Finding and Funding Voices: the London Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Assembly for Wales Communities

Communities, Equality and Local Government Committee CELG(4)-10-14 Paper 3 National Assembly for Wales Communities, Equality & Local Government Committee Written Evidence March 2014 1 Section 1 1 Introduction 2 Ofcom welcomes this opportunity to submit evidence to the National Assembly for Wales‟ Communities, Equality & Local Government Committee on our activities and regulatory duties. Ofcom is the independent regulator and competition authority for the UK communications industries, with responsibilities across broadcasting, telecommunications, postal services and the airwaves over which wireless devices operate. Ofcom operates under a number of Acts of Parliament and other legislation. These include the Communications Act 2003, the Wireless Telegraphy Act 2006, the Broadcasting Acts 1990 and 1996, the Digital Economy Act 2010 and the Postal Services Act 2011. The Communications Act states that Ofcom‟s general duties should be to further the interests of citizens and of consumers. Meeting these two duties is at the heart of everything we do. As a converged regulator, Ofcom publishes high quality data and evidence about the broadcasting and communications sectors in Wales, through, among others, its annual Communications Market Report, UK Infrastructure Report1 and Public Service Broadcasting Annual Report. The data in much of this submission is based on the latest iterations of these reports, published in 2013. Data for the 2014 reports is currently being collated. The Communications Sector In recent years, consumers in Wales have benefited from significant changes in the way communications services are delivered. As a result, consumer expectations have changed considerably. In the past decade since Ofcom was established, the UK‟s communications market has experienced rapid change: In 2004, most connections to the internet were through a dial up connection and broadband was in its infancy with a maximum speed of 1 or 2 megabits per second. -

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

United Kingdom Distribution Points

United Kingdom Distribution to national, regional and trade media, including national and regional newspapers, radio and television stations, through proprietary and news agency network of The Press Association (PA). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: . Posting to online services and portals with a complimentary ReleaseWatch report. Coverage on PR Newswire for Journalists, PR Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service reaching over 100,000 registered journalists from 140 countries and in 17 different languages. Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Releases are translated and distributed in English via PA. 3,298 Points Country Media Point Media Type United Adones Blogger Kingdom United Airlines Angel Blogger Kingdom United Alien Prequel News Blog Blogger Kingdom United Beauty & Fashion World Blogger Kingdom United BellaBacchante Blogger Kingdom United Blog Me Beautiful Blogger Kingdom United BrandFixion Blogger Kingdom United Car Design News Blogger Kingdom United Corp Websites Blogger Kingdom United Create MILK Blogger Kingdom United Diamond Lounge Blogger Kingdom United Drink Brands.com Blogger Kingdom United English News Blogger Kingdom United ExchangeWire.com Blogger Kingdom United Finacial Times Blogger Kingdom United gabrielleteare.com/blog Blogger Kingdom United girlsngadgets.com Blogger Kingdom United Gizable Blogger Kingdom United http://clashcityrocker.blogg.no Blogger -

Exploring Welsh Speakers' Language Use in Their Daily Lives

Exploring Welsh speakers’ language use in their daily lives Beaufort contacts: Fiona McAllister / Adam Blunt [email protected] [email protected] Bangor University contact: Dr Cynog Prys [email protected] Client contacts: Carys Evans [email protected], Eilir Jones [email protected] Iwan Evans [email protected] July 2013 BBQ01260 CONTENTS 1. Executive summary ...................................................................................... 4 2. The situation, research objectives and research method ......................... 7 2.1 The situation ................................................................................................ 7 2.2 Research aims ......................................................................................... 9 2.3 Research method ..................................................................................... 9 2.4 Comparisons with research undertaken in 2005 and verbatim comments used in the report ............................................ 10 3. Main findings .............................................................................................. 11 4. An overview of Welsh speakers’ current behaviour and attitudes ........ 21 4.1 Levels of fluency in Welsh ...................................................................... 21 4.2 Media consumption and participation in online and general activities in Welsh and English .................................................. 22 4.3 Usage of Welsh in different settings ...................................................... -

