Rajan Kishnan.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

University of Calicut Board of Studies (Ug) In

[Type text] UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT BOARD OF STUDIES (UG) IN JOURNALISM Restructured Curriculum and Syllabi as per CBCSSUG Regulations 2019 (2019 Admission Onwards) PART I B.A. Journalism and Mass Communication PART II Complementary Courses in 1. Journalism, 2. Electronic Media 3. Mass Communication (for BA West Asian Studies) 4. Complementary Courses in Media Practices for B.A LRP Programmes in Visual Communication, Multimedia, and Film and Television for Non-Journalism UG Programmes [Type text] GENERAL SCHEME OF THE PROGRAMME Sl No Course No of Courses Credits 1 Common Courses (English) 6 22 2 Common Courses (Additional Language) 4 16 3 Core Courses 15 61 4 Project (Linked to Core Courses) 1 2 5 Complementary Courses 2 16 6 Open Courses 1 3 Total 120 Audit course 4 16 Extra Credit Course 1 4 Total 140 [Type text] PART I B.A. JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION Distribution of Courses A - Common Courses B - Core Courses C - Complementary Courses D - Open Courses Ability Enhancement Course/Audit Course Extra Credit Activities [Type text] A. Common Courses Sl. No. Code Title Semester 1 A01 Common English Course I I 2 A02 Common English Course II I 3 A03 Common English Course III II 4 A04 Common English Course IV II 5 A05 Common English Course V III 6 A06 Common English Course VI IV 7 A07 Additional language Course I I 8 A08 Additional language Course II II 9 A09 Additional language Course III III 10 A10 Additional language Course IV IV Total Credit 38 [Type text] B. Core Courses Sl. No. Code Title Contact hrs Credit Semester 11 JOU1B01 Fundamentals -

Course : Ba English Language and Literature Open Merit

COURSE : BA ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE OPEN MERIT - SURE LIST Application Index Preference SL.NO Name CATEGORY No. mark No. 1 2108620 FATHIMA MASHAHIL U K 1632 1 MUSLIM 2 2108440 DONA MERCY KURIAN 1625 1 GENERAL 3 2107348 AVANTHIKA MENON 1625 2 GENERAL 4 2106444 NADHA FATHIMA K 1614 1 MUSLIM 5 2111287 DEVIKA S 1612 3 EZHAVA/THIYYA/BILLAVA 6 2104863 FASEEHA MOL A 1611 1 MUSLIM 7 2101654 HIBA MUNEER 1610 1 MUSLIM OBH (OTHER BACKWARD 8 2107980 ABHISHNAV. C V 1610 3 HINDU) 9 2111573 SREENANDA B 1610 1 GENERAL 10 2104436 ARSHA M S 1610 5 GENERAL 11 2100213 ANGEL DOMINIC 1610 1 COMMUNITY 12 2100185 AKHIL SHABU 1610 1 MUSLIM 13 2111615 HANA JABEEN M 1609 2 MUSLIM 14 2111275 AKHILA VINCENT 1608 1 COMMUNITY AMEENA KALAKUDI 15 2110744 1608 1 MUSLIM CHALIL 16 2105938 JASIRA IBRAHIM K 1608 1 MUSLIM OPEN MERIT - WAITING LIST Application Index Preference SL.NO Name CATEGORY No. mark No. 1 2104927 ANNA JIJU 1608 1 GENERAL 2 2105716 RINU ROMY 1607 5 LATIN CATHOLIC (LC) 3 2106684 NIHARIKA S 1606.2 1 GENERAL 4 2105321 ANNADAA RAJESH PADIKKAL 1606 1 GENERAL 5 2101689 NADA THASNEEM 1606 1 MUSLIM 6 2105331 SAHATHA SHERIN C 1605 1 MUSLIM 7 2107935 SWATHI SHINOY 1605 2 EZHAVA/THIYYA/BILLAVA 8 2111647 DIYA RASHEED PANCHILI 1604 3 MUSLIM 9 2103392 NEHA ELIZABETH THOMAS 1603 1 GENERAL 10 2107677 SANTHWANA C S 1602 4 EZHAVA/THIYYA/BILLAVA 11 2107794 PRARTHANA. C 1602 4 EZHAVA/THIYYA/BILLAVA 12 2105246 AMANYA P 1602 1 EZHAVA/THIYYA/BILLAVA 13 2110405 ANNA MEHRI 1601 1 EZHAVA/THIYYA/BILLAVA OPEN MERIT - WAITING LIST OBH (OTHER BACKWARD 14 2110695 DEVIKA S PRAKASH -

