Studies in Salesian Spirituality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson's Poetry

International Academy Journal Web of Scholar ISSN 2518-167X PHILOLOGY THE MOTIVE OF ASCETICISM IN EMILY DICKENSON’S POETRY Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid, Ph.D. Odlar Yurdu University, Baku, Azerbaijan DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 25 November 2019 This paper is an attempt to analyze the poetry of Miss Emily Dickinson Accepted: 12 January 2020 (1830-1886) contributed both American and World literature in order to Published: 31 January 2020 reveal the extent of asceticism in it. Asceticism involves a deep, almost obsessive, concern with such problems as death, the life after death, the KEYWORDS existence of the soul, immortality, the existence of God and heaven, the meaningless of life and etc. Her enthusiastic expressions of life in poems spiritual asceticism, psychological had influenced the development of poetry and became the source of portrait, transcendentalism, Emily inspiration for other poets and poetesses not only in last century but also . Dickenson’s poetry in modern times. The paper clarifies the motives of spiritual asceticism, self-identity in Emily Dickenson’s poetry. Citation: Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. (2020) The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson’s Poetry. International Academy Journal Web of Scholar. 1(43). doi: 10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 Copyright: © 2020 Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. -

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character J. Steven Davis Submitted to Dr. Jerry Sutton School of Divinity Liberty University September 19, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Research Proposal Abstract .............................................................................................................................11 Background ......................................................................................................................11 Limitations ........................................................................................................................18 Method of Research .........................................................................................................19 Thesis Statement ..............................................................................................................21 Outline ...............................................................................................................................21 Bibliography .....................................................................................................................27 Chapter II: Background of Athanasius An Influential Figure .......................................................................................................33 Early Life ..........................................................................................................................33 Arian Conflict ...................................................................................................................36 -

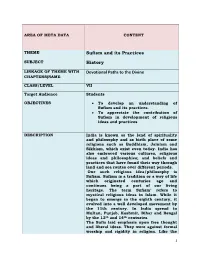

Sufism and Its Practices History Devotional Paths to the Divine

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME Sufism and its Practices SUBJECT History LINKAGE OF THEME WITH Devotional Paths to the Divine CHAPTERS(NAME CLASS/LEVEL VII Target Audience Students OBJECTIVES To develop an understanding of Sufism and its practices. To appreciate the contribution of Sufism in development of religious ideas and practices DESCRIPTION India is known as the land of spirituality and philosophy and as birth place of some religions such as Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, which exist even today. India has also embraced various cultures, religious ideas and philosophies; and beliefs and practices that have found their way through land and sea routes over different periods. One such religious idea/philosophy is Sufism. Sufism is a tradition or a way of life which originated centuries ago and continues being a part of our living heritage. The term Sufism’ refers to mystical religious ideas in Islam. While it began to emerge in the eighth century, it evolved into a well developed movement by the 11th century. In India spread to Multan, Punjab, Kashmir, Bihar and Bengal by the 13th and 14th centuries. The Sufis laid emphasis upon free thought and liberal ideas. They were against formal worship and rigidity in religion. Like the 1 Bhakti saints, the Sufis too interpreted religion as ‘love of god’ and service of humanity. Sufis believe that there is only one God and that all people are the children of God. They also believe that to love one’s fellow men is to love God and that different religions are different ways to reach God. -

Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan

Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan By Zainub Beg A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, K’jipuktuk/Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Theology and Religious Studies. December 2020, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright Zainub Beg, 2020 Approved: Dr. Syed Adnan Hussain Supervisor Approved: Dr. Reem Meshal Examiner Approved: Dr. Sailaja Krishnamurti Reader Date: December 21, 2020 1 Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan by Zainub Beg Abstract Abida Parveen, often referred to as the Queen of Sufi music, is one of the only female qawwals in a male-dominated genre. This thesis will explore her performances for Coke Studio Pakistan through the lens of gender theory. I seek to examine Parveen’s blurring of gender, Sufism’s disruptive nature, and how Coke Studio plays into the two. I think through the categories of Islam, Sufism, Pakistan, and their relationship to each other to lead into my analysis on Parveen’s disruption in each category. I argue that Parveen holds a unique position in Pakistan and Sufism that cannot be explained in binary terms. December 21, 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 3 Chapter One: Introduction .................................................................................. -

