Ikioda, Faith.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Registered Hospitality and Tourism Enterprises As At

REGISTERED HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM ENTERPRISES AS AT MARCH, 2020 NATURE OF S/N NAME OF ESTABLISHMENTS ADDRESS/LOCATION BUSINESS 1 TOURIST COMPANY OF NIG(FEDERAL PALACE HOTEL 6-8, AHMADU BELLO STREET, LAGOS HOTEL PLOT, 1415 ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA ST. V/I 2 EKO HOTELS & SUITES LAGOS HOTEL 3 SHERATON HOTEL 30, MOBOLAJI BANK ANTHONY WAY IKEJA. HOTEL 4 SOUTHERN SUN IKOYI HOTEL 47, ALFRED REWANE RD, IKOYI LAGOS HOTEL 5 GOLDEN TULIP HOTEL AMUWO ODOFIN MILE 2 HOTEL 6 LAGOS ORIENTAL HOTEL 3, LEKKI ROAD, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS HOTEL 1A, OZUMBA MBADIWE STREE, VICTORIA 7 RADISSON BLU ANCHORAGE HOTEL ISLAND, LAGOS HOTEL 8 FOUR POINT BY SHERATON PLOT 9&10, ONIRU ESTATE, LEKKI HOTEL 9 MOORHOUSE SOFITEL IKOYI 1, BANKOLE OKI STREET, IKOYI HOTEL MILAND INDUSTRIES LIMITED (INTERCONTINETAL 10 HOTEL) 52, KOFO ABAYOMI STR, V.I HOTEL CBC TOWERS, 8TH FLOOR PLOT 1684, SANUSI 11 PROTEA HOTEL SELECT IKEJA FAFUNWA STR, VI HOTEL 12 THE AVENUE SUITES 1390, TIAMIYU SAVAGE VICTORIA ISLAND HOTEL PLOT, 1415 ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA ST. V/I 13 EKO HOTELS & SUITES (KURAMO) LAGOS HOTEL PLOT, 1415 ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA ST. V/I 14 EKO HOTELS & SUITES (SIGNATURE) LAGOS HOTEL 15 RADISSON BLU (FORMERLY PROTEA HOTEL, IKEJA) 42/44, ISAAC JOHN STREET, G.R.A, IKEJA HOTEL 16 WHEATBAKER HOTEL (DESIGN TRADE COMPANY) 4, ONITOLO STREET, IKOYI - LAGOS HOTEL 17 PROTEA (VOILET YOUGH)PARK INN BY RADISSON VOILET YOUGH CLOSE HOTEL 18 BEST WESTERN CLASSIC ISLAND PLOT1228, AHAMDADU BELLO WAY, V/I HOTEL 19 LAGOS AIRPORT HOTEL 111, OBAFEMI AWOLOWO WAY, IKEJA HOTEL 20 EXCELLENCE HOTEL & CONFERENCE CENTRE IJAIYE OGBA RD., OGBA, LAGOS HOTEL 21 DELFAY GUEST HOUSE 3, DELE FAYEMI STREET IGBO ELERIN G H 22 LOLA SPORTS LODGE 8, AWONAIKE CRESCENT, SURULERE G H 23 AB LUXURY GUEST HOUSE 20, AKINSOJI ST. -

C, Feg 19 2009

OMB No 1545-0047 dorm 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax 2007 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public 3rtment of the Treasury naI Revenue Service(71 The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Ins pection A For the 2007 calendar year, or tax y ear be g innin g Jul 1 , 2007 , and endin Jun 30 , 2008 B Check if applicable C Name of organization D Employer Identification Number Please use Address change IRS label Pathfinder International 53-0235320 or p not Name change or type Number and street (or P 0 box if marl is not delivered to street addr) Room/suite E Telephone number See Initial return specific 9 Galen Street 217 (617) 924-7200 Instruc- Accounting City , town or county State ZIP code + 4 F Cash Accrual Termination lions. y method IL(i Amended return Watertown MA 02472-4501 Other(specfy)0" Application pending • Section 501(c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt H and l are not applicable to section 527 organizations charitable trusts must attach a completed Schedule A H (a) Is this a group return for affiliates' q Yes No (Form 990 or 990-EZ). H (b) it 'Yes,' enter number of affiliates G Web Site:', www . p athfind.or g H (c) Are all affiliates included? q Yes q No ( if 'No,' attach a list See instructions ) J Organization type (check onl y one ) 501(c) 3 4 (insert no ) q 4947( a)(1) or 11 527 H (d) Is this a separate return tiled by an organization ruting7 K Check here If the organization is not a 509(a)(3) supporting organization and its covered by a group Yes FX] gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 A return is not required, but if the I Grou p Exem p tion Number 0. -