Kuttanad Report.Pdf

Measures to Mitigate Agrarian Distress in Alappuzha and Kuttanad Wetland Ecosystem A Study Report by M. S. SWAMINATHAN RESEARCH FOUNDATION 2007 M. S. SWAMINATHAN RESEARCH FOUNDATION FOREWORD Every calamity presents opportunities for progress provided we learn appropriate lessons from the calamity and apply effective remedies to prevent its recurrence. The Alappuzha district along with Kuttanad region has been chosen by the Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India for special consideration in view of the prevailing agrarian distress. In spite of its natural wealth, the district has a high proportion of population living in poverty. The M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation was invited by the Union Ministry of Agriculture to go into the economic and ecological problems of the Alappuzha district as well as the Kuttanad Wetland Ecosystem as a whole. The present report is the result of the study undertaken in response to the request of the Union Ministry of Agriculture. The study team was headed by Dr. S. Bala Ravi, Advisor of MSSRF with Drs. Sudha Nair, Anil Kumar and Ms. Deepa Varma as members. The Team was supported by a panel of eminent technical advisors. Recognising that the process of preparation of such reports is as important as the product, the MSSRF team held wide ranging consultations with all concerned with the economy, ecological security and livelihood security of Kuttanad wetlands. Information on the consultations held and visits made are given in the report. The report contains a malady-remedy analysis of the problems and potential solutions. The greatest challenge in dealing with multidimensional problems in our country is our inability to generate the necessary synergy and convergence among the numerous government, non-government, civil society and other agencies involved in the implementation of the programmes such as those outlined in this report. -

U.O.No. 5868/2017/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 10.05.2017

File Ref.No.26046/GA - IV - E - SO/2016/Admn UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract Faculty of Commerce and Management studies-Revised Regulations, Scheme and Syllabus of Bachelor of Commerce(BCom) Degree Programme under CUCBCSS UG-with effect from the 2017-18 admission-implemented- orders issued. G & A - IV - E U.O.No. 5868/2017/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 10.05.2017 Read:-1.Item No..1 of the Minutes of the meeting of the Board of Studies in Commerce(UG) held on 02.02.2017. 2.Item No.2 of the Minutes of the meeting of the Faculty of Commerce and Management Studies held on 29.03.2017. ORDER As per paper read as (1) above, the meeting of the Board of Studies in Commerce (UG) held on 02.02.2017, resolved to approve and adopt the revised Regulation, Scheme and syllabus of B.Com (CUCBCSS) with effect from the academic year 2017-18. As per paper read as (2) above, the Faculty of Commerce and Management Studies approved the minutes of the Board of Studies in Commerce (UG) read as (1) above. After considering the matter in detail, the Hon'ble Vice Chancellor has accorded sanction to implement the revised Regulation, Scheme and Syllabus of B.Com (CUCBCSS) with effect from 2017-18 admission onwards, subject to ratification by the Academic Council. The following orders are therefore issued; The revised Regulation, Scheme and Syllabus of B.Com (CUCBCSS) is implemented with effect from 2017-18 admission, subject to ratification by the Academic Council. (Revised Regulation, scheme and syllabus appended) Vasudevan .K Assistant Registrar To 1.Principal of all affiliated Colleges offering B.Com programme 2.Controller of Examinations Copy to: PS to VC/PA to PVC/PA to Registrar/PA to CE/J.R, B.Com branch/Digital wing/EX & EG section/SF/DF/FC. -

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Newsletter of Amrita School of Arts and Sciences

NEWS LETTER Vol. 2 May 2017 KOCHI CAMPUS AMRITA SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES, Kochi, gives prime importance to quality teaching, academic research and development and ethical orientation. Dedicated efforts of the teaching community make this a reality. Formal research has been initiated in the areas of Medical Informatics, Data Mining, Applied Art and Media, Commerce and Management. Collaboration with K3A, KMA, and CSI enhance the learning outcome, and extramural Seminars help Dr. U. Krishnakumar Director to develop the calibre of every student. Famous for quality of service, be it in any sector, Amrita Schools have the unique distinction of an excellent support of large task force of Professionals in its mainstream. AMRITAPURI CAMPUS AMRITA SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES, Amritapuri, offers several academics programs at undergraduate, integrated and postgraduate levels. The learning experience in the School is enriched by a team of dedicated teachers guiding the students to get the most in their academic and extra- curricular pursuits. The curriculum provides a flexible credit-based structure and continuous student evaluation to maximize learning and assimilation Dr. V. M. Nandakumaran Principal of fundamental concepts meeting the changing needs of the industry. The School also underpins development of potential to comprehend problems that demand interdisciplinary approach. MYSURU CAMPUS AMRITA SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES, Mysuru, like all schools of Amrita University has adopted a credit based system in keeping with the best traditions of international universities. AMRITA with its best infrastructure, regularly updated curricula and syllabi in line with industry demands, along with gratifying corporate relations assures academic excellence with a global outlook. -