A Reformed Asceticism

A Reformed asceticism Jason Radcliff Tito Colliander began his now classic text Way of the Ascetics with this statement: Faith comes not through pondering but through action. Not words and speculation but experience teaches us what God is. To let in fresh air we have to open a window; to get tanned we must go out into the sunshine. Achieving faith is no different; we never reach a goal by just sitting in comfort and waiting, say the holy Fathers. Let the Prodigal Son be our example. He arose and came (Luke 15:20).1 ‘Faith comes not through pondering but through action.’ The concept of ‘asceticism’ is one that is not often discussed within Protestant and Reformed circles. This is likely due, among other things, to views of the life of an ascetic as that of a recluse hidden away in a cave focused on his or her own personal salvation; this is then considered to be a distortion of human life with a confusion concerning salvation and what salvation actually is. No doubt there have been many distortions of what asceticism really is, however the practice itself has held a prominent place in the history of the church, and asceticism properly rooted in the grace of God in Christ should be considered an essential element in the classical tradition of the church. This article will argue that ‘classical asceticism’ is rooted in and flows from the grace of God. This means that asceticism is a response to God’s love for humankind and the incorporation of human beings into the divine life by grace. -

Asceticism and Early Christian Lifestyle

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Faculty of Theology University of Helsinki Finland Joona Salminen Asceticism and Early Christian Lifestyle ACADEMIC DISSERTATION to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Theology at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XIV, University main building, on the 25th of March 2017, at 12 noon. Helsinki 2017 Pre-examiners Doc. Erik Eliasson Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies ThD Patrik Hagman Åbo Akademi University Opponent Doc. Erik Eliasson Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies ISBN 978-951-51-3044-0 (pbk.) ISBN 978-951-51-3045-7 (pdf) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2017 Contents Acknowledgements 5 List of Original Publications 8 Abstract 11 Introduction: Polis, Philosophy, and Perfection 15 1. From City to Desert, and back again The Social Function of Early Christian Asceticism 69 2. From Symposium to Gymnasium Physical and Spiritual Exercises in Early Christianity 95 3. The City of God and the Place of Demons City Life and Demonology in Early Christianity 123 4. Clement of Alexandria on Laughter A Study on an Ascetic Performance in Context 141 5. Clement and Alexandria A Moral Map 157 Bibliography 179 Acknowledgements Seriously, doing full-time academic research is a luxury. The ancient Greeks referred to this kind of luxury by the term scholē, from which the words ‘school’ and ‘scholarship’ derive. Although learning a required dialectic, utilizing complicated sources, and developing convincing argumentation take any candidate to her or his intellectual limits, a scholastēs is a person who ‘lives at ease’ compared to many other hard workers. -

Athanasius of Alexandria and “The Kingdom of the Desert” in His Works

VOX PATRUM 35 (2015) t. 64 Eirini ARTEMI* ATHANASIUS OF ALEXANDRIA AND “THE KINGDOM OF THE DESERT” IN HIS WORKS The concept of monasticism is ancient and can be found in many reli- gions and philosophies. In the centuries immediately before Christ, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism developed alternative styles of life which involved renouncing the world in some ways, in order to seek liberation or purification or union with God, sometimes as a solitary ascetic, sometimes in community. In the third and fourth century, a significant numbers of Christians preferred the desert as the way to come closer to God. So they abandoned their family life and they chose the isolation in the wilderness as the safe path which ends in their deification1. The wilderness in the Bible is a barely perceptible space, an in-between place where ordinary life is suspended, identity shifts, and where the new pos- sibilities emerge. Beginning with the Exodus and then through the Old Testa- ment times, the desert was regarded as a place of spiritual renewal and return to God2. From the experiences of the Israelites in exile, one can learn that the Biblical wilderness is a place of danger, temptation, and chaos, but it is also a place for solitude, nourishment, and revelation from God3. These themes emerge again in Jesus’ journey into the wilderness after His baptism (cf. Mt 4:1-11; Mk 1:12-13; Lk 4:1-13) and when the Christianity started to develop in the period of Roman Empire. Early Christian monasticism drew its inspira- tion from the examples of the Prophet Elijah and John the Baptist, who both lived alone in the desert and above all from the story of Jesus’ time in solitary struggling with Satan in the desert, before his public ministry4. -