World Bank Document

Lagos State Ministry of Commercial Agriculture The World Bank, NIGERIA Agriculture & Cooperatives Development Project Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Public Disclosure Authorized For the Commercial Agriculture Development Projects at the ARAGA FARM SETTLEMENT, Poka, Epe, Lagos State (Final Report) APRIL 2013 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... 8 LIST OF PLATES ........................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................... 10 LIST OF ACRONYMS .............................................................................................................. 12 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 14 CHAPTER ONE ....................................................................................................................... 181 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................... 18 1.0 Background ................................................................................................................................. 18 1.1 Tasks of the Consultant ............................................................................................................ -

Organizational Effectiveness in Higher Education: a Case Study of Selected Polytechnics in Nigeria

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SCIENCES SOUTHAMPTON EDUCATION SCHOOL Organizational Effectiveness in Higher Education: A Case Study of Selected Polytechnics in Nigeria by Oluwole Adeniyi Solanke Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy APRIL 2014 1 ABSTRACT This study compares perceived organisational effectiveness within polytechnic higher education in Nigeria. A qualitative methodology and an exploratory case study (Yin, 2003) enable an in-depth understanding of the term effectiveness as it affects polytechnic education in Nigeria. A comparative theoretical framework is applied, examining three polytechnic institutions representing Federal, State and Private structures under a variety of conditions. Data was based on triangulation comprising fifty-two (52) semi-structured interviews, one focus group, and documentary evidence. The participants in the study were the dominant coalition in the institutions comprising top- academic leaders, lecturers, non-academic staff, and students. -

CLEAN TECHNOLOGY FUND Lagos Cable Car Project USD 20 Million

CLEAN TECHNOLOGY FUND Lagos Cable Car Project USD 20 million March 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 6 3. CTF INVESTMENT CRITERIA 11 4. MONITORING & EVALUATION 13 5. CONCLUSIONS 13 ANNEX I: CTF INVESTMENT CRITERIA CALCULATIONS 14 ANNEX II: RISKS AND MITIGANTS 15 ANNEX III: PROJECT AREA 17 2 Cover Page for CTF Project/Program Approval Request Dedicated Private Sector Programs (DPSP-III) 2. CIF Project 1. Country/Region Nigeria [CIF AU will ID# assign ID] Public 3. Public or Private Private X 4. Project/Program Title Lagos Cable Car Project 5. Is this a private sector program Yes composed of sub-projects? No X 6. Financial Products, Terms and Amounts USD EUR Financial Product (million) (million) Grant 0.00 Fee on grant 0.00 MPIS (for private sector only) 0.00 Public sector loan Harder terms 0.00 Softer terms 0.00 Senior loan 20.00 Senior loans in local currency hedged 0.00 Subordinated debt / mezzanine instruments with income 0.00 Secondparticipation loss guarantees 0.00 Equity 0.00 Subordinated debt/mezzanine instruments with convertible 0.00 Convertiblefeatures grants and contingent recovery grants 0.00 Contingent recovery loans 0.00 First loss guarantees 0.00 Other (please specify) 0.00 Total 7. Implementing MDB(s) AfDB 8. National Implementing Agency NA 9. MDB Focal Point Leandro Azevedo ([email protected]) 10. Brief Description of Project/Program (including objectives and expected outcomes)[c] The project entails the development, construction and operation of the first phase/green line of the Lagos Cable Car Transit (LCCT) project, an aerial cable car public transport system that comprises 4 stations and spans 4.67 km connecting Lagos island to Victoria island. -

Local Institutions, Fetish Oaths and Blind Loyalties to Political Godfathers in South-Western Nigeria

Local Institutions, Fetish Oaths and Blind Loyalties to Political Godfathers in South-Western Nigeria Olusegun Afuape, Lagos State Polytechnic, Lagos, Nigeria The IAFOR North American Conference on the Social Sciences Official Conference Proceedings 2014 Abstract This paper examines the involvement of traditional rulers and other institutions such as Community Development Association (CDA) and Community Development Council (CDC) in the mobilization for both local and General Elections in south- western Nigeria. It argues that the upgrading of some village heads to the position of kings, together with the creation of the position where it was hitherto non-existent, as well as secret but fetish oaths of loyalty sworn to by political sons/daughters to guarantee their loyalty, is deliberately done with a view to using them as a veritable tool to mobilize for grassroots support during General Elections. Using interview and observation, the conceptual framework for this study is David Easton's system analysis and this is augmented with the theory of violence as espoused by Hannah Arendt and Jenny Pearce. The problems created by the politicization of these institutions are blind loyalty of traditional leaders, politicians and members of community associations to the political Godfathers, deification of these Godfathers, imposition of unpopular and incompetent candidates in political offices, misappropriation of public funds and all manner of corruption, among others. Hence, the required remedies to these factors are proffered after which this paper concludes that for violence to disappear, there is the need for political gladiators and electorate to desist and resist the politicization of local institutions and the installation of literate and non-violent candidates as either a village head or a king. -

