Norton in Wartime Was Published

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passion and Glory! Spectacular $Nale to National Series

01 Cover_DC_SKC_V2_APP:Archery 2012 22/9/14 14:25 Page 1 AUTUMN 2014 £4.95 Passion and glory! Spectacular $nale to National Series Fields of victory At home and abroad Fun as future stars shine Medals galore! Longbow G Talent Festival G VI archery 03 Contents_KC_V2_APP:Archery 2012 24/9/14 11:44 Page 3 CONTENTS 3 Welcome to 0 PICTURE: COVER: AUTUMN 2014 £4.95 Larry Godfrey wins National Series gold Dean Alberga Passion and glory! Spectacular $nale to National Series Wow,what a summer! It’s been non-stop.And if the number of stories received over the past few Fields of victory weeks is anything to go by,it looks like it’s been the At home and abroad same for all of us! Because of that, some stories and regular features Fun as future have been held over until the next issue – but don’t stars shine Medals galore! worry,they will be back. Longbow G Talent Festival G VI archery So what do we have in this issue? There is full coverage of the Nottingham Building Society Cover Story National Series Grand Finals at Wollaton Hall, including exclusive interviews with Paralympians John 40 Nottingham Building Society National Series Finals Stubbs and Matt Stutzman.And, as many of our young archers head off to university,we take a look at their options. We have important – and possibly unexpected – news for tournament Features organisers, plus details about Archery GB’s new Nominations Committee. 34 Big Weekend There have been some fantastic results at every level, both at home and abroad.We have full coverage of domestic successes as well the hoard of 38 Field Archery international medals won by our 2eld, para and Performance archers. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

War: How Britain, Germany and the USA Used Jazz As Propaganda in World War II

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Studdert, Will (2014) Music Goes to War: How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/44008/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Music Goes to War How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II Will Studdert Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Kent 2014 Word count (including footnotes): 96,707 255 pages Abstract The thesis will demonstrate that the various uses of jazz music as propaganda in World War II were determined by an evolving relationship between Axis and Allied policies and projects. -

British Aircraft in Russia Bombers and Boats

SPRING 2004 - Volume 51, Number 1 British Aircraft in Russia Viktor Kulikov 4 Bombers and Boats: SB-17 and SB-29 Combat Operations in Korea Forrest L. Marion 16 Were There Strategic Oil Targets in Japan in 1945? Emanuel Horowitz 26 General Bernard A. Schriever: Technological Visionary Jacob Neufeld 36 Touch and Go in Uniforms of the Past JackWaid 44 Book Reviews 48 Fleet Operations in a Mobile War: September 1950 – June 1951 by Joseph H. Alexander Reviewed by William A. Nardo 48 B–24 Liberator by Martin Bowman Reviewed by John S. Chilstrom 48 Bombers over Berlin: The RAF Offensive, November 1943-March 1944 by Alan W. Cooper Reviewed by John S. Chilstrom 48 The Politics of Coercion: Toward A Theory of Coercive Airpower for Post-Cold War Conflict by Lt. Col. Ellwood P. “Skip” Hinman IV Reviewed by William A. Nardo 49 Ending the Vietnam War: A History of America’s Involvement and Extrication from the Vietnam War by Henry Kissinger Reviewed by Lawrence R. Benson 50 The Dynamics of Military Revolution, 1300-2050 by MacGregor Knox and Williamson Murray, eds. Reviewed by James R. FitzSimonds 50 To Reach the High Frontier: A History of U.S. Launch Vehicles by Roger D. Launius and Dennis R. Jenkins, eds. Reviewed by David F. Crosby 51 History of Rocketry and Astronautics: Proceedings of the Thirtieth History Symposium of the International Academy of Astronautics, Beijing, China, 1996 by Hervé Moulin and Donald C. Elder, eds. Reviewed by Rick W. Sturdevant 52 Secret Empire: Eisenhower, the CIA, and the Hidden Story of America’s Space Espionage by Philip Taubman Reviewed by Lawrence R. -

