Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaur Fever – Sinclair's Icon Reprinted with Permission from The

Reprinted with permission from the American Oil & Gas Historical Society http://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/sinclair-dinosaur/ Dinosaur Fever – Sinclair’s Icon by Bruce Wells, Executive Director Formed by Harry F. Sinclair in 1916, Sinclair Oil is one of the oldest continuous names in the oil industry. The Sinclair dinosaur first appeared in 1930. “Dino” quickly became a marketing icon whose popularity with children – and educational value – remains to this day. The first Sinclair “Brontosaurus” trademark made its debut in Chicago during the 1933-1934 “Century of Progress” World’s Fair. Sinclair published a special edition newspaper, Big News, describing the exhibit. The first “Brontosaurus” trademark made its debut in Chicago during the 1933-1934 “Century of Progress” World’s Fair. The Sinclair dinosaur exhibit drew large crowds once again at the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition. Four years later, even more visitors marvelled at an improved 70-foot dinosaur in Sinclair’s “Dinoland Pavilion” at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair. Today known more correctly as Apatosaurus, in the 1960s a 70-foot “Dino” Sinclair’s green giant and his accompanying cast of Jurassic traveled more 10,000 miles through 25 states – stopping at shopping centers and other venues where children were introduced to the wonders of the buddies, including Triceratops, Stegosaurus, a duck-billed Mesozoic era courtesy of Sinclair Oil. Hadrosaurus, and a 20-foot-tall Tyrannosaurus Rex – were again a success, especially among young people. With $50 million in assets, Harry Ford Sinclair borrowed Although it was the first U.S. exposition to be based on the another $20 million and formed Sinclair Oil & Refining future, with an emphasis “the world of tomorrow,” the Sinclair Corporation on May 1, 1916. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

To Patent Damages? J

HOW RELEVANT IS JUSTICE CARDOZO'S “BOOK OF WISDOM” TO PATENT DAMAGES? J. Gregory Sidak | Columbia Science and Technology Law Review Document Details All Citations: 17 Colum. Sci. & Tech. L. Rev. 246 Search Details Jurisdiction: National Delivery Details Date: August 18, 2016 at 1:54 AM Delivered By: kiip kiip Client ID: KIIPLIB02 Status Icons: © 2016 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. HOW RELEVANT IS JUSTICE CARDOZO'S “BOOK OF..., 17 Colum. Sci. &... 17 Colum. Sci. & Tech. L. Rev. 246 Columbia Science and Technology Law Review Spring, 2016 Article HOW RELEVANT IS JUSTICE CARDOZO'S “BOOK OF WISDOM” TO PATENT DAMAGES? d1 J. Gregory Sidak a1 Copyright © 2016 by J. Gregory Sidak Section 284 of the Patent Act specifies that damages for patent infringement must be “adequate to compensate for the infringement, but in no event less than a reasonable royalty.” To determine a reasonable royalty, courts often rely on the hypothetical-negotiation framework, which aims to determine a royalty upon which the infringer and patent holder would have agreed, had they negotiated a license for the use of the patented technology immediately before the infringement began. Determining a reasonable royalty requires a court to return in time to the moment of the hypothetical negotiation and account for the limited information available to the parties at that time. That limited information would have affected the parties' negotiating positions and consequently the outcome of the hypothetical negotiation. Conversely, because the parties at the time of the hypothetical negotiation would not have known information that became available only after the infringement began, information that postdates the hypothetical negotiation would not have affected a hypothetically negotiated reasonable royalty. -

The Triple Crown (1867-2020)

The Triple Crown (1867-2020) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2020 Authentic (Sept. 5, 2020) f-Swiss Skydiver (Oct. 3, 2020) Tiz the Law (June 20, 2020) Authentic John Velazquez Robby Albarado Manny Franco Authentic Bob Baffert Kenny McPeek Barclay Tagg Spendthrift Farm, MyRaceHorse Stable, Madaket Stables & Starlight Racing Peter J. Callaghan Sackatoga Stable 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug -

Vol 34, No 1 (2014)

