Decolonising Research & Curatorial Practice In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel INTRODUCING GREECE Edited by Francis King by INTRODUCING SPAIN Joan Comay by Cedric Salter INTRODUCING YUGOSLAVIA with a Foreword by by Lovett F

l In this series INTRODUCING INTRODUCING AMERICA by Barbara Kreutz and Ellen Fleming INTRODUCING GERMANY by Michael Winch Israel INTRODUCING GREECE edited by Francis King by INTRODUCING SPAIN Joan Comay by Cedric Salter INTRODUCING YUGOSLAVIA With a foreword by by Lovett F. Edwards David Ben-Gurion METHUEN & CO LTD 11 New Fetter Lane, London, E.C.4 .....,...... a.. - ... -.. x... mao·--z .. ,1.. .,..,- ..a-··""s"'' ..' -·-----.- ..... ~~-~ ... _.... .......... ___, .... ..._, ...... ~.- .. ,.... ,. _ First published in the U.S.A. with the title Everyone's Guide to Israel First published in Great Britain 1963 Copyright© 1962 Joan Comay Second Revised Edition 1969 Copyright © 1969 Joan Comay To Michael Printed in Great Britain by Cox & Wyman Ltd, Fakenham, Norfolk SBN 416 26300 3 (hardback edition) SBN 416 12500 x (paperback edition) This book is available in both hardback and paperback binding. The paperback edition is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated with out the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. INTRODUCING ISRAEL the vaulted roof is a fine example of Crusader architecture. Part of a hexagonal chapel stands near the original landing stage. This was one of three chapels attached to a large round church similar to the mother church of the Order in J eru salem. When the English Bishop Pococke visited the area in CHAPTER ELEVEN the eighteenth century, church and chapels, though ruined, were still standing, and in his travel account he wrote of the Haifa ' .. -

Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities

Original Scientific Articles Medical Education Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities Jehu E. Iputo, MBChB, PhD ABSTRACT Outcomes To date, 745 doctors (72% black Africans) have graduated Introduction The South African health system has disturbing in- from the program, and 511 students (83% black Africans) are currently equalities, namely few black doctors, a wide divide between urban enrolled. After the PBL/CBE curriculum was adopted, the attrition rate and rural sectors, and also between private and public services. Most for black students dropped from 23% to <10%. The progression rate medical training programs in the country consider only applicants with rose from 67% to >80%, and the proportion of students graduating higher-grade preparation in mathematics and physical science, while within the minimum period rose from 55% to >70%. Many graduates most secondary schools in black communities have limited capacity are still completing internships or post-graduate training, but prelimi- to teach these subjects and offer them at standard grade level. The nary research shows that 36% percent of graduates practice in small Faculty of Health Sciences at Walter Sisulu University (WSU) was towns and rural settings. Further research is underway to evaluate established in 1985 to help address these inequities and to produce the impact of their training on health services in rural Eastern Cape physicians capable of providing quality health care in rural South Af- Province and elsewhere in South Africa. rican communities. Conclusions The WSU program increased access to medical edu- Intervention Access to the physician training program was broad- cation for black students who lacked opportunities to take advanced ened by admitting students who obtained at least Grade C (60%) in math and science courses prior to enrolling in medical school. -