The London Gazette of TUESDAY, the 315* of DECEMBER, 1946 by /Tutyority Registered As a Newspaper

fliimb, 37838 37 FOURTH SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the 315* of DECEMBER, 1946 by /tutyority Registered as a newspaper THURSDAY, 2 JANUARY, 1947 The Air Ministry, January, 1947. AIR OPERATIONS BY THE ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY AIR FORCE IN N.W. EUROPE FROM NOVEMBER 15111, 1943 TO SEPTEMBER SOTH, 1944. The following despatch by the late Air Chief Chief of Staff, I was informed that the Com- Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, K.C.B., bined Chiefs of Staff had appointed me Air D.S.O., Air Commander-in-Chief, Allied 'Oommander-in-Chief of the Allied Expedition- Expeditionary Air Force, was submitted to ary Air Force under yourself as the Supreme the Supreme Allied Commander in November* Allied Commander, and that I was to exercise 1944. operational command of the British and Ameri- can tactical air forces supporting the assault of On relinquishing my command of the Allied Western Europe from the United Kingdom. I Expeditionary Air Force I have the honour to was also informed that a United States General submit the following Despatch, covering its would be appointed Deputy Air Commander-in- operations -under my command during the Chief, Allied Expeditionary Air Force. Major- period from i5th November, 1943 tof 3oth General William 0. Butler was the first General September, 1944. Officer to hold this post. He served in this capa- Since this Despatch covers the air support of city from ist January, 1944, to 25th March, the assault of Europe and the subsequent land 1944, and was succeeded by Major-General operations, it necessarily includes reference to Hoyt S. -

Rollofhonour WWII

TRINITY COLLEGE MCMXXXIX-MCMXLV PRO MURO ERANT NOBIS TAM IN NOCTE QUAM IN DIE They were a wall unto us both by night and day. (1 Samuel 25: 16) Any further details of those commemorated would be gratefully received: please contact [email protected]. Details of those who did not lose their lives in the Second World War, e.g. Simon Birch, are given in italics. Abel-Smith, Robert Eustace Anderson, Ian Francis Armitage, George Edward Born March 24, 1909 at Cadogan Square, Born Feb. 25, 1917, in Wokingham, Berks. Born Nov. 20, 1919, in Lincoln. Son of London SW1, son of Eustace Abel Smith, JP. Son of Lt-Col. Francis Anderson, DSO, MC. George William Armitage. City School, School, Eton. Admitted as Pensioner at School, Eton. Admitted as Pensioner at Lincoln. Admitted as State Scholar at Trinity, Trinity, Oct. 1, 1927. BA 1930. Captain, 3rd Trinity, Oct. 1, 1935. BA 1938. Pilot Officer, Oct. 1, 1938. BA 1941. Lieutenant, Royal Grenadier Guards. Died May 21, 1940. RAF, 53 Squadron. Died April 9, 1941. Armoured Corps, 17th/21st Lancers. Died Buried in Esquelmes War Cemetery, Buried in Wokingham (All Saints) June 10, 1944. Buried in Rome War Hainaut, Belgium. (FWR, CWGC ) Churchyard. (FWR, CWGC ) Cemetery, Italy. (FWR, CWGC ) Ades, Edmund Henry [Edmond] Anderson, John Thomson McKellar Armitage, Stanley Rhodes Born July 24, 1918 in Alexandria, Egypt. ‘Jock’ Anderson was born Jan. 12, 1918, in Born Dec. 16, 1902, in London. Son of Fred- Son of Elie Ades and the Hon. Mrs Rose Hampstead, London; son of John McNicol erick Rhodes Armitage. -