Kerala History Timeline

Kerala History Timeline AD 1805 Death of Pazhassi Raja 52 St. Thomas Mission to Kerala 1809 Kundara Proclamation of Velu Thampi 68 Jews migrated to Kerala. 1809 Velu Thampi commits suicide. 630 Huang Tsang in Kerala. 1812 Kurichiya revolt against the British. 788 Birth of Sankaracharya. 1831 First census taken in Travancore 820 Death of Sankaracharya. 1834 English education started by 825 Beginning of Malayalam Era. Swatithirunal in Travancore. 851 Sulaiman in Kerala. 1847 Rajyasamacharam the first newspaper 1292 Italiyan Traveller Marcopolo reached in Malayalam, published. Kerala. 1855 Birth of Sree Narayana Guru. 1295 Kozhikode city was established 1865 Pandarappatta Proclamation 1342-1347 African traveller Ibanbatuta reached 1891 The first Legislative Assembly in Kerala. Travancore formed. Malayali Memorial 1440 Nicholo Conti in Kerala. 1895-96 Ezhava Memorial 1498 Vascoda Gama reaches Calicut. 1904 Sreemulam Praja Sabha was established. 1504 War of Cranganore (Kodungallor) be- 1920 Gandhiji's first visit to Kerala. tween Cochin and Kozhikode. 1920-21 Malabar Rebellion. 1505 First Portuguese Viceroy De Almeda 1921 First All Kerala Congress Political reached Kochi. Meeting was held at Ottapalam, under 1510 War between the Portuguese and the the leadership of T. Prakasam. Zamorin at Kozhikode. 1924 Vaikom Satyagraha 1573 Printing Press started functioning in 1928 Death of Sree Narayana Guru. Kochi and Vypinkotta. 1930 Salt Satyagraha 1599 Udayamperoor Sunahadhos. 1931 Guruvayur Satyagraha 1616 Captain Keeling reached Kerala. 1932 Nivarthana Agitation 1663 Capture of Kochi by the Dutch. 1934 Split in the congress. Rise of the Leftists 1694 Thalassery Factory established. and Rightists. 1695 Anjengo (Anchu Thengu) Factory 1935 Sri P. Krishna Pillai and Sri. -

VOLVIV January 2015 No. 1 HIGHLIGHTS

VOLVIV January 2015 No. 1 HIGHLIGHTS Censor Board revamped Padma Awards announced 13th Pune International Film Festival held 60th Britannia Filmfare Awards presented Karnataka State Film Awards announced PK tax free in UP and Bihar Birth centenary of Honnappa Bhagavathar celebrated NATIONAL DOCUMENTATION CENTRE ON MASS COMMUNICATION NEW MEDIA WING (FORMERLY RESEARCH, REFERENCE AND TRAINING DIVISION ) MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING Room No.437-442, Phase IV, Soochana Bhavan, CGO Complex, New Delhi-3 Compiled, Edited & Issued by National Documentation Centre on Mass Communication NEW MEDIA WING (Formerly Research, Reference & Training Division) Ministry of Information & Broadcasting Chief Editor L. R. Vishwanath Editor H.M.Sharma Asstt. Editor Alka Mathur CONTENTS FILM AWARDS Bafta 2 Filmfare 4-5 Padma 1-2 State 6-7 FESTIVALS Indian Panorama 2-3 Pune International 3-4 OBITUARIES 8-11 PUBLICATIONS 7 REVIEW/DEVELOPMENT 1 REVIEW/DEVELOPMENT IN STATES 11 TAXATION 7 REVIEW/DEVELOPMENT Censor Board revamped In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of section 3 of the Cinematograph Act 1952 (37 of 1952) read with rule 3 of the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 1983, the Central government has appointed Shri Pahlaj Nihalani as Chairperson of the Central Board of Film Certification in an honorary capacity for a period of three years or until further orders, whichever is earlier. Further, In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of section 3 of the Cinematograph (Certification) Rulers, 1983, the Central government has appointed the following persons as members of the Central Board of Film Certification with immediate effect for a period of three years and until further orders:- Shri Mihir Bhuta, Prof Syed Abdul Bari, Shri Ramesh Patange, Shri George Baker, Dr. -