Paul and Asceticism in 1 Corinthians 9:27A Kent L

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary Portland Seminary 2008 Paul and Asceticism in 1 Corinthians 9:27a Kent L. Yinger George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Yinger, Kent L., "Paul and Asceticism in 1 Corinthians 9:27a" (2008). Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary. 9. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Portland Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Religion & Society Volume 10 (2008) The Kripke Center ISSN 1522-5658 Paul and Asceticism in 1 Corinthians 9:27a Kent L. Yinger, George Fox Evangelical Seminary Abstract Amidst the resurgence of interest in Paul and asceticism relatively little focus has been put upon one Pauline text with seemingly obvious ascetic potential: “I beat my body” (1 Corinthians 9:27a). After a brief introduction to the discussion of asceticism and an ascetic Paul, this article will survey the Wirkungsgeschichte of this text, especially in the patristic era, engage in exegesis of 1 Corinthians 9:27a, and draw conclusions as to the relevance of the text for discussion of Pauline asceticism. An Ascetic Paul? Recent Discussion [1] Most study of Paul and asceticism focuses on 1 Corinthians 7 and the apostle’s attitude toward sexuality and marriage, comparing it with Hellenistic and Jewish sexual ethics. -

Orthodox Mysticism and Asceticism

Orthodox Mysticism and Asceticism Orthodox Mysticism and Asceticism: Philosophy and Theology in St Gregory Palamas’ Work Edited by Constantinos Athanasopoulos Orthodox Mysticism and Asceticism: Philosophy and Theology in St Gregory Palamas’ Work Edited by Constantinos Athanasopoulos This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Constantinos Athanasopoulos and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5366-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5366-8 CONTENTS Letter from His Eminence Metropolitan of Veroia, Naousa and Campagnia, Mr. Panteleimon ............................................................ vii Introduction ............................................................................................... xi Dr. Constantinos Athanasopoulos Part A. Theology 1. Hesychasm and Theology ....................................................................... 2 Professor Georgios I. Mantzarides (Emeritus at the Faculty of Theology, University of Thessaloniki, Greece) 2. Principles of Biblical Exegesis in the Homilies for Major Feast Days and the Hagiorite Tomos of St Gregory Palamas .................................... -

25. Asceticism and Vocational Awareness

25. Asceticism and Vocational Awareness How do we keep our minds and hearts fastened on the kingdom of God from one day to the next, from month to month and year to year? I think every religious, every priest, every married couple that looks at life in vocational terms, and any Christian called to remain single in the world knows how much attentiveness and effort are required to remain God-centered. The great commandment about loving God with all our mind, heart and strength is realizable, but it is also the project of a lifetime. The discipline necessary in order to lead our lives according to the Great Commandment of Deuteronomy 6:5 is what asceticism is all about. Whenever it becomes linked to mortification asceticism gets a bad name. A healthy Christian spirituality today has to start with a positive assessment of the created world. God fashioned the heavens and the earth and pronounced them “good.” While sin has certainly distorted things, even to the point of rendering some parts of the human world grotesque, it has not canceled the Creator’s primeval blessing. For this reason we dare to live in patient expectation of the new heavens and the new earth envisioned in Isaiah 65:17 and Revelation 21:1—a world in which the power of sin will have been definitively broken. Mortification—the killing of the flesh— sounds strangely at odds with the sentiments of our age precisely because its underlying attitude is one of suspicion toward creation and a chronic nervousness about physicality, bodiliness and sexuality. -

Chapter One: Solitude Versus Community Pages 1 - 20

Kuzyszyn 1 Attractions of Monasticism: A Comparison of Four Late Antique Monastic Rules Table of Contents Chapter One: Solitude Versus Community Pages 1 - 20 Chapter Two: Schools of Art Pages 21 - 40 Chapter Three: Terms of Association Pages 41 - 61 Chapter Four: Benedictine Appeal, Influence, and Legacy Pages 62 - 76 Chapter Five: Conclusion Pages 77 - 83 Adriana Kuzyszyn Kuzyszyn 2 Chapter One Solitude Versus Community Salvation has long been the quest of countless individuals. In the early medieval period, certain followers of western Christianity concerned themselves with living ascetically ideal lives in order to reach redemption. This type of lifestyle included a withdrawal from society. To many, solitude could lead to the eventual obtainment of the ascetic goal. Solitude, however, was not the only requirement for those who desired a spiritual lifestyle. Individuals who longed for purity of heart and Christian reward would only yield results by keeping several other aspects of Christianity in mind, “Key notions…are…the importance of scripture, both as a source of ideas and, through recitation, as a means to tranquility and self-control; the value ascribed to individual freedom…and the awareness of God’s presence as both the context and the focus of work and prayer.”1 Together, a solitary lifestyle and the freedom that accompanies it, the importance of scripture, and the everlasting presence of God came to characterize the existence of those who strove to work towards complete austerity. In this thesis, I hope to explore one fork of the ascetic path – monasticism. Communal monastic living proved to be popular in the late antique and early medieval periods.