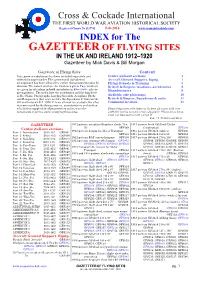

Gazetteer of Flying Sites Index

Cross & Cockade International THE FIRST WORLD WAR AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY Registered Charity No 1117741 Feb.2016 www.crossandcockade.com INDEX for The GAZETTEER OF FLYING SITES IN THE UK AND IRELAND 1912–1920 Gazetteer by Mick Davis & Bill Morgan Gazetteer of Flying Sites Content Data given in tabulations has been included separately and Centre pull-out sections 1 indexed by page number The conventional alphabetical Aircraft Ground Support, Equip. 1 arrangement has been adhered to, rather than presenting sites by Flying Schools & Training 3 function. The names used are the final ones given. Page numbers British & Empire, locations, aerodromes 5 are given for site plans in bold and photos in blue italic, photos Manufacturers 9 given priority. The index lists the aerodromes and the hundreds of Site Plans, Photographs, Landing Grounds, Aeroplane Sheds Airfields, site plan maps 10 and Hangar sites that were used by the Squadrons & Units in the British & Empire, Squadrons & units 11 UK and Ireland 1912–1920. It is an attempt to catalogue the sites Command location 18 that were used by the flying services, manufacturers and civilian schools that supplied the flying services and to trace the Please help correct the index as its been 25 issues with over movements of service units occupying those sites. 3300 line entries so a few errors slipped in Please let us know what you find and we will correct it. Feb. 17, 2016 Derek Riley GAZETTEER 1912 pattern aeroplane/Seaplane sheds, 70 x 1917 pattern brick GS Shed (Under 70' GFS169 Constrution) -

Airpower and the Environment

Airpower and the Environment e Ecological Implications of Modern Air Warfare E J H Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama July 2013 Airpower and the Environment e Ecological Implications of Modern Air Warfare E J H Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama July 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Airpower and the environment : the ecological implications of modern air warfare / edited by Joel Hayward. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58566-223-4 1. Air power—Environmental aspects. 2. Air warfare—Environmental aspects. 3. Air warfare—Case studies. I. Hayward, Joel S. A. UG630.A3845 2012 363.739’2—dc23 2012038356 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. AFRI Air Force Research Institute Air University Press Air Force Research Institute 155 North Twining Street Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6026 http://aupress.au.af.mil ii Contents About the Authors v Introduction: War, Airpower, and the Environment: Some Preliminary Thoughts Joel Hayward ix 1 The mpactI of War on the Environment, Public Health, and Natural Resources 1 Victor W. Sidel 2 “Very Large Secondary Effects”: Environmental Considerations in the Planning of the British Strategic Bombing Offensive against Germany, 1939–1945 9 Toby Thacker 3 The Environmental Impact of the US Army Air Forces’ Production and Training Infrastructure on the Great Plains 25 Christopher M. -

Second World War Roll of Honour

Second World War roll of honour This document lists the names of former Scouts and Scout Leaders who were killed during the Second World War (1939 – 1945). The names have been compiled from official information gathered at and shortly after the War and from information supplied by several Scout historians. We welcome any names which have not been included and, once verified through the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, will add them to the Roll. We are currently working to cross reference this list with other sources to increase its accuracy. Name Date of Death Other Information RAF. Aged 21 years. Killed on active service, 4th February 1941. 10th Barking Sergeant Bernard T. Abbott 4 February 1941 (Congregational) Group. Army. Aged 21 years. Killed on active service in France, 21 May 1940. 24th Corporal Alan William Ablett 21 May 1940 Gravesend (Meopham) Group. RAF. Aged 22 years. Killed on active service, February 1943. 67th North Sergeant Pilot Gerald Abrey February 1943 London Group. South African Air Force. Aged 23 years. Killed on active service in air crash Jan Leendert Achterberg 14 May 1942 14th May, 1942. 1st Bellevue Group, Johannesburg, Transvaal. Flying Officer William Ward RAF. Aged 25 years. Killed on active service 15 March 1940. Munroe College 15 March 1940 Adam Troop, Ontonio, Jamaica. RAF. Aged 23 years. Died on active service 4th June 1940. 71st Croydon Denis Norman Adams 4 June 1940 Group. Pilot Officer George Redvers RAF. Aged 23 years. Presumed killed in action over Hamburg 10th May 1941. 10 May 1940 Newton Adams 8th Ealing Group. New Zealand Expeditionary Force. -

