Rare Plant Monitoring Program Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTICLE X. LANDSCAPING Sec 8-447. Purpose. the City of Del Rio

ARTICLE X. LANDSCAPING Sec 8-447. Purpose. The City of Del Rio experiences frequent droughts and is in a semi-arid climatic zone; therefore, it is the purpose of this article to: (1) Encourage the use of drought resistant plants and landscaping techniques that do not consume large quantities of water. Plants native to Southern Texas/Coahuila Desert are recommended. (2) Establish requirements for the installation and maintenance of landscaping on developed commercial properties in order to improve, protect, and preserve the appearance, character and value of such properties and their surrounding neighborhoods and thereby promote the public health, safety and general welfare of the citizens of Del Rio. More specifically, it is the purpose of this article to: (a) Aid in stabilizing the environment's ecological balance by contributing to the process of air purification, oxygen regeneration, storm water runoff retardation and groundwater recharge; (b) Reduce soil erosion by slowing storm water runoff; (c) Aid in the abatement of noise, glare and heat; (d) Aid in energy conservation; (e) Provide visual buffering and provide contrast and relief from the built-up environment; and (f) Protect and enhance property value and public and private investment and enhance the beautification of the city. (3) Contribute to and enhance the economic welfare of the city and the quality of life of citizens and visitors through the following: a. Promote the image of the southwestern border environment; and b. Create an attractive appearance along city streets -

Types of American Grasses

z LIBRARY OF Si AS-HITCHCOCK AND AGNES'CHASE 4: SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM oL TiiC. CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE United States National Herbarium Volume XII, Part 3 TXE&3 OF AMERICAN GRASSES . / A STUDY OF THE AMERICAN SPECIES OF GRASSES DESCRIBED BY LINNAEUS, GRONOVIUS, SLOANE, SWARTZ, AND MICHAUX By A. S. HITCHCOCK z rit erV ^-C?^ 1 " WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1908 BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Issued June 18, 1908 ii PREFACE The accompanying paper, by Prof. A. S. Hitchcock, Systematic Agrostologist of the United States Department of Agriculture, u entitled Types of American grasses: a study of the American species of grasses described by Linnaeus, Gronovius, Sloane, Swartz, and Michaux," is an important contribution to our knowledge of American grasses. It is regarded as of fundamental importance in the critical sys- tematic investigation of any group of plants that the identity of the species described by earlier authors be determined with certainty. Often this identification can be made only by examining the type specimen, the original description being inconclusive. Under the American code of botanical nomenclature, which has been followed by the author of this paper, "the nomenclatorial t}rpe of a species or subspecies is the specimen to which the describer originally applied the name in publication." The procedure indicated by the American code, namely, to appeal to the type specimen when the original description is insufficient to identify the species, has been much misunderstood by European botanists. It has been taken to mean, in the case of the Linnsean herbarium, for example, that a specimen in that herbarium bearing the same name as a species described by Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum must be taken as the type of that species regardless of all other considerations. -

AMERICAN 0/ AŒDICUNAL 'Ö^ PLANTS of COMMERCIAL Importajsfce

AMERICAN 0/ AŒDICUNAL 'Ö^ PLANTS OF COMMERCIAL IMPORTAJSfCE i>i :<ic MISCELLANEOUS .,,„ PUBLICATION No.77 ^'' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AMONG THE WILD PLANTS of the United States are many £\ that have long been used m the practice of medicine, some only locally and to a minor extent, but others in sufficient quantity to make them commercially important. The collection of such plants for the crude-drug market provides a livelihood for many people in rural communities, especially in those regions where the native flora has not been disturbed by agricultural or industrial expansion and urban development. There is an active interest in the collection of medicinal i)lants because it appeals to many people as an easy means of making money. However, it frequently requires hard work, and the returns, on the whole, are very moderate. Of the many plants reported to possess medicinal properties, relatively few are marketable, and some of these are required only in small quantities. Persons without previous experience in collecting medicinal plants should first ascertain which of the marketable plants are to be found in their own locality and then learn to recognize them. Before undertaking the collection of large quantities, samples of the bark, root, herb, or other available material should be submitted to reliable dealers in crude drugs to ascertain the market requirements at the time and the prevailing prices. To persons without botanical training it is difficult to describe plants in sufficient detail to make identification possible unless such descriptions are accompanied by illustrations. It is the purpose of this publication to assist those interested in collecting medicinal plants to identify such plants and to furnish other useful information in connection with the work. -

