability Equality Scotland: Why You Should Use Easy Read 23-24 Sense Scotland 25 Dyslexia Scotland 26-27 Charities Call for Action On Sensory Poverty 28-29 Scottish Commission for People with Learning Disabilities (SCLD) 30-31 OneBanks Your Say on Disability 32 About Your Say on Disability 33-34 Weekly Poll Roundup 35 Scottish Parliament Election 2021: Disability Hustings 36-37 Scottish Parliament Election 2021: Emma Roddick MSP 38 Webinar: Journey Planning, 24 May 2021 39 Webinar: Access to Public Appointments, 3 June 2021 Access Panel Network 40-41 About the Access Panel Network 42-43 Access Panel Conference 2021 44-47 Access Panel Network News 2 | Issue 56 - 2021 CEO’s Welcome Dear Member Welcome to another jam-packed edition of our Open Door magazine! One of our key commitments at Disability Equality Scotland is to raise awareness of inclusive communication, which is the theme for this edition of Open Door. -

Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 26 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 23 June 2021 Tuesday 31 August 2021 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by First Minister’s Statement: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Committee Announcements followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 1 September 2021 2:00 pm Parliamentary Bureau Motions 2:00 pm Portfolio Questions followed by Scottish Government Debate: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions -

Current Msps by NHS Board

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 13 May 2021 Updated: 16:00 Current MSPs by NHS Board This Fact Sheet lists all current Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who represent constituencies or regions within the boundaries of each of the NHS Boards in Scotland. The NHS Boards are listed in alphabetical order, followed by the name of the MSPs, their party and the constituency (C) or region (R) they represent. Party Abbreviation Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA Ayrshire and Arran Siobhian Brown (SNP) Ayr (C) Elena Whitham (SNP) Carrick, Cumnock and Doon Valley (C) Kenneth Gibson (SNP) Cunninghame North (C) Ruth Maguire (SNP) Cunninghame South (C) Willie Coffey (SNP) Kilmarnock and Irvine Valley (C) Current MSPs by NHS Board 1 Sharon Dowey (Con) South Scotland (R) Emma Harper (SNP) South Scotland (R) Craig Hoy (Con) South Scotland (R) Carol Mochan (Lab) South Scotland (R) Colin Smyth (Lab) South Scotland (R) Martin Whitfield (Lab) South Scotland (R) Brian Whittle (Con) South Scotland (R) Neil Bibby (Lab) West Scotland (R) Katy Clark (Lab) West Scotland (R) Russell Findlay (Con) West Scotland (R) Jamie Greene (Con) West Scotland (R) Ross Greer (Green) West Scotland (R) Pam Gosal (Con) West Scotland (R) Paul O'Kane (Lab) West Scotland (R) Borders Rachael Hamilton (Con) Ettrick, Roxburgh and Berwickshire (C) Christine Grahame (SNP) Midlothian South, Tweeddale and Lauderdale -

2021 MSP Spreadsheet

Constituency MSP Name Party Email Airdrie and Shotts Neil Gray SNP [email protected] Coatbridge and Chryston Fulton MacGregor SNP [email protected] Cumbernauld and Kilsyth Jamie Hepburn SNP [email protected] East Kilbride Collette Stevenson SNP [email protected] Falkirk East Michelle Thomson SNP [email protected] Falkirk West Michael Matheson SNP [email protected] Hamilton, Larkhall and Stonehouse Christina McKelvie SNP [email protected] Motherwell and Wishaw Clare Adamson SNP [email protected] Uddingston and Bellshill Stephanie Callaghan SNP [email protected] Regional Central Scotland Richard Leonard Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Monica Lennon Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Mark Griffin Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Stephen Kerr Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Graham Simpson Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Meghan Gallacher Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Gillian Mackay Green [email protected] Constituency MSP Name Party Email Glasgow Anniesland Bill Kidd SNP [email protected] Glasgow Cathcart James Dornan SNP [email protected] Glasgow Kelvin Kaukab Stewart SNP [email protected] Glasgow Maryhill and Springburn Bob Doris SNP [email protected] -

Meeting of the Parliament (Hybrid)

Meeting of the Parliament (Hybrid) Tuesday 1 June 2021 Session 6 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Tuesday 1 June 2021 CONTENTS Col. TIME FOR REFLECTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 COVID-19 .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Statement—[The First Minister]. The First Minister (Nicola Sturgeon) ............................................................................................................. 3 NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE RECOVERY PLAN .................................................................................................. 25 Motion moved—[Humza Yousaf]. Amendment moved—[Annie Wells]. Amendment moved—[Jackie Baillie]. The Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care (Humza Yousaf) ......................................................... 25 Annie Wells (Glasgow) (Con) ..................................................................................................................... 30 Jackie Baillie (Dumbarton) (Lab) ................................................................................................................ 33 Gillian Mackay (Central Scotland) (Green) ................................................................................................ -