OYEWO, ISHOLA SAHEED Address: 33A, Beecroft Street, Lagos Island, Lagos

OYEWO, ISHOLA SAHEED Address: 33a, Beecroft Street, Lagos Island, Lagos. E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 07033904681, 08054522184 OBJECTIVE To work in an organization with or without supervision in order to contribute my quota to the overall achievement of organizational goal while also adding value to myself PERSONAL ATTRIBUTES Self-motivated and result oriented Excellent communication and good interpersonal skill A dedicated team player, flexible, adaptable and able to face new challenge with enthusiasm. Ability to Learn Fast WORK EXPERIENCE BusinessDay Media Ltd Business Development Executive BusinessDay Training Responsibilities July 2014- May 2015 Preparation of annual training calendar Marketing training programmes to clients Preparation of training advertisement in the newspaper and online Research into training needs of clients Planning and organizing trainings and workshops Managing the social media platforms, website information. Preparation of management report BusinessDay Media Limited. Feb- July 2014 Head, Youth Segment/Campus Sales Responsibilities Engagement of stakeholders in all tertiary institutions Monitoring, co-ordination, and supervision of all campus sales’ executive nationwide Securing regular subscription for the newspaper Initiating/organizing students’ oriented programmes/projects Collation of reports for weekly management meeting Guaranty Trust Bank Plc, International Airport Road, Lagos 2012-2014 Transaction Officer Responsibilities Customer Relationship Identifying New Market for -

INTRODUCTION Lagos State with Population of Over 10 Million

Ife Journal of Science vol. 14, no. 1 (2012) 75 INTEGRATED GEOPHYSICAL AND GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATION OF A BRIDGE SITE - A CASE STUDY OF A SWAMP/CREEK ENVIRONMENT IN SOUTH EAST LAGOS, NIGERIA Salami, B. M.*, Falebita, D. E.*, Fatoba, J.O**, and Ajala, M.O*** * Department of Geology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria ** Department of Earth Science, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago- Iwoye, Nigeria *** Row-Dot Ltd, Lagos Corresponding Author: [email protected] (Received: 4th Nov., 2011; Accepted: 23rd May, 2012) ABSTRACT Integrated geophysical and geotechnical investigation was carried out at a bridge site within a creek and swamp environment in parts of Agbowa, South East Lagos. This was with a view to delineating the subsoil sequence and determining the engineering properties. The investigation involved three shell and auger boring and seven Vertical Electrical Soundings (VES) using the Schlumberger electrode array. Analysis of results of the boring lithological logs indicates occurrence of four major layers composed of clay, organic clay, silty sandy clay and sandy deposits to about 40 m depth. Results of the in-situ and laboratory tests reveal that the silty-sandy soils are characterized by low N-values that range from 5 to 15, while the clayey soils are characterized by high void ratio of 1.73 and low Cu values of 22 kN/m20 with 4 indicating the poor strength and highly compressible nature of the subsoil sequence. The electrical resistivity survey results show good correlation with boring logs and further indicated occurrence of a highly resistive (>1000 ohm-m) basal sandy deposit beyond the boring probe to appreciable depth of over 80 m. -

Spatial Variations of Values of Residential Land Use in Lagos Metropolis (Pp

An International Multi-Disciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 3 (2), January, 2009 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) Spatial Variations of Values of Residential Land Use in Lagos Metropolis (Pp. 381-403) Leke Oduwaye -Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos. [email protected] ; [email protected] Abstract The cost of land has very strong influence on the quality and type of development that can be sustained on such land. Residential areas are no exception. This is more pronounced in economically vibrant. Lagos being the economic nerve centre of Nigeria fall into this category cities. This study is therefore to further enrich existing literature in this area but focusing on residential land values in Metropolitan Lagos. In the study, the actual prices of various components of residential land use are established which the study classified into rent, purchase price of residential apartments and purchase price of residential plots of land. This was done for different residential land use types which the study classified into three: namely high density, medium density and low density areas. The study concludes that residential land values are high in the low density areas and lower at the high density areas. The paper suggests the need to improve both physical and economic access to residential properties, privatization of the supply of infrastructural facilities, improvement in the quality of the environment and the need to release lands under public ownership to make more land available for residential use. Keywords: Residential, Land Value, Neighbourhood, Rent, Cost, Land. Copyright: IAARR, 2009 www.afrrevjo.com 381 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info African Research Review Vol. -