Hangar 4 the Battle of Britain Was One of the Major Turning Points of the Second World War

Large print guide BATTLE OF BRITAIN Hangar 4 The Battle of Britain was one of the major turning points of the Second World War. From the airfield of Duxford to the skies over southern England, follow the course of the battle and discover the stories of the people who were there. Scramble Paul Day 2005 Scramble is a bronze maquette model for part of the Battle of Britain Monument in central London. The monument features many scenes relating to military and civilian life during the Battle of Britain. The centre piece, Scramble, shows pilots running toward their aircraft after receiving orders to intercept an incoming air attack. ZONE 1 Defeat in France May – June 1940 Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, two days after the country invaded Poland. Several months later, on 10 May 1940, Germany attacked Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands and France in a rapid ‘Blitzkrieg’ offensive. During a brief, but costly campaign, Britain deployed multiple Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons to France. The aircraft were sent to support the British Expeditionary Force fighting on the ground and to counter Germany’s powerful air force, the Luftwaffe. Within 6 weeks, France had fallen. The remaining British, French and other Allied troops retreated to the coast, where over half a million were evacuated. The majority departed from the port of Dunkirk. On 22 June, France surrendered to Germany. Britain had lost its main ally and now found itself open to invasion. · 3 September 1939: Britain and France declare war on Germany · 10 May -

Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern

Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern 14 Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern Edited by Mike Bone and David Dawson from contributions by Mike Bone, David Cranstone, David Dawson, David Hunt, Oliver Kent, Mike Ponsford, Andy Pye and Chris Webster Introduction • From c.1540 there was a step-change in the rate of exploitation of our natural resources leading The western aspect of the South West was impor- to radical changes to the landscape. The exploita- tant in earlier times, but during this period it became tion of water for power, transport and later paramount as the strategic interests of Britain devel- the demand for clean drinking water produced oped, first across the Atlantic and then globally. The spectacular changes which apart from individual development of the great naval base at Devonport is monument studies have been largely undocu- an indication of this (Coad 1983). Understanding the mented. Later use of coal-based technology led archaeology of the South West is therefore interde- to the concentration of production and settle- pendent on archaeological work on an international ment in towns/industrial villages. scale and vice versa. The abundance of resources in the region (fuels: coal and natural gas, raw materials • Exploitation for minerals has produced equally for the new age: arsenic, calamine, wolfram, uranium, distinctive landscapes and has remodelled some china clay, ball clay, road stone, as well as traditionally of the “natural” features that are now regarded exploited materials such as copper, tin, lead, agricul- as iconic of the South West, for example, the tural produce and fish) ensured that the region played Avon and Cheddar Gorges, the moorland land- a full part in technological and social changes. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1942

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1942 updated 21/03/07 During the year the chief RCAF Medical Officer in England, W/C A.R. Tilley, moved from London to East Grinstead where his training in reconstructive surgery could be put to effective use (R. Donovan). See July 1944. January 1942 419 Sqn. begins to equip with Wellington Ic aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Air Marshal H. Edwards was posted from Ottawa, where as Air Member for Personnel he had overseen recruitment of instructors and other skilled people during the expansion of the BCATP, to London, England, to supervise the expansion of the RCAF overseas. There he finds that RCAF airmen sent overseas are not being tracked or properly supported by the RAF. At this time the location of some 6,000 RCAF airmen seconded to RAF units are unknown to the RCAF. He immediately takes steps to change this, and eventually had RCAF offices set up in Egypt and India to provide administrative support to RCAF airmen posted to these areas. He also begins pressing for the establishment of truly RCAF squadrons under Article 15 (a program sometimes referred to as "Canadianization"), despite great opposition from the RAF (E. Cable). He succeeded, but at the cost of his health, leading to his early retirement in 1944. Early in the year the Fa 223 helicopter was approved for production. In a program designed by E.A. Bott the results of psychological testing on 5,000 personnel selected for aircrew during 1942 were compared with the results of the actual training to determine which tests were the most useful.