Arts Education in Israel

March 2018 ARTS AS A DRIVER FOR SOCIAL CHANGE IN ISRAEL Author : Dr. Diti Ronen Editor: Ariel Adiram Translation: Kim Weiss ART AS A DRIVER FOR SOCIAL CHANGE IN ISRAEL ART AS A DRIVER FOR SOCIAL CHANGE IN ISRAEL The guide that you are about to read examines the basic and profound question: can and how should the arts serve as a driver for social change.* Author: Dr. Diti Ronen For many, the arts are perceived as superfluous. A play thing for the rich. The Editor: Ariel Adiram crème de la crème that only be enjoyed by society’s elite. For many donors, it Translator: Kim Weiss makes more sense to donate to a women’s shelter, to building a new hospital or to a program that integrates children with disabilities into the regular school Graphic Design: Studio Keren & Golan system. This saves or improves lives in a direct way and produces tangible results. This guide was written with generous support from five partners: This guide shows that the arts are a sophisticated, substantive, innovative and Angelica Berrie, Russell Berrie Foundation ancient vehicle for social change. It illustrates, for the reader, the capacity of the Wendy Fisher, Kirsh Family Foundation arts to simultaneously influence an individual’s or society’s mind and soul. It also Irith Rappaport, Bruce and Ruth Rappaport Foundation presents the arts almost limitless creative capacity to effect positive change. Rivka Saker, Zucker Foundation Lynn Schusterman, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation This guide deals with core issues that are important for donors who donate to the arts: The writing of the guide was completed in consultation with an advisory committee: - How can philanthropic investment in the arts advance substantive and Tzion Abraham Hazan meaningful social change? Naomi Bloch Fortis - How can the impact of this type of investment be measured through genre- Prof. -

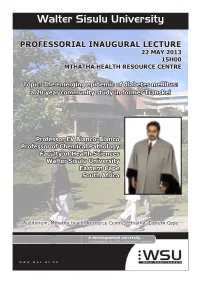

Walter Sisulu University

Walter Sisulu University PROFESSORIAL INAUGURAL LECTURE 22 MAY 2013 15H00 MTHATHA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE Topic: The emerging epidemic of diabetes mellitus: a 20 year community study in former Transkei Professor EV Blanco-Blanco Professor of Chemical Pathology Faculty of Health Sciences Walter Sisulu University Eastern Cape South Africa Auditorium, Mthatha Health Resource Centre, Mthatha, Eastern Cape www.wsu.ac.za WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY (WSU) DEPARTMENT OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES TOPIC “THE EMERGING EPIDEMIC OF DIABETES MELLITUS: A 20-YEAR COMMUNITY STUDY IN THE FORMER TRANSKEI” BY ERNESTO V. BLANCO-BLANCO PROFESSOR OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY DATE: 22 MAY 2013 VENUE: UMTATA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE 3 4 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION DIABETES MELLITUS Definition Historical background CLASSIFICATION OF DIABETES MELLITUS DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES MELLITUS RISK FACTORS AND PREDISPOSING CONDITIONS FOR DIABETES COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE GLOBAL PREVALENCE & GLOBAL BURDEN OF DIABETES THE AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE SOUTH AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS CONSEQUENCES OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES IMPLICATIONS OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES FOR HEALTH PLANNING DIABETES PREVENTION AS STRATEGY CONTROL OF THE CURRENT BURDEN OF DIABETES CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES 5 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION Chemical Pathology, Diabetes Mellitus and the Former Transkei I am a Chemical Pathologist by training. The term ‘pathology’ derives from the Greek words “pathos” meaning “disease” and “logos” meaning “a treatise”. Pathology is a major field of Medicine that deals with the essential nature of diseases, their processes and consequences. A medical doctor that specializes in pathology is known as ‘a pathologist’. Chemical Pathology is that branch of Pathology, which deals specially with the biochemical basis of diseases and the use of biochemical tests carried out at hospital laboratories on the blood and other body fluids to provide support to clinicians. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

The Conference Booklet

Contents Welcome and acknowledgements ............................................................................... 2 Keynote speaker information ....................................................................................... 5 Conference programme .............................................................................................. 8 Sunday 9th July ........................................................................................................ 8 Monday 10th July ..................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday 11th July .................................................................................................. 14 Wednesday 12th July .............................................................................................. 19 Abstracts ................................................................................................................... 23 The conference is generously supported by • The School of Divinity, University of Edinburgh • The British Association for Jewish Studies • The European Association for Jewish Studies • The Astaire Seminar Series in Jewish Studies, University of Edinburgh Other sponsors • Berghahn • Brill Publishers • Eurospan • Littman Library of Jewish Civilization / Liverpool University Press • Oxbow Books • Peter Lang • University of Wales Press • Vernon Press Connecting to WiFi during the conference Follow the instructions provided in your conference pack or use eduroam. Tweet about the conference #BAJS2017 -