Urban Planning Processes in Lagos

URBAN PLANNING PROCESSES IN LAGOS Policies, Laws, Planning Instruments, Strategies and Actors of Urban Projects, Urban Development, and Urban Services in Africa’s Largest City Second, Revised Edition 2018 URBAN PLANNING PROCESSES IN LAGOS Policies, Laws, Planning Instruments, Strategies and Actors of Urban Projects, Urban Development, and Urban Services in Africa’s Largest City Second, Revised Edition 2018 URBAN PLANNING PROCESSES IN LAGOS Policies, Laws, Planning Instruments, Strategies and Actors of Urban Projects, Urban Development, and Urban Services in Africa’s Largest City Second, Revised Edition 2018 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/de/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Jointly published by: Heinrich Böll Stiftung Nigeria FABULOUS URBAN 3rd Floor, Rukayyat Plaza c/o Vulkanplatz 7 93, Obafemi Awolowo Way 8048 Zürich Opposite Jabi Motor Park Switzerland Jabi District, Abuja, Nigeria [email protected] [email protected] www.ng.boell.org www.fabulousurban.com Editorial supervision: Monika Umunna Editor and lead researcher: Fabienne Hoelzel Local researchers and authors: Kofo Adeleke, Olusola Adeoye , Ebere Akwuebu, Soji Apampa, Aro Ismaila, Taibat Lawan- son, Toyin Oshaniwa, Lookman Oshodi, Tao Salau, Temilade Sesan, and Olamide Udoma-Ejorh, Field research: Solabomi Alabi, Olugbenga Asaolu, Kayode Ashamu, Lisa Dautel, Antonia -

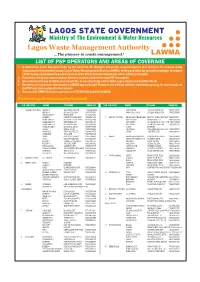

List of Psp Operators and Areas of Coverage 1

LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT Ministry of The Environment & Water Resources Lagos Waste Management Authority ...The pioneer in waste management! LAWMA LIST OF PSP OPERATORS AND AREAS OF COVERAGE 1. In furtherance of the Executive Order by the Governor, Mr. Babajide Sanwo-Olu, on government's zero tolerance for reckless waste disposal and environmental abuse, Lagos Waste Management Authority (LAWMA), hereby publishes for general knowledge, the names of PSP operators mandated to provide services in the 20 Local Government Areas and 37 LCDAs in the state. 2. Remember to bag your wastes and put them in covered containers for easy PSP evacuation. 3. Also endeavour to pay promptly your waste bills, as we collectively work to make Lagos cleaner and healthier for all. 4. Residents are enjoined to download the LAWMA app on Google Playstore and visit our website, www.lawma.gov.ng, for more details on the PSP operators assigned to their streets. 5. You can call LAWMA for back up services on 07080601020 and 08034242660. #ForAGreaterLagos #KeepLagosClean #PayYourWastebill S/N LGA/LCDA WARDS PSP NAME PHONE NO S/N LGA/LCDA WARDS PSP NAME PHONE NO 1 AGBADO OKE ODO ABORU I GOFERMC NIG LTD "08038498764 OMITUNTUN IYALAJE WASTE CO. "08073171697 ABORU II MOJAK GOLD ENT "08037163824 SANTOS/ILUPEJU GOLDEN RISEN SUN "08052323909 ABULE EGBA II FUMAB ENT "08164147462 AGBADO CHRISTOCLEAR VENT "08058461400 7 AMUWO ODOFIN ABULE ADO/TRADE FAIR NEXT TO GODLINESS ENT "08033079011 AGBELEKALE I ULTIMATE STEVE VENT "08185827493 ADO FESTAC DOMOK NIG LTD "08053939988 AGBELEKALE II KHARZIBAB ENT "08037056184 EKO AKETE OLUWASEUN INV. COY LTD "08037139327 AGBELEKALE III METROPOLITAN "08153000880 IFELODUN GLORIOUS RISE ENT "08055263195 AGBULE EGBA I WOTLEE & SONS "08087718998 ILADO RIVERINE AJASA BOIISE TRUST "08023306676 IREPODUN CARLYDINE INV.