Reports of the National Center for Science Education is published by NCSE to promote the understanding of evolutionary sciences, of climate sciences, and of science as a way of knowing. Vol 34, No 1 (2014) A flower-like structure of Bennettiales, from the Sedgwick Museum's collection, Cambridge. © Verisimilus 2008. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. From Wikimedia. ISSN: 2159-9270 Table of Contents Features Yes, Bobby, Evolution is True! 3 Michael D Barton Louisiana’s Love Affair with Creationism 7 Barbara Forrest Harry Sinclair 15 Randy Moore Confessions of an Oklahoma Evolutionist: The Good, the Bad, and Ugly 18 Stanley A Rice Reviews Odd Couples • Daphne J Fairbairn 25 Robert M Cox The Spirit of the Hive • Robert E Page Jr 28 James H Hunt The Cambrian Explosion • Douglas H Erwin and James W Valentine 31 Roy E Plotnick The Social Conquest of Earth • Edward O Wilson 34 John H Relethford Relentless Evolution • John N Thompson 37 Christopher Irwin Smith Microbes and Evolution • edited by Roberto Kolter and Stanley Maloy 42 Tara C Smith ISSN: 2159-9270 2 Published bimonthly by the OF National Center for Science Education EPORTS THE NATIONAL CENTER FOR SCIEncE EDUCATION REPORTS.NCSE.COM R ISSN 2159-9270 FEATURE Yes, Bobby, Evolution is True! Joseph E Armstrong and Marshall D Sundberg Each fall the Botanical Society of America (BSA) issues a call for symposia to be held dur- ing the annual meeting the following summer. Every section of the society is encouraged to support one or more symposium proposals. Since the 2013 meeting was scheduled to be held in New Orleans, Louisiana, we thought that “teaching evolution” would be a good topical subject for a symposium that both the Historical and Teaching Sections could jointly support. -

January/February 1957

Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 Published t fomers a d o promote F . by the Lut/"ends and7en dship and G in Foundry ~ °r:: vance the ?Od Will With . ach in e Co Jn fe rest of its Jfs cus. LINE~~ .......... ~ ............ o~ ~v:· ~:· :"':P:a~n~y..: · :::::~: L:u~fk~~· P:r:od:u~c~.. ts~~ Sales and Service Offices of the LUFKIN FOUNDRY & J,BNUflRY • FEBRUARY. 1957 MACHINE COMPANY BAKERSFIELD. CALIFORNIA Volume 32 Number 1 2608 Pine St.; Phone Fflirview 7-8564 • Carl Frazer CASPER. WYOMING ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• P. 0. Box 1849. Phone 3-4670 Robert Bowcutt, Tom Berge CORPUS CHRISTI. TEXRS 1201 Wilson Bldg. ROCKY MOUNTAIN DIVISION ISSUE Phone TUiip 3-1881 fohn Swanson DALLAS. TExas COLORflDO'S MOUNTflIN MflJESTY 814 Vaughn Bldg. · Phone Riverside 8-5127 Dick Bellew and Bob flrrendale ..... 4- 7 A. £ . Ca raway-R. C. Thompson fim C. Roe DENVER. COLORADO 1423 Mile High Center NEW TRAILER SHOP IS COMPLETED ..... .. ... .. 8-11 Phone Alpine 5-1616 R. S. Miller EDMONTON. ALBERTA, CANADA LUFKIN INSTflLLflTIONS . ... .. .... .. ...... ... 12-13 Lufkin Machine Co., Ltd . 9950 Sixty-Fifth Ave., Phone 3-3111 Ja ck Gissler, Jack Leary, L. fl. Ruzicki EFFINGHAM. ILLINOIS CASPER'S TRflILS OF flDVENTURE 210 W. Jefferson St., Phone 667-W P. 0 . Box n Dolores B. Jeffords . ' .. ... ..... .. ' ' . 14-1 7 Lewis W. Breeden, Ben C. Sargent, Jr. EL DORADO. ARICANSAS f. R. Wilson Bldq. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Brookdale Farm Historic District Monmouth County, NJ Section Number 7 Page 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ` historic name Brookdale Farm Historic District other names/site number Thompson Park 2. Location street & number 805 Newman Springs Road not for publication city or town Middletown Township vicinity state New Jersey code NJ county Monmouth code 025 zip code 07738 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide locally. See continuation sheet for additional comments. -