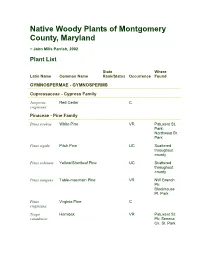

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland ~ John Mills Parrish, 2002 Plant List State Where Latin Name Common Name Rank/Status Occurrence Found GYMNOSPERMAE - GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae - Cypress Family Juniperus Red Cedar C virginiana Pinaceae - Pine Family Pinus strobus White Pine VR Patuxent St. Park; Northwest Br. Park Pinus rigida Pitch Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus echinata Yellow/Shortleaf Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus pungens Table-mountain Pine VR NW Branch Pk; Blockhouse Pt. Park Pinus Virginia Pine C virginiana Tsuga Hemlock VR Patuxent St. canadensis Pk; Seneca Ck. St. Park ANGIOSPERMAE - MONOCOTS Smilacaceae - Catbrier Family Smilax glauca Glaucous Greenbrier C Smilax hispida Bristly Greenbrier UC/R Potomac (syn. S. River & Rock tamnoides) Ck. floodplain Smilax Common Greenbrier C rotundifolia ANGIOSPERMAE - DICOTS Salicaceae - Willow Family Salix nigra Black Willow C Salix Carolina Willow S3 R Potomac caroliniana River floodplain Salix interior Sandbar Willow S1/E VR/X? Plummer's & (syn. S. exigua) High Is. (1902) (S.I.) Salix humilis Prairie Willow R Travilah Serpentine Barrens Salix sericea Silky Willow UC Little Bennett Pk.; NW Br. Pk. (Layhill) Populus Big-tooth Aspen UC Scattered grandidentata across county - (uplands) Populus Cottonwood FC deltoides Myricaceae - Bayberry Family Myrica cerifera Southern Bayberry VR Little Paint Branch n. of Fairland Park Comptonia Sweet Fern VR/X? Lewisdale, peregrina (pers. com. C. Bergmann) Juglandaceae - Walnut Family Juglans cinerea Butternut S2S3 R -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Bulletin Number / Numéro 2 Entomological Society of Canada Société D’Entomologie Du Canada June / Juin 2008

Volume 40 Bulletin Number / numéro 2 Entomological Society of Canada Société d’entomologie du Canada June / juin 2008 Published quarterly by the Entomological Society of Canada Publication trimestrielle par la Société d’entomologie du Canada ............................................................... .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. .......................................................................... ........................................................................................................................................................................ ....................... ................................................................................. ................................................. List of contents / Table des matières Volume 40 (2), June / june 2008 Up front / Avant-propos ................................................................................................................49 Moth balls / Boules à mites .............................................................................................................51 Meeting announcements / Réunions futures ..................................................................................52 Dear Buggy / Cher Bibitte ..............................................................................................................53 -

