To Patent Damages? J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaur Fever – Sinclair's Icon Reprinted with Permission from The

Reprinted with permission from the American Oil & Gas Historical Society http://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/sinclair-dinosaur/ Dinosaur Fever – Sinclair’s Icon by Bruce Wells, Executive Director Formed by Harry F. Sinclair in 1916, Sinclair Oil is one of the oldest continuous names in the oil industry. The Sinclair dinosaur first appeared in 1930. “Dino” quickly became a marketing icon whose popularity with children – and educational value – remains to this day. The first Sinclair “Brontosaurus” trademark made its debut in Chicago during the 1933-1934 “Century of Progress” World’s Fair. Sinclair published a special edition newspaper, Big News, describing the exhibit. The first “Brontosaurus” trademark made its debut in Chicago during the 1933-1934 “Century of Progress” World’s Fair. The Sinclair dinosaur exhibit drew large crowds once again at the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition. Four years later, even more visitors marvelled at an improved 70-foot dinosaur in Sinclair’s “Dinoland Pavilion” at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair. Today known more correctly as Apatosaurus, in the 1960s a 70-foot “Dino” Sinclair’s green giant and his accompanying cast of Jurassic traveled more 10,000 miles through 25 states – stopping at shopping centers and other venues where children were introduced to the wonders of the buddies, including Triceratops, Stegosaurus, a duck-billed Mesozoic era courtesy of Sinclair Oil. Hadrosaurus, and a 20-foot-tall Tyrannosaurus Rex – were again a success, especially among young people. With $50 million in assets, Harry Ford Sinclair borrowed Although it was the first U.S. exposition to be based on the another $20 million and formed Sinclair Oil & Refining future, with an emphasis “the world of tomorrow,” the Sinclair Corporation on May 1, 1916. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

The Triple Crown (1867-2020)

The Triple Crown (1867-2020) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2020 Authentic (Sept. 5, 2020) f-Swiss Skydiver (Oct. 3, 2020) Tiz the Law (June 20, 2020) Authentic John Velazquez Robby Albarado Manny Franco Authentic Bob Baffert Kenny McPeek Barclay Tagg Spendthrift Farm, MyRaceHorse Stable, Madaket Stables & Starlight Racing Peter J. Callaghan Sackatoga Stable 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug -

Vol 34, No 1 (2014)

Reports of the National Center for Science Education is published by NCSE to promote the understanding of evolutionary sciences, of climate sciences, and of science as a way of knowing. Vol 34, No 1 (2014) A flower-like structure of Bennettiales, from the Sedgwick Museum's collection, Cambridge. © Verisimilus 2008. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. From Wikimedia. ISSN: 2159-9270 Table of Contents Features Yes, Bobby, Evolution is True! 3 Michael D Barton Louisiana’s Love Affair with Creationism 7 Barbara Forrest Harry Sinclair 15 Randy Moore Confessions of an Oklahoma Evolutionist: The Good, the Bad, and Ugly 18 Stanley A Rice Reviews Odd Couples • Daphne J Fairbairn 25 Robert M Cox The Spirit of the Hive • Robert E Page Jr 28 James H Hunt The Cambrian Explosion • Douglas H Erwin and James W Valentine 31 Roy E Plotnick The Social Conquest of Earth • Edward O Wilson 34 John H Relethford Relentless Evolution • John N Thompson 37 Christopher Irwin Smith Microbes and Evolution • edited by Roberto Kolter and Stanley Maloy 42 Tara C Smith ISSN: 2159-9270 2 Published bimonthly by the OF National Center for Science Education EPORTS THE NATIONAL CENTER FOR SCIEncE EDUCATION REPORTS.NCSE.COM R ISSN 2159-9270 FEATURE Yes, Bobby, Evolution is True! Joseph E Armstrong and Marshall D Sundberg Each fall the Botanical Society of America (BSA) issues a call for symposia to be held dur- ing the annual meeting the following summer. Every section of the society is encouraged to support one or more symposium proposals. Since the 2013 meeting was scheduled to be held in New Orleans, Louisiana, we thought that “teaching evolution” would be a good topical subject for a symposium that both the Historical and Teaching Sections could jointly support. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Brookdale Farm Historic District Monmouth County, NJ Section Number 7 Page 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ` historic name Brookdale Farm Historic District other names/site number Thompson Park 2. Location street & number 805 Newman Springs Road not for publication city or town Middletown Township vicinity state New Jersey code NJ county Monmouth code 025 zip code 07738 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide locally. See continuation sheet for additional comments. -