Official Report Is Accurate

Meeting of the Parliament (Hybrid) Thursday 17 June 2021 Session 6 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Thursday 17 June 2021 CONTENTS Col. FIRST MINISTER’S QUESTION TIME ..................................................................................................................... 1 Drug Deaths .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Covid-19 (Personal Protective Equipment) .................................................................................................. 5 Climate Targets ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Covid-19 (Business Support) ...................................................................................................................... 11 Malicious Prosecutions (Inquiry) ................................................................................................................. 12 Psychiatric Hospitals (Discharge Delays) ................................................................................................... 13 Removal of Dental Charges ....................................................................................................................... 14 ScotRail Strike Action ................................................................................................................................ -

Official Reporter, It Is a Homecoming of Sorts

Meeting of the Parliament (Hybrid) Tuesday 15 June 2021 Session 6 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Tuesday 15 June 2021 CONTENTS Col. TIME FOR REFLECTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 POINT OF ORDER ............................................................................................................................................... 3 TOPICAL QUESTION TIME ................................................................................................................................... 4 Automated External Defibrillators (Amateur Sports Grounds) ..................................................................... 4 Racism in Schools ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Ferguson Marine Engineering Ltd ................................................................................................................ 8 COVID-19 ........................................................................................................................................................ 12 Statement—[First Minister]. The First Minister (Nicola Sturgeon) .......................................................................................................... -

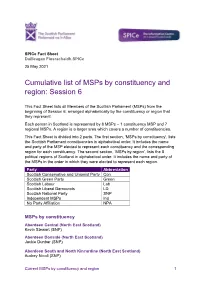

Cumulative List of Msps by Constituency and Region: Session 6

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 25 May 2021 Cumulative list of MSPs by constituency and region: Session 6 This Fact Sheet lists all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) from the beginning of Session 6, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represent. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a number of constituencies. This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSP elected to represent each constituency and the corresponding region for each constituency. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs in the order in which they were elected to represent each region. Party Abbreviation Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA MSPs by constituency Aberdeen Central (North East Scotland) Kevin Stewart (SNP) Aberdeen Donside (North East Scotland) Jackie Dunbar (SNP) Aberdeen South and North Kincardine (North East Scotland) Audrey Nicoll (SNP) Current MSPs by constituency and region 1 Aberdeenshire East (North East Scotland) Gillian Martin (SNP) Aberdeenshire West (North East Scotland) Alexander Burnett (Con) Airdrie -

Monday 5 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 5 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Change to membership of the Parliamentary Bureau The Presiding Officer wishes to inform Members that Gillian Mackay has replaced Patrick Harvie as the representative for the Scottish Green Party on the Parliamentary Bureau. Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 23 June 2021 Tuesday 31 August 2021 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by First Minister’s Statement: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Committee Announcements followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 1 -

Free Church of Scotland

THE PRINCIPAL ACTS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND CONVENED AT EDINBURGH MAY 2015 WITH THE MINUTES OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THAT ASSEMBLY AND THE MINUTES OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMISSION OF THE PREVIOUS ASSEMBLY FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND, THE MOUND, EDINBURGH (Scottish Charity Number: SC012925) MMXV 2015] THE FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND 1 INDEX 2015 PAGE PAGE A H Accounts Home Missions Board Appendix Report 65, 129 Acts, Principal 5 Supplementary Report: Assembly Clerks’ Office Youth 54, 62 Report 32, 90 Supplementary Report: Assistant Clerk, Presentation to 53 Ecumenical Relations 74 Appointments 90 B I Board of Ministry International Missions Board Report 82, 148 Report 89, 173 Board of Trustees Report 36, 105 L Supplementary Report Appointment of Assistant Clerk 52 Letters 34 Lord High Commissioner - visit 89 C Loyal and Dutiful Address Committee Appointed 32 Commission of Assembly Report 35 Acts 23 Lyle Orr Prize-winners 62 Appointed 92 Minutes 178 M D Minutes of the Proceedings 30 Moderator Deceased Ministers and Elders Elected 32 Committee to prepare Minute Address 35 Appointed 32 Report 92 N Delegates 53, 72, 89 Development Officer’s Report 140 North American Synod Report 90 E P Edinburgh Theological Seminary Board Report 77,162 Petition Supplementary Report: Rev. Ruairdh MacLean 63 Appointment of Principal 79 Presbytery: Inverness, Lochaber and Ross Principal’s Report 164 Union of Kilmorack and Kiltarlity 80 Psalmody and Praise Committee G Report 63, 145 General Assembly of 2016 appointed 93 2 ACTS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF [2014 PAGE R Representatives from Other Churches 32, 65 Roll of Assembly 30 S Standing Orders 205 V Visitation of Records Committee Appointed 32 Report 91 2015] THE FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND 3 CONTENTS 2015 ______________________________________________________________________________________________ CLASS I – ACTS THAT HAVE PASSED THE BARRIER ACT None CLASS II – ACTS THAT ARE OF GENERAL INTEREST TO THE CHURCH 1. -

