25. Asceticism and Vocational Awareness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acquired Contemplation Full

THE ART OF ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION FOR EVERYONE (Into the Mystery of God) Deacon Dr. Bob McDonald ECCE HOMO Behold the Man Behold the Man-God Behold His holy face Creased with sadness and pain. His head shrouded and shredded with thorns The atrocious crown for the King of Kings Scourged and torn with forty lashes Humiliated and mockingly adored. Pleading with love rejected Impaled by my crucifying sins Yet persisting in his love for me I see all this in his tortured eyes. So, grant me the grace to love you As you have loved me That I may lay down my life in joy As you have joyfully laid down your life for me. In the stillness I seek you In the silence I find you In the quiet I listen For the music of God. THE ART OF ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION Chapter 1 What is Acquired Contemplation? Chapter 2 The Christian Tradition Chapter 3 The Scriptural Foundation Chapter 4 The Method Chapter 5 Expectations Chapter 6 The Last Word CHAPTER 1 WHAT IS ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION? It will no doubt come as a surprise For the reader to be told that acquired contemplation is indeed somethinG that can be “acquired” and that it is in Fact available to all Christians in all walKs oF liFe. It is not, as is commonly held, an esoteric practice reserved For men and women oF exceptional holiness. It is now Known to possess a universal potential which all oF us can enjoy and which has been larGely untapped by lay Christians For niGh on 2000 years. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson's Poetry

International Academy Journal Web of Scholar ISSN 2518-167X PHILOLOGY THE MOTIVE OF ASCETICISM IN EMILY DICKENSON’S POETRY Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid, Ph.D. Odlar Yurdu University, Baku, Azerbaijan DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 25 November 2019 This paper is an attempt to analyze the poetry of Miss Emily Dickinson Accepted: 12 January 2020 (1830-1886) contributed both American and World literature in order to Published: 31 January 2020 reveal the extent of asceticism in it. Asceticism involves a deep, almost obsessive, concern with such problems as death, the life after death, the KEYWORDS existence of the soul, immortality, the existence of God and heaven, the meaningless of life and etc. Her enthusiastic expressions of life in poems spiritual asceticism, psychological had influenced the development of poetry and became the source of portrait, transcendentalism, Emily inspiration for other poets and poetesses not only in last century but also . Dickenson’s poetry in modern times. The paper clarifies the motives of spiritual asceticism, self-identity in Emily Dickenson’s poetry. Citation: Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. (2020) The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson’s Poetry. International Academy Journal Web of Scholar. 1(43). doi: 10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 Copyright: © 2020 Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. -

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character J. Steven Davis Submitted to Dr. Jerry Sutton School of Divinity Liberty University September 19, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Research Proposal Abstract .............................................................................................................................11 Background ......................................................................................................................11 Limitations ........................................................................................................................18 Method of Research .........................................................................................................19 Thesis Statement ..............................................................................................................21 Outline ...............................................................................................................................21 Bibliography .....................................................................................................................27 Chapter II: Background of Athanasius An Influential Figure .......................................................................................................33 Early Life ..........................................................................................................................33 Arian Conflict ...................................................................................................................36 -

Transcending the Limits of Finitude in St. Bonaventure's Itinerarium Mentis

Transcending the Limits of Finitude In St. Bonaventure’s Itinerarium Mentis in Deum San Beda College Moses Aaron T. Angeles, Ph.D. he “Itinerarium Mentis in Deum” has been described as Finitude of Limits the Transcending an essentially Franciscan tract, guiding learned men in the spirit of St. Francis to his mode of contemplative life. Though intended by St. Bonaventure as a guide towards meditation and contemplation, it is our intention to emphasize and elaborate on a theme,T particularly on the question of transcendence and human finitude, within the Itinerarium rather than to controvert the prevailing scholarly judgments regarding the nature and utility of ... the work. St. Bonaventure’s description of how man comes to his self-realization or self-identity is simultaneously an inventory of man’s intellectual powers and operations with a collage of Scriptural injunctions regulating the course of intellectual introspection. The coalescence of these two dimensions is an entree to the Truth of God. After the reflection of the mind upon itself, man discovers that he is an imago Dei. The name imago was given by God to man in Genesis. But now, man re-enacts that part of Creation and appropriates the name to himself. The act of self-naming is a cry of attenuated triumph. The power to name is an activity of dominion, and the act of self-nomination is the consummate exhibition of human autonomy. First of all, the term “Transcendence” and “Person”1 is not very appropriate terms when it comes to St. Bonaventure and the Itinerarium. The term “Person” as we understood it now speaks about subjectivity, the self, uniqueness, autonomy, the Existential which is in stark contrast to the Boethian universal definition of person 1 St. -

CONTEMPLATION and the FORMATION of the VIR SPIRITUALIS in BONAVENTURE's COLLATIONES in HEXAEMERON Jay M. Hammond in 1273, From