Illustrated Flora of East Texas Illustrated Flora of East Texas

ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS IS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF: MAJOR BENEFACTORS: DAVID GIBSON AND WILL CRENSHAW DISCOVERY FUND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, USDA FOREST SERVICE) TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT SCOTT AND STUART GENTLING BENEFACTORS: NEW DOROTHEA L. LEONHARDT FOUNDATION (ANDREA C. HARKINS) TEMPLE-INLAND FOUNDATION SUMMERLEE FOUNDATION AMON G. CARTER FOUNDATION ROBERT J. O’KENNON PEG & BEN KEITH DORA & GORDON SYLVESTER DAVID & SUE NIVENS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY OF TEXAS DAVID & MARGARET BAMBERGER GORDON MAY & KAREN WILLIAMSON JACOB & TERESE HERSHEY FOUNDATION INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT: AUSTIN COLLEGE BOTANICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TEXAS SID RICHARDSON CAREER DEVELOPMENT FUND OF AUSTIN COLLEGE II OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: ALLDREDGE, LINDA & JACK HOLLEMAN, W.B. PETRUS, ELAINE J. BATTERBAE, SUSAN ROBERTS HOLT, JEAN & DUNCAN PRITCHETT, MARY H. BECK, NELL HUBER, MARY MAUD PRICE, DIANE BECKELMAN, SARA HUDSON, JIM & YONIE PRUESS, WARREN W. BENDER, LYNNE HULTMARK, GORDON & SARAH ROACH, ELIZABETH M. & ALLEN BIBB, NATHAN & BETTIE HUSTON, MELIA ROEBUCK, RICK & VICKI BOSWORTH, TONY JACOBS, BONNIE & LOUIS ROGNLIE, GLORIA & ERIC BOTTONE, LAURA BURKS JAMES, ROI & DEANNA ROUSH, LUCY BROWN, LARRY E. JEFFORDS, RUSSELL M. ROWE, BRIAN BRUSER, III, MR. & MRS. HENRY JOHN, SUE & PHIL ROZELL, JIMMY BURT, HELEN W. JONES, MARY LOU SANDLIN, MIKE CAMPBELL, KATHERINE & CHARLES KAHLE, GAIL SANDLIN, MR. & MRS. WILLIAM CARR, WILLIAM R. KARGES, JOANN SATTERWHITE, BEN CLARY, KAREN KEITH, ELIZABETH & ERIC SCHOENFELD, CARL COCHRAN, JOYCE LANEY, ELEANOR W. SCHULTZE, BETTY DAHLBERG, WALTER G. LAUGHLIN, DR. JAMES E. SCHULZE, PETER & HELEN DALLAS CHAPTER-NPSOT LECHE, BEVERLY SENNHAUSER, KELLY S. DAMEWOOD, LOGAN & ELEANOR LEWIS, PATRICIA SERLING, STEVEN DAMUTH, STEVEN LIGGIO, JOE SHANNON, LEILA HOUSEMAN DAVIS, ELLEN D. -

Plant Identification Presentation

Today’s Agenda ◦ History of Plant Taxonomy ◦ Plant Classification ◦ Scientific Names ◦ Leaf and Flower Characteristics ◦ Dichotomous Keys Plant Identification Heather Stoven What do you gain Looking at plants more closely from identifying plants? Why is it ◦ How do plants relate to each other? How are they important? grouped? • Common disease and insect problems • Cultural requirements • Plant habit • Propagation methods • Use for food and medicine Plant Classification Plant Classification Group each plant into a specific category Group each plant into a specific category Maple Spiraea Viburnum Crabapple Maple Spiraea Apple tree Ash Viburnum Crabapple Daylily Geranium Apple tree Ash Tomato Poinsettia Daylily Geranium TREES Oak Pepper Tomato Poinsettia Weeping willow Mint Oak Pepper Petunia Euonymus Weeping willow Mint Petunia Euonymus OS-Plant ID.ppt, page 1 Plant Classification Plant Classification Group each plant into a specific category Group each plant into a specific category Maple Spiraea Maple Spiraea Viburnum Crabapple Viburnum Crabapple Apple tree Ash Ornamental Apple tree Ash Edible Daylily Geranium Flowering Daylily Geranium Tomato Poinsettia Plants Tomato Poinsettia Crops Oak Pepper Oak Pepper Weeping willow Mint Weeping willow Mint Petunia Euonymus Petunia Euonymus Carolus Linnaeus Plant Taxonomy The Father of Taxonomy ◦ Identifying, classifying and assigning ◦ Swedish botanist scientific names to plants ◦ Developed binomial ◦ Historical botanists trace the start of nomenclature taxonomy to one of Aristotle’s students, Theophrastus (372-287 B.C.), but he didn’t ◦ Cataloged plants based on create a scientific system natural relationships—primarily flower structures (male and ◦ He relied on the common groupings of female sexual organs) folklore combined with growth: tree, shrub, undershrub or herb ◦ Published Species Naturae in ◦ Detected the process of germination and 1735 and Species Plantarum in realized the importance of climate and soil 1753 to plants ◦ Then, along came Linnaeus…. -

Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of the Washington - Baltimore Area

Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of the Washington - Baltimore Area Part II Monocotyledons Stanwyn G. Shetler Sylvia Stone Orli Botany Section, Department of Systematic Biology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0166 MAP OF THE CHECKLIST AREA Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of the Washington - Baltimore Area Part II Monocotyledons by Stanwyn G. Shetler and Sylvia Stone Orli Department of Systematic Biology Botany Section National Museum of Natural History 2002 Botany Section, Department of Systematic Biology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0166 Cover illustration of Canada or nodding wild rye (Elymus canadensis L.) from Manual of the Grasses of the United States by A. S. Hitchcock, revised by Agnes Chase (1951). iii PREFACE The first part of our Annotated Checklist, covering the 2001 species of Ferns, Fern Allies, Gymnosperms, and Dicotyledons native or naturalized in the Washington-Baltimore Area, was published in March 2000. Part II covers the Monocotyledons and completes the preliminary edition of the Checklist, which we hope will prove useful not only in itself but also as a first step toward a new manual for the identification of the Area’s flora. Such a manual is needed to replace the long- outdated and out-of-print Flora of the District of Columbia and Vicinity of Hitchcock and Standley, published in 1919. In the preparation of this part, as with Part I, Shetler has been responsible for the taxonomy and nomenclature and Orli for the database. As with the first part, we are distributing this second part in preliminary form, so that it can be used, criticized, and updated while the two parts are being readied for publication as a single volume. -

Calcareous Fens in Southeast Alaska

United States Department of Agriculture Calcareous Fens in Southeast Forest Service Pacifi c Northwest Alaska Research Station 1 Research Note Michael H. McClellan, Terry Brock, and James F. Baichtal PNW-RN-536 February 2003 Abstract Calcareous fens have not been identifi ed previously in southeast Alaska. A limited survey in southeast Alaska identifi ed several wetlands that appear to be calcare- ous fens. These sites were located in low-elevation discharge zones that are below recharge zones in carbonate highlands and talus foot-slopes. Two of six surveyed sites partly met the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources water chemistry criteria for calcareous fens, with pH values of 6.7 to 7.4 and calcium concentrations of 41.8 to 51.4 mg/L but fall short with regard to specifi c conductivity (315 to 380 μS/cm). Alkalinity was not determined. The vegetation was predominately herbaceous, with abundant Sitka sedge (Carex aquatilis) and scattered shrubs such as Barclay’s willow (Salix barclayi) and redosier dogwood (Cornus sericea ssp. sericea). The taxa found in these fens have been reported at other sites in southeast Alaska, although many were at the southern limits of their known ranges. The soils were Histosols composed of 0.6 to greater than 1 m of sedge peat. We found no evidence of calcium carbonate precipitates (marl or tufa) in the soil. Keywords: Alaska (southeast), fens, calcareous fens, wetlands, peatlands, karst. Introduction Calcareous fens, a subtype of extremely rich fen, are important because of their rarity, their distinctive water chemistry, and because they frequently harbor rare or endangered plants (Calcareous Fen Technical Committee 1994). -

Crooked-Stem Aster,Symphyotrichum Prenanthoides

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Crooked-stem Aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2012 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2012. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Crooked-stem Aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 33 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the crooked-stem aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 16 pp. Zhang, J.J., D.E. Stephenson, J.C. Semple and M.J. Oldham. 1999. COSEWIC status report on the crooked-stem aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the crooked-stem aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-16 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Allan G. Harris and Robert F. Foster for writing the status report on the Crooked-stem Aster, Symphyotrichum prenanthoides, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Jeannette Whitton and Erich Haber, Co- chairs of the COSEWIC Vascular Plants Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur L’aster fausse-prenanthe (Symphyotrichum prenanthoides) au Canada. -

New York Natural Heritage Program Rare Plant Status List May 2004 Edited By

New York Natural Heritage Program Rare Plant Status List May 2004 Edited by: Stephen M. Young and Troy W. Weldy This list is also published at the website: www.nynhp.org For more information, suggestions or comments about this list, please contact: Stephen M. Young, Program Botanist New York Natural Heritage Program 625 Broadway, 5th Floor Albany, NY 12233-4757 518-402-8951 Fax 518-402-8925 E-mail: [email protected] To report sightings of rare species, contact our office or fill out and mail us the Natural Heritage reporting form provided at the end of this publication. The New York Natural Heritage Program is a partnership with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and by The Nature Conservancy. Major support comes from the NYS Biodiversity Research Institute, the Environmental Protection Fund, and Return a Gift to Wildlife. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... Page ii Why is the list published? What does the list contain? How is the information compiled? How does the list change? Why are plants rare? Why protect rare plants? Explanation of categories.................................................................................................................... Page iv Explanation of Heritage ranks and codes............................................................................................ Page iv Global rank State rank Taxon rank Double ranks Explanation of plant