2019 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 TABLE of CONTENTS

2019 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY 2 Table of Conents 3 General Information 4 History of The New York Racing Association, Inc. (NYRA) 5 NYRA Officers and Officials 6 Belmont Park History 7 Belmont Park Specifications & Map 8 Saratoga Race Course History 9 Saratoga Leading Jockeys and Trainers TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 10 Saratoga Race Course Specifications & Map 11 Saratoga Walk of Fame 12 Aqueduct Racetrack History 13 Aqueduct Racetrack Specifications & Map 14 NYRA Bets 15 Digital NYRA 16-17 NYRA Personalities & NYRA en Espanol 18 NYRA & Community/Cares 19 NYRA & Safety 20 Handle & Attendance Page OWNERS 21-41 Owner Profiles 42 2018 Leading Owners TRAINERS 43-83 Trainer Profiles 84 Leading Trainers in New York 1935-2018 85 2018 Trainer Standings JOCKEYS 85-101 Jockey Profiles 102 Jockeys that have won six or more races in one day 102 Leading Jockeys in New York (1941-2018) 103 2018 NYRA Leading Jockeys BELMONT STAKES 106 History of the Belmont Stakes 113 Belmont Runners 123 Belmont Owners 132 Belmont Trainers 138 Belmont Jockeys 144 Triple Crown Profiles TRAVERS STAKES 160 History of the Travers Stakes 169 Travers Owners 173 Travers Trainers 176 Travers Jockeys 29 The Whitney 2 2019 Media Guide NYRA.com AQUEDUCT RACETRACK 110-00 Rockaway Blvd. South Ozone Park, NY 11420 2019 Racing Dates Winter/Spring: January 1 - April 20 BELMONT PARK 2150 Hempstead Turnpike Elmont, NY, 11003 2019 Racing Dates Spring/Summer: April 26 - July 7 GENERAL INFORMATION GENERAL SARATOGA RACE COURSE 267 Union Ave. Saratoga Springs, NY, 12866 -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

TEAPOT DOME OILFIELD HAER WY-100 (Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3) HAER WY-100 (NPR-3) 7.25 miles northeast of Teapot Rock and 9 miles southeast of the intersection of Wyoming 259 and Wyoming 387 Midwest vicinity Natrona County Wyoming PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD INTERMOUNTAIN REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 12795 West Alameda Parkway Denver, CO 80228 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD TEAPOT DOME OILFIELD (Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3) (NPR-3) HAER No. WY-100 Location: 7.25 miles northeast of Teapot Rock and 9 miles southeast of the intersection of Wyoming 259 and Wyoming 387, Midwest Vicinity, Natrona County, Wyoming USGS GILLAM DRAW WEST, WY Quadrangle, UTM Coordinates: Center area of Teapot Dome Oilfield: 402676.3 E – 4793772.3 N. Present Owner/ Occupant: Present Owner is Natrona County Holding, LLC, and the occupant is Stranded Oil Resources Corporation, a subsidiary of Natrona County Holdings, LLC Present Use: The Teapot Dome Oilfield (9,481 acres) area is an active oilfield, producing both oil and gas from more than 500 wells. At the time of transfer out of federal ownership (January 2015), oil production was less than 500 barrels per day. Surviving structures and infrastructure associated with the original oilfield development (1922 to 1924) are ruins and are no longer in use. Significance: The Teapot Dome Oilfield is the popular name for the 9,481-acre Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3 (NPR-3), significant for its 1922–24 engineering development by private producers on federal land, leading to a government scandal of national proportions. -