Walter Sisulu University General Prospectus 2020

WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY GENERAL PROSPECTUS 2020 General Rules and Regulations www.wsu.ac.za GENERAL PROSPECTUS 2020 This General Prospectus applies to all four campuses of Walter Sisulu University. LEGAL RULES 1. The University may in each year amend its rules. 2. The rules, including the amended rules, are indicated in the 2020 Prospectus. 3. The rules indicated in the 2020 Prospectus will apply to each student registered at Walter Sisulu University for 2020. 4. These rules will apply to each student, notwithstanding whether the student had first registered at the University prior to 2020. 5. When a student registers in 2020, the student accepts to be bound by the rules indicated in the 2020 prospectus. 6. The University may amend its rules after the General Prospectus has been printed. Should the University amend its rules during 2020, the amended rules will be communicated to students. Students will be bound by such amended rules. CAMPUSES & FACULTIES MTHATHA CAMPUS 1. Faculty of Commerce & Administration 2. Faculty of Educational Sciences 3. Faculty of Health Sciences 4. Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences & Law 5. Faculty of Natural Sciences BUTTERWORTH CAMPUS 1. Faculty of Education 2. Faculty of Engineering & Technology 3. Faculty of Management Sciences BUFFALO CITY CAMPUS 1. Faculty of Business Sciences 2. Faculty of Science, Engineering & Technology QUEENSTOWN CAMPUS 1. Faculty of Economics & Information Technology Systems 2. Faculty of Education & School Development 1 2020 PROSPECTUS ALL CORRESPONDENCE TO BE ADDRESSED TO: -

The Higher Education Landscape Under Apartheid

CHAPTER 2 IAN BUNTING THE HIGHER EDUCATION LANDSCAPE UNDER APARTHEID This chapter lays out the South African higher education landscape as it was shaped by the apartheid policies of the National Party government prior to 1994. It describes how the disenfranchisement of the African majority culminated in the establishment of five separate legislative and geographic entities (the Republic of South Africa and four ‘independent republics’) and traces the process by which this policy led to the establishment of 36 higher education institutions controlled by eight different government departments. The chapter also describes the apartheid thinking which led to the differentiation of higher education in South Africa into two distinct types – universities and technikons – and shows how sharp racial divisions, as well as language and culture, skewed the profiles of the institutions in each category. 1. POLICIES OF THE APARTHEID GOVERNMENT 1.1. Racial divisions in South Africa At the beginning of 1994, South Africa’s higher education system was fragmented and unco-ordinated. This was primarily the result of the white apartheid government’s conception of race and the politics of race, which had shaped the higher education policy framework that it laid down during the 1980s. The apartheid government, under the influence of the ruling National Party, had, by the beginning of the 1980s, divided South Africa into five entities: · The Republic of Transkei (formed from part of the old Cape Province). · The Republic of Bophuthatswana (formed from part of the old Transvaal Province). · The Republic of Venda (also formed from part of the old Transvaal Province). · The Republic of Ciskei (formed from another part of the old Cape Province). -

Human Life in Early Bronze Age I Jericho a Study of the Fragmented Human Skeletal Remains from Tomb A61

