T.H. Stone Memorial St. Joseph Peninsula State Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Problems on Tristan Da Cunha Byj

28 Oryx Conservation Problems on Tristan da Cunha ByJ. H. Flint The author spent two years, 1963-65, as schoolmaster on Tristan da Cunha, during which he spent four weeks on Nightingale Island. On the main island he found that bird stocks were being depleted and the islanders taking too many eggs and young; on Nightingale, however, where there are over two million pairs of great shearwaters, the harvest of these birds could be greater. Inaccessible Island, which like Nightingale, is without cats, dogs or rats, should be declared a wildlife sanctuary. Tl^HEN the first permanent settlers came to Tristan da Cunha in " the early years of the nineteenth century they found an island rich in bird and sea mammal life. "The mountains are covered with Albatross Mellahs Petrels Seahens, etc.," wrote Jonathan Lambert in 1811, and Midshipman Greene, who stayed on the island in 1816, recorded in his diary "Sea Elephants herding together in immense numbers." Today the picture is greatly changed. A century and a half of human habitation has drastically reduced the larger, edible species, and the accidental introduction of rats from a shipwreck in 1882 accelerated the birds' decline on the main island. Wood-cutting, grazing by domestic stock and, more recently, fumes from the volcano have destroyed much of the natural vegetation near the settlement, and two bird subspecies, a bunting and a flightless moorhen, have become extinct on the main island. Curiously, one is liable to see more birds on the day of arrival than in several weeks ashore. When I first saw Tristan from the decks of M.V. -

Red-Footed Booby Helper at Great Frigatebird Nests

264 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS NECTS MEANS ECTS MEANS ICATE SAMPLE SIZE S.D. SAMPLE SIZE 70 IN DAYS FIGURE 2. Culmen length against age of Brown FIGURE 1. Weight against age of Brown Noddy Noddy chicks on Manana Island, Hawaii in 1972. chicks on Manana Island, Hawaii in 1972. about the thirty-fifth day; apparently Brown Noddies on Christmas Island grow more rapidly than those on 5.26 g/day (SD = 1.18 g/day), and chick growth rate Manana. More data are required for a refined analysis and fledging age were negatively correlated (r = of intraspecific variation in growth rates of Brown -0.490, N = 19, P < 0.05). Noddy young. Seventeen of the chicks were weighed both at the This paper is based upon my doctoral dissertation age of fledging and from 3 to 12 days later; there was submitted to the University of Hawaii. I thank An- no significant recession in weight after fledging (t = drew J. Berger for guidance and criticism. The 1.17, P > 0.2), as suggested for certain terns (e.g., Hawaii State Division of Fish and Game kindly LeCroy and LeCroy 1974, Bird-Banding 45:326). granted me permission to work on Manana. This Dorward and Ashmole (1963, Ibis 103b: 447) mea- study was supported by the Department of Zoology sured growth in weight and culmen length of Brown of the University of Hawaii, by an NSF Graduate Noddies on Ascension Island in the Atlantic; scatter Fellowship, and by a Mount Holyoke College Faculty diagrams of their data indicate growth functions very Grant. -

The Effects of Urban and Economic Development on Coastal Zone Management

sustainability Article The Effects of Urban and Economic Development on Coastal Zone Management Davide Pasquali 1,* and Alessandro Marucci 2 1 Environmental and Maritime Hydraulic Laboratory (LIAM), Department of Civil, Construction-Architectural and Environmental Engineering (DICEAA), University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy 2 Department of Civil, Construction-Architectural and Environmental Engineering (DICEAA), University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The land transformation process in the last decades produced the urbanization growth in flat and coastal areas all over the world. The combination of natural phenomena and human pressure is likely one of the main factors that enhance coastal dynamics. These factors lead to an increase in coastal risk (considered as the product of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability) also in view of future climate change scenarios. Although each of these factors has been intensively studied separately, a comprehensive analysis of the mutual relationship of these elements is an open task. Therefore, this work aims to assess the possible mutual interaction of land transformation and coastal management zones, studying the possible impact on local coastal communities. The idea is to merge the techniques coming from urban planning with data and methodology coming from the coastal engineering within the frame of a holistic approach. The main idea is to relate urban and land changes to coastal management. Then, the study aims to identify if stakeholders’ pressure motivated the Citation: Pasquali, D.; Marucci, A. deployment of rigid structures instead of shoreline variations related to energetic and sedimentary The Effects of Urban and Economic Development on Coastal Zone balances. -