Inside … 28....MW Loop Source 2....AM Switch Book

• Serving DX’ers since 933 • Volume 74, No. 23 • March News9, 2007 • (ISSN 0737-659) DX Inside … 28 ...MW Loop Source 2 ...AM Switch Book .. 5 ...Professional Sports Networks 34 ...Musings of the 6 ...DDXD Members 6 ...IDXD 35 ...Boise 2007 25 ...NRC Contest 36 ...Your name Station Test Calendar e-mail reports for members who don’t have com- KMTI UT 650 Mar. 19 0200-0400 puters. Our next DXN: April 2. Happy DX! From the Publisher … Check out page 35 for DXN Publishing Schedule, Volume 74 more information about the unprecedented joint NRC-WTFDA convention in Boise, August 31- Iss. Deadline Pub. Date Iss. Deadline Pub. Date September 2. 24. Mar. 23 Apr. 2 28. July 6 July 6 DXChange … Richard Wood, Ph.D. - HCR 3, 25. Apr. 6 Apr. 6 29. Aug. 3 Aug. 3 Box 11087 - Keaau, HI 96745 is looking for a phas- 26. May. 4 May 4 30. Sept. 7 Sept. 8 ing unit for two or more beverage antennas; must 27. June 8 June 8 work on MW. State asking price. DX Time Machine Unfilled positions… We’re still in need of vol- From the Pages of DX News unteers for the following positions, as described 50 years ago … from the March 16, 1957 DXN: in detail in V73, #27, the June ‘06 DXN: A person Len Kruse, Dubuque, IA, reported that BCB reception proficient with phpBB to maintain the e-DXN site; on Monday am., 2/25 was extremely bad, the worst one or more additional moderators for e-DXN; one he’d had ever remembered for the month of February, or more persons to edit future NRC publications; having heard only WKLM-790 of the 6 NRC DX programs scheduled. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Dogfen I/Ar Gyfer Pwyllgor Diwylliant, Y Gymraeg A

------------------------Pecyn dogfennau cyhoeddus ------------------------ Agenda - Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu Lleoliad: I gael rhagor o wybodaeth cysylltwch a: Ystafell Bwyllgora 2 - y Senedd Steve George Dyddiad: Dydd Iau, 15 Chwefror 2018 Clerc y Pwyllgor Amser: 09.30 0300 200 6565 [email protected] ------ 1 Cyflwyniad, ymddiheuriadau, dirprwyon a datgan buddiannau 2 Amgueddfa Cymru: craffu cyffredinol (09:30 - 10:30) (Tudalennau 1 - 12) David Anderson, Cyfarwyddwr Cyffredinol Neil Wicks, Dirprwy Gyfarwyddwr a Chyfarwyddwr Cyllid ac Adnoddau Corfforaethol Nia Williams, Cyfarwyddwr Addysg ac Ymgysylltu 3 Radio yng Nghymru: Sesiwn dystiolaeth 1: Pwyllgor Cynghori Cymru Ofcom (10:30 - 11:15) (Tudalennau 13 - 32) Glyn Mathias, Cadeirydd y Pwyllgor Hywel Wiliam, Aelod o'r Pwyllgor. 4 Radio yng Nghymru: Sesiwn dystiolaeth 2: Ofcom (11:15 - 12:00) Rhodri Williams, Cyfarwyddwr Cymru Neil Stock, Cyfarwyddwr Trwyddedu Darlledu 5 Papurau i'w nodi 5.1 Ofcom: trafod y Memorandwm Cyd-ddealltwriaeth drafft (12:00 - 12:15) (Tudalennau 33 - 38) 5.2 Cyllid heblaw cyllid cyhoeddus ar gyfer y celfyddydau: Gohebiaeth gan Gyngor Celfyddydau Lloegr (Tudalennau 39 - 43) 6 Cynnig o dan Reol Sefydlog 17.42 i benderfynu gwahardd y cyhoedd o'r cyfarfod ar gyfer y busnes a ganlyn: 7 Trafod y dystiolaeth (12:15 - 12:30) Eitem 2 Mae cyfyngiadau ar y ddogfen hon Tudalen y pecyn 1 AMGUEDDFA CYMRU - Chwefror 2018: Gwybodaeth Gefndirol ar gyfer y Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu Mae 2018 yn flwyddyn o gyfleon i Amgueddfa Cyrmu, wrth i ni ddechrau gweithredu argymhellion yr Adolygiad Thurley, ac ym mis Hydref, cwblhau ailddatblygiad Sain Ffagan: Amgueddfa Werin Cymru. Llwyddiannau yn 2017 Byddwn yn adeiladu ar lwyddiannau a gyflawnwyd yn 2017, a oedd yn cynnwys: Twf yn Niferoedd Ymwelwyr. -