CONTEMPLATION AND THE FORMATION OF THE VIR SPIRITUALIS IN BONAVENTURE’S COLLATIONES IN HEXAEMERON Jay M. Hammond In 1273, from Easter (April 9) to Pentecost (May 28),1 Bonaventure delivered his Collationes in Hexaemeron at the Franciscan Convent of Cordeliers at the University of Paris.2 They are third in a series of collationes3 he delivered at Paris between 1267–1273 and represent his final synthesis.4 Attacks against the mendicants and the domi- nance of Averroistic Aristotelianism within the faculty of arts, which was making steady inroads from philosophy into theology, were two controversies within the Parisian intelligentsia that prompted Bonaventure to deliver the conferences.5 The Hexaemeron records such tension: “For there have been attacks on the life of Christ by theo- logians in morals,6 and attacks on the doctrine of Christ by the false 1 Palémon Glorieux, “La date des Collationes de S. Bonaventure,” Archivum fran- ciscanum historicum 22 (1929), pp. 257–272, especially 270–272; Jacques Guy Bougerol, Introduction à Saint Bonaventure (Paris, 1988), pp. 237–238. 2 Unless noted, all citations of the Hexaemeron are from S. Bonaventurae opera omnia, vol. 5, ed. Collegii a S. Bonaventura (Quaracchi, 1889), pp. 327–454, hereafter Hex. 3 Olga Weijers, Terminologie des universités au XIIIe siècle, (Lessico Intellettuale Europeo) 39 (Rome, 1987), pp. 374–375, identifies the Hexaemeron as belonging to the genre of university sermon on a specific theme. Moreover, when a non-regent master delivered the sermons, as is the case with Bonaventure, the collatio resembles a con- ference rather than an official university act of the studia generalia. -

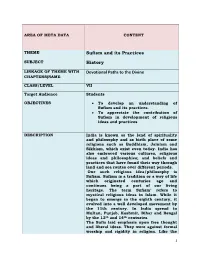

Sufism and Its Practices History Devotional Paths to the Divine

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME Sufism and its Practices SUBJECT History LINKAGE OF THEME WITH Devotional Paths to the Divine CHAPTERS(NAME CLASS/LEVEL VII Target Audience Students OBJECTIVES To develop an understanding of Sufism and its practices. To appreciate the contribution of Sufism in development of religious ideas and practices DESCRIPTION India is known as the land of spirituality and philosophy and as birth place of some religions such as Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, which exist even today. India has also embraced various cultures, religious ideas and philosophies; and beliefs and practices that have found their way through land and sea routes over different periods. One such religious idea/philosophy is Sufism. Sufism is a tradition or a way of life which originated centuries ago and continues being a part of our living heritage. The term Sufism’ refers to mystical religious ideas in Islam. While it began to emerge in the eighth century, it evolved into a well developed movement by the 11th century. In India spread to Multan, Punjab, Kashmir, Bihar and Bengal by the 13th and 14th centuries. The Sufis laid emphasis upon free thought and liberal ideas. They were against formal worship and rigidity in religion. Like the 1 Bhakti saints, the Sufis too interpreted religion as ‘love of god’ and service of humanity. Sufis believe that there is only one God and that all people are the children of God. They also believe that to love one’s fellow men is to love God and that different religions are different ways to reach God. -

Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure

The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Davis, Robert. 2012. The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9385627 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Robert Glenn Davis All rights reserved. iii Amy Hollywood Robert Glenn Davis The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure Abstract The image of love as a burning flame is so widespread in the history of Christian literature as to appear inevitable. But as this dissertation explores, the association of amor with fire played a precise and wide-ranging role in Bonaventure’s understanding of the soul’s motive power--its capacity to love and be united with God, especially as that capacity was demonstrated in an exemplary way through the spiritual ascent and death of St. Francis. In drawing out this association, Bonaventure develops a theory of the soul and its capacity for transformation in union with God that gives specificity to the Christian desire for self-abandonment in God and the annihilation of the soul in union with God. Though Bonaventure does not use the language of the soul coming to nothing, he describes a state of ecstasy or excessus mentis that is possible in this life, but which constitutes the death and transformation of the soul in union with God. -

Ignatian and Hesychast Spirituality: Praying Together

St Vladimir’s Th eological Quarterly 59:1 (2015) 43–53 Ignatian and Hesychast Spirituality: Praying Together Tim Noble Some time aft er his work with St Makarios of Corinth (1731–1805) on the compilation of the Philokalia,1 St Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain (1748–1809) worked on a translation of an expanded version of the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius Loyola.2 Metropolitan Kallistos Ware has plausibly suggested that the translation may have been motivated by Nikodimos’ intuition that there was something else needed to complement the hesychast tradition, even if only for those whose spiritual mastery was insuffi cient to deal with its demands.3 My interest in this article is to look at the encounters between the hesychast and Ignatian traditions. Clearly, when Nikodimos read Pinamonti’s version of Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises, he found in it something that was reconcilable with his own hesychast practice. What are these elements of agreement and how can two apparently quite distinct traditions be placed side by side? I begin my response with a brief introduction to the two traditions. I will also suggest that spiritual traditions off er the chance for experience to meet experience. Moreover, this experience is in principle available to all, though in practice the benefi ciaries will always be relatively few in number. I then look in more detail at some features of the hesychast 1 See Kallistos Ware, “St Nikodimos and the Philokalia,” in Brock Bingaman & Bradley Nassif (eds.), Th e Philokalia: A Classic Text of Orthodox Spirituality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 9–35, at 15. -