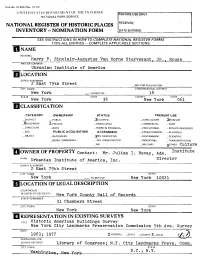

Hclassifi Cation

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STAThS DEPARTMENT OKI HE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE IN STRUCT IONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Harry P. Sinclair-Augustus Van Home Stuyvesant, Jr., House AND/OR COMMON Ukranian Institute of America LOCATION STREET& NUMBER «_ *_•«.« w i > v/ii i^w*vxvxw —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT New York _. VICINITY OF 18 CODE COUNTY CODE New York New York 061 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC — OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE Jfr/IUSEUM -JfeuiLDING(S) X_PR|VATE —UNOCCUPIED — COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS -JfES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY jyOTHER CultUl A (OWNER OF PROPERTY contact: Mr. Julian I. Revay, Adm. Institute NAME Urkanian Institute of America, Inc. Director STREET & NUMBER 2 East 79th Street CITY. TOWN STATE New York VICINITY OF New York 10021 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC New York County Hall of Records STREEF& NUMBER 31 Chambers Street CITY. TOWN STATE New York New York REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS F1TLE Historic American Buildings Survey New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission 5th Ave. Survey DATE 1963; 1977 X-FEDERAL _STATE COUNTY X-LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress; N.Y. City Landmarks Prevs. Comm. CITY. TOWN STATE Washington, New York B.C.; N.Y. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED JfcjNALTERED _J£)RIGINAL SITE vQOOD __RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR __UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE From 1918 to 1930, during the height of both his economic power and his period of disgrace, Harry F. -

Oil & Gas Refining

PDHonline Course M557 (8 PDH) _______________________________________________________________________________ Oil & Gas Refining Production and Processes Instructor: Jurandir Primo, PE 2015 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider www.PDHcenter.com PDHonline Course M557 www.PDHonline.org OIL & GAS REFINING PRODUCTION AND PROCESSES CONTENTS: I. INTRODUCTION II. REFINERIES HISTORY III. TRANSPORTATION HISTORY IV. TRANSPORTATION & STORAGE NOWADAYS V. OIL & GAS REFINING PROCESSES VI. GAS REFINERIES ©2015 Jurandir Primo Page 1 of 87 www.PDHcenter.com PDHonline Course M557 www.PDHonline.org I. INTRODUCTION Refining is a complex series of processes that manufactures finished petroleum products out of cru- de oil. While refining begins as a simple distillation (by heating and separating), refineries use more sophisticated additional processes and equipment in order to produce the mix of products that the market demands. Generally, this latter effort minimizes the production of heavier, lower value pro- ducts (for example, residual fuel oil, used to power large ocean ships) in favor of middle distillates (jet fuel, kerosene, home heating oil and diesel fuel) and lighter, higher value products (liquid petro- leum gases (LPG), naphtha, and gasoline). The main objective of refineries is to convert crude oil into useable petroleum products. Typically, one barrel of crude oil is approximately 19 gallons of gasoline, nine gallons of distillates (home heat- ing fuel, diesel and kerosene), plus lesser amounts of other refined products such as, jet fuel, liquid petroleum gas and residual oil. To a limited extent, refiners can adjust the refining process to alter the resulting mix of refined products, and to fit changing customer needs. -