Inverness Half Marathon RESULT 12Th March 2017

Inverness Half Marathon RESULT 12th March 2017 Gender Class Chip Chip Pos. Bib Time Name Team Gender Class Pos Pos Time Pos 1 11 1:06:48 Weynay Ghebresilasie Shettleston Harriers Male 1 MOPEN 1 1:06:48 1 2 8 1:08:11 Mark Mitchell Forres Harriers Male 2 MOPEN 2 1:08:11 2 3 5 1:08:37 Kenny Wilson Moray Road Runners Male 3 MOPEN 3 1:08:37 3 4 1731 1:08:57 Michael Wright Central AC Male 4 MOPEN 4 1:08:57 4 5 2014 1:10:50 Matthew Sutherland Central AC Male 5 MOPEN 5 1:10:50 5 6 235 1:12:24 Gordon Lennox Inverness Harriers AAC Male 6 MOPEN 6 1:12:23 6 7 1890 1:12:47 Michael O'Donnell Inverness Harriers AAC Male 7 MOPEN 7 1:12:47 7 8 2235 1:13:07 Joshua Mcgettigan Male 8 MOPEN 8 1:13:06 8 9 1412 1:13:29 Iain Macdonald Edinburgh AC Male 9 MOPEN 9 1:13:28 9 10 2382 1:13:58 Graham Bee Inverness Harriers AAC Male 10 MOPEN 10 1:13:58 10 11 1800 1:14:12 Sam Hesling Highland Hill Runners Male 11 MOPEN 11 1:14:12 11 12 1590 1:14:15 Richard Meade Edinburgh AC Male 12 MOPEN 12 1:14:15 12 13 2292 1:15:30 Wayne Dashper Forres Harriers Male 13 M40+ 1 1:15:30 13 14 541 1:15:45 Euan Webster Aberdeen AAC Male 14 MOPEN 13 1:15:44 14 15 1749 1:15:48 Iain Carroll Giffnock North AAC Male 15 MOPEN 14 1:15:47 15 16 2445 1:15:49 Kevin Cormack North Highland Harriers Male 16 M40+ 2 1:15:47 16 17 1367 1:15:54 Tom Roche Insch Trail Running Club Male 17 M40+ 3 1:15:53 17 18 1424 1:16:25 Roger Clark PH Racing Club Male 18 M40+ 4 1:16:23 18 19 1833 1:16:36 Billy Gibson Dundee Hawkhill Harriers Male 19 M40+ 5 1:16:35 19 20 23 1:17:56 Fionnuala Ross Shettleston Harriers Female -

![Official Report, 26 May 2021; C 9.] the Presiding Officer (Alison Johnstone): in That Spirit, Will She Set out the Specific Progress Good Afternoon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0079/official-report-26-may-2021-c-9-the-presiding-officer-alison-johnstone-in-that-spirit-will-she-set-out-the-specific-progress-good-afternoon-4590079.webp)

Official Report, 26 May 2021; C 9.] the Presiding Officer (Alison Johnstone): in That Spirit, Will She Set out the Specific Progress Good Afternoon

Meeting of the Parliament (Hybrid) Thursday 27 May 2021 Session 6 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Thursday 27 May 2021 CONTENTS Col. FIRST MINISTER’S QUESTION TIME ..................................................................................................................... 1 Relationship with Business ........................................................................................................................... 1 Queen Elizabeth University Hospital ............................................................................................................ 5 Freedom to Crawl Campaign ........................................................................................................................ 8 Trade Deal (Australia) ................................................................................................................................ 11 Incinerators (Moratorium) ........................................................................................................................... 12 Education (Support for Teachers) .............................................................................................................. 13 Lord Advocate and Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (Reform) ................................................ 14 Pladis McVitie’s (Proposed Factory Closure) ............................................................................................