The City and County of Cardiff, County Borough Councils of Bridgend, Caerphilly, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taf and the Vale of Glamorgan

THE CITY AND COUNTY OF CARDIFF, COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCILS OF BRIDGEND, CAERPHILLY, MERTHYR TYDFIL, RHONDDA CYNON TAF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN AGENDA ITEM NO. 4 THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE 14 December 2018 REPORT FOR THE PERIOD 1 September - REPORT OF: 30 November 2018 THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVIST 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT This report describes the work of Glamorgan Archives for the period 1 September to 30 November 2018. 2. BACKGROUND As part of the agreed reporting process the Glamorgan Archivist updates the Joint Committee quarterly on the work and achievements of the service. Members are asked to note the content of this report. 3. ISSUES A. MANAGEMENT OF RESOURCES 1. Staff Maintain establishment Laura Cunningham has been appointed to the role of Archivist on a temporary basis to cover Hannah Price’s maternity leave. Laura has recently qualified and has been volunteering regularly at the Archives while completed the distance-learning course. She joined at the end of November. Adam Latchford and Freya Chambers, Cultural Ambition trainees, began their 6 month placements in September. They have completed an induction period and are assisting in a range of tasks across the service while working on their NVQ Level 2 in Culture and Heritage. Lowis Lovell has returned from maternity leave and is continuing the work of sorting coroner’s papers. The annual staff coffee morning raised £190 for Macmillan Cancer Support. Continue skill sharing volunteer programme During the quarter, 52 volunteers have contributed 1,930 hours to the work of the office. Of these, 30 came from Cardiff, 10 from the Vale of Glamorgan, 6 from Bridgend, 1 from Rhondda Cynon Taf, 1 from Caerphilly, and 4 from outside the area served. -

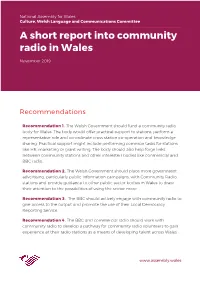

A Short Report Into Community Radio in Wales

National Assembly for Wales Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee A short report into community radio in Wales November 2019 Recommendations Recommendation 1. The Welsh Government should fund a community radio body for Wales. The body would offer practical support to stations, perform a representative role and co-ordinate cross station co-operation and knowledge sharing. Practical support might include performing common tasks for stations like HR, marketing or grant writing. The body should also help forge links between community stations and other interested bodies like commercial and BBC radio. Recommendation 2. The Welsh Government should place more government advertising, particularly public information campaigns, with Community Radio stations and provide guidance to other public sector bodies in Wales to draw their attention to the possibilities of using the sector more. Recommendation 3. The BBC should actively engage with community radio to give access to the output and promote the use of their Local Democracy Reporting Service. Recommendation 4. The BBC and commercial radio should work with community radio to develop a pathway for community radio volunteers to gain experience at their radio stations as a means of developing talent across Wales. www.assembly.wales A short report into community radio in Wales Recommendation 5. The BBC should offer community radio stations preferential rates and first refusal when selling off radio equipment they no longer use. Recommendation 6. Radio Joint Audience Research (RAJAR) should develop a less complex and cheaper audience survey that community radio could use. Stations that chose to use this new service should then be able to access the advertisers that place adverts using RAJAR ratings. -

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / The Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Radio yng Nghymru / Radio in Wales CWLC(5) RADIO01 Ymateb gan Pwyllgor Cynghori Cymru, Ofcom / Evidence from Ofcom Advisory Committee for Wales The possible impact of the deregulation of commercial radio on audiences in Wales In May 2017, the Advisory Committee submitted a response to the consultation by the UK Government Department for Digital Culture Media and Sport (DDCMS) on proposals to deregulate commercial radio within the UK. We supported the broad thrust of the proposed relaxation of current regulatory provision, including the removal of existing music format requirements and Ofcom’s role in ensuring a range of choice in radio services. It is worth explaining why. It is an understandable reaction to suggest that relaxing these requirements will lead to the homogenisation of the radio provision for listeners in Wales. The music will all sound the same and it will be increasingly difficult to tell the stations apart. Surely local commercial stations were meant to be local and reflect the communities they serve instead of becoming (in some cases) just links in a chain of commercial stations across the UK? Commercial radio, however, faces a number of challenges in the coming decade. It already faces competition from the internet, where equivalent stations undergo no regulation of any kind. The potential switchover to digital, whenever it may come, also poses a similar problem. Existing legislation does not provide for any regulatory requirements on digital commercial stations in terms of programme formats or the provision of news. -