SHPO Preservation Plan 2016-2026 Size

HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE COWBOY STATE Wyoming’s Comprehensive Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2016–2026 Front cover images (left to right, top to bottom): Doll House, F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Cheyenne. Photograph by Melissa Robb. Downtown Buffalo. Photograph by Richard Collier Moulton barn on Mormon Row, Grand Teton National Park. Photograph by Richard Collier. Aladdin General Store. Photograph by Richard Collier. Wyoming State Capitol Building. Photograph by Richard Collier. Crooked Creek Stone Circle Site. Photograph by Danny Walker. Ezra Meeker marker on the Oregon Trail. Photograph by Richard Collier. The Green River Drift. Photograph by Jonita Sommers. Legend Rock Petroglyph Site. Photograph by Richard Collier. Ames Monument. Photograph by Richard Collier. Back cover images (left to right): Saint Stephen’s Mission Church. Photograph by Richard Collier. South Pass City. Photograph by Richard Collier. The Wyoming Theatre, Torrington. Photograph by Melissa Robb. Plan produced in house by sta at low cost. HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE COWBOY STATE Wyoming’s Comprehensive Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2016–2026 Matthew H. Mead, Governor Director, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Milward Simpson Administrator, Division of Cultural Resources Sara E. Needles State Historic Preservation Ocer Mary M. Hopkins Compiled and Edited by: Judy K. Wolf Chief, Planning and Historic Context Development Program Published by: e Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Wyoming State Historic Preservation Oce Barrett Building 2301 Central Avenue Cheyenne, Wyoming 82002 City County Building (Casper - Natrona County), a Public Works Administration project. Photograph by Richard Collier. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................5 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................6 Letter from Governor Matthew H. -

SITEWIDE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT EA-1236 For

FINAL SITEWIDE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT EA-1236 for PREPARATION FOR TRANSFER OF OWNERSHIP OF NAVAL PETROLEUM RESERVE NO. 3 (NPR-3) Natrona County, Wyoming Prepared By U.S. Department of Energy Casper, Wyoming April 1998 - DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Preparation for Transfer of Ownership of Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3 AGENCY: Naval Petroleum and Oil Shale Reserves U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) ACTION: Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) for the Transfer of Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3 (DOE/EA-1236) SUMMARY: The Secretary of Energy is authorized to produce the Naval Petroleum Reserves No. 3 (NPR-3) at its maximum efficient rate (MER) consistent with sound engineering practices, for a period extending to Apr115 2000 subject to extension. Production at NPR-3 peaked in 1981 and has declined since until it has become a mature stripper field, with the average well yielding less than 2 barrels per day. The Department of Energy (DOE) has decided to discontinue Federal operation of NPR-3 at the end of its life as an economically viable oilfield currently estimated to be 2003. Although changes in oil and gas markets or shifts in national policy could alter the economic limit of NPR-3, it productive life will be determined largely by a small and declllng reserve base. DOE is proposing certain activities over the next six years in anticipation of the possible transfer of NPR-3 out of Federal operation. These activities would include the accelerated plugging and abandoning of uneconomic wells, complete reclamation and restoration of abandoned sites including dismantling surface facilities, batteries, roads, test satellites, electrical distribution systems and associated power poles, when they are no longer needed for production, and the continued development of the Rocky Mountain Oilfield Testing Center (RMOTC). -