Synopsis and Other Details

Malayalam Title: Chitrasutram English Title: The Image Threads Malayalam/Color/104 Minutes/India/2010 Produced by Unknown Films with support from Hubert Bals Film Fund, Rotterdam, Goteborg Film Fund, Goteborg, Sweden, and the Global Film Initiative, US. SYNOPSIS A computer teacher, his black-magician grandfather and a cyber-creature -- a series of pre- destined rendezvous, both online and offline, over the shreds of mnemonic time and space, at the cleavages of various parlors of subculture -- finally the narrative images of the computer screen are drained off from the color and the texture, the images collapse down to a mere pulsating pixel, potentially to start another cycle of the story once again. Awards: International Film Festival of Kerala : Hassan Kutty Award for the Best Debut Director. National Film Award 2010 : Best Sound Design. Kerala State Award 2010 : Special Jury Award for the Director. Best Cinematographer. Best Sound Recordist. Padmarajan Puraskaram 2010 : Best Director. Best Script Writer. John Abraham Award 2010 : Special Jury Award for the Director. Film Festival Participated : 1. Rotterdam International Film Festival 2011. (Tiger Awards Competition) 2. International Film Festival of Kerala. 3. Göteborg International Film Festival, 2011 4. São Paulo International Film Festival, 2010 5. South Asian International Film Festival in New York. 6. 10th Asian Film Festival of Dallas- 2011 7. 11th International Film Festival, Wroclaw. Poland- 2011 8. 9th Vladivostok International Film Festival of Asian Pacific countries – “PACIFIC -

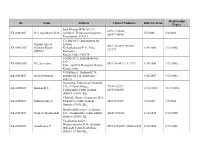

ID Name Address Contact Numbers Effective from Membership Expiry

Membership ID Name Address Contact Numbers Effective from Expiry Jaya Bhavan H No Vi/311, 0471-2290840, KL-0001S07 R.C .Sasidharan Nair Azhikkal, Thiruvananthapuram - 5/5/2008 5/4/2009 08547190840 Trivandrum, 695572 C/o INFACT (Information for Organic Spices Action) 0091 (0) 4822 309281, KL-0002G07 Growers Forum Kizhathadiyoor P.O., Pala, 2/24/2005 2/23/2006 211997 (OFSG) Kottayam Kerala, India -686574 c/o INFACT, Kizhathadiyoor P.O., KL-0003G07 The Secretary 0091 (0) 4822 21 19 97 2/24/2005 2/23/2006 Pala - 686574, Kottayam District Kerala, India Vellukunnel, Thidanad P.O., KL-0004S07 Jacob Sebastian Erattupetta Via, Kottayam, 9/25/2007 9/23/2008 686123 Snehalaya, Payyanchal, Kandoth P.O., Velloor village, 9961616727 / KL-0005S07 Kannan K.V 11/12/2012 11/11/2014 Taliparamba Taluk, Kannur 04985206858 District, 670307 KL Chathoth House, Sivapuram B.O., KL-0006S07 Induchoodan. C Thalassery Taluk, Kannur 04972477507 3/8/2005 3/7/2006 District, 670702 KL Moothedathu house, Arakulam KL-0007S07 Mathew Moothedath S.O., Thodupuzha Taluk, Idukki 04862 252013 5/14/2005 5/13/2006 District, 685591 KL Vararkandy house, Muthuvannacha B.O., Kuttiadi, KL-0008S07 ArunKumar P 0496 2668439, 9846612678 5/14/2005 5/13/2006 Quilandy Taluk, Kozhikode District, 673508 KL Kariyapurayidam, Poonjar Thekkekara S.O., Meenachil KL-0009S07 K.E. Clement 0482 2285129, 9447869685 5/14/2005 5/13/2006 Taluk, Kottayam District, 686582 KL Pananthanathu, Alanad B.O., KL-0010S07 P.D. Mani Meenachil Taluk, Kottayam 0482 2246007 5/14/2005 5/13/2006 District, 'Kareekkunnel', Nariayanganam KL-0011S07 Augustine K. -

Parichya Patra.P65

Student Paper PARICHAY PATRA Spectres of the New Wave : The State of the Work of Mourning, and the New Cinema Aesthetic in a Regional Industry 1 Introduction My title refers to Derrida’s controversial account of his concern with Marx amidst the din and bustle of the ‘end of history’. Time was certainly out of joint and the pluralistic outlook of the great thinker was pitted against the monolith that orthodox communists used to uphold. My primary concern in the paper would be an account of the Malayalam film industry in its post-New Wave phase as well as a handful of filmmakers whose works seem to be difficult to categorize. Within the domain of the popular and amidst the mourning from the film society circle for the movement that lasted no longer than a decade, these films evoke the popular memory of the New Wave. Though up in arms against the worthy ancestors, these filmmakers are unable to conceal their indebtedness to the latter. The New Wave too was not without its heterogeneity, and the “disjointed now” that I am talking about is something “whose border would still be determinable”. I would like to consider the possibility of moving towards translocal contexts without shifting our focus from a specific site of inquiry which, in this case, is Malayalam cinema. The paper will concentrate upon the phenomenon known JOURNAL OF THE MOVING IMAGE 81 as the resurfacing/resurgence of art cinema aesthetics in Indian cinema. Recent scholarly interest in the history of this forgotten film movement is noticeable, more so because it was ignored in the age of disciplinary incarnation of cinematic scholarship in India.