Human Life in Early Bronze Age I Jericho A Study of the Fragmented Human Skeletal Remains from Tomb A61 Amanda Duell-Ferguson University of Sydney 2017 Abstract This Honours research thesis takes an in-depth look at the human skeletal remains from an Early Bronze Age I Jericho tomb, excavated by Kathleen Kenyon in the 1950’s. Tomb A61 contains highly fragmented and commingled human bones, and has remained unstudied until this year. A sample of the tomb has been analysed in order to study the demographics and health of the occupants. In doing so, it is not only the intention to create a picture of human life in Jericho at this time, but also tie the human skeletal remains back into the archaeology of Jericho, and the Southern Levant. The Southern Levant in the Early Bronze Age I is a region undergoing socio- economic transition. The non-urban Chalcolithic period makes way for the fortified and walled settlements of the Early Bronze Age II. The impact of this transition on the populations of the Early Bronze Age I is so far understood from the archaeology of the architecture and artefacts from settlements and corresponding funerary structures. Yet there is little study of the human remains themselves, and the stories they can tell about the populations of the Early Bronze Age Southern Levant. This lack of study is just a branch of a greater problem, however, which is the little uniformity across the study of human remains on an international level. Issues include varying global approaches to ancient human remains in the 19th and 20th Centuries, as well as the compromised state of fragmented and commingled human remains. -

Ceramic Artist

Hanna Itzhaki “אני החומר” Ceramic Artist חנה יצחקי קרמיקאית "אני החומר" חנה יצחקי - קרמיקה Hanna Itzhaki - Ceramics “אני החומר” חנה יצחקי קרמיקאית מבוא: גדעון עפרת צילום: אברהם חי עליזה אורבך דני זריהן נורית דגאי שגיא בן-יצחק “אני החומר” גרפיקה: חנה יצחקי עיבודי תמונה - דורית אמיר עיצוב, עריכה גראפית וקדם דפוס - אילאיל סיטון קרמיקאית עריכה תוכנית: גינת בסוק-יצחקי אילאיל סיטון עריכה לשונית: עידו בסוק חבירה ביד ובחרס גדעון עפרת 5 תרגום לאנגלית: שרון אסף חנה יצחקי - חיים ויצירה גינת בסוק-יצחקי 7 אמנות הווי מן תמונות שימושית חנוכיות ומסורת הטבע קרמיות © כל הזכויות שמורות ינואר 2008 95 71 53 43 21 אילאיל הפקות, תל-אביב 03-6243207 3 חבירה ביד ובחרס גדעון עפרת היה זה בקיץ של שנת 1951, עת נסעה חנה יצחקי קיצונית, היא דרשה לשמור על האופי של החומר, רעיון האמן בשירות הקהילה היה מובן לה מאליו, מקיבוץ אפיקים לירושלים, ובמשך שישה שבועות על הצבע הטבעי שלו”. חנה לא תחמיר, ובעבודות בין כחברת קיבוץ ובין כמי שהאמינה בכל מאודה למדה שם בקורס לקרמיקה אצל הדוויג גרוסמן. הקרמיקה שלה תאמר “הן” לגלזורה, אף כי תעשה באידאה של האמנות העממית. ב1957- פרסמה חנה הייתה אז בת 31, זה קרוב לשנתיים חברת זאת באיפוק. בה-בעת הקפידה על כריית החימר בעיתון הקיבוץ רשימה בשם “אמנות עממית”, ובה קיבוץ ומאז 1945 בישראל. למורה הייקית לציור לא עם תלמידיה באדמת עמק-הירדן ולא חדלה ניסחה תשתית רעיונית ליצירה קיבוצית אותנטית. היה ניסיון קודם במלאכת הקרמיקה, ואותו קורס לחנך לקשר חי בין היוצר לחומר. ברוח “גרוסמנית” במאמרה קראה ליצירה קיבוצית עממית בתחומי ראשון מסוגו מטעם מחלקת החינוך של המדינה דחתה את התעשייה החרושתית-ההמונית של מתכת, אריגה, קליעת סלים, רקמה, קרמיקה ועוד, הצעירה שינה את חייה. -