Breeding Biology of the Brown Noddy on Tern Island, Hawaii

Wilson Bull., 108(2), 1996, pp. 317-334 BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE BROWN NODDY ON TERN ISLAND, HAWAII JENNIFER L. MEGYESI’ AND CURTICE R. GRIFFINS ABSTRACT.-we observed Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus pileatus) breeding phenology and population trends on Tern Island, French Frigate Shoals, Hawaii, from 1982 to 1992. Peaks of laying ranged from the first week in January to the first week in November; however, most laying occurred between March and September each year. Incubation length was 34.8 days (N = 19, SD = 0.6, range = 29-37 days). There were no differences in breeding pairs between the measurements of the first egg laid and successive eggs laid within a season. The proportion of light- and dark-colored chicks was 26% and 74%, respectively (N = 221) and differed from other Brown Noddy colonies studied in Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The length of time between clutches depended on whether the previous outcome was a failed clutch or a successfully fledged chick. Hatching, fledging, and reproductive success were significantly different between years. The subspecies (A. s. pihtus) differs in many aspects of its breeding biology from other colonies in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, in regard to year-round occurrence at the colony, frequent renesting attempts, large egg size, proportion of light and dark colored chicks, and low reproductive success caused by in- clement weather and predation by Great Frigatebirds (Fregata minor). Received 31 Mar., 1995, accepted 5 Dec. 1995. The Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus) is the largest and most widely distributed of the tropical and subtropical tern species (Cramp 1985). -

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

SALTWATER INTRUSION and CLIMATE CHANGE a Primer for Local and Provincial Decision-Makers

SALTWATER INTRUSION and CLIMATE CHANGE A primer for local and provincial decision-makers. Atlantic Climate Adaptation Solutions Association Saltwater Intrusion and Climate Change 1 SALTWATER INTRUSION and CLIMATE CHANGE Report Prepared by: Prince Edward Island Department of Environment, Labour and Justice Report Edited by: Doug Linzey, Fundy Communications, 2340 Gospel Rd, Canning NS Content Review and Project Management: Prince Edward Island Department of Environment, Labour and Justice, 11 Kent Street, Charlottetown, PE, C1A 7N8, [email protected] Disclaimer: This document was prepared for a specific purpose and should not be applied or relied upon for alternative uses without the permission, advice, and guidance of the authors, the provincial managers, and ACASA, or their respective designates. Users of this report do so at their own risk. Neither ACASA, the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, nor the authors of this report accept responsibility for damages suffered by any third party as a result of decisions or actions taken based on this report. Avertissement: Ce document a été préparé dans un but précis et ne devrait pas être appliqué ou invoqué pour d’autres utilisations sans autorisation, des conseils et des auteurs, les directeurs provinciaux et ACASA, ou leurs représentants respectifs. Les utilisateurs de ce rapport font à leurs risques et périls. Ni ACASA, les provinces de la Nouvelle-Écosse, au Nouveau-Brunswick, Île du Prince Édouard, Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador ou les auteurs de ce rapport acceptent la responsabilité pour les dommages subis par un tiers à la suite de décisions ou actions prises sur la base de ce rapport. -

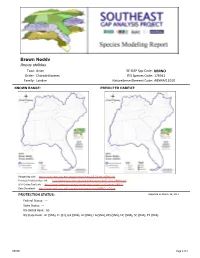

Brown Noddy Anous Stolidus Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Bbrno Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176941 Family: Laridae Natureserve Element Code: ABNNM11010

Brown Noddy Anous stolidus Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bBRNO Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176941 Family: Laridae NatureServe Element Code: ABNNM11010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bBRNO.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bBRNO.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bBRNO Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bBRNO_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: --- NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), FL (S1), GA (SNA), HI (SNR), LA (SNA), MS (SNA), NC (SNA), SC (SNA), TX (SNA) bBRNO Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 US Dept. of Energy US Nat. Park Service NOAA Other Federal Lands ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Native Am. -