Renata Condi De Souza.Pdf

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO PUC-SP RENATA CONDI DE SOUZA A REVISTA TIME EM UMA PERSPECTIVA MULTIDIMENSIONAL DOUTORADO EM LINGUÍSTICA APLICADA E ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM SÃO PAULO 2012 2 RENATA CONDI DE SOUZA A REVISTA TIME EM UMA PERSPECTIVA MULTIDIMENSIONAL DOUTORADO EM LINGUÍSTICA APLICADA E ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutora em Linguística Aplicada e Estudos da Linguagem sob orientação do Prof. Dr. Antonio Paulo Berber Sardinha. 3 BANCA EXAMINADORA ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ 4 Aos meus avós, personagens anônimos e não-letrados de imigração, guerras, desemprego e crises econômicas. Personagens da minha história. 5 AGRADECIMENTOS Ao longo de quatro anos de pesquisa, posso dizer que construí uma lista considerável de agradecimentos. Inicio pelo meu orientador, Prof. Dr. Tony Berber Sardinha, sem o qual não teria enveredado pelo caminho da Linguística de Corpus desde o mestrado e cujas qualidades superam aquelas que se espera de um orientador. Agradeço a você, Tony, por acreditar em mim e por me possibilitar acesso a este mundo fantástico da academia e da Linguística de Corpus. Agradeço também ao Grupo de Estudos em Linguística de Corpus (GELC) e a cada um dos seus integrantes. Sem vocês, suas perguntas difíceis e suas soluções fáceis, tão bem-vindas, uma pesquisa de qualidade não seria possível. Obrigada por serem os melhores pares que eu poderia ter tido nestes quatro anos. Agradeço especialmente a Marcia Veirano Pinto e Cristina Mayer Acunzo, amigas queridas, e a Carlos Henrique Kauffmann, pelas contribuições sempre ricas e pela pesquisa de mestrado que tanto esclareceu sobre a Análise Multidimensional. -

Iii.1. National Register Evaluation Criteria

The Development of Highways in Texas: A Historic Context of the Bankhead Highway and Other Historic Named Highways III.1. NATIONAL REGISTER EVALUATION CRITERIA To be eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), a historic-age resource must meet at least one of the four National Register Criteria and retain sufficient integrity to convey its significance. The following discussion defines the significant historical themes and associations set forth in the historic context for the development of highways in Texas and applies them to appropriate National Register Criteria. To possess significance under any of the National Register Criteria as part of this historic context, a resource must be associated with one or more of these themes.1094 In addition, a resource must possess sufficient integrity to convey that significance. The degree to which a resource must retain integrity depends upon the property type and the reasons it is significant under any of the National Register Criteria. The Registration Requirements section of the report provides additional information regarding integrity requirements for each property type. CRITERION A As defined by the National Park Service (NPS), historic resources may be eligible for listing in the National Register under Criterion A if they are “associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history.” For each time period within the context of the development of highways in Texas, the specific events and themes listed below are considered significant. Each theme is significant in its own right; although older themes may be rare, they are not necessarily more significant than recent trends, which often were common but had drastic and wide-ranging impacts upon the built environment. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, APRIL 28, 2016 No. 66 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was Our Democratic friends said— strengthen the hand of the Revolu- called to order by the President pro restoring the regular order promises not tionary Guard, a group that has been tempore (Mr. HATCH). only a more open and transparent process, accused of helping Shiite militias at- but a chance for Senators on both sides of f tack and kill American soldiers in Iraq. the aisle to participate meaningfully in Many of us, including myself, warned PRAYER funding decisions. This is a win-win oppor- that this deal made little sense in tunity and we should seize it together. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- terms of our regional strategy. We That was a letter I received from all fered the following prayer: warned it would enhance Iran’s capa- of our friends on the other side of the Let us pray. bility and its power. Indeed, since sign- aisle. That is exactly what we have ing President Obama’s deal, Iran has Lord, You are in the midst of us and been doing—exactly. The appropria- tested ballistic missiles. It has de- we are called Your children. We confess tions process is off to a strong start, an ployed forces to Syria in support of the that we often fail to live worthy of ‘‘excellent kickoff,’’ in the words of the Assad regime.