CMR WAL Radio

The Communications Market in Wales 3 3 Radio and audio content 79 3.1 Radio and audio content 3.1.1 Recent developments in Wales Community radio Community radio licences are awarded to small-scale operators working on a not-for-profit basis to serve local geographic areas or particular communities. The number of community stations has increased over the past three years, with a total of 228 licence awards since the start of community radio licensing in March 2005. In March 2010, Point FM, serving Rhyl in North Wales, became the latest community radio station to launch, bringing the total number of community stations on the air in Wales to nine, (Figure 3.1). In May, its neighbouring station, Tudno FM in Llandudno, opened a newly refurbished studio at its existing site in the town. In the same month, six community radio stations in Wales received grants totalling £100,000 from the Welsh Assembly Government’s Community Radio Fund. This year’s recipients were: BRFM, Tudno FM, Afan FM, Bro Radio, GTFM and Calon FM. BRFM at the National Eisteddfod, Ebbw Vale. BRFM is a community radio station licensed by Ofcom, based at Brynmawr, near Ebbw Vale at the head of the South Wales valleys. A key feature of the station is coverage of local music, and BRFM also produces video content which is available on YouTube. This year the National Eisteddfod of Wales was held in Ebbw Vale and BRFM obtained a restricted service licence (RSL) from Ofcom to run EVFm which was broadcast from the Eisteddfod field during the week of the festival (31 July to 8 August). -

Media in Wales Serving Public Values

Media in Wales Serving Public Values Geraint Talfan Davies & Nick Morris May 2008 ISBN 978 1 904773 34 4 The Institute of Welsh Affairs is an independent think-tank that promotes quality research and informed debate aimed at making Wales a better nation in which to work and live. We commission research, publish reports and policy papers, and organise events across Wales. We are a membership-based body and a wide range of individuals, businesses and other organisations directly support our activities. Our work embraces a range of topics but especially focuses on politics and the development of the National Assembly for Wales, economic development, education and culture, the environment and health. This research was produced with the support of a Welsh Assembly Government grant. Institute of Welsh Affairs 1 – 3 Museum Place Cardiff CF10 3BD T 029 2066 6606 www.iwa.org.uk Media in Wales – Serving Public Values CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Introduction 1 CHAPTER 2 Broadcasting – Mixed Signals 5 CHAPTER 3 Broadcasting – Television 10 CHAPTER 4 Broadcasting – Radio 24 CHAPTER 5 Wales in Print 33 CHAPTER 6 Wales Online 47 CHAPTER 7 Journalism in Wales 51 CHAPTER 8 What the Audience Thinks 54 CHAPTER 9 Reflections 57 iii Media in Wales – Serving Public Values 1. Introduction extensive poverty both urban and rural, the prevalence of the small scale in broadcast and print media markets, external media ownership, and a In the past decade technological developments new democratic institution – more than justify a have wrought more change in our media closer look at how Wales is served by the media. -

Máire Messenger Davies

A1 The Children’s Media Foundation The Children’s Media Foundation P.O. Box 56614 London W13 0XS [email protected] First published 2013 ©Lynn Whitaker for editorial material and selection © Individual authors and contributors for their contributions. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of The Children’s Media Foundation, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover. ISBN 978-0-9575518-0-0 Paperback ISBN 978-0-9575518-1-7 E-Book Book design by Craig Taylor Cover illustration by Nick Mackie Opposite page illustration by Matthias Hoegg for Beakus The publisher wishes to acknowledge financial grant from The Writers’ Guild of Great Britain. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Editorial Lynn Whitaker 5 2 The Children’s Media Foundation Greg Childs 10 3 The Children’s Media Foundation: Year One Anna Home 14 INDUSTRY NEWS AND VIEWS 4 BBC Children’s Joe Godwin 19 5 Children’s Content on S4C Sioned Wyn Roberts 29 6 Turner Kids’ Entertainment Michael Carrington 35 7 Turner: A View from the Business End Peter Flamman 42 8 Kindle Entertainment Melanie Stokes 45 9 MA in Children’s Digital Media Production, University of Salford Beth Hewitt 52 10 Ukie: UK Interactive Entertainment Jo Twist 57 POLICY, REGULATION AND DEBATE 11 Representation and Rights: The Use of Children