Breeding Colonies Distribution of Brown Noddy Lineage

To view this as a map and many more go to: www.nabis.govt.nz web mapping tool Type the map name into: Search for a map layer or place Lineage – Scientific methodology Breeding distribution of Brown noddy lineage 1. A “breeding colony” for New Zealand seabirds is defined as “any location where breeding has been reported and is considered by the expert compiling the species account to have occurred at that location at least until 1998”. 2. An “occasional breeding colony” for New Zealand seabirds is defined as “any location where breeding has been reported, but not necessarily continuously nor during consecutive breeding seasons, and is considered by the expert compiling the species account to have occurred at that location during the last 30 years”. 3. Literature sources were searched for breeding distribution information. a. Scientific papers, published texts, unpublished reports and university theses available to the expert who prepared the distributional layers. b. Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts for 1960-2009. c. OSNZ News and Southern Bird for 1977–2009. 4. Other sources. a. Nil. 5. The mapping of the Brown noddy breeding colony at Curtis Island is based on a written description of its location in Veitch et al. (2004) during 1989, those of the breeding colonies at Lord Howe Island and Norfolk Island are based on written descriptions of their locations in Higgins & Davies (1996), and that of the unknown breeding colony at L’Esperance Rock is based on a written description of its location in Greene et al. (2004) during 2002. The colonies have not been surveyed for mapping purposes, and the mapping presented is based on the written descriptions of their locations. -

Observations of Pelagic Seabirds Wintering at Sea in the Southeastern Caribbean William L

Pp. 104-110 in Studies in Trinidad and Tobago Ornithology Honouring Richard ffrench (F. E. Hayes and S. A. Temple, Eds.). Dept. Life Sci., Univ. West Indies, St. Augustine, Occ. Pap. 11, 2000 OBSERVATIONS OF PELAGIC SEABIRDS WINTERING AT SEA IN THE SOUTHEASTERN CARIBBEAN WILLIAM L. MURPHY, 8265 Glengarry Court, Indianapolis, IN 46236, USA ABSTRACT.-I report observations, including several the educational cruise ship Yorktown Clipper between significant distributional records, of 16 species of Curaçao and the Orinoco River, traversing seabirds wintering at sea in the southeastern Caribbean approximately 2,000 km per trip (Table 1). Because during cruises from Bonaire to the Orinoco River (5-13 the focus was on visiting islands as well as on cruising, January 1996, 3-12 March 1997, and 23 December many of the longer passages were traversed at night. 1997 - 1 January 1998). A few scattered shearwaters While at sea during the day, fellow birders and I (Calonectris diomedea and Puffinus lherminieri) were maintained a sea watch, recording sightings of bird seen. Storm-Petrels (Oceanites oceanicus and species and their numbers. Oceanodroma leucorhoa), particularly the latter species, were often seen toward the east. Most The observers were all experienced birders with tropicbirds (Phaethon aethereus) and gulls (Larus binoculars, some of which were image-stabilised. The atricilla) were near Tobago. Boobies were common; number of observers at any given time ranged from Sula leucogaster outnumbered S. sula by about 4:1 and one to 15, averaging about five. Observations were S. dactylatra was scarce. Frigatebirds (Fregata made from various points on three decks ranging from magnificens) were strictly coastal. -