2019 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 TABLE of CONTENTS

2019 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY 2 Table of Conents 3 General Information 4 History of The New York Racing Association, Inc. (NYRA) 5 NYRA Officers and Officials 6 Belmont Park History 7 Belmont Park Specifications & Map 8 Saratoga Race Course History 9 Saratoga Leading Jockeys and Trainers TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 10 Saratoga Race Course Specifications & Map 11 Saratoga Walk of Fame 12 Aqueduct Racetrack History 13 Aqueduct Racetrack Specifications & Map 14 NYRA Bets 15 Digital NYRA 16-17 NYRA Personalities & NYRA en Espanol 18 NYRA & Community/Cares 19 NYRA & Safety 20 Handle & Attendance Page OWNERS 21-41 Owner Profiles 42 2018 Leading Owners TRAINERS 43-83 Trainer Profiles 84 Leading Trainers in New York 1935-2018 85 2018 Trainer Standings JOCKEYS 85-101 Jockey Profiles 102 Jockeys that have won six or more races in one day 102 Leading Jockeys in New York (1941-2018) 103 2018 NYRA Leading Jockeys BELMONT STAKES 106 History of the Belmont Stakes 113 Belmont Runners 123 Belmont Owners 132 Belmont Trainers 138 Belmont Jockeys 144 Triple Crown Profiles TRAVERS STAKES 160 History of the Travers Stakes 169 Travers Owners 173 Travers Trainers 176 Travers Jockeys 29 The Whitney 2 2019 Media Guide NYRA.com AQUEDUCT RACETRACK 110-00 Rockaway Blvd. South Ozone Park, NY 11420 2019 Racing Dates Winter/Spring: January 1 - April 20 BELMONT PARK 2150 Hempstead Turnpike Elmont, NY, 11003 2019 Racing Dates Spring/Summer: April 26 - July 7 GENERAL INFORMATION GENERAL SARATOGA RACE COURSE 267 Union Ave. Saratoga Springs, NY, 12866 -

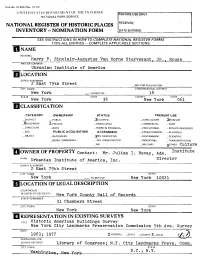

Hclassifi Cation

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STAThS DEPARTMENT OKI HE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE IN STRUCT IONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Harry P. Sinclair-Augustus Van Home Stuyvesant, Jr., House AND/OR COMMON Ukranian Institute of America LOCATION STREET& NUMBER «_ *_•«.« w i > v/ii i^w*vxvxw —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT New York _. VICINITY OF 18 CODE COUNTY CODE New York New York 061 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC — OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE Jfr/IUSEUM -JfeuiLDING(S) X_PR|VATE —UNOCCUPIED — COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS -JfES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY jyOTHER CultUl A (OWNER OF PROPERTY contact: Mr. Julian I. Revay, Adm. Institute NAME Urkanian Institute of America, Inc. Director STREET & NUMBER 2 East 79th Street CITY. TOWN STATE New York VICINITY OF New York 10021 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC New York County Hall of Records STREEF& NUMBER 31 Chambers Street CITY. TOWN STATE New York New York REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS F1TLE Historic American Buildings Survey New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission 5th Ave. Survey DATE 1963; 1977 X-FEDERAL _STATE COUNTY X-LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress; N.Y. City Landmarks Prevs. Comm. CITY. TOWN STATE Washington, New York B.C.; N.Y. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED JfcjNALTERED _J£)RIGINAL SITE vQOOD __RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR __UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE From 1918 to 1930, during the height of both his economic power and his period of disgrace, Harry F. -

2016 Natrona County Development Plan

2016 Natrona County Development Plan Purpose of the Development Plan The Natrona County Development Plan is an official guidance document adopted by the Board of County Commissioners as a policy guide for making decisions about the physical development of the County. It indicates how public officials and citizens desire the local area (referred to as the “planning area”) to develop in the future. It is an official statement of a governing body which outlines its major policies concerning future physical development. (For current zoning of a lot or parcel please refer to the Zoning Resolution of Natrona County). Natrona County has jurisdiction over land development on private lands and County owned lands in the unincorporated areas of the County, through zoning and subdivision regulations. In addition, there are critical relationships with the municipalities in the County and federal land managers that determine how land will be developed. It is the duty of Natrona County to administer its jurisdiction and relationships so that the people of Natrona County are able to use their land in a safe, effective manner, free from conflicts and in an economically viable fashion. It is the Board of County Commissioners duty to help insure that lands under County jurisdiction are sustained and provide a viable economic base for the County and its residents. The purpose of the County Development Plan is intended to: • Establish land use designations for the urban and rural areas of the County, so that the urban and rural communities can develop in a logical manner; • Establish land development policies so that the current zoning resolution and subdivision regulations can be updated and effectively administered; • Establish through the Goals, Policies, and Actions, in Chapter 2, a program for implementation of the plan and actions to develop a planning program in the County; • Establish interagency coordination between the County, municipalities, and other agencies; The plan is intended to be a living document.