The Heights of Prayer: Contemplation My Soul Yearns for Thee in the Night, My Spirit Within Me Earnestly Seeks Thee

The Heights of Prayer: Contemplation My soul yearns for thee in the night, my spirit within me earnestly seeks thee. ~ Isaiah 26:9 ONTEMPLATION is the ultimate form of Chris- tor: “I look at him and he looks at me” (CCC 2715). tian prayer. The problem with describing Human words are useless in this total absorption in contemplation is that it is something beyond God; the soul listens to the Word of God. Cthe ability of words to convey. In a sense, it is In this highest form of prayer, God is the initia- a mystery or, perhaps, more accurately it can be de- tor. Contemplation is a gift from God that cannot scribed as mystical. The two be sought. This experience most notable writers of the is a grace, a gift that requires experience of contemplation deep humility and a willing are St. Teresa of Ávila and self-surrender to a covenant St. John of the Cross, con- relationship with God, a com- temporaries who knew each munion in which God takes other well and who worked the initiative to create his im- collaboratively to reform the age and likeness in the soul. Carmelite religious order in The contemplative yearns to Spain in the sixteenth centu- be obedient to his will, to be ry. Their works are a great a child of God, to imitate the treasure of the Church. St. humble obedience of Jesus Teresa, who was frequent- (see Phil 2:8) and the “let it ly favored with contempla- be to me according to your word” tive experience, explained it (Lk 1:38) of Mary at the An- as “nothing else than a close nunciation. -

Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan

Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan By Zainub Beg A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, K’jipuktuk/Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Theology and Religious Studies. December 2020, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright Zainub Beg, 2020 Approved: Dr. Syed Adnan Hussain Supervisor Approved: Dr. Reem Meshal Examiner Approved: Dr. Sailaja Krishnamurti Reader Date: December 21, 2020 1 Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan by Zainub Beg Abstract Abida Parveen, often referred to as the Queen of Sufi music, is one of the only female qawwals in a male-dominated genre. This thesis will explore her performances for Coke Studio Pakistan through the lens of gender theory. I seek to examine Parveen’s blurring of gender, Sufism’s disruptive nature, and how Coke Studio plays into the two. I think through the categories of Islam, Sufism, Pakistan, and their relationship to each other to lead into my analysis on Parveen’s disruption in each category. I argue that Parveen holds a unique position in Pakistan and Sufism that cannot be explained in binary terms. December 21, 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 3 Chapter One: Introduction .................................................................................. -

An Introduction to Christian Mysticism Initiation Into the Monastic Tradition 3 Monastic Wisdom Series

monastic wisdom series: number thirteen Thomas Merton An Introduction to Christian Mysticism Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 3 monastic wisdom series Patrick Hart, ocso, General Editor Advisory Board Michael Casey, ocso Terrence Kardong, osb Lawrence S. Cunningham Kathleen Norris Bonnie Thurston Miriam Pollard, ocso MW1 Cassian and the Fathers: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition Thomas Merton, OCSO MW2 Secret of the Heart: Spiritual Being Jean-Marie Howe, OCSO MW3 Inside the Psalms: Reflections for Novices Maureen F. McCabe, OCSO MW4 Thomas Merton: Prophet of Renewal John Eudes Bamberger, OCSO MW5 Centered on Christ: A Guide to Monastic Profession Augustine Roberts, OCSO MW6 Passing from Self to God: A Cistercian Retreat Robert Thomas, OCSO MW7 Dom Gabriel Sortais: An Amazing Abbot in Turbulent Times Guy Oury, OSB MW8 A Monastic Vision for the 21st Century: Where Do We Go from Here? Patrick Hart, OCSO, editor MW9 Pre-Benedictine Monasticism: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 2 Thomas Merton, OCSO MW10 Charles Dumont Monk-Poet: A Spiritual Biography Elizabeth Connor, OCSO MW11 The Way of Humility André Louf, OCSO MW12 Four Ways of Holiness for the Universal Church: Drawn from the Monastic Tradition Francis Kline, OCSO MW13 An Introduction to Christian Mysticism: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 3 Thomas Merton, OCSO monastic wisdom series: number thirteen An Introduction to Christian Mysticism Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 3 by Thomas Merton Edited with an Introduction by Patrick F. O’Connell Preface by Lawrence S. Cunningham CISTERCIAN PUblications Kalamazoo, Michigan © The Merton Legacy Trust, 2008 All rights reserved Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices The Institute of Cistercian Studies Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan 49008-5415 [email protected] The work of Cistercian Publications is made possible in part by support from Western Michigan University to The Institute of Cistercian Studies.