Coastal Management

Coastal Management Mapping of littoral cells J M Motyka Dr A H Brampton Report SR 326 January 1993 HR Wallingfprd Registered Office: HR Wallingford Ltd. Howbery Park, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OXlO 8BA. UK Telephone: 0491 35381 International+ 44 491 35381 Telex: 848552. HRSWAL G. Facsimile; 0491 32233 lnternationaJ+ 44 491 32233 Registered in England No. 1622174 SR 328 29101193 ---····---- ---- Contract This report describes work commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food under Contract CSA 2167 for which the MAFF nominated Project Officer was Mr B D Richardson. It is published on behalf of the Ministry of Agricutture, Fisheries and Food but any opinions expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the funding Ministry. The HR job number was CBS 0012. The work was carried out by and the report written by Mr J M Motyka and Dr A H Bramplon. Dr A H Bramplon was the Project Manager. Prepared by c;,ljl>.�.�············ . t'..�.0.. �.r.......... (name) Oob title) Approved by ........................['yd;;"(lj:�(! ..... // l7lt.i�w; Dale . .............. f)...........if?J .. © Copyright Ministry of Agricuhure, Fisheries and Food 1993 SA 328 29ro t/93 Summary Coastal Management Mapping of littoral cells J M Motyka Dr A H Brampton Report SR 328 January 1993 As a guide for coastal managers a study has been carried out identifying the major regional littoral drift cells in England and Wales. For coastal defence management the regional cells have been further subdivided into sub-cells which are either independent or only weakly dependent upon each other. The coastal regime within each cell has been described and this together with the maps of the coastline identify the special characteristics of each area. -

SEAFARBIIS«^I.OG Doeombor B

Vol. XX Doeombor B No. 2B SEAFARBIIS«^I.OG 19St » OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THI SEAFARERS INTERNATIONAL UNION • ATLANTIC AND GULF DISTRICT • AFL-CIO • I't ~' ''•/.'X '"ll j ' J '* "i ' i'^J.Z fmt ' ' i' l- «• «"••• k . « • f. V Hfl .. i t." • €>EATTLe \ • Joint Picket Action r' , Affects 160 Vessels NEW YORK, Dee. 4—Jolnriy led by tho SiUNA and NMU, the American union - ?: •.. protest on the runaways produced the following results as of 10 PM (EST) tonlghtt b 160 runaway ships affected in 20 poets. b Only 23 ships escaped from behind picketiines. Most of them left with little or no cargo handled, and i/dthout tugs or pilots. 4. " b Injunctions halted picketing on only six ships, b No American-flag ship lost time due to picketing in any port. —Complete Details on Page 3 . ?'y^' - • •••• •' l' • - • : --.-f/;". ^ Ci i,'ji Misi® :li:;.'•/•••; •/.Kl »it [EMS toe •^1 i '•,•• i'!.. V • • • • 'Go To NLRBV Court EXCERPTS FkOIN JUDGE'S RUUNC Says; OK's ITF Beef {Ed. not*'. The following are tom* direct gtiotei .from Judge Bryan'* decision in u^ich he refused to glM tunawcty shipowners Hopes entertained by American owners of runaway tonnage that the US an injunction against demonstrations hy But American maritims courts would block united labor demonstrations against them< were deflated by unions.) ^ the decision isisued by Federal Judge Frederick van Pelt Bryan, lit addi^n to » » » refusing to issue an in-^ front when the National Labor Re ing that any fraud or violence has f'The Taft-Hartley Act ... doies not authorize any per junction against the SIU lations Board ruled that the run been CT will be resorted to lo as son aggrieved by unfair labor piractices to bring suit in and the National Maritime away ship SS Florida was actually to bring the case within those sec the courts .. -

SWAP 2015 Report

STATE WILDLIFE ACTION PLAN September 2015 GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES WILDLIFE RESOURCES DIVISION Georgia State Wildlife Action Plan 2015 Recommended reference: Georgia Department of Natural Resources. 2015. Georgia State Wildlife Action Plan. Social Circle, GA: Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Recommended reference for appendices: Author, A.A., & Author, B.B. Year. Title of Appendix. In Georgia State Wildlife Action Plan (pages of appendix). Social Circle, GA: Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Cover photo credit & description: Photo by Shan Cammack, Georgia Department of Natural Resources Interagency Burn Team in Action! Growing season burn on May 7, 2015 at The Nature Conservancy’s Broxton Rocks Preserve. Zach Wood of The Orianne Society conducting ignition. i Table&of&Contents& Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ iv! Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ x! I. Introduction and Purpose ................................................................................................. 1! A Plan to Protect Georgia’s Biological Diversity ....................................................... 1! Essential Elements of a State Wildlife Action Plan .................................................... 2! Species of Greatest Conservation Need ...................................................................... 3! Scales of Biological Diversity