05/30/2015 in Tel Aviv / Israel ְס ִמיכּות JUXTAPOSITION

JUXTAPOSITION ְס ִמיכּות Exhibition from 03/01/2015 - 03/29/2015 in Hilden / Germany 04/30/2015 - 05/30/2015 in Tel Aviv / Israel ְס ִמיכּות JUXTAPOSITION Contents: Prolog Page 2 Participating Artists Page 4 Shira Tabachnik Page 5 - 6 Michael Igudin Page 7 - 8 Naamah Berkovitz Page 9 - 10 Gali Grinshpan Page 11 - 12 Oscar Abosh Page 13 - 14 Yifat Giladi Page 15 - 16 Reut Asimini Page 17 - 18 Karin Dörre Page 19 - 20 Wilfred H.G. Neuse Page 21 - 22 Katharina Gun Oehlert Page 23 - 24 Ulrike Siebel Page 25 - 26 Location Page 27 Kunstraum im Gewerbepark-Süd Location Page 28 Hanina Contemporary Art Imprint Page 29 Epilog Page 30 1 ְס ִמיכּות JUXTAPOSITION The exhibition "juXtaposition" presents This exhibition was created in honor of a week contemporary art, as an encounter of artists of Jewish culture in Germany, which marks 50 of BBK Dusseldorf and artists of Hanina Gallery years of diplomatic relations between Israel Tel Aviv. It is part of the Festival of Jewish and and Germany. Israeli Culture in the Rhineland 2015. In its honor, a collective of artists from Israel The title "juXtaposition" is derived from the and a group of artists from Germany, term juxtaposition (from lat. Iuxta "close to collaborated to create a joint exhibition. it", "next door" and positio "position", "position") meaning a close vicinity. It is In curating a joint exhibition within both Israel important in this terminology that both and Germany, one cannot avoid objects, places, subject matters are closely acknowledging the historic baggage carried by connected , but -however near- are perfectly both the artists and the viewers. -

Ravit Lazer Born in Israel 1969 Education 2006-2009 M.A

Ravit Lazer Born in Israel 1969 Education 2006-2009 M.A , Interdisciplinary program in the Arts, Tel Aviv University, Israel 1994-1995 B.F.A., Ceramic Art and Design, SUNY, NYC, USA 1994 Ceramic Design, Parsons School of Design, NYC, USA 1991-1993 Ceramic Art and Design Dept., Bezalel Academy, Jerusalem, Israel Teaching 2015-present Diploma Studies program, Benyamini School for Ceramic Art, Benyamini Center for Contemporary Ceramic. 2015-2017 Lecturer for Ceramic Design at the Interior design dep., Shenkar College, Ramat Gan 2014 Go Global, joint project with the Royal College, London and Shenkar College, Ramat Gan 2013- Present Lecturer at Benyamini School of Ceramic Art, Benyamini Center for Ceramic Art, Tel Aviv 2009- Present Lecturer at the Industrial design Dep. Shenkar College, Ramat Gan 2000- Present Ceramic design, sculpting and Pottery, Independent Studio, Modi'in 1997-1999 Ceramic Dept., Craft Student League, NYC, USA 1994-1997 Central Queens YMCA, Forest Hills, NY, USA Public Activities 2010 – Present Board member and director of the School of Ceramic Art and the Diploma Studies Program, Benyamini Center for contemporary ceramics, Tel Aviv 2007-2009 Board member, Shoeva Gallery, Shoeva 2001- 2009 "1280c - Ceramic Art Review", Writer, Member of Editorial Staff Curator 2017 Home Made, The School is out to the Galley, Benyamini Center, Tel Aviv 2013 SHIFT, Ceramic in Universities and Colleges of Art and Design in Israel, (Collaborating curator Shlomit Bauman), Benyamini Center, Tel Aviv. 2012 Proof Firing, Ceramic Design at the Product Design dep., Shenkar College, Ramat Gan Professional conference 2008 Restriction in freedom of Movement, Palestinians, Israelis and German artists, Ramallah, Tel Aviv, Umm el Phaem, Collaboration of Goethe institute and Um el Phaem Gallery.